Where There’s Smoke There’s Fire: De Waele’s Story

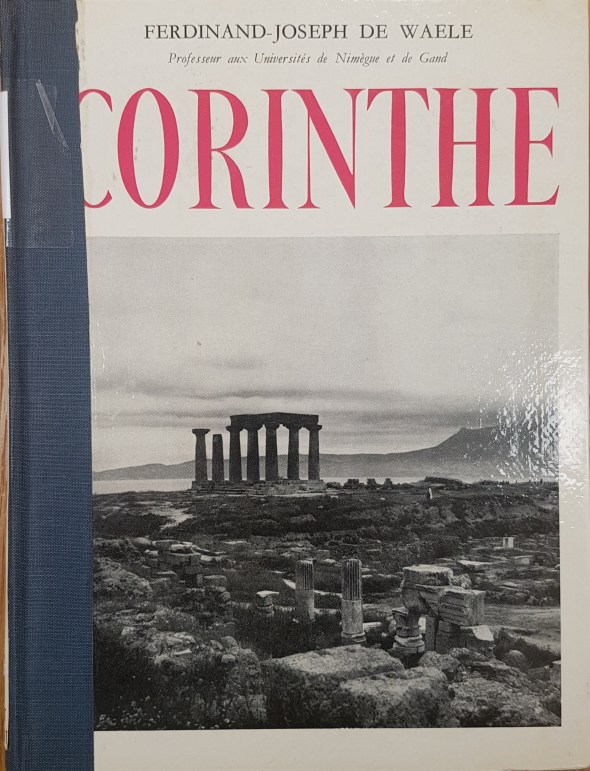

Posted: February 7, 2021 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Classics, History of Archaeology | Tags: Ferdinand Joseph Maria de Waele, Louis E. Lord, Oscar Broneer, Richard Stillwell 14 CommentsThe jumping-off point for this story was an odd comment that Louis E. Lord made in his History of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens about a Belgian archaeologist who was active at the School from 1927 until 1934. “Ferdinand Joseph Maria de Waele, Assistant in Archaeology for six years (1929-1934) was not reappointed. He had served well as an excavator, his work at the Asklepieion had been competent. But he never made a final report for publication, and the manner of his departure left behind him an odor of unsanctity highly offensive to the School” (Lord 1947, p. 246). Lord was referring to an accusation of smuggling antiquities made against de Waele. But was it true? A simple Google search showed that Ferdinand Joseph Maria De Waele (1896-1977), after leaving the American School, went on to have a distinguished career as a professor of archaeology at the Catholic University of Nijmegen in the Netherlands and, later, at the University of Ghent.

De Waele applied to the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or the School hereafter) for Associate Membership in the spring of 1927. He had just completed his doctoral dissertation, titled “The Magic Staff or Rod in Graeco-Italian Antiquity.” In a letter to Carl W. Blegen, Acting Director of the School in 1926-1927, de Waele explained why he had chosen to apply to the American School and not to the French School (which often hosted Belgian students): “My grandfather, having immigrated in the U.S. in 1875… was an American citizen and all my uncles and aunts [were] also American citizens” (ASCSA Archives, Adm Rec 108/1 folder 8, February 9, 1927). By working as a high-school teacher at The Aloysius College in The Hague, de Waele had saved enough money to spend a few months in Greece- at least, this was his initial plan.

As it happens, soon after his arrival in Athens, the School assigned de Waele to the Corinth Excavations, then under the direction of Benjamin Meritt, who was clearing the area along the Lechaeum Road. In this project, Merritt was assisted by Oscar Broneer, R.S. Darbishire (about whom I have written in the past), de Waele, and others. With funding from the University of Cincinnati, the same staff began excavations at the Odeum in the summer of the same year (1927). The two northern Europeans on the dig, Broneer (Swedish-American) and de Waele, who also happened to be slightly older than the rest of the group, soon began a life-long friendship. In the ASCSA Annual Report for 1927-1928, Edward Capps announced that Broneer “had been made Instructor in Archaeology and Dr. Ferdinand de Waele [had] also been given a staff position as Special Assistant in Archaeology on half-time appointment.”

