The Artemision Shipwreck: Sinking Into the ASCSA Archives

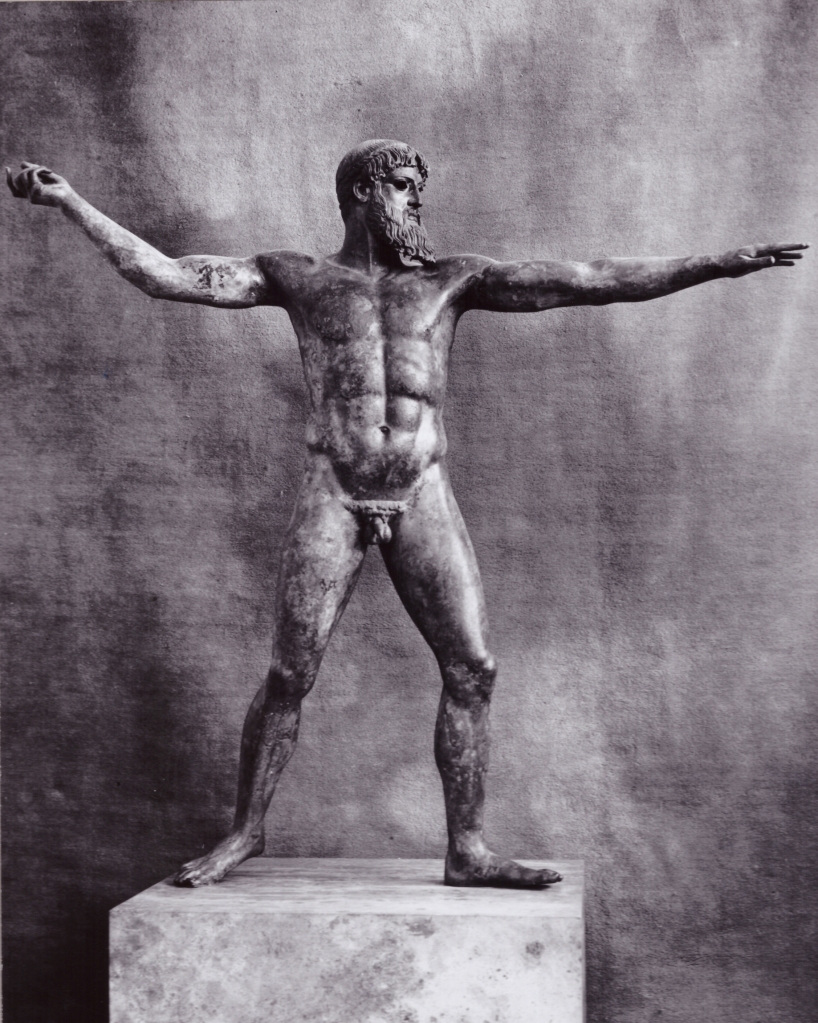

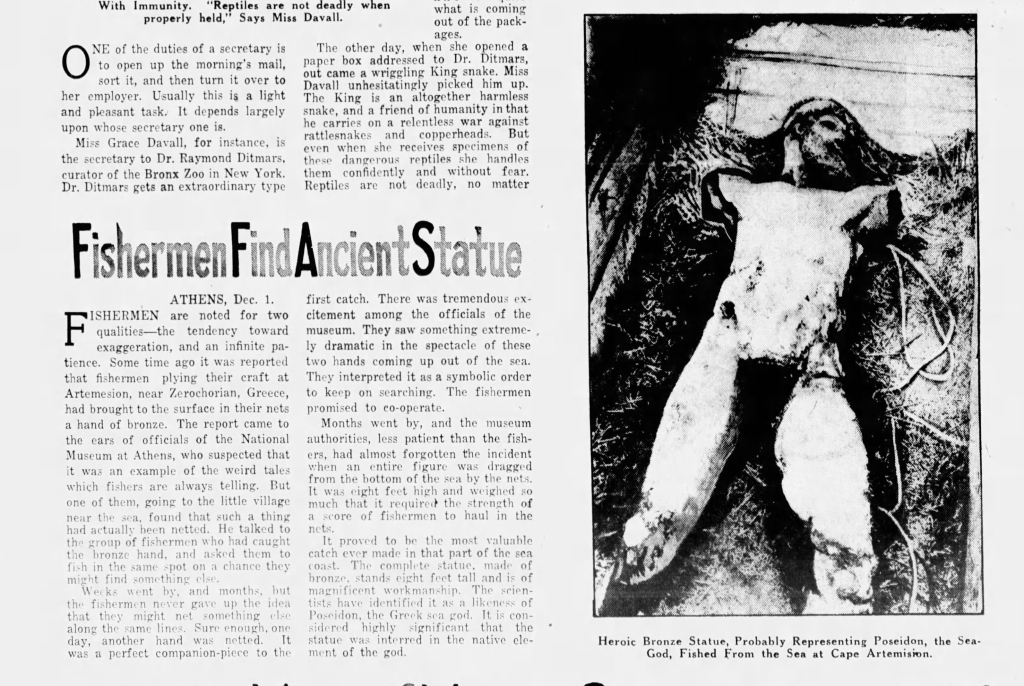

Posted: October 10, 2021 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Classics, History of Archaeology, Philhellenism | Tags: Artemision Jockey and Horse, Artemision Shipwreck, Artemision Zeus, Charles H. Morgan, George Hasslacher, George Mylonas, Georgios P. Oikonomos, Γεώργιος Οικονόμος, Philip R. Allen, Sean Hemingway 7 CommentsIn late 1928 the Greek and the international press published several articles and photos of a sensational archaeological discovery: a large bronze male statue found near Cape Artemision, in the north of Euboea. On central display at the Archaeological Museum in Athens since 1930, the statue is known to the public as the Aremision Zeus (or Poseidon).

Two years before, in the same area, fishermen had caught in their nets the left arm of a bronze statue that was also transferred to the National Museum in Athens. That discovery did not, however, provoke any further archaeological exploration in the area, most likely for fiscal reasons. But then in September 1928, the local authorities in Istiaia, a town in northern Euboea, were informed of illicit activity in the sea near Artemision. Acting fast, they sailed to the spot and caught a fisherman’s boat filled with