Grace Macurdy of Vassar College: Scholar, Teacher, and Proto-Feminist

Posted: September 1, 2017 | Author: Natalia Vogeikoff-Brogan | Filed under: Archival Research, Biography, Book Reviews, Classics, History of Archaeology, Women's Studies | Tags: Abby Leach, Barbara McManus, Grace Macurdy, J. A. K. Thomson, Robert L. Pounder, Vassar College |1 CommentThis is a guest post by Robert L. Pounder

Robert L. Pounder, Emeritus Professor of Classics at Vassar College, here contributes a review of Barbara McManus’s posthumous book about Grace Harriet Macurdy, titled The Drunken Duchess of Vassar. Pounder, who has been conducting in-depth research on the social history of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA) in the 1920s-1930s, writes that Classics was “dominated by unaware, myopic, smug, unsympathetic men, men who viewed academic accomplishment by women with condescension and skepticism.” Women in academia, like Macurdy, were thought to be anomalies–a different species. Based on his work at the ASCSA Archives, Pounder has also published an essay, “The Blegens and the Hills: A Family Affair,” in Carl W. Blegen: Personal & Archaeological Narratives, ed. N. Vogeikoff-Brogan, J. L. Davis, and V. Florou, Atlanta 2015.

Born in 1866 in Robbinston, Maine, Grace Harriet Macurdy was the sixth of nine siblings whose parents had immigrated to the United States from the nearby Canadian province of New Brunswick just a year before her birth. Her father, Angus McCurdy (the spelling of the name was later changed to Macurdy because he did not want to be thought Irish) was a carpenter who barely eked out a living. After leaving his children in the care of their mother and paternal grandmother for long periods and thus improving his situation somewhat, he was able to move the family to Watertown, Massachusetts by 1870; there they grew. Watertown provided a better series of houses and slightly improved material circumstances for the Macurdy children. Moreover, they profited greatly from the guidance of their mother and grandmother, both of whom encouraged the children, including the girls, to read, write, and pursue their educations.

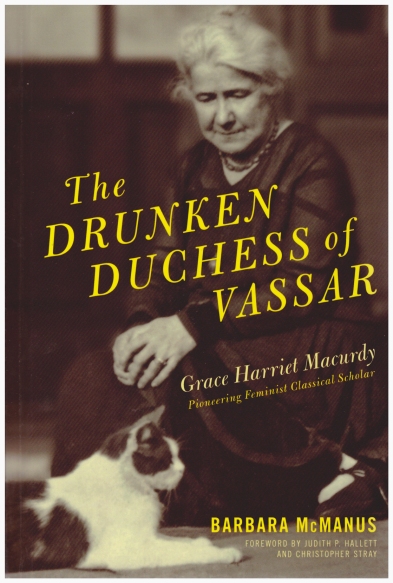

Barbara McManus, The Drunken Duchess of Vassar, Columbus: The Ohio State University Press (2017).

There arose from this unlikely beginning one of the most distinguished, if not suitably recognized, American classicists of the 20th century. The life of this scholar and teacher forms the inspiration for an exemplary biography by the late Barbara McManus, herself an important classicist. McManus has composed a study of Grace Macurdy’s life and career that enriches our knowledge of the history of classical scholarship in America and Great Britain. It also broadens our understanding of the social contexts that shaped the study and teaching of Greek and Roman antiquity in the early 20th century, shedding fresh light on the challenges that women scholars faced in order to be taken seriously in a field dominated by unaware, myopic, smug, unsympathetic men, men who viewed academic accomplishment by women with condescension and skepticism. The relative obscurity of Grace Macurdy today, even among scholars in her field, attests to the long and rocky road that women scholars had to follow in the 20th century – in the U.S., England, and Europe alike – with no guarantee that excellence and innovation would be rewarded or even noticed. McManus addresses this issue head-on, pointing out that, even into the 20th century, women scholars were viewed by the academic establishment as anomalies, even as oddities, a different species, weaker personages who tried but could not equal the intellectual achievements of men. To illustrate: when a Festschrift comprising twenty-two articles was published to honor Macurdy’s dear friend, the British classicist Gilbert Murray (who claimed to admire her work), every one of the twenty-two authors was a man (Greek Poetry and Life, Essays Presented to Gilbert Murray On His Seventieth Birthday, 1936). These men believed that the natural state of women was as wives and mothers, not as leaders in business or politics or the academy. This state of affairs had grown out of 19th- century attitudes, and it would take many decades, into the 1970s and the women’s movement, for the foundations of such beliefs to start crumbling, a process that has not ended but continues to this day.

