The Island of Zeus Revisited

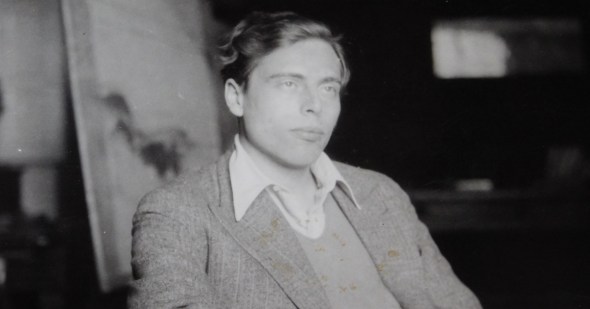

Posted: March 2, 2025 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Crete, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism, Uncategorized, Women's Studies | Tags: Bes-Silenus, Crete, Femicides, Ralph Henry Brewster, Richard B. Seager, Spyridon Marinatos 3 CommentsA few months ago, I was leafing through a special lot of old books that Nick Ervin gifted to the library of the Study Center for East Crete (Pacheia Ammos). One of the books, The Island of Zeus: Wanderings in Crete (London: Duckworth, 1939), caught my eye because I recognized its author: Ralph Brewster (1904-1951). Born in Florence in 1904 to an American father and a German mother, he was fluent in English, German, French, and Italian, and traveled with ease in Europe. I have written about Brewster before (THE LIFE AND TIMES OF A DILETTANTE: RALPH HENRY BREWSTER) when I discovered in the Archives of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA hereafter) that he had been involved in the theft of a hermaic stele from the island of Siphnos in 1932. Georg Karo, the Director of the German Archaeological Institute in Athens, who knew personally Brewster’s family, managed to save Brewster’s skin by coming to “an understanding with the Greek authorities that they would wipe the matter out if the herm could be located and returned” (ASCSA Archives, AdmRec 1001/1, folder 4, Richard Stillwell to Rhys Carpenter, October 2, 1932).

While researching Brewster’s “misdemeanor,” I understood that he left Greece after the theft, not to return since he was unwelcome, and that the subsequent publication of his two books The 6000 Beards of Athos (1935) and The Island of Zeus (1939) were based upon trips he had taken during his time in Greece in 1932. I was wrong. Brewster kept returning until the late 1930s. His many references to Metaxas’s dictatorship in The Island of Zeus date Brewster’s trip to Crete after 1936.

Interested in old ways of land and sea communications, descriptions of landscape and travel distances before modern road construction, and modes of interaction between locals and foreigners, I decided to give it a shot.

Persona non grata?

