Disjecta Membra: The Personal Papers of Minnie Bunker

Posted: July 8, 2023 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Classics, History of Archaeology, Mediterranean Studies, Women's Studies | Tags: Agnes Baldwin, Chaironea Lion, Charles Weller, Constitution Square, Πλατεία Συντάγματος, Minnie Bunker, Nancy Perrin Weston 9 CommentsWe have been processing a large shipment of files that the Princeton office of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or School hereafter) mailed to Greece during their relocation in 2021. The files contain many surprises, especially those associated with the production of the School’s Newsletter. There we found a trove of unpublished (and unknown) photos and among other material an envelope with letters, calling cards, and photos that once belonged to Minnie Bunker (1867-1959).

Minnie was a high school teacher and a student at the School in 1900-1901 who returned in 1906-1907 and again in 1911-1912. She also is no stranger to the School’s Archives which already contained a small collection of her water-damaged photographs and letters, as well as an 1894 Baedeker, which her grandniece Nancy Perrin Weston (1922-2011) mailed to Athens in the 2000’s. After her aunt’s death in 1959, Nancy also spent time in Greece, working for renowned architect Constantine Doxiadis and volunteering in the School’s Library from 1963-1964. Minnie must have transmitted her love for Greece and the School to her grandniece because in 2011, the year of Nancy’s death, the School received $25,000 from her estate.

The thrill of archival research is not limited to discovery but encompasses rediscovery. The envelope that we found in 2020 contained another small cache of Minnie Bunker papers that Weston had shipped to the School’s office in New York in 1981, when the School was actively looking for letters and photos of past students and members on the occasion of its upcoming centenary.

Nancy responded to that call by mailing some of her great aunt’s papers together with a transcription of a long letter that Minnie had sent to her family on November 9, 1900. The letter together with accompanying photos was published in the School’s spring Newsletter of 1983 (p. 16). The rest of the material that Nancy had sent in 1981-1982 remained forgotten in a file cabinet, first in New York and later at Princeton, until the U.S. office’s recent relocation. Even now, as the Minnie Bunker papers are finally “reunited,” we know that they represent only a small fraction of the original collection. In 2002, after Nancy Weston had already sent to the School’s Archives a small number of items that once belonged to Minnie, she wrote me saying “I have a great many letters she [Minnie] wrote home from Greece and I hope to have time to read someday. Would you like them eventually?” To which I replied that “we should be most grateful if you ever decided to deposit the rest of your aunt’s correspondence to the American School.” In 2008, Nancy sent Charles Watkinson, then Director of ASCSA Publications, her aunt’s 1894 Baedeker, but no letters. Follow-up communication with the trustees of Nancy Perrin Weston’s estate in 2011 bore no results.

I am revisiting Minnie Bunker for two reasons. First, it is worth rereading her letter from 1900 published in the School’s Newsletter. Minnie wrote long and detailed letters because she wanted her family to follow her trips, “if you have a good map of Greece.” In pre-radio times, we can easily imagine families getting together to read loud a letter from far away, exotic Greece, with the visual aid of a map. And second, I wanted to grab the opportunity to publish two rare photos of Athens’ Constitution Square (Πλατεία Συντάγματος) from the early 1900s.

Minnie’s Boeotian Trip, 1900

As a high school teacher in Oakland, California, Minnie was not a typical student of the American School. Born in 1867 she was older than most of the other students in 1900-1901. After graduating from the University of California in 1889, one of six girls in her class, she lived most of her life in Oakland teaching at the local high school. She must have been introduced to the American School through either Edward B. Clapp, Professor of Classics at the University of California and member of the School’s Managing Committee (1894-1917), or Benjamin Ide Wheeler, who had just become President of the University of California. Wheeler was the School’s Annual Professor in 1895-1896.