diving equipment. Not only that, its crew had already pulled out the right arm of a bronze statue. A few days later the authorities were able to bring up from the bottom of the sea a nearly complete male, larger than life, statue. The first photos showed the armless statue laying on its back on a layer of hay (Note how the area of the genitals has been conveniently darkened in the newspaper photos so that the public would not be offended by the nudity of the statue.)

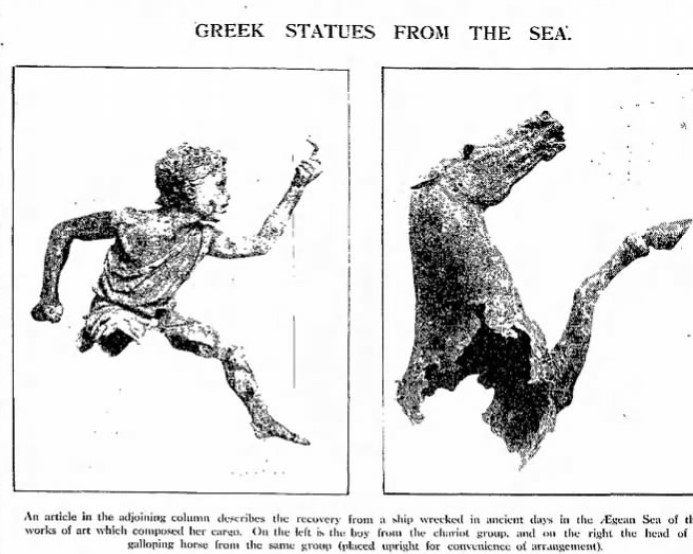

It was obvious that there was here an ancient shipwreck at the bottom of the sea, and that the Greek Archaeological Service needed to act fast before there could occur any new illicit diving in the area. However, underwater excavations are notoriously expensive since they require special equipment and trained divers. Nevertheless, by November of 1928, having secured 180,000 drachmas from the Greek government, the Archaeological Service sent the steamship Pleias, archaeologist Nikos Bertos, and a crew of divers to locate the shipwreck. Descending to a depth of nearly 45-50 meters (ca. 120-150 feet) and under extremely bad weather conditions, Bertos was able to retrieve the forepart of the body of a horse with its head and the largest part of the statue of a young male rider, who has since been known as the Jockey of Artemision.