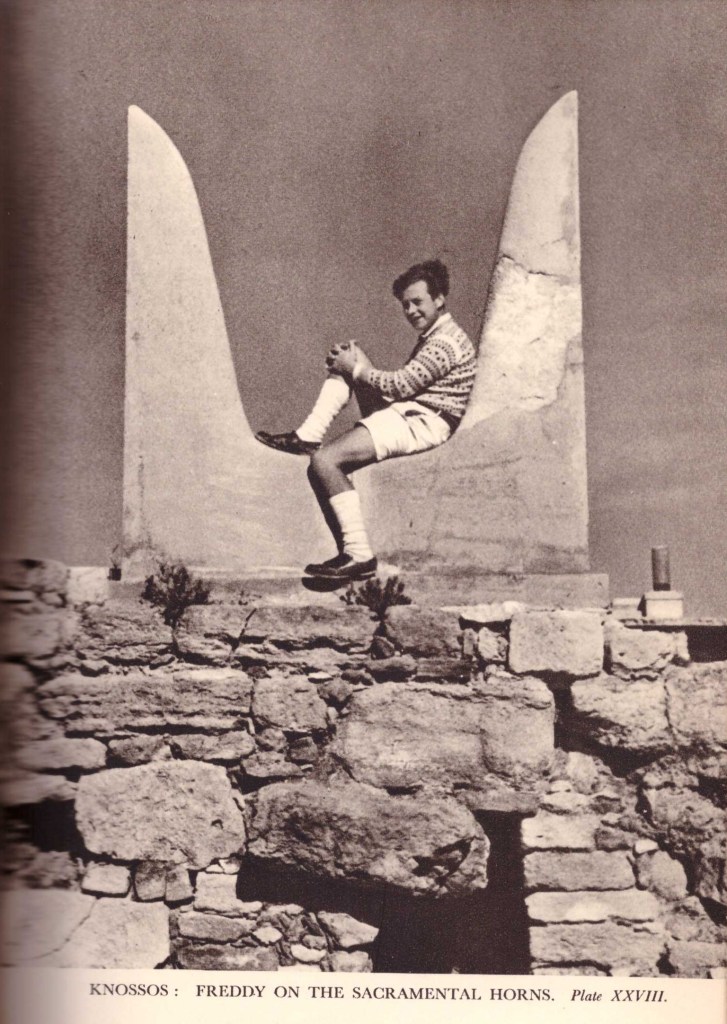

In The Island of Zeus, they travel by a donkey, which was named Minos, and by living in a tent when they do not break into μετόχια. I say “they” because Ralph had a travelling companion, a young Austrian man, Freddy, whom he had met on the island of Corfu. A constant theme in Brewster’s Cretan trip is their lack of money and bad weather. They were traveling in late fall, either of 1936 or 1937. Since the book was published on January 1, 1939, I presume that it was submitted to Duckworth in 1938 at the latest.

In general, Brewster seemed to live by the day. Although from a well-to-do mixed family of English/Austrian origin living in Florence, Brewster seemed to have struggled with money. He delayed his trip to Crete until the fall because his “publishers refused to advance me the necessary funds, yet kept tormenting me with friendly but hurt letters for not having begun the book. […] It is strange that most people -especially the English- are so snobbish that according to them a gentleman must have money, ça va sans dire. If he has not, then he just doesn’t belong, and is not a gentleman. […] Money is sine qua non with them, and as soon as they smell a rat, it’s finished and they either cut you or behave to you like ice” (Island of Zeus, p. 19). At the end of September, with the help of an unnamed friend, Brewster managed to retrieve his cameras from the pawnbrokers in London, buy films, and a ticket as far as Corfu where he met his family. With a little more help from his mother, he bought the tent and the boat tickets to Athens and Crete.

While in Athens he obtained a letter of recommendation to all Greek authorities from the Ministry of Education which allowed him to photograph antiquities. Brewster preferred to use that document when asked for his passport by the Greek authorities. He would even get into a fights rather than present his passport to the police. Brewster blamed the dictatorship of Metaxas for the police’s insistence; this happened in almost every town or village they went, and almost every time Ralph fought it. Was he just obnoxious or afraid that his name might ring a bell?

Three Nights in Anogeia

Ralph and Freddy’s original plan was to explore Crete economically living in the tent. A recurrent theme in the book is their penniless situation, with Ralph waiting for wired money either from his publisher or his mother. Instead of being an asset, the tent soon became a burden. “Our tent is most unsatisfactory. It has no floor, so everything inside is covered with dust and dirt.” But their biggest problem was an unprecedented storm that hit Herakleion and forced them move with all their belongings into the Hotel Palace, borrowing from the proprietor four hundred drachmas on the strength of their luggage. “Since four o’clock in the afternoon the rain has been coming down with unprecedented violence. It is really like the great deluge in the bible. The streets have turned into rivers […]. The electric light has gone out, and there are no candles in the hotel” (Island of Zeus, p. 22-23). The next day they found that one quarter of the city had completely flooded, houses were destroyed, and many people were drowned. As for their tent, “it had been carried off into the sea.” They retrieved it the following day: “a large muddy bundle […] some fishermen had found it on the beach a couple of miles further on, where it had been washed by the waves” (Island of Zeus, p. 25). After paying a reward of three hundred drachmas, they happily went on to wash and dry the tent.

Having paid their debts in Herakleion (Ralph had received a check of five pounds from his mother), they headed toward Mount Ida. They spent the night in the village of Anogeia in the house of a family that Ralph had met in Herakleion. They entered the house through a small forecourt leading to an oblong kitchen-living-room where several people were seated round a corner fire-place (Island of Zeus, p. 30). Ralph went on to describe about ten relatives of all ages in the room. Soon they were drinking “Tsikoudhia” with almonds. “We had to drink it down with a smile, although intensely disliking it. It burned the throat and tasted of aniseed though made of raisins” (Island of Zeus, p. 31).

