Sophia and Heinrich Schliemann: An Unusual Relationship (Pt. II)

Posted: December 26, 2025 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Exhibits, History of Archaeology, Modern Greek History, Women's Studies | Tags: family-history, genealogy, Heinrich Schliemann, History, Αγαμέμνων Σλήμαν, Ανδρομάχη Σλήμαν, Ερρίκος Σλήμαν, Σοφία Σλήμαν, Sophia Schliemann, travel 2 CommentsHappy Holidays! Inspired by the correspondence between Sophia and Heinrich Schliemann, Natalia Vogeikoff-Brogan and Leda Costaki curated, in the spring of 2025, a bilingual digital exhibition titled Sophia and Heinrich Schliemann: An Unusual Relationship (Σοφία και Ερρίκος Σλήμαν: Μια ασυνήθιστη σχέση), a version of which is presented here in two parts to reach a wider audience. Part I was published in this blog on December 6, 2025. We now continue with the second part of their captivating story.

Posted by Natalia Vogeikoff-Brogan and Leda Costaki, ca. 1,800 words, 10′ read time.

Recap (or Go to Part I)

Heinrich Schliemann came to Greece in 1869, having sold his businesses in Russia and divorced his Russian wife. Schliemann was looking for a new partner to share his dream of excavating the Homeric citadels of Troy and Mycenae, so as to prove that the Iliad was not a fairy-tale. In September 1869 Heinrich married Sophia Engastromenou. He was then 48 years old, and she was 18. Following an unsuccessful honeymoon, in the course of which the couple were on the verge of divorce, Schliemann left for Troy to start excavating. The couple did not separate, and in fact they became famous for their discoveries, remaining together till Heinrich’s death in 1890. In 1936 their children, Andromache and Agamemnon, donated their Papers to the American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

Married to a Sociopath

After their successful appearance in London, the Schliemanns left for their beloved Boulogne-sur-Mer, where they stayed for five weeks at the Hotel du Pavillon. From there, instead of returning to Greece, Schliemann established the pregnant Sophia in Paris, under the superintendence of French and Greek physicians, in order to forestall yet another miscarriage after the many she had undergone after the birth of Andromache. For the following months, up until the birth of Agamemnon in March 1878, Sophia remained alone in Paris with Andromache and their French nanny, with occasional visits from her brother Spyros and, towards the end of her pregnancy, from her mother. Heinrich paid them only one two-day visit on his way from Würzburg to Athens. He returned to Paris a week before his son’s birth on the 16th March 1878.

“Πώς λέγεις ότι δεν θα είσαι δια τα Χριστούγεννα μαζύ μας, είναι δυνατόν να μείνης περισσότερον των 6 ημερών εις Würzburg;”

“How can you say that you will not be with us for Christmas? Is it possible to stay longer than 6 days in Würzburg?” Sophia wrote him on December 11, 1877.

Photo: Sophia, pregnant with Agamemnon, with little Andromache in Paris, 1877. ASCSA Archives, Lynn and Gray Poole Papers.

David Traill considers that only a sociopath and egoist like Schliemann could leave his wife alone in a foreign country throughout her pregnancy (Traill 1986). Even Lynn and Gray Poole, authors of One Passion, Two Loves, who painted a very romantic picture of the relationship between Heinrich and Sophia, find Schliemann’s behavior inexplicable.

Sophia Reaches Her Limits!

Aside from Heinrich’s miserliness, another thorn in their relationship was his insistence on the curative properties of water, whether spas, cold baths or sea-bathing. He himself swam winter and summer. When in Athens he would go every morning on horseback down to Faliron. Even at Troy he never missed the chance of riding to the sea to bathe.

