Mycenaean Mementos and the Govs: The Materiality of the Wace-Blegen Friendship

Posted: September 1, 2019 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, History of Archaeology, Philhellenism | Tags: Alan J. B. Wace, Émile Gilliéron, Carl W. Blegen, Kim Shelton, Rookwood Pottery Company 5 CommentsPosted by Jack L. Davis

Jack L. Davis, Carl W. Blegen Professor of Greek Archaeology at the University of Cincinnati and a former director of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (2007-2012), here writes the biography of three objects, modern copies of Mycenaean originals, which once belonged to Carl W. Blegen and Alan Wace, the “Govs” of Mycenaean archaeology. These objects were once woven in some way into the personal relationship of these two individuals who shaped the field of Mycenaean studies.

They will honor him in their heart as if he were a god

And send him to his dear homeland in a ship

With gifts of bronze, gold, and fabrics in such abundance

As Odysseus would never had taken from Troy

If he had arrived home unscathed with his share of booty.

(Od. 5.36-40)

Such is Zeus’s prediction of Odysseus’s fate among the Phaeacians. And guest gifts are a phenomenon not only well-known to Classicists, but a concept that has had an impact on anthropological thought for nearly a century — at least since the publication in L’Année Sociologique of Marcel Mauss’s “Essai sur la donne” in 1925 — and, through it, on the interpretation of patterning in archaeological data. Mauss demonstrated that in pre-modern exchange systems there were obligations to give and receive, but especially to reciprocate in the presentation of gifts, practices deeply embedded in social systems. In the field of archaeology, gift exchange has been seen, prominently since the 1970s, as a mechanism that accounts for distributions of material goods (e.g., T.K. Earle and J.E. Ericson eds., Exchange Systems in Prehistory, New York 1977), and studies of the cultural biographies of exchanged artifacts have been popular (A. Appadurai, The Social Life of Things, Cambridge 2013).

This post is not, however, concerned with archaeological finds, but rather with the histories of a few mementos owned by two of the most famous Greek prehistorians of the 20th century, Alan Wace and Carl Blegen, best friends and colleagues,“the Govs” as they called themselves (see Y. Fappas, “The ‘Govs’ of Mycenaean Archaeology: The Friendship and Collaboration of Carl W. Blegen and Alan J. B. Wace as Seen through Their Correspondence,” in J.L. Davis and N. Vogeikoff, eds., Carl W. Blegen: Personal and Archaeological Narratives, Atlanta 2015, pp. 63-84). The copies of Mycenaean artifacts that I consider here have sometimes been thought to have been material manifestations of their friendships, mutually reciprocated gifts. But were they really?

A Pair of Goblets

On the final day of my directorship of the ASCSA, June 30, 2012, Jim Wright, my successor, and I drank from a metal goblet of Early Mycenaean shape and style — high stem, shallow bowl with out-turned rim, dogs biting the rim, two strap handles. We were toasting the passing of the baton from one administration to the next. The goblet in question had been sitting on a table at the foot of the staircase leading to the piano nobile of the Director’s house during my entire tenure in Athens (2007-2012). I had heard through the grapevine that it was one of a pair that celebrated Wace and Blegen’s friendship, each man having one. That’s a wonderful story and one that I repeated to others on a number of occasions, but was it true?

Jack Davis and Jim Wright drinking out of Carl Blegen’s goblet, being watched by an approving Olga Palagia, June 30, 2012. Photo: Natalia Vogeikoff-Brogan.

This past spring I wrote Lisa [Elizabeth Bayard Wace] French to get her take on the matter, and she replied: “I am not sure whether the govs bought these replicas at the same time or not but I do well remember that I knew even as a child that each family had one. Attached is the photo of Ken Wardle filling the one held by Cynthia [Shelmerdine] with the bottle of wine brought by [one guest] … It was at a buffet dinner I gave at Millington Road … all the relevant Cambridge people came….“

Ken Wardle filling Wace’s goblet held by Cynthia Shelmerdine. Photo Elizabeth Wace French.

One of the gold goblets that Stamatakis found at Myceneae, now in the National Archaeological Museum. Photo: Jack L. Davis.