The moment they retired to their bedroom, “a nice room with hand-woven colored kerchiefs hanging from pegs on the walls,” on the first floor of the house, “one by one the entire party from downstairs came up to see us settled, and the room was soon packed. We were obliged to have another round of Tsikoudhia.” In the middle of the night, both Freddy and Ralph experienced tummy-aches from the food they had eaten. Their visits to the shed outside the house held more surprises: “The floor with the important hole was lop-sided and disconcerting and I was startled by alarming noises coming from underneath the hole. It was the grunting of pigs who were scuffling about underneath” (Island of Zeus, p. 32).

For breakfast they were brought Turkish coffee, dried crusts, and raisins. “And soon, one by one, the various members of the family came in and sat down” with them. Their breakfast was interrupted by the police who wanted to check their passports. “Yes, things seem to have changed a lot in Greece since last year!” I said handing the passports to our host. “And how!” he sighed, and everybody turned round and looked up mournfully at the photograph of Venizelos on the wall. “Poor old dear!” the father said in a quivering voice. “He was a great man! He has left us now!” (Island of Zeus, p. 33).

Because of the rainy weather Ralph and Freddy were forced to extend their stay at Anogeia for another day. Their lunch consisted of roast mutton and some vegetable. Once again, only the host ate with them. In the evening, to reciprocate the hospitality, they treated their hosts with hot chocolate that they cooked on their Primus, a camping stove. “It was appreciated as a change from the usual Tsikoudhia” (Island of Zeus, p. 34). Finally, after three days at Anogeia, the rain stopped and the two men got ready to leave. The Cretan family insisted on being photographed. “They all put on their national costumes, which the women wear nowadays only on feast-days, and stood stiffly in a row […]. Only little Marika was not self-conscious and stiff during this absurd performance” (Island of Zeus, p. 35). And it was sweet, little Marika’s photo that Ralph chose to include in The Island of Zeus (pp. 32-33).

Chania more Charming than Candia

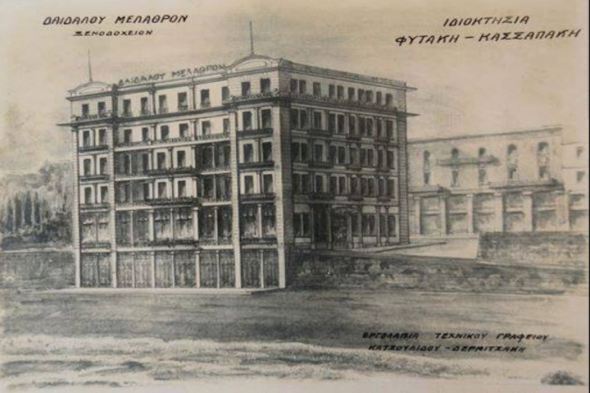

Of the two Cretan cities, Brewster found Chania more charming, mainly because the destruction of the Venetian and Ottoman buildings was not as widespread as in Herakleion (Candia). Ralph was also disappointed by the lack of life in the harbor: “here in Candia the water-front is dead -almost sinister.” The modern harbor was even more depressing than the inner one (the Venetian), “for its chief feature is a monstrous seven-storied building whose pretentiousness crushes everything within sight” (Island of Zeus, p. 16). Ralph was referring to the newly constructed Μέγαρον Φυτάκη, the pride of Herakleion. It was the first multi-storied building to be constructed in the city in the late 1920s, and the center of local life until WW II. There were 26 residential apartments in the upper floors while the lower floors were occupied by various offices including the Theotokopoulos Club of Scientists (Λέσχη Επιστημόνων Ηρακλείου). (After decades of decline, the Μέγαρον Φυτάκη was renovated and transformed into a five-star hotel, the GDM Megaron, in the 2000s.)

Ralph did not have anything good to say about the Herakleion Museum either. “Everything is crammed into three rooms, while a new museum is being built.” He found the restoration of the Minoan frescoes “most horribly.” “But the vases, statuettes, bronze objects, and jewels are very beautiful…” (Island of Zeus, p. 24).