Grace Macurdy (1866-1946) showed promise from her childhood years onward. By 1879 she had advanced in her studies to the point where she could enroll in Watertown High School’s college-preparatory course. There she studied English, French, history, mathematics, chemistry, physics, and – significantly – Greek and Latin, in which last subjects she particularly excelled. The next step was application to the “Harvard Annex” – renamed Radcliffe College in 1894 – a private program that offered women instruction, by Harvard professors, equivalent to that received by men at Harvard College. In 1884, after three days of Harvard entrance examinations, she passed without any conditions, achieving honors in classics. Grace entered the Annex in September 1884. Her performance placed her at the top of her class. As McManus points out, Macurdy did not share the ambitions of most of her fellow students, who aspired to teaching positions in New England schools: “She was determined to win recognition as a classical scholar with a professional career like her Harvard mentors.” And she miraculously did not suffer the pangs of uncertainty and self-doubt – engendered by ambivalent attitudes of many of the Harvard professors toward the higher education of women — that afflicted many of her friends. Helen A. Stuart, class of 1891, wrote to a friend:

It was always impressed upon us that we must be inconspicuous, and must never cross the Harvard Yard, unless we were attending some special lecture or reading…As to the relations between Harvard and the Annex, it was borne in upon us very frequently that the University as a whole scorned us, and only the broad-minded professors were really interested in our success. The students in general thought of us as unattractive bluestockings and compared us unfavorably with the Wellesley girls.

Ironically, McManus observes, Grace Macurdy’s working-class background helped her to conquer this sort of self-doubt and ambivalence. Her family had to scrimp and save, and they lacked the niceties of life, including social status and interactions, except within their modest circle. Grace “could not afford ambivalence,” since “success was her only option.” In 1893 she was hired by Professor Abby Leach to teach in the Greek department at Vassar College.

Abby Leach (1855-1918).

Thus began the remarkable career of Grace Macurdy as scholar, teacher, and proto-feminist. Her charismatic personality and sparkling intelligence captivated students, bringing her popularity within the Vassar community. Abigail (Abby) Leach, a formidable figure who had been the initiating force behind the establishment of the Harvard Annex, was revered by Macurdy, but not to the same degree by students, many of whom found her an uninspired, rote teacher. One of them, Margaret Shipp, Vassar 1905, wrote home: “Miss Leach may know a lot and be very famous, but she is absolutely the most uninteresting instructor I ever came across… She is about as flexible as a wooden post.” But Leach was a formidable figure at Vassar.

Hired in 1883, she had singlehandedly built up the Greek department, an offshoot of the former Department of Ancient Languages, and after having taught many Latin courses for several years, by 1886 was in charge of all the courses in Greek, now a separate department, “my” department, as she referred to it in an early conversation with Macurdy. Upon her arrival, Macurdy was given the freshman and sophomore Greek courses to handle, though the upper level work was reserved for Professor Leach (who did not like to be referred to as “Miss”). At first, Abby Leach offered strong support to Macurdy, urging her to take a year off to study in Berlin and elsewhere in 1899-1900. Upon her return, Macurdy was advised by Leach to enroll in the doctoral program at Columbia. There she spent two highly productive years that produced a dissertation on the chronology of the plays of Euripides, and her PhD was conferred in 1903; Vassar immediately promoted her to associate professor of Greek.