Where and when did the Govs get these goblets? Did they, in fact, buy them together? Were they gifts? Both are copies, of gold, not silver, goblets found by Panayiotis Stamatakis at Mycenae near the Schliemann grave circle (see H. Thomas, “The Acropolis Treasure from Mycenae,” Annual of the British School at Athens 39 [1938/1939] 65-87). Wace’s goblet, now in the hands of his granddaughter, Ann French, is water-marked English sterling manufactured in 1908, in Chester by the firm of Nathan and Hayes – before, that is, Wace and Blegen met for the first time. A discoloration on the base was likely created by a price tag, thus not made-to-order. The goblet is also labelled underneath: “Mycenaean 14th cent. B.C.” Nathan and Hayes manufactured and marketed a line of replicas.

Blegen’s goblet, in contrast, is unmarked and unlabeled — although nearly identical. It was not made by an English silversmith nor at the same time as Wace’s — nor is it silver, as we recently discovered through XRF analysis in the Wiener Laboratory of the ASCSA. It is instead a brass electrotype.

Carl Blegen’s copy of the gold goblets found at Mycenae near Grave Circle A. Photo: Natalia Vogeikoff-Brogan.

Dr. Dimitris Michailidis of the Wiener Laboratory analyzing Blegen’s goblet. Photo: Natalia Vogeikoff-Brogan.

Did Wace have it made for Blegen, perhaps in Greece? It is not impossible that it was acquired from the shop of the Émile Gilliérons, père and fils, on Skoufa St. in Kolonaki. (On the Gilliérons, see Sean Hemingway’s lecture at the Met in 2011; and Watercolors of the Acropolis: Émile Gilliéron in Athens: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, v.76, no. 4 [Spring, 2019]. The Met was one of the Gilliérons’ best customers.)

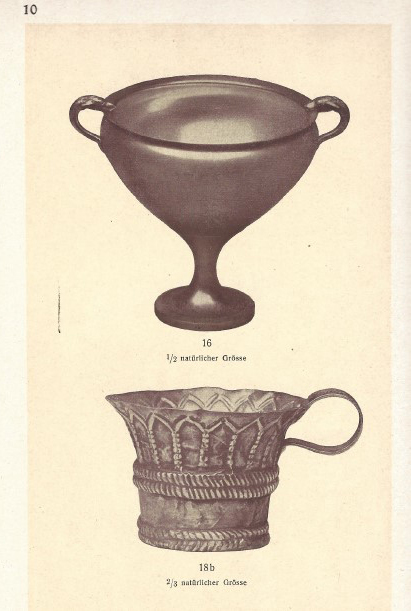

Certainly Wace and Blegen knew the Gilliérons. Gilliéron fils worked with Wace in 1923 at Mycenae, as did Blegen. He then worked for Blegen at Prosymna, and again, in the wake of the 1939 campaign, at the Palace of Nestor. In the archives of the Department of Classics at the University of Cincinnati we have a small notepad with pen and ink drawings of finds from Tholos Tomb III at Pylos, as well as casts of two ivories. But did the Gilliérons make the goblet? It is listed in their sale catalogue (Galvanoplastische Nachbildungen: Mykenischer und kretischer [minoischer] Altertümer, Athens, pl. 10, no. 16), but it was normal to hallmark their products with “Gilliéron Athènes” in an oval.

The gold Mycenaean goblet in the Gillieron catalogue.

A Mysterious Clay Alabaster

As I discovered more recently, the goblets are not the only Wace-Blegen realia enrobed in mystery. During the extraordinarily wet and cold winter of 2019 Shari Stocker and I were dining in Alameda, California, at the home of Kim Shelton and Dimitris Dimopoulos, her husband. Dimitris, who hails from the village of Ancient Mycenae, is a professional chef. Shari and I hung out in the kitchen, talking to Kim as Dimitris threw together a Mexican meal.