In justifying the reason for these two new positions, Capps wrote about Broneer that “he had become a skillful and scientific excavator, had successfully conducted the Summer Session and School trips, had produced an excellent study of Greek Lamps for the Corinth Publications…”, and about de Waele that he was “a thoroughly trained archaeologist after the European fashion” who proved “from the outset to be a valuable assistant at the excavations at Corinth” (AR 1927-1928, p. 27). This ad hoc appointment would develop into a long term position for de Waele, which he held until 1934 (i.e. through Rhys Carpenter’s directorship of the School [1927-1932] and part of Richard Stillwell’s [1932-1935]). Over the next few years, de Waele would uncover the Roman Market and the Greek Stoa north of the Temple of Apollo (De Waele 1930; 1931), the Sanctuary of Asklepios (De Waele 1933), the Fountain of Lerna, and the Early Christian Cemetery (De Waele 1935).

However, despite these successful campaigns at Corinth, in the aftermath of the 1929 market crash, the School initiated over several years a series of budget cuts that eventually affected de Waele’s position. On March 4, 1933, Stillwell wrote to his predecessor about de Waele: “May I ask a word of advice? The de Waele question, re: being in charge during the summer, was hinted from home, as being not a welcome nor even a legitimate arrangement.” Stillwell was referring to the fact that de Waele had acted as Director of the School during Stillwell’s summer vacation in 1932. Stillwell was hoping that the same arrangement could be made for the summer of 1933. “I should dislike being on the horns of the dilemma as to whether it was up to me to stay or to make either Oscar [Broneer] or Filipp [Frantz, the Manager of Loring Hall] stay. Could you suggest some way of presenting the de Waele matter in a diplomatic way?” (Adm Rec 1001/1 folder 4).

The problem was more complicated, however. For reasons that are unclear, de Waele had acquired a strong enemy on the School’s Managing Committee. That person was Louis E. Lord (1875-1957), Professor at Oberlin College and the soul of the School’s summer session program. In the summer of 1932, there had occurred some incident between de Waele, who was acting in place of Stillwell, and Lord, who was leading the School’s Summer Session. Lord complained about de Waele’s “Prussian dictatorship” (Adm Rec 318/3 folder 5, June 15, 1932), although it is not clear how the two men crossed swords, threatening not to come in the summer, if “de Waele was to be left in charge.” (Adm Rec 1001/1 folder 4, March 4, 1933).

Louis E. Lord, ca. 1940.

Lord’s opinion must have prevailed in the meetings of the Managing Committee, for in May 1933 Capps announced to Stillwell that “the Executive Committee in their recent communications [were] practically unanimous in the view that this [was] the best time for the termination of [De Waele’s] appointment” (Adm Rec 318/3, folder 5, May 2, 1933). Stillwell voiced his objections but Capps left no room for disagreement: “You certainly would not be happy if in order to provide de Waele’s stipend a cut were made in any of the leading items of the School Budget, such as Library, Grounds & Buildings, etc.” He also advised Stillwell to “release him [De Waele] from all excavation activities from now on and let him devote himself exclusively to the preparation of his materials for publication. I should think it would be quite possible for him to get through by November, or at any rate to have so amassed his material that he could easily finish it up at home without revisiting Corinth” (Adm Rec 318/3, folder 5, May 6, 1933).

De Waele wrote to Capps to express his gratitude to “the School for all the courtesy and opportunities which he had enjoyed and reassured him that “it was not only his obligation but also a duty to prepare his report in the best possible manner on the excavations at the Asklepieion and the Fountain of Lerna” (Adm Rec 318/3, folder 8, January 2, 1934). On a personal front, while in Greece, Joseph (de Waele went by his second name) had married the beautiful Irene Lelekou. In the rich photographic archive of the Corinth Excavations there is an endearing photo, from about the same time, of Joseph with a baby, most likely Paul Broneer. (In the photo, de Waele is misidentified as Georg von Peschke and the baby as Jos de Waele, who was not born until 1938, three years after de Waele’s departure from Corinth.)