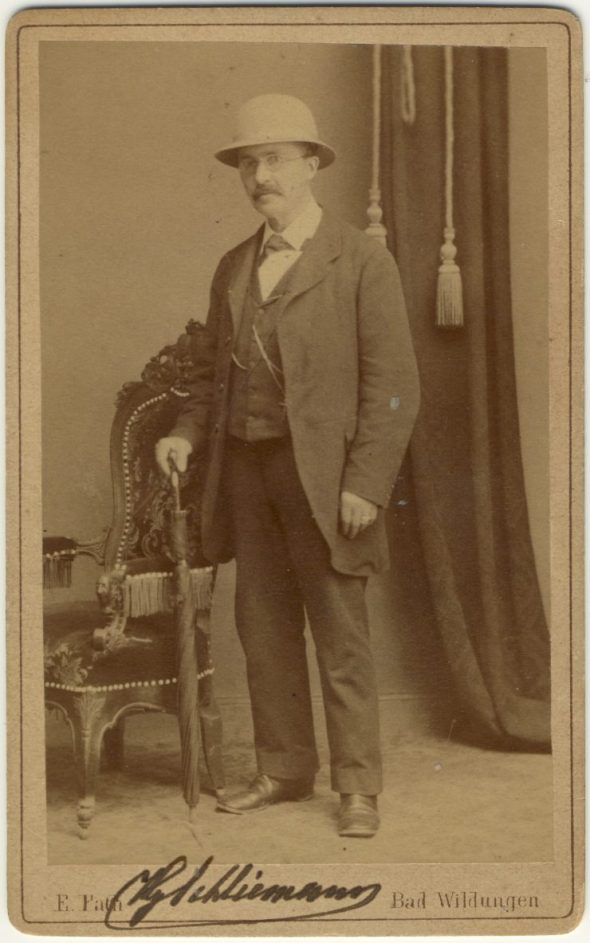

From 1880 the almost obligatory holidays would begin for Sophia and the children at some European spa in Germany or Austria. Schliemann was usually absent or would take the waters at some other nearby spa, as in the summer of 1883 when he was at Bad Wildungen in Germany while Sophia and the children went to Carlsbad and Franzenbad in Bohemia.

On August 22, 1883, Sophia wrote him from Franzenbad: ‘I have had enough of the baths…’ (‘Απηύδησα πλέον των λουτρών‘). Before that, she thanked him for the photograph he sent from Bad Wildungen, commenting humorously: ‘Your photograph […] is most expressive; I read my whole little Heinrich in it (‘αναγιγνώσκω μέσα εκεί όλον μου τον Ερρικάκη‘). Surely you thought of me at that very moment, for whenever you speak to me you wear that very expression.’ ASCSA Archives, Heinrich Schliemann Papers, Box 92, #703.