Kim’s LEGO models of a Starship Enterprise and a Millennium Falcon dominated conversation in their dining room, as did the biographies of her two cats. It was only late in the meal that I saw a familiar friend sitting on a small table by the front door – a vase made by Cincinnati’s Rookwood Pottery, the best known of all 20th century producers of American Art Pottery. Shari, who in an earlier life bought and sold art pottery, saw it too.

The date of the pot was clear –1924 (written XXIV) incised before firing on its base – but the shape was odd. It was a masterful reproduction of a Late Helladic II alabastron! We had never before seen a prehistoric Greek vase imitated by Rookwood, let alone in a “production piece,” a category intended for the mass market. Even Classical Greek shapes are rare (although Shari and I have a calyx crater in our own collection).

Copy of a Late Helladic II alabastron by Rookwood Pottery, 1924. Kim Shelton Collection. Photo: Jack L. Davis.

The alabastron turned out to have been a gift to Kim from Lisa French, one of a pair of alabastra inherited from her parents. (Lisa’s daughter Ann now has the other.)

Here was a real conundrum. Kim thought Lisa had told her that the vases were presents from Blegen, but, if they had been commissioned by Blegen as friendship tokens, why hadn’t each Gov kept one? How exactly had the Waces come to possess alabastra made in Cincinnati? Lisa suggested a possibility:

“The family story as I remember it is that my parents visited the factory and AJBW was asked to design a shape they could produce – which they did – My mother loved the black one and used it every year for a lovely low dish of anemones. This must have been on a visit to the US between their marriage in 1926 [1925] and my birth [1931] BUT I do not know if it was before or after CWB got there as a very great friend of my mother was Mrs Alice Reynolds sister to Mrs Timkin who lived in Cincinnati – They had served together at the YWCA canteen for returning soldiers in New York in 1918/19.”

There are some problems with this scenario, however. The Waces were not married until June of 1925 and the vases are dated to 1924. The idea that Blegen gave the alabastra to Wace is also not likely. Although by 1924 they had become fast friends, Wace having schooled him in Mycenaean pottery already in 1916 at Korakou, Blegen only came to the University of Cincinnati in 1927.

The Wace Family in the 1930s. ASCSA Archives, Carl W. Blegen Papers.

Lisa Wace with her godfather Carl Blegen, 1937. ASCSA Archives, Carl W. Blegen Papers.

Over the next few months I obsessively pursued the origin of the alabastra. First I wrote to Suzanne Perrault, an art pottery appraiser on Antiques Roadshow and a friend of ours. (Mary Darlington of the ASCSA had arranged for Suzanne and her husband, David Rago, to visit the School when I was director.). Suzanne suggested that I write to another friend of ours, Anita Ellis, former deputy director of curatorial affairs at the Art Institute of Cincinnati.

Anita responded: “Your vase is part of the [Rookwood] Brown Mat glaze line. The brown color of this glaze line ranges from dark chocolate to light brown, and is generally uneven in color or mottled, not unlike many finds from antiquity. Because this glaze line is not listed in any of Rookwood’s glaze notebooks, color identification sheets, or retail sales lists suggests that it did not sell well. I suspect that one had to like the browns of antiquity to appreciate it. … Like the other undecorated mat lines this one is considered a commercial ware product because it is undecorated and unsigned by any artist.

As for the impressed marks on the bottom, “2760” is the shape number. Peck’s book of shape numbers [H.Peck, The Second Book of Rookwood Pottery, p. 144 (privately published, 1985)] tells us that the vase was designed by John D. Wareham (1871-1954). [Our calyx krater was also designed by Wareham]. The date of the vase as you know is 1924. Carter discovered King Tut’s tomb in 1922, which gave way to a very desirable archaeological look to things for years. You also have an esoteric mark below the “2760.” … The commercial ware pieces that contain [such marks] are usually from more complicated molds, such as the one needed for your vase because of its shape and because handles needed to be applied.”

Copy of a Late Helladic II alabastron by Rookwood Pottery, 1924, bottom of vase. Kim Shelton Collection. Photo: Jack L. Davis.

Had these vases been special orders? I turned to Rookwood Pottery Inc. for help. Would they be able to provide a clue? There I struck out. The Rookwood archives were destroyed when the firm moved to Starkville, Mississippi in 1959.