In the early spring of 1929, Bertos, in another heroic effort, retrieved more parts of the horse and the rider, as well as some of the ancient ship’s ballast and pottery. Bertos promptly published an excellent account of his discoveries in the Archaeologikon Deltion (Αρχαιολογικόν Δελτίον) of 1929. In 2004, based on Bertos’s account and press clippings, Sean Hemingway, now Curator of Greek Antiquities at the Metrοpolitan Museum of Art, has offered us a new account of the discovery of the Artemision shipwreck in his book, The Horse and Jockey from Artemision (Hemingway 2004, pp. 35-42).

Zeus or Poseidon

Of the three bronzes, the easiest to conserve and display immediately was the nude, oversized male. By 1930, the impressive striding god with his extended arms was on full display in the National Museum. That same year Dutch archaeologist Hendrick G. Beyen (1901-1965) published the first monograph recognizing the statue as Poseidon. Soon afterward archaeologist Christos Karouzos (1900-1967) published a long article supporting the Poseidon identification. In 1944, George Mylonas, professor of archaeology at Washington University in Saint Louis (WUSL), published the first account in English that accepted Georgios Oikonomos’s identification of the statue as Zeus. (Oikonomos was the first to report officially the discovery of the statue in the Proceedings of the Academy of Athens in 1928.) Since then the majority of scholars have accepted the Zeus identification, although Poseidon has not been completely abandoned.

The Jockey and the Horse

Unlike the male statue, the public display of the jockey and horse was delayed for decades by the challenges presented in conserving them. In photos taken by Alison Frantz in the 1950s, we see the jockey displayed alone, on a metal stand. In addition, not everybody agreed that the jockey and the horse were contemporary. Ernst Buschor dated both the god from Artemision and the horse to the early 5th century B.C. Others such as Walter-Herwig Schuchhardt and Margarete Bieber argued for a Hellenistic date. In 1972 the restoration of the horse was completed and for the first time, the jockey and the horse were united and displayed as a single composition at the National Archaeological Museum (NAM). After a careful study of their stylistic features, Vassilis Kallipolitis (1910-1983), then director of the NAM, identified the composition as classicizing with a date in the middle of the 2nd century B.C.