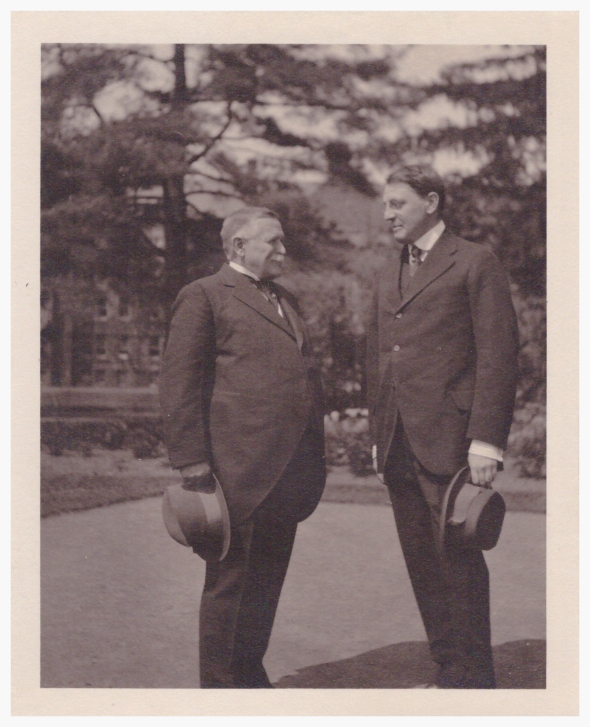

With clarity and precision, Barbara McManus presents the story of the conflict between Leach and Macurdy that began soon after Macurdy’s return to teaching. Alarmed by Macurdy’s growing popularity in the classroom and by the recognition she was receiving outside the walls of Vassar, Leach invented numerous excuses to hold her back and prevent her from teaching advanced courses. She dreamed up dubious charges of poor or negligent teaching. It was a classic case of jealousy and envy. Leach felt threatened: Greek was her department, and an upstart was undermining her authority, or so she thought. In 1907 she recommended that Macurdy be fired. The Vassar president, James Monroe Taylor, was drawn into the battle,which was waged for another decade, and so were the Committee on Faculty and Studies of the Board of Trustees and the next president, Henry Noble MacCracken. Despite the angry opposition of Leach, Macurdy’s demonstrated achievements resulted in several reappointments in this period, which came to an end only with Abby Leach’s death in 1918.

James Monroe Taylor and Henry Noble MacCracken, Presidents of Vassar College, 1915. Source: ASCSA Archives, Ida Thallon Hill Papers.

As the years went on, Grace Macurdy’s career blossomed. As was mentioned above, she became a good friend of the Oxford classicist Gilbert Murray and his wife. She also entered into a friendship with another British classicist, J.A.K. Thomson, with whom she corresponded and traveled. The relationship with Thomson was close but probably not a conventionally romantic one; rather it was borne of deep and sympathetic intellectual affinity. Thomson, thirteen years her junior, a King’s College, London classicist with Marxist leanings, translator of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics and author of popularizing works such as The Classical Background of English Literature, probably clicked with Macurdy in part because of shared leftist politics. Both Murray and Thomson became important soulmates for Macurdy, forming a sort of family for her in England.

Barbara McManus (1942-2015)