He didn’t mince his words for St. Mark’s church and the Morozini Fountain. And rightly so, for the church had been turned into a cinema. It was playing Anna Karenina with Greta Garbo during Ralph’s staying in Herakleion. He was pessimistic about the future of the Morozini fountain and said he would not be surprised if the Venetian fountain was removed one day and the sculptures chopped up and used as building material.” His comments may sound strange today but one is reminded that the Cretans destroyed the Venetian Loggia in one night in 1904, and in the 1970s they demolished the large church of San Salvador without remorse. When Ralph complained about the ruinous condition of the Loggia to the German wife of a Greek doctor, she said: “But the Greeks are quite right. They cannot bear to be reminded of the days in which they lived under a foreign yoke, and quite justly systematically destroy everything which was constructed by foreigners” (Island of Zeus, p. 109). It is true. It would take at least three generations in the Νέαι Χώραι (Macedonia and Crete) and the Dodecanese before people felt comfortable with their cities’ “other” past.

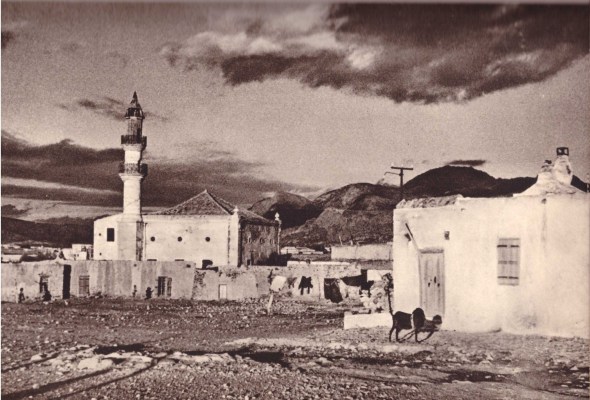

Looking for the local museum in Ierapetra, Ralph was pleased to see that the adjacent mosque had escaped demolition or change of use. “It [the museum] was on the western outskirts of the town inside the first-aid station, a simple one-storied building near a crumbling mosque with a minaret which had been overlooked by the ravaging patriots of modern Greece. Next to it was a charming Turkish fountain, surmounted by a small dome, But since the Turks have gone, water no longer flows from it” (Island of Zeus, p. 243). Built as late as 1891, the mosque served the local Muslims for a short period only. After the declaration of Crete as an autonomous state (Κρητική Πολιτεία) in 1898 and its later unification with Greece in 1908, many Cretan Muslims (Τουρκοκρητικοί) left the island in search of safer lands.

Seager’s House

On their way to East Crete, Ralph and Freddy stopped at the village of Pacheia Ammos where Richard B. Seager (1882-1925), the excavator of Pseira and Mochlos, had built his house in 1906. After Seager’s death in 1925, the house had passed on to his foreman, Nikolaos Sareidakis (Marshall and Betancourt 1997, p. 183). The house had been turned into a pension where the two men were hoping to find shelter. Unfortunately, they found it all closed. Ralph must have visited it before because he remembered “how delightful the courtyard was, full of luxurious plants and flowers, beautifully paved with pebbles, and with a well in the center. A portico ran round three sides and many huge earthenware pots reminded you of the Minoan jars in Knossos and Phaistos. Most of the bedrooms looked out to the sea and the mountains, but to pass from one room to another you had to enter the cloister. There was something magic about this courtyard, which enchanted you every time you stepped into it.”

The Seager house still remains privately owned. We managed to get a small tour of its interior by its current owners about fifteen years ago. (The photos above were taken by Jack L. Davis in 2012.)