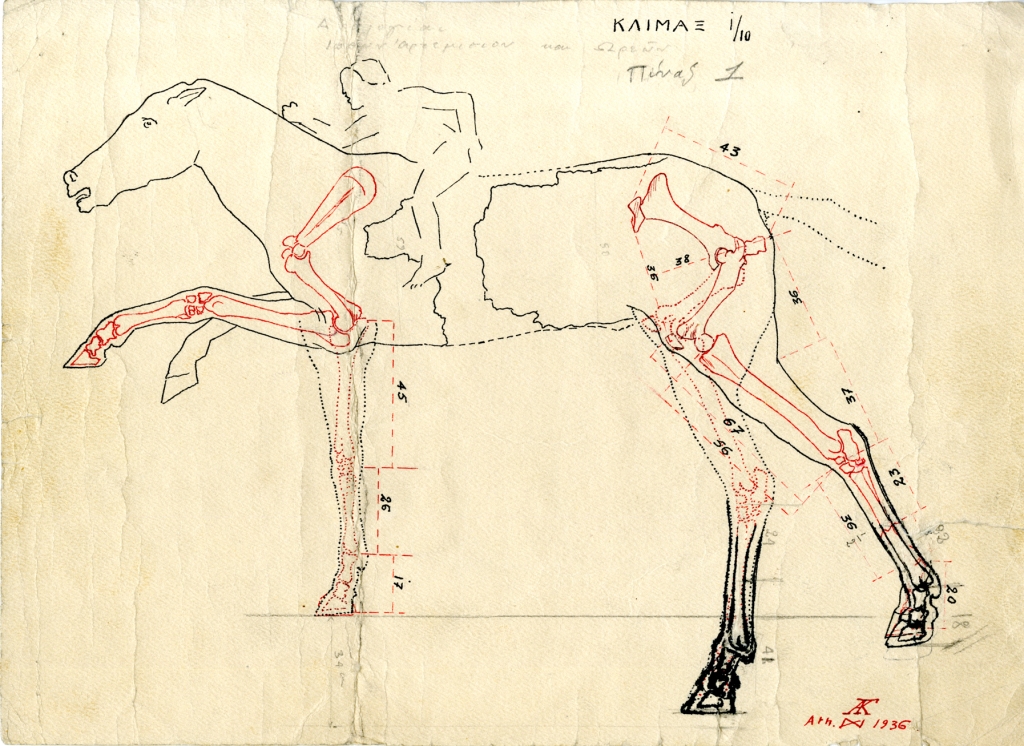

I borrow most of this information from Hemingway’s thorough study of the Jockey and Horse Group, where he reviews past scholarship and offers his own interpretation based on additional technical and chemical studies. But coincidentally, while Sean was preparing his publication, the ASCSA Archives acquired the personal papers of a Greek sculptor, George Kastriotis (1899-1969). The main motivation for acquiring Kastriotis’s archive was his connection with the Schliemann family. Kastriotis was the nephew of Sophia Schliemann, and his papers contained information about the Schliemann family.

Archival collections intercommunicate like “communicating vessels.” While processing the Kastriotis papers, we came across two detailed drawings of the Artemision horse. Why? Kastriotis was working as a conservator at the National Archaeological Museum in 1936 when more pieces of the horse were caught in a fishing net. “It was only in 1936 that the hindquarters and part of the body of a bronze horse were discovered by fishermen dragging the seabed with nets off Cape Artemision. An archaeological report in the Bulletin de correspondence hellénique illustrates this large fragment…” (Hemingway 2004, 42). And Kastriotis was trying to see, at least on paper, whether the new fragments belonged to the horse fragments that had been retrieved in 1928.

Hemingway, as did Kallipolitis, dates the group to the 2nd century B.C., further connecting the Artemision shipwreck with the sack of Corinth by general Mummius in 146 B.C. According to Pausanias, Mummius, after sacking Corinth, sent most of the city’s statues to Rome and some to Pergamon. The fact that some of the pottery retrieved from the shipwreck was of Pergamene origin has been used to suggest that the ship was sent from Pergamon to pick up booty from Corinth, unfortunately sinking off Cape Artemision on its way back (Hemingway 2004, 146-147). Other theories have speculated a different point of departure for the bronzes, including the sanctuaries at Dion, Delphi, Demetrias, and more recently the sanctuary of Poseidon at Onchestus in Boeotia, where recent excavations by Ioannis Mylonopoulos, Professor of Art History and Archaeology at Columbia University, and Alexandra Charami, Ephor of Boeotia, have discovered remains of several sacred building as well as metallic parts of harnesses. (See The Onchestos Archaeological Project.) This new discovery combined with literary sources, such as the Homeric Hymn to Apollo, about unusual chariot races with newly tamed colts at Poseidon’s precinct in Onchestos adds another candidate to the list of sanctuaries suggested for the original location of the Artemision bronzes.