A Most Disturbing Report

The troubles with de Waele began in the summer of 1934. In September of that year, Stillwell, who had already dealt with Ralph Brewster’s theft of the Siphnian herm in 1932, was informed that de Waele had taken antiquities out of the country without permission:

“I was informed that this summer you had acquired, by purchase, some antiquities, for which you asked, and received permission from the authorities to take with you to Holland. But, according to the report, you had also acquired other antiquities concerning which you made no representations to the archaeological authorities, but took them out or caused them to be taken out of the country without permission.”

Stillwell, obviously distressed and annoyed, continued: “Such an action, on the part of anyone who had been connected with the School would be a most serious breach of confidence, both toward the School, and toward the Greek Archaeological Authorities, who have always shown themselves most willing to cooperate with us in granting any permissions that it is in their power to allow… We have always enjoyed the greatest degree of freedom in the conduct of our work, due to the confidence that we have been fortunate enough to inspire in the authorities.” He concluded that he was writing this letter with reluctance “because of our long acquaintance and friendship” (Adm Rec 318/3, folder 10, October 5, 1934). I have not been able to locate de Waele’s explanatory letter, but from Stillwell’s answer, it appears that his explanations were sufficient. The issue of conflict with the Greek authorities was a white lekythos, and de Waele claimed that its export had been approved.

“Το δις εξαμαρτείν…”

We would not have known that there was a second attempt by de Waele to export antiquities without permission, were it not for the Oscar Broneer Papers. The documents supporting his second brush with the law are not found in the School’s Administrative Records but in the personal papers of Broneer, who was Acting Director in the summer of 1935. On August 30, 1935, the School received a letter from the Minister of Religion and Education stating that the Customs Office had found in de Waele’s luggage undeclared antiquities which had been hidden in a special box labeled “objects of household use” (κεκρυμμέναι εντός ιδιαίτερου ξύλινου κιβωτίου χρησιμεύοντος κατ’ ιδιόχειρον σημείωμά του δι’ εναπόθεσιν αντικειμένων οικιακής χρήσεως”) [ASCSA Archives, Oscar Broneer Papers, box 29, folder 2].

Like Stillwell, Broneer found himself in the awkward position to have to write a distressing letter to his friend: “Quite apart from the ethical questions involved, which are serious enough, you have placed the School in a bad predicament. I have no choice but to hand the letter over to the new Director [who would have been Edward Capps] when he comes… The letter was sent by mistake to the Agora office and had been opened and read by others. I have done my best to keep the news from spreading further, but I cannot and would not try to hide from the Director… I feel hurt and annoyed as your friend, as a colleague, and, above all, as staff member of the School, whose reputation for honesty and upright dealings has hitherto never been, so far as I know, justly questioned” (Oscar Broneer Papers, box 24, folder 1, Broneer to de Waele, September 4, 1935). Note that Broneer did not refer to the incident of the previous year, which shows that Stillwell had tried to protect de Waele’s reputation.

De Waele’s reply to Broneer surprised me. Instead of trying to find ways to justify his act, as had done before with Stillwell, de Waele wrote a long and desperate letter admitting his guilt:

“A totally ruined and wrecked man writes to you. A man who caused his own ruin to come by a stupidity and evil deed as never before. I do not wish to be pathetic but I feel that I am finished, finished forever and that I am carrying with me the conscience of being guilty.”

ASCSCA Archives, Oscar Broneer Papers, box 24, folder 1, September 9, 1935.