On November 9, 1900, Minnie composed a long letter to her family describing blow-by-blow the School’s trip to Boeotia. Minnie was staying at the Grand Hotel on Mouson (Μουσών) Street (now Karageorgevich of Serbia), at the southwest side of Constitution Square (Syndagma Square). The other female students of the School stayed at the Merlin House on Kephissias avenue opposite the Palace (now the Hellenic Parliament). The School had a limited number of rooms, and those were reserved for its male students.

Of the thirteen people who participated in the trip, five travelled by horse carriage and the rest on bikes. They first rode west to see Eleusis and Salamis, and from there through a pass they entered the Boeotian plain. Although they were travelling on dirt roads, the pass allowed them to speed down with the carriage, “while the bicyclists had to coast with a watchful eye.” At the sign of the first bicyclist, villagers would come out to stare at the strangers. Minnie identified many of the people living in Boeotia as Albanians (Αρβανίτες) although they insisted on being called Greeks. The living conditions were quite primitive, humans and animals living side-by-side, chickens and turkeys flying by, and cats dividing “the spoils of the frying pan where the last meal had been cooked.” The food was cooked on a fire burning on the stone floor. No hearth (a note for archaeologists looking for kitchens in their household assemblages).

Of great interest is her comment about the numerous turkeys in the Greek countryside: “our way is often stopped by great bands of them being driven to market.” What happened to the Greek turkeys? Nowadays it is hard to find fresh turkeys in butcher shops with the exception of Christmas when the American Farm School in Thessaloniki is the main supplier. (The photo below comes from the papers of Agnes Baldwin, a well-known numismatist, who was also a student at the School in 1900 and part of the group. Agnes Baldwin Brett’s papers are deposited in the Archives of the American Numismatic Society.)

Minnie skips worrisome descriptions in her letter, such as the dirty, bug-infested pensions or the frequently stuck horse carriage. Not a hint of complaint or exasperation. Instead, she adopts a cheerful tone and turns everything into an adventure. It had to be so. When Bruni Ridgway donated to the ASCSA Archives her letters from when she was a student at the School in 1955-1956, she warned me about their cheerful tone. Because mail was slow and international calls prohibitively expensive, students did not want their parents to worry about them.

Two (or Three?) Boeotian Lions

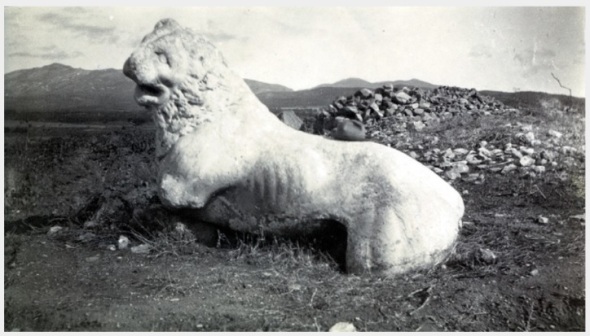

Minnie described in a sentimental way the fragments of the Lion of Chaironea that lay beside the road.

Some say that a leader in the Greek War [of Independence] maliciously broke it in pieces, others think that this ruin is only the result of time […]. At any rate, there he lies with his great head in the dust, broken, disregarded for centuries, like the nation whose defeat he marks; if, as is hoped, the Chaeronean lion should be restored and set up again, he would form a still more fitting emblem of the new Greece that is gathering itself from the shocks of the past.

So, Minnie and her group had seen the Chaironea lion just before its restoration which took place in 1902-1903. She also recorded what the locals were saying about its restoration: “the war [she refers to the Greek-Turkish war of 1897 which ended with Greece’s defeat] prevented its being done two years ago, but now -they shrug their shoulders and say ‘When? Greece is so poor!’” Although there is no photo of the Chaironea lion in Minnie’s papers, there is one preserved in the papers of her fellow student, Charles Weller, who would excavate the Vari Cave (Attica) in the spring of 1901.