American Interest

From Lucy S. Meritt’s History of the American School of Classical Studies (hereafter ASCSA or the School), we learn that the ASCSA was also briefly involved in the retrieval of the Artemision shipwreck in 1952. “Professor Mylonas who served as Annual Professor in 1951-52… in fall 1952 with S. A. Dontas and Chr. Karouzos directed the sea investigation of the ship found earlier off Artemision, this latter actually with a permit issued to the American School” (Meritt 1984, p. 60). “We employed five divers with two diving suits and a sailing boat equipped with appropriate machinery, and the ‘Alkyone’… The divers worked in the morning and until one in the afternoon; then the ‘Alkyone’ took over and in the afternoon dragged the floor of the ocean… Unfortunately, we have no find to report, but we were able to locate the ship which in 1928 yielded the bronze statues…” mentions Mylonas’s report to the School (AdmRec 204/4 folder 4). With this in mind I was able to identify some snapshots from the 1952 exploration in the George Mylonas Papers.

I became further interested in the Artemision shipwreck when, recently, I came across correspondence referring to it in the School’s Administrative Records, as well as in the Oscar Broneer Papers. The files I found, however, were not about Mylonas’s project; instead, they preserved correspondence from the years 1936-1938, and their content is not mentioned in either of the two published ASCSA histories. The key figure in the School’s effort to initiate new underwater research at Artemision in the 1930s was not an archaeologist after all, but an American industrialist: Philip R. Allen of Walpole, Massachusetts.

“I had luncheon with Mr. Allen in Boston and he was full of his archaeological interests in Greece. He hopes that there will be soon a favorable response to his proposal to [George] Oikonomos about the Artemesium project. The terms he proposed seem to me very generous, as I understood them—viz. if the Government would furnish the tug-boat with derrick equipment, and would agree to recompense the divers for their finds in some reasonable amount, he himself would defray all other expenses, including the wages of the men; and the Government would send an ephor to oversee the work,” wrote Edward Capps, the Chair of the School’s Managing Committee, to Oscar Broneer, Associate Professor of Archaeology at the School, on June 16, 1936. Mr. Allen was also the main sponsor of Broneer’s excavations on the North Slope of the Acropolis. The School was also hoping that Allen would pick up some of the expenses for the restoration of the Lion of Amphipolis, a project that was in the works at the same time. There was also talk between Capps and the President of the Board of Trustees, William Rodman Peabody, about inviting Allen to become a Trustee of the School.

Allen was chairman of Bird & Son, a company established in 1795 that owned paper mills and made roofing material. By the early 20th century the firm had expanded and built plants at various locations in Massachusetts and in other states. (By 1969 it employed nearly 2500 employees and produced such products as shoe cartons, asphalt shingles and siding, tack boxes, and frozen food container. In 1983 its name was changed to Bird Inc., and then again in 1990 to its current name Bird Corporation. For more, see Norwood Historical Society.)

Allen was also active on various boards, such as the Greater Boston Salvation Army Advisory Board, while in 1938 he was elected President of the Trustees of the New England Conservatory of Music. He appears in the list of the School’s Board of Trustees for the first time in 1943-1944, a position he held until 1962, the year of his death. “Mr. Allen was the last of the large Boston group of Trustees who virtually directed the Board’s activities during the early decades of this century. Well-grounded himself in the Classics, he was especially interested in the School’s excavations, and, fired with the romantic as well as the scientific possibilities of original methods of exploration, was a pioneer in encouraging underwater archaeology long before its recent widespread fame,” as noted in the School’s Annual Report for 1962-1963, acknowledging Allen’s earlier interest in the Artemision shipwreck.

