On the Trail of a Greek Bourgeoisie Clad in Traditional Garb

Posted: July 1, 2014 Filed under: Archival Research, Greek Folk Art, Greek Folklore, Modern Greek History, Modern Greek Literature, Women's Studies | Tags: Angeliki Hatzimichali, Angelos Sikelianos, Antonis Benakis, Argyro Paparrigopoulou, Benaki Museum, Delphic Festivals, Emile Lester, Eva Palmer Sikelianou, Maria Hatzanesti-Pesmazoglou, Queen Amalia, Queen Olga, Virginia Romanou 4 CommentsPosted by Vivian Florou

Vivian Florou here contributes to the Archivist’s Notebook an essay about high-society Greek women in the decades between the two world wars. The traditional festive costumes that they wore on their social outings defined the aspirations of their class. Florou explores this fashion trend within the intellectual context of the period and the so-called “Generation of the Thirties.” Vivian, who studied archaeology and cultural heritage management, co-edited with Natalia Vogeikoff-Brogan and Jack L. Davis, a collection of essays, entitled Carl W. Blegen: Personal and Archaeological Narratives (forthcoming later this year). In that volume she explores the social life of two American couples (Carl and Elizabeth Blegen, and Bert and Ida Hill) who lived in the neoclassical mansion that now houses the J. F. Costopoulos Foundation on 9 Ploutarchou street in Kolonaki, Athens.

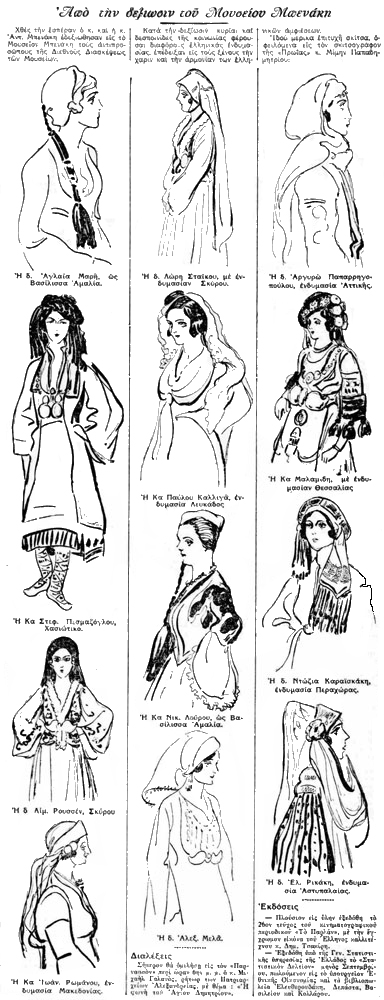

On Sunday evening, the 25th of October 1931, Antonis Benakis and his wife received representatives of the International Council of Museums in the grand ballrooms of the newly established Benaki Museum, his former residence. A page of the daily newspaper Πρωΐα (Proia) the next morning preserves forever in a caption to a sketch the particular event that distinguished that reception: “Κυρίαι και δεσποινίδες της κοινωνίας φέρουσαι διαφόρους ελληνικάς ενδυμασίας επέδειξαν εις τους ξένους την χάριν και την αρμονίαν των ελληνικών αμφιέσεων.” (Madames and mademoiselles of society in Greek costumes of various kinds demonstrated to foreigners the joy and harmony contained in Greek apparel.)

From their names on the sketch we learn that these were women of the Greek elite of that period. What were they doing dressed in clothes so foreign to the experiences of their daily lives? Why were they swirling the heavy fabrics of their garments amidst the foreign representatives? Did their behavior simply reflect a folkloric movement or was it an expression of “committed art” set against an historical backdrop? This clipping from Πρωΐα of 1931 inspired me to look for photographs that shed light on the appropriation of folk art by the Greek bourgeoisie in the interwar period (1919-1938), but also earlier, in the 19th century.