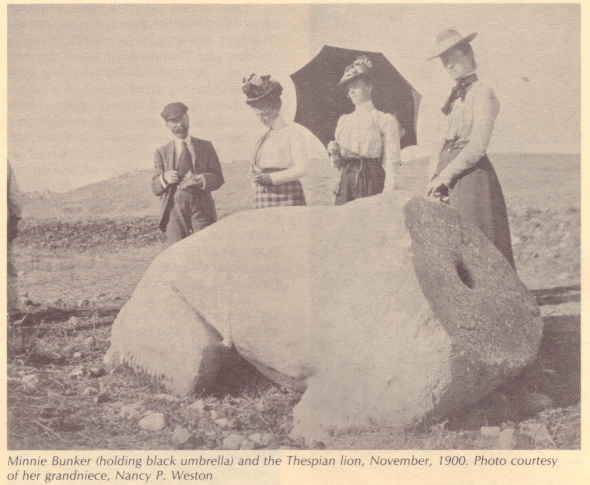

Minnie’s papers once preserved a photo depicting fragments of another Boeotian lion (not preserved in her papers at the School’s Archives). We do not know who took the snapshot, not Minnie who stands behind the lion holding a dark umbrella. The other people in the photo, left to right, are: Rufus B. Richardson, Agnes Baldwin, and an unidentified member of the group. She did not describe this one in her letter although Richardson, the School’s Director and leader of the trip, must have told the students that this other lion most likely belonged to a polyandrion (communal tomb), first excavated by Panayotis Stamatakis in 1882, and later, in 1911, by Antonios Keramopoulos. Keramopoulos connected the burials and the lion with the funeral monument (polyandrion) erected by the Thespians to honor their dead soldiers at the Battle of Delion in 424 B.C.

While going through the Baldwin photos which are available online at the site of the ANS, I also came across another lion with a puzzling provenance: Agios Nikolaos, Priniatikos Pyrgos, Crete. After publishing the post, John Camp and Brady Kiesling sent me notes identifying the lion as the one still to be found next to the church of Agios Nikolaos at Kantza in Attica. Baldwin must have scribbled Agios Nikolaos on the back of the photo, but the site was misidentified during cataloguing. I also remembered that the Kantza lion is mentioned in a travelogue by Lincoln and Margaret MacVeagh, Greek Journey (New York 1937) where Peggy, the daughter of Lincoln, wrote: “But my lion [the Kantza one] is nice and friendly, even if he isn’t beautiful. One of the nicest things about him is that Daddy can’t tell you anything about him, where he came from or why. I think he just grew here” (p. 265-267).

Furthermore, in 2012, the Greek police confiscated a marble lion at Itea, Phocis. It is very possible that the confiscated lion was originated from Boeotia before it was transferred to the harbor of Itea for illegal exportation. The newspaper mentioned that in 2009 the police had found in Boeotia another marble lion that weighed about 300 kilos, deserted by smugglers.

Πλατεία Συντάγματος (Constitution Square), ca. 1900

Minnie’s papers also contained two rare photos of Constitution Square. On the one that shows the south side of the Square, the unidentified photographer has chosen to focus on Hermes Street (Οδός Ερμού). (There are contemporary postcards with similar views, lacking, however, the clarity and quality of our photo). The corner building on the left is the Hotel Victoria. The corner building on the right is the Grand Hotel d’ Anglettere where Minnie stayed during her second time in Athens, in 1906-1907. (The third floor which was added in 1905 gives us a terminus post-quem for the date of the photo.) On the ground floor of the Grand Hotel d’ Angleterre, we see the office of Thomas Cook & Son, the famous travel agency. (There are so many references to Cook’s agency in the letters and diaries of the ASCSA members, but until I came across this photo, I did not know its exact location in Athens.) The arches between the lampposts were carrying the gaslight. On the south side of Hotel Victoria, at the corner of Hermes and Nike streets, one can discern the billboard of Boehringer’s photo shop. Carl Boehringer worked as a photographer in Athens in the late 19th/early 20th century. He held the unofficial title of the royal photographer because he had photographed members of the royal family (Xanthakis, A. 2008. Ιστορία της ελληνικής φωτογραφίας, 1839-1970, Athens, 173-174).