Fishermen’s Fees

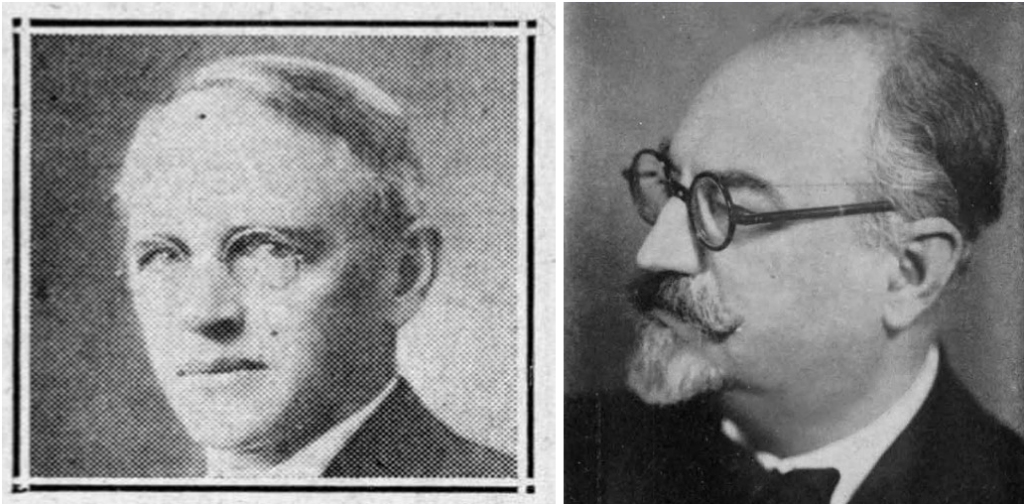

In reading Capps’s description of Allen’s plan, it struck me as odd that Allen was concerned about recompensing the local divers for their finds. A letter by Allen to Charles H. Morgan, the new Director of the School, written on August 27, 1936, provides more information about the project as well as the compensation of the divers. Allen refers to a meeting he had with Professor Georgios P. Oikonomos (Director of the Archaeological Service) in the presence of Aristeides Kyriakides, the School’s legal counsel. In so doing, Allen provides an interesting background story for his interest in the Artemision shipwreck.

For over two years Mr. George Hasslacher of New York and I have been discussing with representatives of the Greek fishermen, who claimed to be the ones who originally found the statues off Artemisium Point, the matter of further work there. They wanted to raise $10,000 in this country to carry on the work, claiming that they had seen other statues in the sea, especially the horse from which the Jockey had been pulled. They claimed to have exclusive permission from the Greek Government to do further work there and also that there would be considerable profit to those who put up the money because the Greek Government would pay well for whatever was found and if the Greek Government didn’t want the findings, they could be sold in other countries at good prices

ASCSA Archives, Charles H. Morgan Papers, box 1, folder 5

Both Allen and Hasslacher showed restraint in their communication with the fishermen and their U.S. representatives asking for “documentary proof,” which, of course, never came. When Allen went to visit Oikonomos, the latter explained “that such a project could not possibly be handled in this way; that there could be no large sum paid for any findings because the budget was small; that the best that the Greek Government ever did was to give some ‘gratification’ to the man who reported the finding and probably would pay for the expense that anybody went to in any given worthwhile finding.” Oikonomos further suggested that the Greek government could furnish some sort of a naval vessel, provided that Allen could raise the money to pay the expenses of the divers. Allen asked Morgan to continue the discussions with OIkonomos for a joint operation between the School and the Greek Government. Allen was willing to go along with whatever decision the two parties reached, with only one condition, “that Mr. Hasslacher and myself are to have the privilege of being on the expedition for as much time as we arrange to be there.”

Unfortunately two weeks after this letter was mailed, Hasslacher died tragically when he plunged sixteen floors from a building on Fortieth Street in Manhattan. George F. Hasslacher (1896-1936) was a chemist, Princeton Class of 1917, who was part of a family business, Roessler & Hasslacher Chemical Co., that produced chlorine products, hydrogen peroxide and metal cyanids. In 1933 he joined Snyder MacLaren Processes Inc., a company specializing in protecting metal surfaces from corrosion by depositing a thin film of lead on the metal surface. Clearly Hasslacher’s involvement in the Artemision project aligned with his scientific interests.

Following Hasslacher’s unexpected death, Allen continued to pursue the Artemision Project on his own, always in communication with the School’s leadership. However, Allen’s initial contacts with the representatives of the Greek fishermen now began to work against him. On September 25, 1936, Broneer shared with Capps a strange encounter he had had.

A gentleman, by the name Chester Valencia, who said he was a friend of Mr. Allen’s, came the other day and asked me concerning the project of searching for further statuary off the coast of Euboea… He said he had spoken to Mr. Allen before leaving America, and was now over here trying to make some kind of agreement with Mr. Gounalakis, who was formerly engaged by the government when the bronzes were brought to light. Gounalakis had given Mr. Valencia to understand that the government would grant a blank permit for searching the sea at this point, with the understanding that the finders were to receive all duplicates and have the money value of other pieces of sculpture.