In another letter to George Oikonomos, the Director of the Archaeological Service, de Waele stated that he had no accomplices in his deed and that his motive was not “to take profit or earn gain” but “to contribute to the love for Greece in other people.” In addition, de Waele also admitted to Broneer that in addition to smuggling out purchased antiquities, he had also tried to take out objects from the Corinth Excavations in order “to make casts of them” so that he could complete the publication of his excavations at Corinth. At a more personal level, de Waele confessed that he felt “as the murderer of [his] good wife whose kind reproach is a needle in my heart.”

De Waele ended his letter by making a very strange offer to Broneer. Since he rightly assumed that he would not be allowed to return to Corinth, de Waele suggested that Broneer publish one of his manuscripts: “I shall offer this as an anomymous gift to the School in order to repair a little bit the evil I did… Please accept my manuscript of the Early Christian inscriptions without any mention of me, just as if you did it. That’s the favor I ask you and nobody will know about it” (September 9, 1935). Three days later, in another letter, he asked Broneer to keep the matter “as secret as possible” even from Capps (Oscar Broneer Papers, box 24, folder 1, September 12, 1935).

What de Waele had hidden from Broneer came up during the latter’s visit to Oikonomos: “Oikonomos also told me certain things which I did not know and which you did not mention in your letter. He said that last year you had taken out some vases which you had not declared and that a certain amount of “fasaria” [fuss] had been made then. Looking up the official correspondence of the Director, I found that this was correct. You must recall some communications from Stillwell about this matter. Mr. Oikonomos also told me you had declared one vase this year to be used as a foil for smuggling out the others” (ASCSA Archives, Oscar Broneer Papers, box 24, folder 1, September 13, 1935).

Time Heals All Wounds

The fact that de Waele was able to continue his life and career largely unscathed from his earlier acts is due to Broneer’s magnanimity (he did not believe, as he wrote, “in throwing out the baby with the bathwater”). Capps also had agreed “not to take revenge” in the hope that de Waele would complete and turn in his manuscript on the Asklepieion in due time. Broneer warned his friend not to entertain any false hopes about working again in Corinth while trying to offer some comforting words: “ ‘Tiden laker alla sar’ [time heals all wounds]. You are not an old man yet; don’t try to rush matters at present. You have made your apologia, it is better to let that soak in before you try to take the next step” (Oscar Broneer Papers, box 24, folder 1, September 13, 1935).

There is no follow-up correspondence in the Broneer papers until 1939. In the Director’s files, however, there is a letter that shows that de Waele made plans to come back to Greece in the spring of 1937, as the representative of his university at the festivities for the Centennial of the University of Athens. Charles Morgan, the School Director since 1936 and an old friend of de Waele’s from Corinth, asked him to reconsider his intention of coming back. “Through the good offices of the department of archaeology, none of the unfortunate affair of the summer of 1935 ever appeared in the Greek newspapers. This was a difficult matter to arrange, and was done only with the idea that the School itself should suffer no reflected discredit from it… The Customs authorities, however, are not under the same jurisdiction. There is not the slightest doubt but what the incident is still fresh in their minds…” (Adm Rec 1001/1, folder 10, March 9, 1937). Morgan was afraid of a press leak. De Waele delayed his response to Morgan’s letter for a month. By then he had arrived in Greece, and since he had not encountered any problems with the Custom Authorities, he felt confident that the old matter was behind him “unless a new initiative is taken from a side, which is under your jurisdiction” de Waele conveyed to Morgan on April 14, 1937 (Adm Rec 1001/1 folder 10).

The high turnover of directors at the School in the 1930s (five directors in ten years) worked to de Waele’s benefit. The following summer (1938) he was at the School’s premises in Athens discussing with Lamar Crosby, the new ASCSA Director, the publication of the Asklepieion and the Lerna Spring. On leaving he left a draft of his manuscript with Crosby, who thought that it required a lot more editorial work “than a mere revamping of English” (Adm Rec 318/4, folder 2, Crosby to Capps, September 22, 1938). In 1939, de Waele was inquiring whether he could continue his study of the Christian inscriptions at Corinth, but Crosby was uncertain whether the Greek authorities would allow him to do so: “I have been told that they were rather outspoken during the term of my predecessor against permitting you to do further archaeological work in Greece” Crosby warned de Waele (Adm Rec 1001/1 folder 13, letters of May 27 and June 3, 1939).