The other photo shows the southwest side of Constitution Square looking at Mouson Street (Οδός Μουσών, Karageorgevics of Serbia today) having taken its name from a boundary (horos) stone found nearby (ΟΡΟΣ ΚΗΠΟΥ ΜΟΥΣΩΝ). Minnie scribbled that she stayed at the “Hotel Grand Patrion[?]”in 1900-1901, the building adjacent to the Grand Hotel (an extension?). Built in 1844 and remodeled by Ernst Ziller in the early 20th century, the arched building housed in later years on its rooftop the workshop of famous painter Yannis Tsarouchis. The famous bookstore ΕΛΕΥΘΕΡΟΥΔΑΚΗΣ occupied the building’s ground floor. Later, when the arched building was demolished and Grand Hotel ended its operation, Eleftheroudakis moved into the ground floor of the old Grand Hotel at the corner of Mouson (Karageorgevics of Serbia) and Stadiou (https://repo.in-athens.gr/item/825). Looking at Stadiou Street to the right of the photo, one gets a glimpse of the royal stables, which were demolished in the 1930s to build the Μετοχικό Ταμείο Στρατού, an art deco building that houses today the ATTICA shopping mall.

(If you are interested in the history of the city of Athens, I recommend that you check out a new and useful site titled in-Athens: Ιστορίες μιας αόρατης πόλης. And if you are on Facebook, it is worth checking out the site Η ΑΘΗΝΑ ΜΕΣΑ ΣΤΟ ΧΡΟΝΟ, run by Despina Drepania).

Author’s Note

It is the 10th anniversary of From the Archivist’s Notebook. It all began in July 2013, when the ASCSA suspended for a short period the publication of its Newsletter where I used to write a short story once or twice a year. Κάθε εμπόδιο σε καλό we say in Greek. The launch of the blog gave me the opportunity not only to publish a story almost every month, but also to invite guest writers to contribute from their own research in archival repositories. (My first story was published on July 13, 2013, One Portrait, Three Institutions: Anders Zorn’s Portrait of William Amory Gardner.) Ten years later From the Archivist’s Notebook counts 125 stories, about 1,500-2,000 monthly hits, and a good number of fans. Many of the essays have featured in bibliographies of scholarly publications or have been included in academic syllabi. Not only did it become the main publicity vehicle of the School’s Archives, but it also facilitated contact with descendants of past ASCSA members, who now have a trusted repository to deposit papers and photos of their parents or grandparents. Most importantly, the readers of the blog have come to realize that the School’s Archives are an important research facility for interdisciplinary scholarship.

_____________________

The post was revised on July 10, 2023 with new information about the marble lion found near the church of Agios Nikolaos.

The Cretan Idyll of Harriet Boyd and Charles Henry Hawes

Posted: February 12, 2022 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Art History, Biography, Classics, Crete, Greek Folklore, History of Archaeology, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism, Women's Studies | Tags: Charles Henry Hawes, Crete, Harriet Ann Boyd 4 CommentsBY CURTIS RUNNELS – PRISCILLA MURRAY

Curtis Runnels, Professor of Archaeology at Boston University and an expert in Palaeolithic archaeology in Greece, and his wife Priscilla Murray, an anthropologist and Classical archaeologist, here contribute to From the Archivist’s Notebook a story about their purchase of a sketchbook from the early 20th century with watercolors depicting places and people on Crete.