ASCSA Archives, Oscar Broneer Papers, box 29, folder 3

Once again there was the issue of recompensing the divers for their finds. Broneer alerted by his conversation with Valencia went to see Oikonomos. And rightly so, because Oikonomos told him that Valencia had been misinformed by Mr. Gounalakis and “that the government would under no circumstances grant a permit of that nature” and that “Mr. Allen had been informed about this matter when he was here last year.” Broneer communicated Oikonomos’s reply to Valencia, who told him that “he considered the whole project fallen through.”

A search in newspapers.com about Valencia produced interesting information. A Californian from Ventura County, Chester (Chet) Esteban Valencia made his first appearance in the West Coast press in 1928 as a young stowaway in a steamer to Honolulu. “He is said to have been of an adventurous nature and so known among his friends when in Ventura” reported the local newspaper (The Ventura County Star and the Ventura Daily Post, 27 Sep 1928). He lived in Honolulu until 1932 working at the McBryde Sugar Plantation in Kauai. Ten years later his name reappeared in the newspapers. This time to announce his marriage to Sylvia MacGuffog of Westboro, Mass., the niece of State Senator Charles Cabot Johnson. It was probably through his marriage into the MacGuffog family and his relocation to Massachusetts that Valencia became acquainted with Allen, and somehow concocted the plan of profiteering from the Artemision project.

The same day that Broneer was communicating to Capps his concerns about Valencia, Morgan was also dispatching a letter to Capps outlining his plan to approach the King “to get his Majesty’s interest in the proposition, for I am sure it will appeal to him” and saying that he would not bother Oikonomos (obviously unaware of Broneer’s meeting) until he had “the King’s approval of the scheme” (AdmRec 318/4, folder 1, September 25, 1936).

One of Those Romantic Dreams

Morgan’s subsequent efforts to get Oikonomos’s ear about Allen’s proposal were fruitless. “He has been very evasive about the business all fall” complained Morgan to Capps (318/4, folder 1, January 14, 1937). Oikonomos asked to be sent a clear statement of Allen’s proposal. A few weeks later Allen mailed Morgan a statement of his proposal: “I would prefer to have this as a joint operation of the School with the Greek Government but if the Greek Government would prefer to have it as their project and the American School act as my fiscal agent, approving the bills that may be submitted covering the divers’ operations and rental of equipment (which I undertook to pay up to $1,000) that would be satisfactory to me” (AdmRec Box 204/4 folder 4, Feb. 1, 1937). According to the proposal, the Greek Government would furnish a suitable naval boat at its expense. And there was no mention of special compensation for the divers. Allen hoped that all negotiations would have progressed enough by the time of his arrival in March 1937, and that he would be able to watch the work off Cape Artemision in person. This did not happen but on May 29, 1937, after Allen had returned to the States, Morgan telegraphed: “Government will agree to Artemision Project” to which Allen immediately answered, “Congratulations Check Deposited with Treasurer Weld Today” (AdmRec 204/4 folder 4).

Despite the good news, the Artemision Project did not progress further. The next communication between Allen and Morgan dates from April 1938. “I have put off writing this letter way beyond the bounds of propriety, but I have constantly continued to hope that I might get some sort of commitment from the Ministry about your proposal concerning work under the sea at Artemision. I mentioned the matter to the authorities on innumerable occasions, and the gist of the answers has always been that the Government cannot refuse the offer, but that there is some difficulty with the conditions as outlined when the proposal was made. This, of course, is a sheer nonsense, for you will remember how carefully we left out all conditions from the proposal,” wrote Morgan to Allen on April 11, 1938 (AdmRec Box 204/4, folder 4). Morgan concluded that “they do not feel that can refuse the offer, but are unwilling to take any steps whatever to accept it.”