Macurdy became the Vassar representative on the Managing Committee of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (although she had not studied at the School). In that capacity she was drawn into the feud between the director, Bert Hodge Hill, and the chair of the Managing Committee, Edward Capps, a battle that was waged in the mid-1920s and ended with the dismissal of Hill, who had been director since 1906. Macurdy fought on the side of Hill and his wife Ida Thallon Hill (Vassar 1897), her former student and now intimate friend, and bravely spoke out in Managing Committee meetings against the campaign to impugn Hill and his directorship. The quarrel had grown out of Capps’s irritation with Hill’s slowness to publish assigned material from Corinth and the Athenian acropolis as well as his failure to provide timely reports to the Managing Committee about School excavations and activities, reports that were needed for Capps’s growing fundraising initiatives. A triumph of Barbara McManus’s biography is her masterly analysis of the voluminous materials that document the Capps vendetta. Housed in the American School archives, these letters, cables, copies of petitions, memoranda, official minutes and reports, and other documents present challenges to anyone attempting to make sense of the twists and turns of what happened. McManus gives us a clear interpretation, and she also corrects mistakes present in earlier publications. Her achievement in writing about the Women’s Hostel controversy at the American School – it ended with the construction of Loring Hall, a residence for both sexes – is equally impressive. Her scholarly method is meticulous and exhaustive, the results always easy to follow (see also N. Vogeikoff-Brogan, “Clash of the Titans: The Controversy Behind Loring Hall“). The premature death of this scholar is a blow to classical scholarship; her quiet role in the advancement of classical studies is now seen as an essential one, too soon ended.

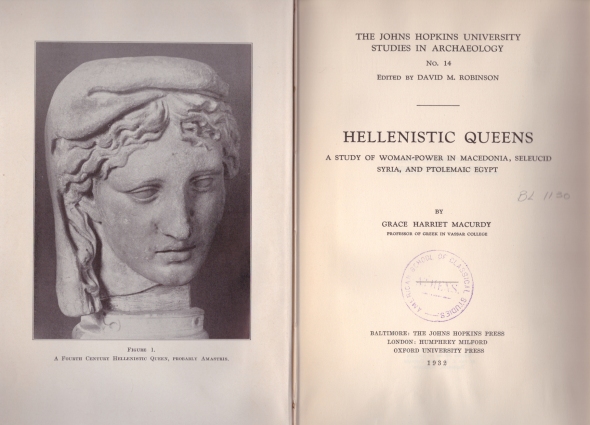

The life of Grace Macurdy had its share of heartbreak and misfortune. A mysterious ailment caused the loss of most of her hearing in both ears in the early 1920s. This disability she managed to deal with, using ear trumpets and other methods, until her death. The deaths of family members over the years brought sadness, but this remarkably chipper, wry woman surmounted all obstacles to happiness and serenity. Her books, Hellenistic Queens: A Study of Woman-Power in Macedonia, Seleucid Syria, and Ptolemaic Egypt (1932) and Vassal-Queens and Some Contemporary Women in the Roman Empire (1937) were met with appreciative and, in a few instances, glowing reviews (though there was a tendency among her fellow ancient historians to regard powerful women in the Hellenistic and Roman Mediterranean as tangential figures, scarcely worthy of serious study). Her final book, The Quality of Mercy: The Gentler Virtues in Greek Literature (1940) returned her to the literary roots of her dissertation. Following her retirement from Vassar in 1937, Macurdy continued to write and to play an active role in such institutions as the American School of Classical Studies. As her health declined, life became more difficult, especially owing to a deterioration in her sight that a costly and difficult eye operation failed to cure. She died in Poughkeepsie in 1946.

One of Grace Macurdy’s books. ASCSA, Blegen Library.

Barbara McManus has unearthed unexpected and intriguing nuggets about Macurdy. For instance, although her immediate background was working-class, her ancestors in Canada and the United States included many eminences; indeed, she was a distant relative of both Winston Churchill and Franklin Delano Roosevelt (an appendix provides her family tree). She herself formed some surprising friendships, such as those with the novelist John Galsworthy and the poet John Masefield, men who were drawn to her charm and magnetic intelligence. Only now is her importance coming to the fore, and we have McManus to thank for that. A final quibble: the title of the biography seems off-base to me. An affectionate nickname applied to the teetotaling Macurdy by her adoring students — who were bent on capturing her whimsical eccentricity – the flippant term “drunken duchess” undermines the seriousness of the biographical subject. Fortunately, it cannot undermine the laudable achievement of the biographer.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

Related

One Comment on “Grace Macurdy of Vassar College: Scholar, Teacher, and Proto-Feminist”

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Great review, Bob! I agree with you about the poorly-chosen title.