Sketch of women in traditional dresses at the gala in the Benaki Museum. “Πρωΐα” newspaper, October 26, 1931

After the foundation of the Greek state in the 1820s, the spirit of romantic nationalism that had earlier inundated the rest of Europe would prevail in Greece too and would bring with it a broader interest in the folk cultures of the newly constituted nation states. An example of behavior characteristic of this period was the formulation by the Greek Queen Amalia (1836-1862), and then by Queen Olga (1867-1913), of a conventional language of dress inspired by folk tradition, which would operate as a unifying symbol for their subjects and would visually inscribe in apparel the aspirations of the elite of that era (Macha-Bizoumi 2014, 48-55; Politou 2014, 56-63). For these reasons Queen Olga decreed a new attire for Ladies-in-Waiting at the Royal Court, one that was based on traditional garments of northern and eastern Attica.

Beyond these borrowed morphological elements, a recent study proves that in her creation of a new fashion for the Royal Court Queen Olga also adopted, with a faithfulness that is heartwarming, the materials and techniques of traditional Greek costumes. At a time when “European silks were available in all Greek urban centers […] Queen Olga was oriented toward traditional methods for the preparation of dresses for the Ladies-in-Waiting of her Court… what would have been a luxury for a rural Greek bride would suffice for her personal adornment and for her entourage” (Politou 2014, 63).

This tendency to appropriate traditional fashions would be enshrined at the turn of the 20th century in a more extensive and more coordinated shift toward popular culture; a search for the common man was one consequence of the nation’s desire to demonstrate that Greek culture was deeply rooted in the past. One should not forget that in those years the Greek nation-state was struggling to legitimize itself within an intensely competitive political environment. Thus for this purpose the first systematic initiatives to record popular culture were launched, projects such the Historical and Ethnographic Society (founded 1882), the Society for the Archaeology of Christianity (1884), the Greek Folklore Society (1908), the Lyceum of Greek Women (1911), and the Museum of Greek Handicrafts (1918). These institutions found support in a diverse mosaic of contemporary intellectuals, artists, and members of the bourgeoisie.

Hardly by chance, within this prevailing atmosphere the photographic studios of the day maintained in their ateliers at least one traditional festive Attic costume, embellished with typical τερζήδικα (braided) embroidery; the goal was to satisfy the yearnings of Athenian women of high society to be immortalized in traditional costumes as they were captured against a sacral-idyllic landscape worthy of their ancestors.

After the Asia Minor Disaster of 1922, Greece was cut off from roots that extended to Anatolia and at the same time it abandoned the “Μεγάλη Ιδέα” (the “Great Idea” that it should encompass within the nation state territories outside its borders that had belonged to the Byzantine Empire). Until then it had woven its political strategy around that ideology, as well as its social, educational, and cultural policies. Subsequently a new cohesive bond needed to be forged for the nation, one that would draw inspiration from various sources, but especially from the concept of “tradition.” “The new ‘Great Idea’ must create a living, unique, and productive modern Greek core, one that will continue the great tradition of Greece, will thrive in the modern age, will communicate simultaneously with West and East, and will irradiate with its works and ideas areas outside Greece’s national boundaries” (Theotokas 1961, 64).

The signal for “a return to roots” movement to begin had already been given (Hatzinikolaou 2003, 14). The folklorist Angeliki Hatzimichali, architects Aristotelis Zachos and Demetris Pikionis, and painters Fotis Kontoglou and Spyros Papaloukas, among others, had been arrayed in the first rank of the movement.

In its folk and Byzantine elements the house of the folklorist Angeliki Hatzimichali visually summarizes the atmosphere that prevailed at the time; her so-called Skyrian Corner promoted the remodelling of rooms throughout Greece according to a similar aesthetic. The persona of Hatzimichali provided a direct link between those intellectuals and members of the bourgeoisie who were enchanted by folk art, on the one hand, and scholars who were meticulously examining technological, folkloric, and anthropological aspects of traditional crafts, on the other (Meraklis 1999, 84). Hatzimichali’s “aura” inspired most initiatives of the ‘20s and ‘30s that were concerned with the interpretation of folk traditions, whether in publications, exhibitions, displays, or ancient revivals. The climax of this flood of activity was the organization by Angelos Sikelianos and Eva Palmer Sikelianou of the Delphic Festivals in 1927 and 1930. The Sikelianos couple tried to revive the Delphic Spirit that had promoted cultural and spiritual brotherhood among all peoples. With the archaeological site of Delphi as their stage, they organized performances of ancient dramas and exhibits of folk art and handicrafts.