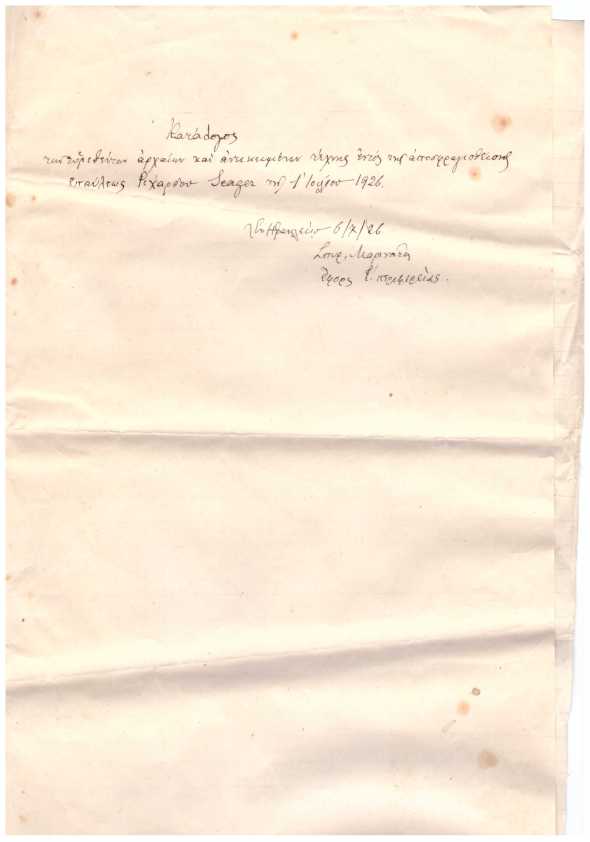

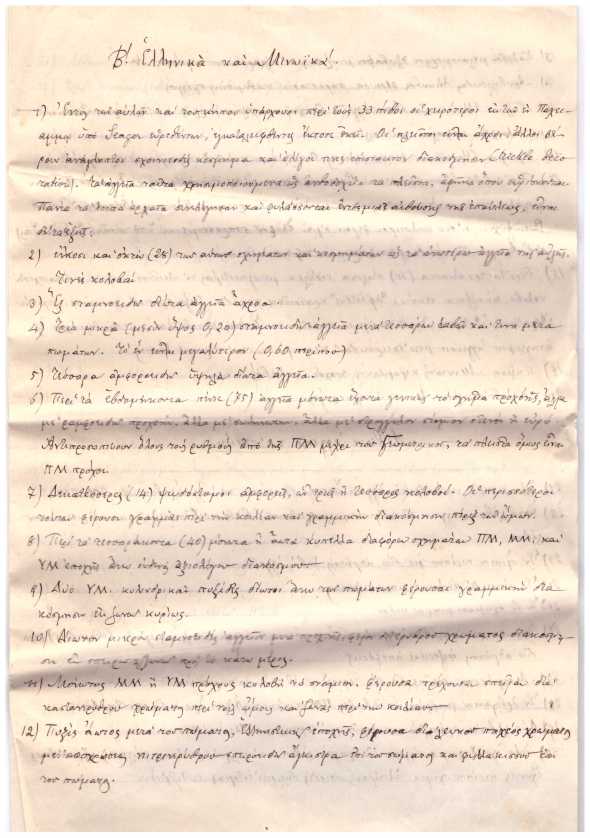

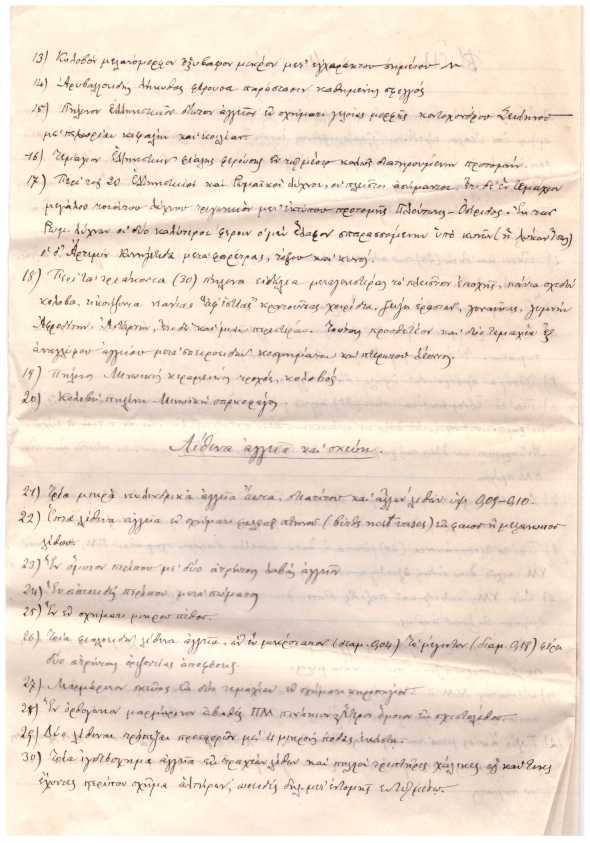

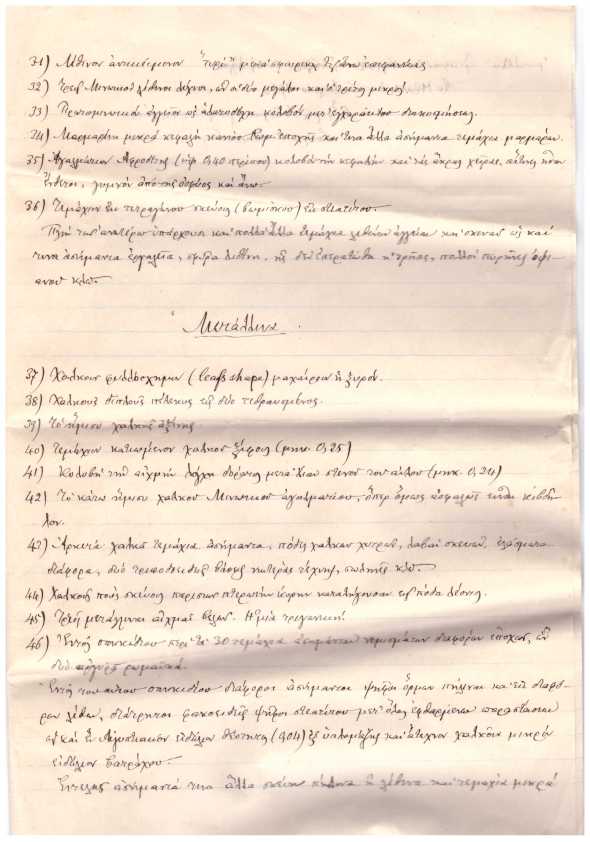

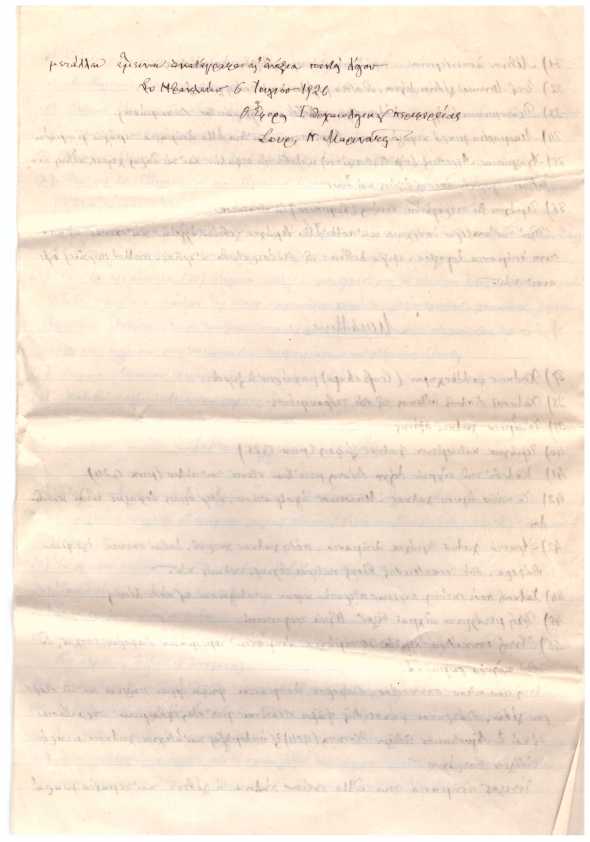

In the Spyridon Marinatos Papers in the ASCSA Archives, there is the report that young Marinatos submitted in July 1926 to the Ephor Stephanos Xanthoudides recording the objects, modern and ancient, that were found in the Seager House after its owner’s unexpected death.

Marinatos’s report includes the following object (no. 15): «Πήλινον ελληνιστικών [χρόνων] δίωτον αγγείον εν σχήματι γελοίας μορφής κοντοχόνδρου Σειληνού με πελωρίαν κεφαλήν και κοιλίαν». In 2016, for Stella Drougou’s Festschrift titled Ηχάδιν, I published such a vessel of unknown provenance in the Ierapetra Archaeological Collection (Vogeikoff-Brogan 2016). Could it be identified with the vase that Marinatos found in Seager’s house? I am almost certain that it is! (Use the slider below to see both the Silenus vase in the Ierapetra Collection and the Marinatos report.)

Femicides: Once Justified as Honor Killings

There was a story in Brewster’s book that left me gasping. While travelling in West Crete, Ralph spent a few days at the village of Elos near Chania. There he met a Nikolis Ziakis, “the man who chopped his three sisters into pieces with a knife.” Brewster heard the story from Nikolis himself.