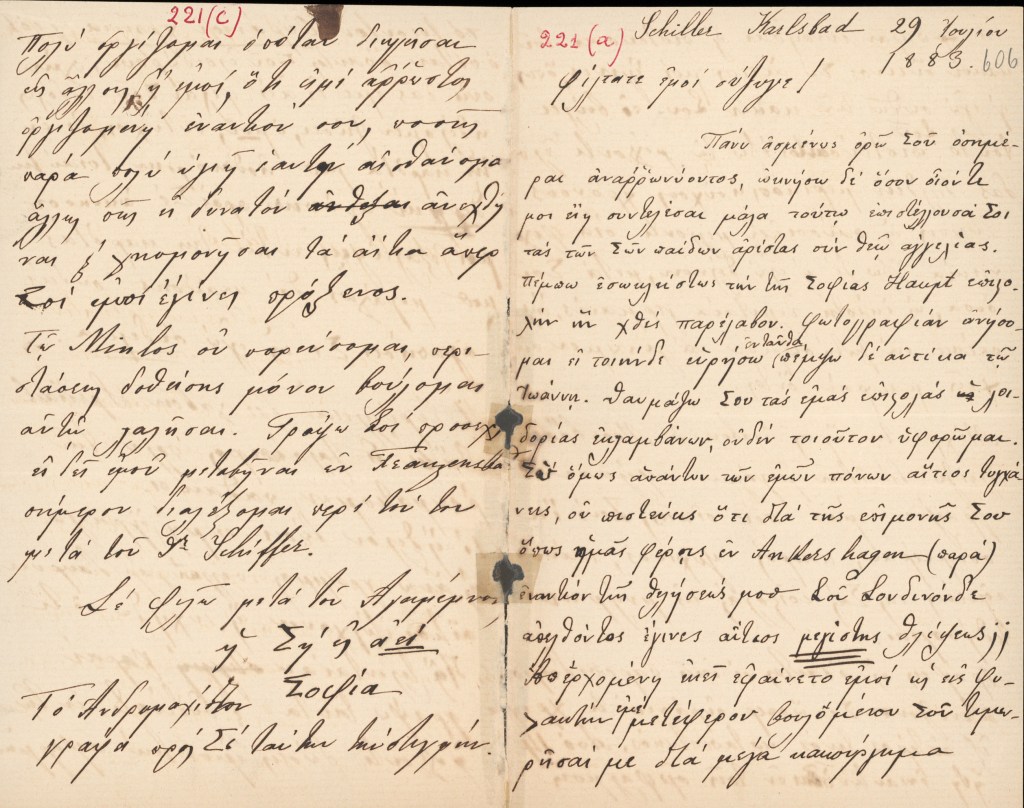

On July 29, 1883, with relations already strained after Schliemann had compelled Sophia and the children to spend several weeks with his family at Ankershagen, Sophia wrote to him from Carlsbad that the only way they could still find happiness was to live apart: ‘we must seek to be happy while living at a distance’ (‘πρέπει να ζητήσωμεν να γίνωμεν ευτυχείς μακράν όντες‘). And if she were ever to cease loving him, ‘you will weep greatly; no one will ever love you as I do -no one’ (‘μεγάλως θα κλαύσης, ουδείς αγαπήσει Σε ως εγώ ουδεμιά‘). She was also angered by Heinrich’s claims to others that she is supposedly ill.

On the contrary, she felt she was in excellent health, too healthy, in fact, to keep tolerating and forgiving him:‘I feel myself far too healthy; otherwise, how could I endure and forget the causes for which you became the source of my sufferings?’

ASCSA Archives, Heinrich Schliemann Papers, Box 92, #606.

Sophia’s most significant revolt happened at the end of 1885, when Schliemann was on holiday in Cuba, and she took it upon herself to make the important decision to cut short Andromache’s studies at a Lausanne school for girls and return to Athens. Sophia disagreed with the progressive principles of the school. Deep down, it is possible that she could not stand the idea of yet another ‘banishment’ from her beloved Athens.

One year later, at the end of summer 1886, having once more endured a ‘banishment’ to European watering places far from the sea she adored, she decided, without his approval, to take the children and go to Ostend on the Belgian coast.

“My dear papa”

With Schliemann absent for long periods, Sophia had the primary role in the upbringing and supervision of their children. In the Heinrich Schliemann archive there are more letters from Andromache, who was the eldest, and fewer from the younger Agamemnon. Sophia always gave Heinrich news of the children, and sometimes made them add one or two lines to her own letters.