We visited an antiquarian bookfair in Concord, New Hampshire, about twelve years ago and a booth belonging to a dealer from Vermont, who specialized in original artwork, caught our eye. Sorting through piles of miscellaneous materials, we found a few things relating to Greece, and a small (8 by 4 inches; 20 x 10 cm) artist’s sketchbook grabbed our attention. It was displayed on a table opened to a watercolor view that seemed familiar. Surely it was the entrance to the harbor at Herakleion on Crete! And indeed, penciled in one corner was the inscription “Candia,” the older name for the city which both confirmed the identification and provided a clue that the sketchbook, as dealers in antiques like to say, “had some age.” There were other artworks in the sketchbook that are dated to April 1905, and still others with various dates in 1915, and one dated to 1916. The artwork from 1905 was the most interesting for us. Turning the pages of the sketchbook we saw line drawings of dancers at Knossos and a man drawing water from a well in Siteia, pastels of houses labeled Knossos and “Sitia, as well as watercolors and line drawings of Mykonos, Ios, and other Cycladic islands, Sounion, and Athens. The unknown artist was interested particularly in the new Minoan finds from Knossos as is evident from the line drawings of wall paintings and artifacts in the “Candia Museum.”

Although there is no artist’s signature, we guessed that the artist must be someone interesting, perhaps even someone we would recognize. After all, how many Americans or British travelers (the fact that the titles are in English is the reason for assuming the nationality of the artist) were sufficiently interested in Knossos and the Minoans to visit Crete in 1905 at a time when there was much unrest on the island? We bought the sketchbook and took it home to do more research.

At Home with the Schliemanns: The “Iliou Melathron” as a Social Landmark

Posted: January 6, 2022 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Arts and Crafts Movement, Biography, History of Archaeology, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism, Women's Studies | Tags: Charles Wesley Bradley, Ernst Ziller, Heinrich Schliemann, Iliou Melathron, Sophia Schliemann 8 CommentsHeinrich Schliemann, the famous excavator of Troy, Mycenae, and other Homeric sites, was born in Germany on January 6, 1822–the Epiphany for western Europe and Christmas Day for other countries such as Imperial Russia and Greece which still used the Old (Julian) Calendar until the early 20th century. A compulsive traveler, Schliemann rarely returned to Athens before late December or early January, just in time to celebrate both his birthday and Christmas on January 6th.

From today and throughout 2022, many institutions in Europe, especially in Germany but also in Greece, will be commemorating the bicentennial anniversary of his birth. The Museum of Prehistory and Early History of the National Museums in Berlin is preparing a major exhibition titled Schliemann’s Worlds, which is scheduled to open in April 2022. Major German newspapers and TV channels are in the process of producing (or have already produced) lengthy articles and documentaries about Schliemann and his excavations at Troy in anticipation of the bicentennial anniversary, and Antike Welt has published a separate issue, edited by Leoni Hellmayr, with eleven essays about various aspects of Schliemann’s adventurous life.

The American School of Classical Studies at Athens, where Heinrich’s and Sophia’s papers have been housed since 1936, in addition to contributing to all the activities described above, will be launching an online exhibition, The Stuff of Legend: Heinrich Schliemann’s Life and Work, on February 3, 2022, showcasing material from the rich Schliemann archive.

The Transatlantic Voyage of a Greek Maiden

Posted: April 17, 2021 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Classics, History of Archaeology, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism, Women's Studies | Tags: Acropolis Kore 675, Gisela M. Richter, Greek Pavilion World Fair 1939, Henry Morgenthau, Hermes of Praxiteles, Spyridon Marinatos 7 CommentsOn March 31, 1947, Gisela Richter, Curator of Greek and Roman Art at the Metropolitan Museum of New York, sent a confidential letter to Carl W. Blegen, Professor of Classics at the University of Cincinnati and a distinguished archaeologist. Richter approached Blegen not only because they were friends but because, by having lived in Greece for many years, Blegen had formed strong connections with the local community at all levels. In addition, during World War II, Blegen had offered his services to the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and, upon his return to Greece, he had served as Cultural Attaché at the U.S. Embassy (1945-1946). Richter was writing Blegen about five pieces of Greek sculpture on loan to the Metropolitan Museum, including Kore 675 from the Acropolis. Richter refers to her as the “Maiden”.

“As I think I told you, we are naturally anxious to return to the Greeks what they have kindly lent us but very much hope that some arrangement can be made by which we may retain that one Maiden. The other pieces we are not even going to ask for, as there are obvious reasons in each case why the Greeks would not want to part with them, and asking for them would only weaken our case for the Maiden. The latter is one of many, and would hardly be missed in Athens, whereas here she would act as an ambassadress of goodwill, etc., etc.”