Alan Wace in Cincinnati in 1924

At this point I decided to approach the problem from another angle. Had either Wace or Blegen been in Cincinnati in 1924? I got lucky. Although Wace’s diaries from this period are not preserved, public records came to the rescue. Wace had, in fact, been Charles Eliot Norton Memorial Lecturer for the Archaeological Institute of America (AIA) in 1923-24. In that capacity, he delivered two lectures about his excavations at Mycenae in southwestern Ohio: one at Miami University and one in Cincinnati. The Cincinnati chapter had been founded in 1905 but was reorganized in 1923-24 by William T. Semple, head of the Department of Classics at the university. Semple was also patron of the university’s excavation at Nemea, which in its inaugural campaign in 1924 would be directed by Bert Hodge Hill and Carl W. Blegen. The chapter grew from seven members in 1924 to 80 in 1925. By 1926-1927, Semple’s wealthy wife, Louise Taft, had become a Vice-President, and Cincinnati was described as “one of our best societies” in President R.V.D. Magoffin’s annual report.

I found an advertisement for the Miami lecture in a local newspaper, but none for Cincinnati. Jeff Kramer, archivist of the Department of Classics, wonders “if the Cincinnati stop wasn’t advertised to the public, especially since membership [of the society] was so small. Who knows? – maybe the Semples hosted it at Louise’s parents’ house on Pike Street. The parlor there is more than large enough.” That mansion is now the Taft Museum of Art.

It seems entirely possible that Wace visited Rookwood Pottery on the occasion of his visit to Cincinnati in January 1924 and supplied the design himself, as Lisa remembers the family tradition (although not with her mother). Susan Walker Longworth, whose ancestors had once owned the Taft mansion on Pike St., had been President of the Cincinnati society and was a life member. The Longworths were passionate about art and Greek Antiquity. But there is a smoking gun: her sister-in-law, Maria Longworth Nichols Storer, a patron of the arts and an artist herself, had co-founded Rookwood Pottery. Had the Semples helped to arrange the manufacture of the two alabastra for Wace on the occasion of his Norton lecture? One can even imagine that the Director of the ASCSA, Bert Hodge Hill, who had visited the Semples in November of 1923, supplied Rookwood Pottery with images of alabastra recently found by Wace at Mycenae — although there is no indication that he did so in his account of the trip included in a letter to Blegen.

Both Mycenaean object biographies have loose ends. The bottom line is that, although this post has become much longer over the past six months, I am unable to be certain about the precise roles that the goblets or alabastra played or did not play in Wace and Blegen’s relationship – there are only likely scenarios.

Failure in the Archives?

Despite the fact that Blegen’s professional archive at the ASCSA comprises 8 linear meters, while Wace’s in the Faculty of Classics at Cambridge fills 34 boxes, questions that might easily have been answered, were the principals alive, remain mysteries. The momentos that concern me in this post are, of course, of trivial importance in comparison to gaps that historians often face, especially when confronted with biographies of the disempowered and disregarded. That problem is, in fact, so extreme that it was chosen as the topic of a 2014 conference sponsored by The Centre for Editing Lives and Letters at University College London, titled “Failure in the Archives,“ a celebration of the “frustrations of archival research,” … “a forum to examine everything that doesn’t belong in traditional conferences and publications, from dead-end research trips to unanswered questions. The dangers of misstepping in the archive are endless, no matter how robust the finding-aids. ‘Failure in the Archives’ [aimed] to make that danger useful.”

Jill Lepore, David Woods Kemper ’41 Professor of American History at Harvard University, is one of the many who have wrestled with such issues. In regard to her biography of Jane Franklin, sister of Benjamin Franklin (Book of Ages: The Life and Opinions of Jane Franklin, 2013), she remarked several years ago:

“I think [Jane Franklin’s] story is allegorical in that it helps us to think about inequality. If people go around with the idea that the only people in the 18th century were John Adams and George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, then they are left with no ideas at all about inequality. The historical record is profoundly uneven and asymmetrical. These men left behind so many documents, so much paper, and these other people did not. So Jane’s life works as an allegory that reveals persistent forms of inequality, and what is more urgent to understand than inequality? … I took on a fairly ambitious sense of mission when I finally decided to finish this book — which I tried for many years to write and kept abandoning. I wanted to tell Jane’s story as a way to ask readers to think about how history gets written: what gets saved and what gets lost, what gets remembered and what gets forgotten, and what the consequences are of each of these choices.”