Publishing the Asklepieion

As late as 1945, De Waele continued to believe that he would be the one to publish the Asklepieion (Oscar Broneer Papers, box 24, folder 1, September 9, 1945). The appointment of Louis Lord as Chair of the School’s Managing Committee in 1939 was the defining factor that led to removing the publication of the Asklepieion from de Waele. Ever since the unknown incident of 1932, Lord harbored negative feelings about de Waele, whose subsequent actions had only justified a low opinion of him.

The School’s Publication Committee had its annual meeting in May 1945. There it decided to cancel a number of outstanding assignments and reassign the publication of the Asklepieion to Carl Roebuck (1914-1999), a young scholar who had been a student of the School (1937-1940) and received his PhD from the University of Chicago in 1941 (AdmRec 208/19, folder 11). In late summer of 1945, Louis Lord received a letter from de Waele who “suggested going back to Greece (at our expense) to get further details” in order to finish his manuscript. De Waele also thought that it would take “some months” before it would be ready for submission.

Lord’s letter to Paul A. Clement, Managing Editor of the School’s publications, made fun of de Waele’s promise to deliver in “some months.” “That phrase is even more remote than the ‘almost immediately’ with which we are all too familiar. [Bert Hodge] Hill’s and [William Bell] Dinsmoor’s have been ‘almost immediately’ ready for more than twenty years. Judged by that, ‘some months’ would mean the next generation” (Adm Rec 208/22, folder 14, October 8, 1945). In a follow-up letter Lord asked de Waele (since he was not allowed to return to Corinth) to turn over his manuscript to Clement with the understanding that a second scholar would make revisions and prepare it for publication. “The alternative, which I don’t like to contemplate, will be to ask one of our Fellows to take the material and your preliminary reports and prepare the publication entirely de novo” (October 19, 1945).

By the end of 1945 de Waele had submitted to Clement a manuscript of 220 pages that covered the first part of his work and dealt with “The History and Archaeology of the Asklepieion Disctrict.” He wrote the Publication Committee that he also intended to mail “very soon” the second part, “An Inventory of the Finds in the Asklepieion District”. The Committee, however, found de Waele’s manuscript hardly acceptable: “It is written in incorrect and at times rather absurd English, and the general organization and exposition of the argument in many of the sections can and should be improved… it is necessary to check every description, every statement of fact…”. In addition, it was formally announced that Carl Roebuck would be the one revising the manuscript under Broneer’s general supervision (Adm Rec 208/19, folder 12, Report of the Chairman of the Committee on Publications, May 11, 1946). De Waele never sent the second part. Roebuck published the Asklepieion under the title: The Asklepieion and Lerna. Based on the Excavations and Preliminary Studies of F. J. De Waele (Princeton 1951). In the preface of the book Roebuck wrote that he had the opportunity to discuss the publication with de Waele in Amsterdam and that de Waele was “in agreement with the views which are expressed in the text.”

In the Realm of Friendship

After a breach of a few years, Broneer and de Waele resumed their old friendship at the end of WW II. The loss of friends and colleagues, as well as other personal suffering, bridged the gap in their relationship; there are several long letters from de Waele in the Broneer papers.

“My brother-in-law was kept in jail for several months by the Italians. My cousin was shot” wrote de Waele on September 9, 1945; Nimeguen, where he and Irene lived with their three children, had been severely damaged in 1944 “by a British ‘mistake’ that destroyed the heart of the city.” On a happier note, the two friends mentioned their children and reminisced about the good old days, especially de Waele: “Your description of Paul –o that blond Pavlos pictured while plucking the string of the Corinthian guitar, a picture lost with many precious souvenirs in the catastrophe –reminds me of the passing of the years: when we met each other the first time in the Annex, Academy street, we just passed the thirties! What you mention of your children… it shows how much their own life and years have become the measuring rod of our own lives.”