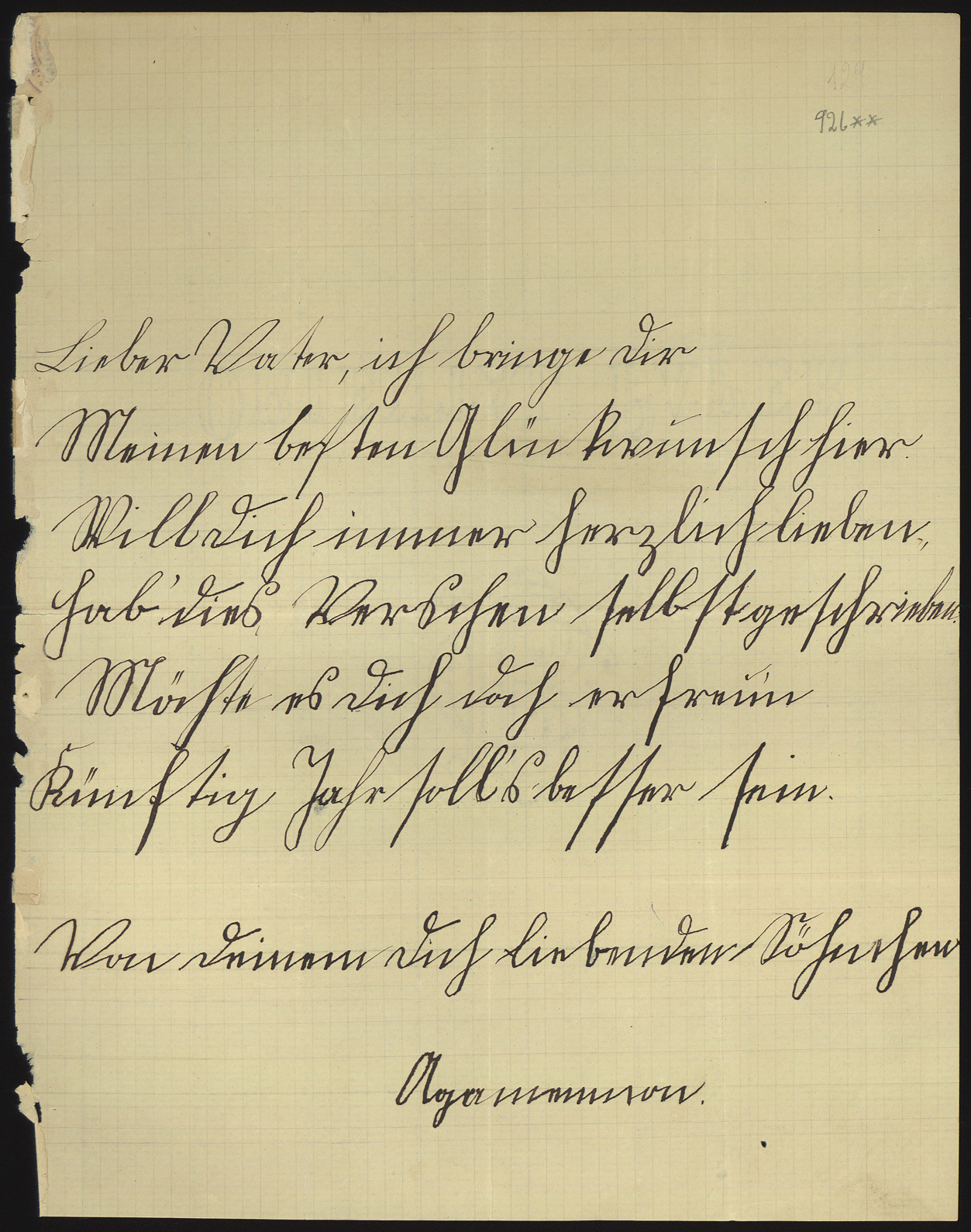

At the beginning of 1886, with his mother’s help, seven-year old Agamemnon (known as ‘papa’s child’ for he had taken after his father’s character), thanked his father, who was away on a trip to Cuba, for the rare stamps he sent, and expressed his regret that he was not yet old enough to travel with him. In the same envelope, Sophia enclosed another letter from little Memekos (his nickname) written in German so that Heinrich could witness his son’s progress.

Agamemnon and Andromache, ca. 1883. Agamemnon’s German letter to his father, 1886 (ASCSA Archives, Heinrch Schliemann Papers, Box 97, #926d).