Do goblets and ceramic alabastra have their usefulness in the sense meant by the organizers of “Failure in the Archives”? In some small way I think they do. These objects were once woven in some way into personal relationships of individuals who shaped the field of Mycenaean studies. And the strength of these realia is demonstrated by their continuing ability to bind institutions and individuals: Cincinnati, Cambridge, and the ASCSA, schools cherished by Wace and Blegen, as well succeeding generations of scholars from Alameda to Manchester. As a student of material culture, I can appreciate that.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to all who have helped me research background for this post. These include: Anita Ellis, Ann French, Lisa French, Sean Hemingway, Riley Humler, Jeff Kramer, Joan Mertens, Dimitris Michalopoulos, Suzanne Perrault, Kim Shelton, Sharon Stocker, and Natalia Vogeikoff-Brogan. The Odyssey translation is from Kostas Myrsides, ed., Reading Homer: Film and Text.

Good stuff, Jack. Thanks for sharing. I love wine goblets; whenever I trek down to Seagrove, NC–the center of the famous potters’ district– I pick up another goblet.

Thanks Glenn,

Glad you enjoyed it.

As ever,

Jack

Another mystery this week. A couple days ago, Tim McNiven of OSU art history and Classics mentioned by coincidence to Shari that he had noticed a Rookwood alabastron at auction in 2015. The auctioneer was Riley Humler of humlernolan.com in Cincinnati. Riley put me in touch with the current owner and I bought it. But here’s the big reveal. It is inscribed to AJB Wace and dated 1924!

JACK DAVIS ASKED ME TO ADD THE FOLLOWING TO THE SAGA OF “WACE’S ALABASTRA”:

The mystery is beginning to unravel:

Lisa French has written me recently: “One thing I should point out in all these matters is that we did not exchange presents regularly with Carl and Libbie. They gave the parents a handsome silver tea service as a wedding present and Carl sent a Canakale lamp to me when he was working at Troy but I did not get presents from them each year as I did from others like Boethius – (wonderful children’s books which I still have) nor when they came to stay – which was fairly regularly en route to and from Greece…”.

Ann French also wrote: “I saw my mother on Saturday and told her all about the additional initialled Rookwood alabastron. Total news to her that there was another one. So we spent a happy afternoon discussing & speculating. We came up with a thought that it may have come back with the others and was given to my great-grandmother Fanny (Bayard) Wace who lived in St Albans. Her home, Leslie Lodge, was used as a base by my grandfather for many years until he was employed at the V&A from 1924 and found an apartment in London. While Fanny Wace died in about 1934, her sister Eugenia Bayard continued to live there for another 10 years or so which would have meant that the house was cleared and emptied out by relatives as my grandparents would have been in Alexandria. Just speculative thoughts – but would explain it turning up in the UK?”

In any case, the new, inscribed alabastron now resides in my house in Cincinnati, on the mantle aside other Rookwood treasures. Its previous owner hand-carried it to Cincinnati last weekend and I collected it yesterday from Riley Humler of Humler and Nolan, a major auction house for American art pottery.

This is clearly the presentation piece made for Wace on the occasion of his 1924 visit to Cincinnati. We can be fairly certain that he would have visited the pottery itself on that occasion. Jeff Kramer has written me: “ … when [Edward] Capps [Chairman of the Managing Committee of the ASCSA] was in town in 1923, he and [Ralph] Magoffin [President of the AIA] visited Rookwood Pottery. Could it have been a stop on a general tour of the city for visiting guests?” I think “yes.”

Alabastron inscribed to AJB Wace by Rookwood Pottery, 1924. Now in Jack L. Davis’s Collection.