De Waele’s one and only publication about Corinth after 1935, a guide book about the Christian era of Corinth, titled Les antiquités de la Grèce: Corinthe et saint Paul, was published in 1961. Of course, he sent a copy to Broneer. From time to time the two would meet in the Corinthia: “We are still living, Irini and I in the house which once, I remember, you visited. My eldest daughter married to Kostas Lekkas, family of Sophocles, is living here with her two daughters; Joseph is teaching at Ottawa University classical archaeology and my youngest daughter is married to a professor of law at the university of Enschede” (ASCSA Archives, Oscar Broneer Papers, box 24, folder 1, December 17, 1972).

De Waele visited his beloved Corinthia for the last time in the summer of 1977. In November, Jos de Waele, announced his father’s death to Broneer: “He had had a marvelous 3 weeks in Greece and he remembered with great emotion the hours you spent together… I thank you for all the friendship you gave to my beloved father. He spoke to me often of you and I know very well and I know very well, what meant his last encounter with you” (ASCSA Archives, Oscar Broneer Papers, box 24, folder 1, November 9, 1977).

Author’s Note: Telling de Waele’s story was not an easy task. It is common among biographers to empathize with their subject. With de Waele I experienced a full range of emotions, from liking him to disliking him and back to liking him. I would have liked to know what de Waele thought, as an older man, of his doings in 1934-1935. I have the feeling that he never realized their gravity.

References

De Waele, F. 1930. “The Roman Market North of the Temple at Corinth,” AJA 34:4, pp. 432-454.

____________. 1931. “The Greek Stoa North of the Temple at Corinth,” AJA 35:4, pp. 394-423.

____________. 1933. “The Sanctuary of Asklepios and Hygieia at Corinth,” AJA 37:3, pp. 417-451.

____________. 1935. “The Fountain of Lerna and the Early Christain Cemetery at Corinth,” AJA 39:3, pp. 352-359.

Lord, L. E. 1947. A History of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1882-1942, Cambridge, Mass.

*Another Note

In April 2021, Nafsika von Peschke contacted me via e-mail to let me know that the little toddler in the photo with De Waele, which I had originally identified as Paul Broneer, was her. Here is what she wrote me: “I am Nausika von Peschke and I wanted to inform you that the little girl in the picture with Joseph de Waele is not Paul Broneer. It is a picture of me when I was about 3 or 4 years old. I have the same picture. We lived in Old Korinth because my father Georg von Peschke was very involved with the American School and did a lot of work with the excavations. Both my sister Marianna and myself were very close friends with Paul and John Broneer. We lived a couple of blocks from the School in Athens and played together until our teens, until they left Athens. Mrs. Broneer would have wonderful tee parties for us. She was such a lovely lady. Most of the names in your articles bring such great memories.”

Incredible story, Natalia. And I appreciated your personal note about the difficulty of keeping a dispassionate distance from our subject, and this is what all biographers face. Ironically enough, I must have just missed meeting de Waele when he came through Corinth in the summer of 1977. We (Tom Palaima, Gerry Schaus, Margie Miles, Irene Bald Romano) had just finished up the spring excavation season in 1977. However, I do remember Broneer well: he was kind enough to give me some pointers on my School report on the Upper Peirene Fountain on Acrocorinth. The School has an amazing way of drawing us into the lives of our predecessors. As always, Natalia, well told. . .and honest.

Thanks, Glenn, for another supporting note. I am not sure, however, you would have met de Waele at Corinth in 1977, since he was not allowed in the excavation premises.

Good point, Natalia. So, ships passing in the night. Keep up the excellent work. Stay safe.