Richter sought Blegen’s advice about how to proceed with the request. “The loan to Greece ought to create goodwill for America, but naturally we don’t want to seem to cash in on it.” Richter was referring to President Truman’s announcement of March 1947, known as the Truman Doctrine, whereby the U.S. government granted $300 million in military and economic aid to Greece and $100 million to Turkey. “Would it be better to ask for the piece as a gift and perhaps compensate for it in some other way, or would a direct purchase be better? You who have been in Greece recently and know Greek politics will be able to advise us better than anyone else,” concluded Richter.

Blegen’s response exists only as a draft in his personal papers at the Archives of the American School of Classical Studies (ASCSA or School hereafter). The mention of [Spyros] Skouras’s name in his response (not mentioned in Richter’s letter) suggests that Richter might have followed up with a second letter or a telegram or a note to Blegen’s wife, Elizabeth. To Richter’s disappointment, Blegen could not think “of any altogether satisfactory way of approach to recommend” (ASCSA Archives, Carl W. Blegen Papers, Box 13, folder 1, April 6, 1947). However, he did not reject the idea of having Spyros Skouras, the Greek-American movie mogul, mediate with the Greek authorities “since he has much influence and could apply some pressure. If he could propose it in the right quarters as an idea of his own, not inspired by you, there might be some hope that he could persuade them to make the offer as a spontaneous gesture of friendship.” Blegen thought of another alternative as well: “to ask Bert [Hodge] Hill to try his powers of persuasion.” Hill, Director of the American School from 1906 until 1926, was still considered to be social capital by many at the School. A gifted individual with access to the upper echelons of a small Athenian society, including the royal family, Hill “had his way with men” and could influence politicians. Blegen thought that it would have to be a political decision since the Archaeological Service would likely oppose to it.

There is no other correspondence between Blegen and Richter on this matter. We know that the Acropolis Maiden and the other pieces of sculpture were returned to Greece, so one assumes that either Richter did not press the issue further or that the mediators were unsuccessful. However, it is interesting to read an announcement in the Greek newspaper ΕΛΕΥΘΕΡΙΑ on August 11, 1948, titled “The Greek State will Sell Certain Antiquities. Superfluous in Museums,” which implies that the Ministry of Education might have considered briefly the idea of selling duplicate antiquities, in order to finance the reopening of Greek museums and the beautification of those archaeological sites that had suffered much during the War.

Read the rest of this entry »A PORTRAIT OF A (PAGAN) LADY: MABEL GORDON DUNLAP

Posted: December 11, 2020 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Art History, Biography, History of Archaeology, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism, Serbia, Women's Studies | Tags: Ion Dragoumis, Mabel Dunlap Grouitch 4 CommentsIn 1897 a young American woman announced in the newspapers her return to Chicago after a year in Europe. “Miss Mabel Gordon Dunlap of Michigan Boulevard, who has been in Europe for a year, will sail for home on Wednesday” (Chicago Inter Ocean, August 15, 1897). The same woman had also made an earlier announcement that she was still in London “spending most of her time at the British Museum” (17 July 1897). While in London she printed a handsome pamphlet, titled “A Critical Study of Sculpture and Painting,” that contained information about her as a teacher and a lecturer, and a summary of two art courses that she was “ready to deliver before ladies’ clubs and schools” in the winter: “A Course of Twelve Lectures on the History & Philosophy of Greek Sculpture,” and “A Course of Twelve Lectures of the History of Painting in Italy.” While in England she had attended lectures by Charles Waldstein, Professor of Fine Arts at Cambridge University (and former Director of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens), whom she quoted in her brochure: “There are those who make art, there are those who enjoy art, and there are those who understand art.” Dunlap’s courses, fully illustrated with stereopticon views, were designed to help people understand art.