Eva Palmer Sikelianos personally discussed with Angeliki Hatzimichali how folk art could provide a context for the Delphic enterprise and could encourage women of the urban elite to participate in it. She herself remarked: “Since I knew the variety and beauty of Greek handicrafts, just as I recognized the seriousness of Angeliki Hatzimichali’s study of the subject, I went to her for advice. She invited to her house those women of Athens who would be able to help in the organization of a representative exhibit of all arts in which craftspeople continued to excel, in mainland Greece, the Peloponnese, and the islands … this unique exhibit did fill all the houses of Delphi, each representing a district of Greece or an island” (Bournazakis 2008, pp. 297-298).

Delphic Celebrations 1930. Top row, third from left, Virginia Romanou, née Benaki, and bottom row, second seated from left, Argyro Paparrigopoulou. Photo by Nelly’s. Alexandros Romanos Archive.

The presence of these elite women at the Second Delphic Festival in May 1930 is perhaps also reflected in the purposeful way in which they pose in traditional costumes in front of Nelly’s lens in a very special anthology of artistic portraits (frontal, profile, and three-quarter views). Two of the women in the group sketched for Πρωΐα, Mrs. Romanou and Mrs. Paparrigopoulou, would pose by themselves, again in costume, before the lens of Nelly’s with the Delphic Rock behind them as an essential component of the shot.

Virginia Romanou at the Delphic Festival of 1930. The Delphic Rock is visible behind her. Photo by Nelly’s. Alexandros Romanos Archive.

The conscious participation of women of this social class in the Delphic Festivals, the most significant cultural events in Greece at that time, did not suppress a predisposition to be vain that was apparent in the period between the two world wars; such a tendency deeply influenced the era’s attitudes toward fashion. A host of Athenian society women who were immortalized in traditional dress by the photographic lens of Emile Lester thus indicate their “vanity” with a variety of “slightly different personal nuances” that emerge from the stance of the body, a seductive turn of the foot, the way in which they put their hands on their dress, or how they lower their gaze (Fotopoulos 1999, 6). [i] All photographic portraits of the era evoke a similar sensation.

Portrait of Maria Hatzanesti-Pesmazoglou in the traditional costume of Corfu. From the 1920s. Alekos Levidis Archive.

Athenian women and members of the bourgeoisie joined once more during the interwar period when they allied with a diverse group of collectors — Greeks who were living abroad and intellectuals —to create and staff the Benaki Museum, a world-class institution. That museum was founded on the 22nd of April in 1931 in an atmosphere already described, that embodied the spirit of “the return to roots” movement. Those who inspired that movement, women such as Angeliki Hatzimichali, Eva Sikelianou, and Eleni Eukleidi, would warmly support the museum from the start.

It was its founder, Antonis Benakis, who defined the seminal concept that lay behind the museum: the institution sought to reveal the face of Hellenism or rather the inner consistency that governs seemingly divergent external manifestations of Hellenism. In this way Hellenism’s historical trajectory would be documented.

An undated photograph that I selected by chance from the rich photographic archive of the Benaki Museum is not at all strange in this context. Antonis Benakis, in formal evening dress, is surrounded by women in traditional dress. This circle of women was immortalized in Hall 6, where already in 1931 the Benaki Museum’s renowned Coptic fabrics had been exhibited.[ii] Would some of these women have been present also at the reception Benakis convened to honor representatives of foreign museums in October of 1931?

Antonis Benakis surrounded by women in traditional dress in the Benaki Museum, probably from the 1930s. Benaki Museum.

Three of the women labeled in the Πρωΐα sketch (Romanou, Paparrigopoulou, and Hatzanesti-Pesmazoglou) have also been identified in photos presented here. They thus have acquired faces and bodies; and they almost speak to us in a language that attests to a class with aesthetic and ideological aspirations.