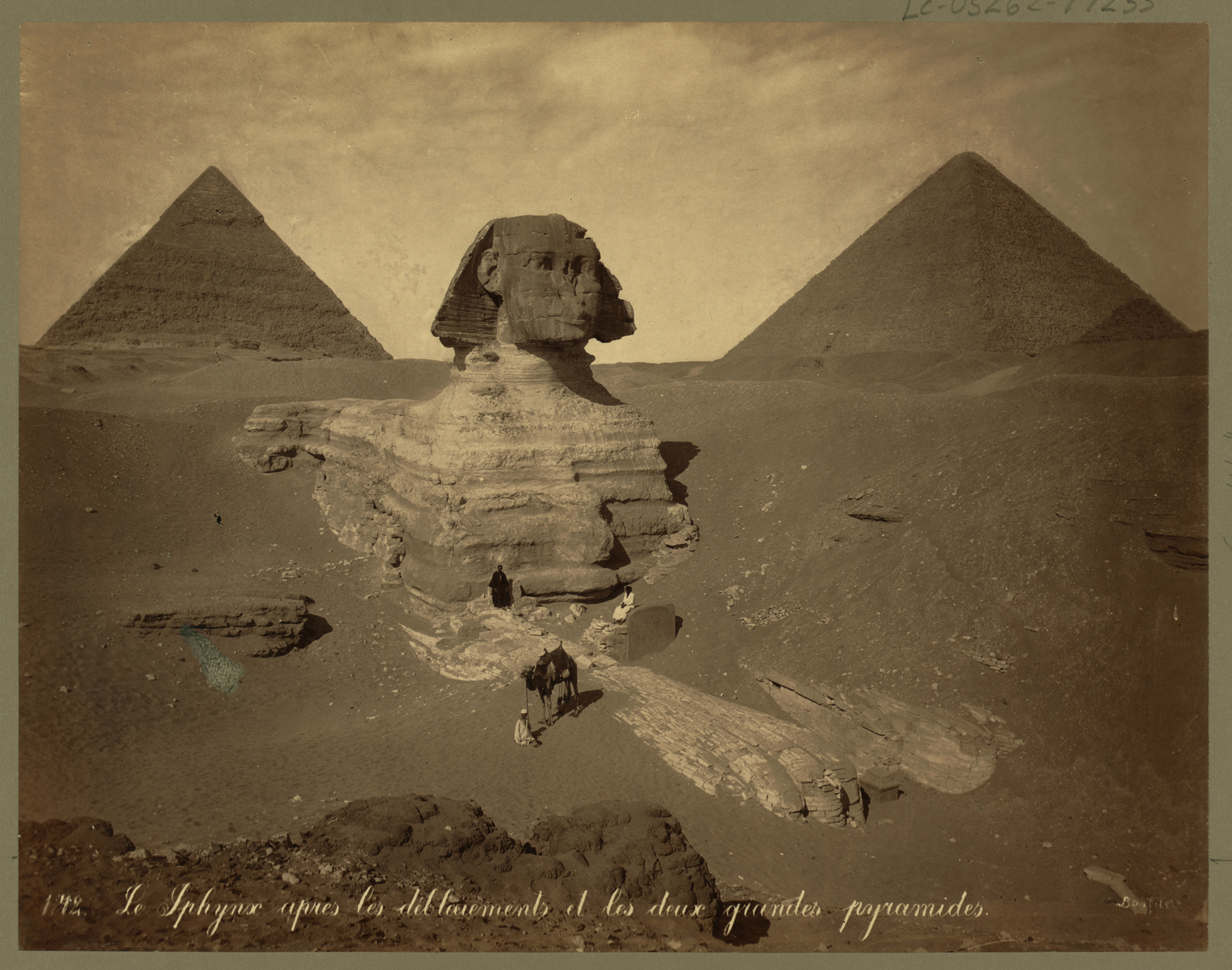

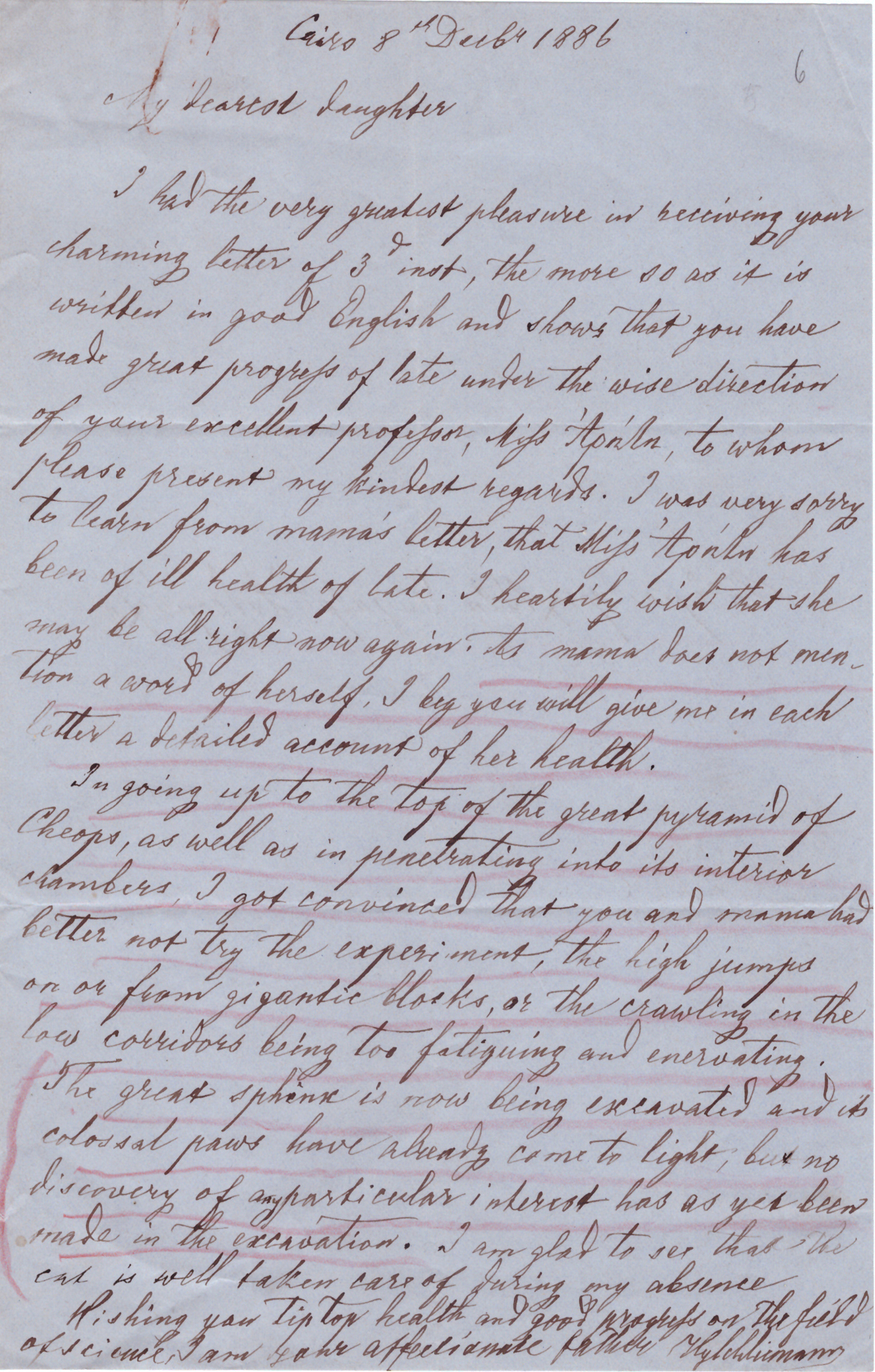

On December 8, 1886, writing from Cairo, Schliemann praised his daughter Andromache for her good English: ‘I had the very greatest pleasure in receiving your charming letter […], the more so as it is written in good English and shows that you have made great progress […]. In the same letter he informed her of the excavation of the Great Sphinx at Giza: The great sphinx is now being excavated, and its colored paws have already come to light […].’