Another excellent piece Natalia. Thank you. I am afraid the legacy of de Waele lives on in the village. Multiple times over thirty some years in Corinth, over coffee, ouzo, or at gatherings, villagers have told me they assume that all of us at Corinth take home artifacts as a matter of course. I would say my estimate of Mr. de Waele has remained steadfast since I first learned of his suitcase with a false bottom.

Thanks, Paul. A sad story, unfortunately with many repercussions, not just for him….

Very interesting. And sad. Are there any records that mention the specific artifacts De Waele took out of the country without permission and what happened to them? Were they ever repatriated?

Thanks, Kevin. They were not taken out of the country. He was stopped at Customs. I assume that the objects from Corinth were returned to Corinth. The other antiquities, the ones that he purchased, must have ended up at the National Museum (as it happened with the Siphnian herm that Ralph Brewster took out of the country).

Thanks, Kevin. De Waele was stopped at Customs. He was not able to export them. I suppose that the items he removed from the Corinth Excavation were returned to Corinth. As for the purchased antiquities, most likely they ended up at the National Museum (like the Siphnian herm that Brewster took out of the country in 1932).

Very interesting Natalia!

Do you know whether the Broneer papers (or other ‘Greek’ archives) perhaps also contain information about the Nijmegen excavations by de Waele in 1943-44?

Most of the Nijmegen excavation documentation was lost at the end of the Second World War. De Waele probably kept drawings en notes at his house at the Barbarossastraat 1 in Nijmegen, which was destroyed by fire during the battle of Nijmegen (September 17-20 ,1944). De Waele lost 4000 books and was wandering “like a lost sheep” in the halls of Canisius college, where he and his wive, and their children sought refuge. (Diary Sybrand Galama, Monday, September 25,1944)

I find it somewhat strange that in his letter to Broneer (September 9, 1945) de Waele speaks of the war damage in 1944 of Nijmegen “by a British ‘mistake’ that destroyed the heart of the city.”, but not a word about Germans soldiers who in September 1944 had set on fire the Batavierenweg, the Reinaldstraat and partially the Barbarossatraat, including the house of family de Waele…

Perhaps this episode was too painful for de Waele, also because at the time he was accused of collaboration, partly because of his cooperation with the German authorities during the excavations at the Valkhof in Nijmegen. On August 20, 1945 – after been suspended – he had to defend himself for a commission of the Catholic University of Nijmegen. The suspension wasn’t lifted until January 1946. However, De Waele did receive a written reprimand. The university administration stated that De Waele had failed to act appropriately toward the German occupiers, but not so seriously that dismissal was deemed necessary. (Newspaper De Gelderlander, January 10, 1946)

Despite his formal rehabilitation in 1946, he remained suspected of collaboration, probably because of his Flemish nationalist views and his earlier ‘collaboration’ with the Germans as a Flemish student during the First World War. Perhaps this is why the Dutch Internal Security Service (BVD) opened a personal file on de Waele as late as 1949-59.

Dear Arjan, thank you for this interesting (and unknown to me) information. I will check the Broneer papers and get back to you via email.

Thank you! And for your information: the Regionaal Archief Nijmegen has posted several photographs of Ferdinand de Waele and his family in the 1950s en 60s. For example: https://hdl.handle.net/21.12122/342263

Thanks again Arjan. I checked again De Waele’s correspondence with OB but there is no reference to the Nijmegen excavations. In fact, it is the only letter preserved from the 1940s. The next letters are from the 1960s and 1970s. Of course, you know that his wife was Greek and that one of his daughters married a Greek dentist (Lekkas).

Dear Natalia,

I want to thank you again too! Do you know De Waele’s address in his letter of September 9, 1945? His house in Barbarossastraat 1 was destroyed one year earlier… Is it perhaps Graadt van Roggenstraat 26, near his old house in the Barbarossastraat? From 1948 onwards this address is mentioned in address books (Regionaal Archief Nijmegen).

Lindenlaan 10 Kwakkenberg, September 9th, 1945