ENDNOTES

[i]Lester maintained a photographic studio on Panepistimiou St. from 1910 to 1935, Photographic archives with his work exist in the Benaki Museum, the National Historical Museum, and the Lyceum of Greek Women.

[ii]As did the women’s dresses these textiles demonstrated the unbroken continuity of Greek folk art through the ages. They are an important component of the Museum’s valuable collection.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I thank Alexander Romanos and Alekos Levidis for sharing with me documents from their family archive, Aimilia Yeroulanos and Nadia Macha-Bizoumi for providing me with information about the 1920s and 1930s, my colleague Dr. Spyros Moschonas for calling my attention to the clipping from Πρωΐα that inspired me to write this short note, and finally, Jack L. Davis and Natalia Vogeikoff-Brogan, who translated it from Greek to English.

REFERENCES

Bournazakis, K. 2008. Άγγελος Σικελιανός: γράμματα στην Εύα Πάλμερ Σικελιανού, Athens.

Fotopoulos, D. 1999. Το ένδυμα στην Αθήνα στο γύρισμα του 19ου αιώνα, Athens.

Hatzinikolaou, T. 2003. “Η στροφή στο λαϊκό πολιτισμό και τα πρώτα μουσεία,”Εισαγωγή στα εθνογραφικά 12-13, pp. 11-26.

Macha-Bizoumi, N. 2003. Το φωτογραφικό αρχείο του Αιμίλιου Λέστερ: Μια ‘φωτογραφική’ ερμηνευτική προσέγγιση στον τρόπο συγκρότησης της ιματιοθήκης του Λυκείου των Ελληνίδων στα πρώτα χρόνια λειτουργίας του, Ημερολόγιο του Λυκείου Ελληνίδων, Athens.

Macha-Bizoumi, N. 2014. “Φορεσιά ‘Αμαλία’: Το οπτικό σύμβολο της μετάβασης από το ανατολικό παρελθόν στη δυτική νεωτερικότητα,” in Αχνάρια μεγαλοπρέπειας: μια νέα ματιά στην παράδοση της ελληνικής γυναικείας φορεσιάς, Κατάλογος έκθεσης (4 Φεβρουαρίου – 2 Μαρτίου 2013), London, pp. 48-55.

Meraklis, M. 1999. “Η μελέτη του υλικού πολιτισμού: Μια όχι άσκοπη αναδρομή,” in Θέματα Λαογραφίας, Athens.

Politou, X. 2014. “Η ενδυμασία των κυριών επί των τιμών της βασίλισσας Όλγας: Αυλική κομψότητα με ντόπια υλικά,” in Αχνάρια μεγαλοπρέπειας: Μια νέα ματιά στην παράδοση της ελληνικής γυναικείας φορεσιάς, Κατάλογος έκθεσης (4 Φεβρουαρίου – 2 Μαρτίου 2013), London, pp. 56-63.

Theotokas, Y. 1961. Πνευματική πορεία, Athens.

Wonderful article. I am sharing a link to your article on my Hellenic Genealogy Geek blog – all my viewers will love it. Thank you. http://hellenicgenealogygeek.blogspot.com/

Thank you for a wonderful post. I only recently learned that Angeliki Hadjimihali’s father (Alexios Kolyvas) was the editor of the Proia newspaper. There is a series of drawings of well-known Athenians in traditional dress by Nicolas Sperling (have no idea who he was) in 1930. The originals are currently on view at the Hadjikyriakos-Ghikas Benaki museum. At some point, I think they were also made into stamps. Kostis Kourelis

Thank you for the very interesting bit of information that Hadjimichali’s father was the editor of Proia. Regarding Nicolas Sperling, please also note that he has illustrated two volumes edited by the Benaki Museum in 1948 and 1954 respectively, with the personal assistance of Antonis Benakis and texts written by Angeliki Hadjimichali. He depicts Athenian ladies and men dressed in traditional costumes. This is probably the last glance of this world, after the second world war… Vivian Florou

See acgart.gr for several dozen costume drawings by Sperling. (Russia. 1881-1940; active in Greece).