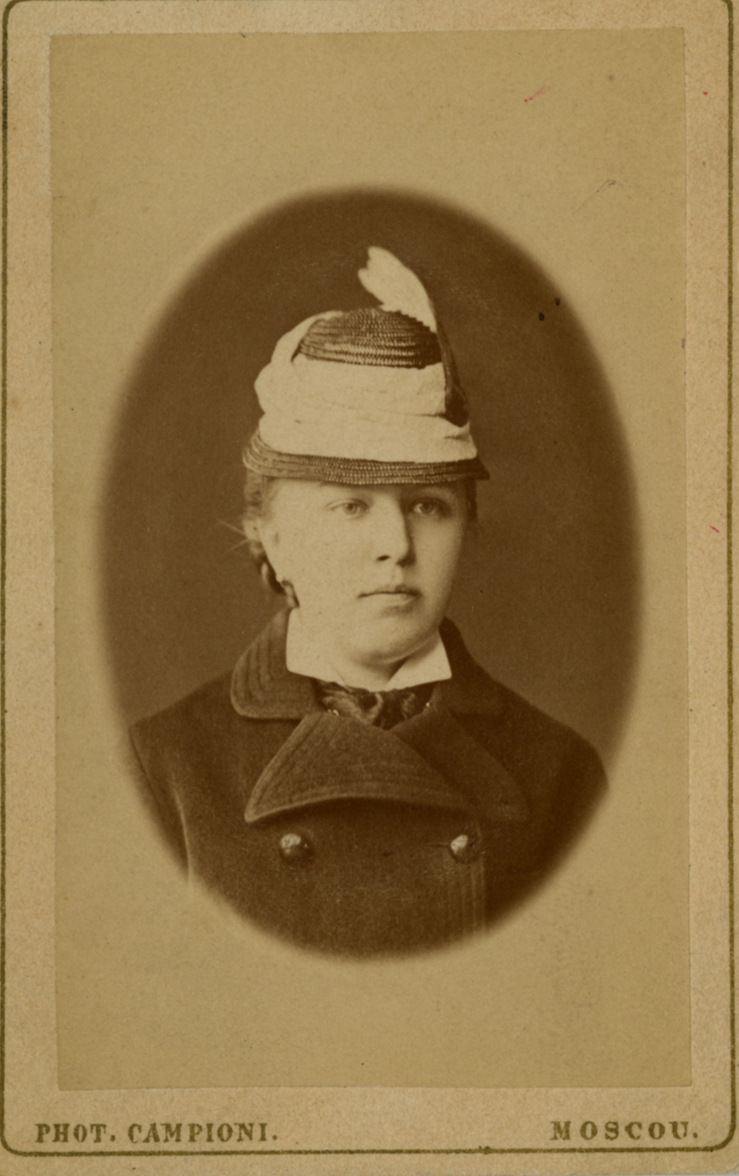

Andromache Schliemann, 1888; Schliemann witnessed the excavation of the Great Sphinx (Source: Bonfils Wikipedia Commons); Schliemann to his daughter, Dec. 8, 1886. ASCSA Archives, Heinrich Schliemann Papers

Schliemann also had three children from his first marriage with the Russian Ekaterina Lyschina: Sergei (1855-1939), Natalya (1858-1869) and Nadezhda (1861-1935). Schliemann was on his honeymoon with Sophia when he heard of the death of his daughter Natalya. In a letter to her father Sophia described that painful time: when the news arrived, ‘for three days he resembled a dead man’.

In the Heinrich Schliemann archive there are about 115 letters from Nadezhda and 411 from Sergei, which prove that Schliemann maintained close contact with the children of his first marriage. Since most of them, with very few exceptions, are written in Russian, we cannot reach a clear understanding of the relations between them. But it seems that Sophia had a good relationship with Heinrich’s children, at any rate with Sergei.

Sergei Schliemann, 1872; Nadezhda Schliemann, 1870s. Source: ASCSA Archives, Melas Family Papers.

“What God Has Joined Together”

The construction of the Iliou Melathron mansion took three years (1878-1880). It was Heinrich’s life’s dream, but not Sophia’s, who was emotionally attached to their first house in Mouson Street (Οδός Μουσών). The size and magnificence of the new house reminded her more of a museum than a home.

In an undated letter, likely written in 1879, while theIliou Melathron was still under construction, Heinrich wished that he and Sophia would celebrate there their silver and gold wedding anniversaries, ‘but also the weddings of our children, in health, in harmony, and in happiness’ (‘αλλά και τους των ημετέρων παίδων γάμους, υγιαίνοντες, ομοφρονούντες τε και ευδαίμονες’) [ASCSA Archives, Sophia Schliemann Papers #130].

On September 21, 1890, Schliemann celebrated their 21st wedding anniversary in Athens without Sophia and the children, whom he had sent to an Austrian spa. Alone and lost in thought, he reviewed the two decades of their married life, concluding that Sophia had been a beloved companion and partner, and a worthy mother:

‘[…] I see that the Fates have healed many of our wounds, but have also bestowed on us many joys; and as we tend to see the past through rose-colored spectacles, forgetting its sufferings and recalling only its moments of joy, I cannot praise our marriage sufficiently. For you have never ceased to be for me my beloved wife (άλοχος προσφιλής), a pure-minded companion (εταίρος αγαθός) and trustworthy guide in difficulties (κυβερνήτης εν ταις δυσκολίαις πιστός), as well as a gentle fellow-traveller and remarkable mother (συνέμπορος φιλόφρων και μήτηρ των ου τυχουσών)’ (ASCSA Archives, Heinrich Schliemann Papers, Copybook 43, 20).

Schliemann died of postoperative complications at Christmas in 1890 at Naples, on his way back to Greece. Only shortly before, he had sent two telegrams to Sophia, asking them to wait for him for the Holidays: ‘Come state? Arriverò sabbato mattina.’

After Heinrich’s death, Sophia lived in the Iliou Melathron until 1926, when she moved to Palaio Faliro. The Iliou Melathron was for many years a social and intellectual landmark of Athens, where Sophia and her daughter Andromache presided hospitably over Schliemann’s posthumous fame.

Sophia Schliemann, ca. 1880s, and at an older age.

References

Poole L. and G. 1967. One Passion, Two Loves: The Schliemanns of Troy, London.

Trail, D. A. 1986. “Schliemann’s Acquisition of the Helios Metope and his Psychopathic Tendencies,” Myth, Scandal, and History: The Heinrich Schliemann Controversy and a First Edition of the Mycenaean Diary, ed. W. M. Calder III and D. A. Traill, Detroit, 48-80.

Thanks, Natalia. Fascinating, as always. Best wishes, Tessa Dinsmoor

Thank you Tessa for being a committed reader of the blog.