Despite having the School act as an intermediary and guarantor for the Artemision Project, I suspect that the Archaeological Service got cold feet once racketeers like Valencia and Gounalakis began trying to make their own negotiations. Oikonomos and other members of the Service were probably still aware of the litigation against the Greek State by the boat crew that had retrieved the Antikythera shipwreck in the early 1900s for not having been properly recompensed (Bafataki 2018).

“I have nothing else to do except to drop the matter… You mustn’t feel hurt about it. It was just one of those romantic dreams I wish we could have gone through…” was Allen’s final words on the Artemision Project .

AdmRec 204/4, folder 4, Allen to Morgan, April 27, 1938

And, it indeed remained just that — a dream.

FURTHER READING

Bafataki, V. 2018. “Η συμβολή των πολιτιστικών χορηγών και ευεργετών στην έρευνα και ανάδειξη της πολιτιστικής κληρονομιάς: Η περίπτωση του ναυαγίου και του μηχανισμού των Αντικυθήρων” (Senior thesis, Greek Open University).

Hemingway, S. 2004. The Horse and Jockey from Aremision: A Bronze Equestrian Monument of the Hellenistic Period, Berkeley.

Meritt, L.S. 1984. History of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1939-1980, Princeton.

Mylonas, G. 1944. “The Bronze Statue from Artemision,” AJA 48, pp. 143-160.

Mylonopoulos, I. 2016. “Ἀνασκαφὴ ἱεροῦ Ποσειδῶνος στὴ βοιωτικὴ Ὀγχηστό,” PAE 2015, pp. 219-229.

Varvarousis, P. and P. Papaevaggelou 2017. Ογχήστιος Ποσειδώνας: Λατρεία και πολιτική, Athens.

Hi Natalia,

Thanks for the great post on explorations at Artemision. It so happens that Iâm on the board of directors for the Norwood Historical Society, where the Bird & Son papers ended up. (The location of the factory is right on the town line, with most of the repurposed buildings now a commercial center in Walpole.)

Iâll take a look this week to see if we happen to have anything interesting about Philip Allen, but probably not since he lived in Walpole.

Hope you are doing well, Bryan

Bryan Burns Professor & Chair of Classical Studies Founders-Green Building Director

Co-Director, Eastern Boeotia Archaeological Project: Eleon Excavations President, Archaeological Institute of AmericaâBoston Society

pronouns: he, him, his bburns@wellesley.edu Founders 302B

>

Bryan, what a coincidence!!! Let me know if you find something. I had hard time finding an obituary of Allen, where there is more information about an individual. There is also a Philip R. Allen Chair of Psycology at Yale, but again I couldn’t find if it is related to “our” Allen.

Great article, Natalia. Talk about timing, I am doing the Persian Wars in class tomorrow and will be able to add some details about the Artemision shipwreck and the statue. Thanks for sharing. Glenn

Thanks Glenn. The story of the shipwreck will contribute an additional flare to the class.

Thanks, Natalia. Fascinating, as always. In the photo with Mylonas and crew, it would be worthwhile trying to identify some of those pictured, as they could be U.S. archeologists of the 50s. Sent from Mail for Windows From: From the Archivist’s NotebookSent: Monday, October 11, 2021 9:19 AMTo: tdinsmoor2@gmail.comSubject: [New post] The Artemision Shipwreck: Sinking Into the ASCSA Archives Natalia Vogeikoff-Brogan posted: " In late 1928 the Greek and the international press published several articles and photos of a sensational archaeological discovery: a large bronze male statue found near Cape Artemision, in the north of Euboea. On central display at the Archaeological Mu"

Dear Tessa, many thanks. I do not recognize any young archaeologists in the photos. I think it is just the crew. If George Dontas was in the photos (he would have been 29 years old), unfortunately I cannot recognize him.

[…] war. (For more on the bronze statue of Zeus or Poseidon from the Artemision shipwreck, read: “The Artemision Shipwreck: Sinking into the ASCSA Archives.) I went in search of clues and wanted to find out how exactly the Delphi Charioteer had come to […]