Ten years earlier, Nikolis had been forced to immigrate to South America in order to support his mother and three sisters who worked on the property of a rich landowner. “They looked after his herds and collected his olives and chestnuts.” While in South America, Nikolis was frequently rebuked by his relatives who kept nagging him to come back to watch his sisters. After having saved enough money, Nikolis decided to return home. “Nobody knew I was coming.” His homecoming was not met with enthusiasm. His mother and sisters were nervous. At the local café, “all my old friends with whom I used to be inseparable appeared now cold towards me. The only questions they asked were about my two youngest sisters.”

When Nikolis demanded that his two sisters return home, his mother resisted, and the sisters delayed as much as they could. “They were obviously hiding something from me, but I could not make out what it was.” Finally, one of the villagers shouted at Nikolis: “You fool!” Haven’t you yet understood that nobody in the village here wants to have anything to do with you? You have made a fool of yourself, not only you but your whole family has.”

Finding out that one of his sisters was pregnant, he decided to cleanse his lost honor by killing all three of them:

“I went on hitting Arkhonto with my knife, and when I had done with her, I began with Dhéspoina. I don’t know how many thrusts I gave each of them.” Then he ran after his other sister, Katerina, and their mother. “I ran after them and caught Katerina under a plane tree, and there I thrust my knife into her again and again until she was dead.” When Ralph asked him if he regretted his actions, Nikolis answered: “Not in the least, but annoyed at not having been able to kill my mother too” (Island of Zeus, pp. 57-62).

After the murders, Nikοlis surrendered at the police. He was sentenced to two and a half years. But by serving his sentence in “a severer prison, where one days counts as much as two in a normal prison,” he was let out after a year and a half!

Nikolis had killed three women and an unborn baby, and the court had sentenced him to two and a half years! What happened in a remote village of Crete in the 1930s was, however, neither unique nor local. Until 1974, “it was the law in Texas that homicide was justified -not a criminal act, and therefore subject to no penalty whatever- when committed by the husband upon the person of anyone taken in the act of adultery with the wife…” (Wilson and Daly, 1992, p. 84).

The term femicide was first coined in 1976 by South African activist Diana E.H. Russel (1938-2020) in an effort to define men’s license to kill their wives, sisters, daughters, mothers even, and to be excused by the judicial system. The term was adopted in a worldwide level in 1992 following the publication of Femicide: The Politics of Woman Killing by Jill Radford and Russell as co-author.

A Lukewarm Reception

The book received lukewarm reviews. Brewster was praised for his photography and certain parts of the narrative -reviewers found Freddy’s personality and adventures charming- and his gift for retelling people’s stories. British classicist H.D.F. Kitto, for example, found the author’s complaints about the weather and his lack of money boring and uninteresting (The Classical Review 53:5/6, 1939, p. 226).

The most sympathetic review came from The Guardian: “The book is full of good things, ancient and modern. It a relief to know that Mr. Brewster, the humorous archaeologist, has survived all the perils by which he was surrounded, and we look forward eagerly to his next expedition. If there is any justice in this world he will sally forth, as one result of this book, with such a comfortable balance at the bank that he will no longer have to resort to desperate expedients” (23/6/1939, p. 7).

Even if he made any money from the book sales, it was soon without value because of the war. He found himself hiding in Budapest since neither of his two citizenships (Austrian and Italian) served him well. Brewster died of a heart attack in 1951 at the age of forty-five. His last book Wrong Passport, published posthumously (1955), is about his adventures during WW II.

References

Becker, M. J. and P. P. Betancourt, 1997. Richard Berry Seager : Pioneer Archaeologist and Proper Gentleman, Philadelphia.

Vogeikoff-Brogan, N. 2016. “A Bes-Silenus Plastic Vase in the Ierapetra Archaeological Collection: The Egyptian Connection,” in Ηχάδιν: Τιμητικός τόμος για τη Στέλλα Δρούγου, ed. M. Giannopoulou and C. Kallini, Athens 2016, pp. 808-822.

Wilson, M. and M. Daly, 1992. “Till Death Do Us Part,” in Femicide: The Politics of Woman Killing, ed. Jill Radford and Diana E. H. Russell, New York 1992, pp. 83-98.