At Home with the Schliemanns: The “Iliou Melathron” as a Social Landmark

Posted: January 6, 2022 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Arts and Crafts Movement, Biography, History of Archaeology, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism, Women's Studies | Tags: Charles Wesley Bradley, Ernst Ziller, Heinrich Schliemann, Iliou Melathron, Sophia Schliemann 8 CommentsHeinrich Schliemann, the famous excavator of Troy, Mycenae, and other Homeric sites, was born in Germany on January 6, 1822–the Epiphany for western Europe and Christmas Day for other countries such as Imperial Russia and Greece which still used the Old (Julian) Calendar until the early 20th century. A compulsive traveler, Schliemann rarely returned to Athens before late December or early January, just in time to celebrate both his birthday and Christmas on January 6th.

From today and throughout 2022, many institutions in Europe, especially in Germany but also in Greece, will be commemorating the bicentennial anniversary of his birth. The Museum of Prehistory and Early History of the National Museums in Berlin is preparing a major exhibition titled Schliemann’s Worlds, which is scheduled to open in April 2022. Major German newspapers and TV channels are in the process of producing (or have already produced) lengthy articles and documentaries about Schliemann and his excavations at Troy in anticipation of the bicentennial anniversary, and Antike Welt has published a separate issue, edited by Leoni Hellmayr, with eleven essays about various aspects of Schliemann’s adventurous life.

The American School of Classical Studies at Athens, where Heinrich’s and Sophia’s papers have been housed since 1936, in addition to contributing to all the activities described above, will be launching an online exhibition, The Stuff of Legend: Heinrich Schliemann’s Life and Work, on February 3, 2022, showcasing material from the rich Schliemann archive.

According to Ernst Ziller, the architect of the Iliou Melathron, Heinrich Schliemann’s only request from him was that Ziller build him a large house within which to live and entertain. And indeed, Heinrich and Sophia’s spectacular balls were described in detail in the local newspapers. Heinrich, however, was a husband-in-absentia, spending not more than four or five months a year in town. During his absence, Sophia had to turn this museum-looking house into an agreeable and comfortable space for her and their two children. Following Schliemann’s death in 1890, she continued to entertain lavishly, thus making an invitation to the Iliou Melathron a coveted item among the locals and foreigners who lived in late 19th/early 20th century Athens.

“Few people, save Greeks, know that modern Athens is in reality two cities, each differing from the other in climate, in traditions, and to a great extent, in character of population.” These are the opening lines in George Horton’s Modern Athens. He goes on to describe his favorite of the two cities: “Winter Athens, roughly speaking, is the resort of tourists, diplomats, and climate-seekers. It is a European city where one eats course dinners at the Angleterre Hotel, attends service at the English Church, dances the barn dance at Madame Schliemann’s and plays charades in the library of the American School.” Horton (1859-1945), a distinguished diplomat and a literary figure, published Modern Athens in 1902. In it he described his experiences in the city during the five years he served as US Consul (1893-1898).

Balls and evenings at “Madame Schliemann’s” are also frequently described in letters and diaries of students and members of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (American School or ASCSA hereafter). Ever since its first inaugural ball in January 1881, the Iliou Melathron had remained a prominent landmark in the social life of high-society Athens. By then Heinrich was no longer an unknown wealthy merchant, who had landed in Athens eleven years earlier to marry a young Greek woman, Sophia Engastromenou, and start a new life in Greece. While the couple’s first house on Mousson Street (today Karagiorgi Servias – Καραγιώργη Σερβίας), near Constitution Square, might have sufficed for the early stages of their Athenian adventure, the arrival of children (Andromache and Agamemnon), an ever-increasing collection of books and antiquities, and, above all, his growing fame as the excavator of major archaeological sites, demanded an upgrade in the couple’s lifestyle.

George Korres and others, including more recently Umberto Pappalardo, have written extensively about the architecture and elaborate decoration of the Iliou Melathron. Here I am interested in the Iliou Melathron as a cultural object and a place “to express feelings, ways of thinking and social processes, and to provide arenas for culturally defined activity,” according to Robert M. Rakoff’s definition.

The Inaugural Ball

The inaugural ball given by the Schliemanns at their new house on January 30, 1881 was described in great detail in the social section of the Greek newspaper ΜΗ ΧΑΝΕΣΑΙ. The author of the essay (signing as Viriloque) was impressed by the harmonious balance in the choice of guests: members of the diplomatic corps, the Phanariots (prominent Greek families originally from Constantinople who played a leading role in the Greek War of Independence), the Greek diaspora (Greeks living abroad), and, naturally, those from the upper echelons of Athenian society. And while at other Athenian soirées, there was a recognized hierarchy in the reception of these four groups, Sophia distinguished herself by entertaining her guests with equal grace. Dressed in black and wearing a necklace made from beads found in an ancient grave, Sophia offered tours to guests who were interested in the ancient vases, inscriptions, and statues that Schliemann had gathered on the second floor of the house. On the first floor, Schliemann conversed with diplomats, including the German ambassador Joseph von Radowitz (1839-1912), who was among the most knowledgeable Europeans on Balkan matters. And while in the past Schliemann ended his evening balls by midnight so that he would not miss his daily 5am swim at Phaleron, that night under Sophia’s influence he agreed to extend the party until 3am and thus miss his morning ritual.

Lynn and Gray Poole in their book One Passion, Two Loves: The Schliemanns of Troy also described with poetic license the grand opening of the Iliou Melathron:

A great procession of carriages rolled up to Iliou Melathron, carrying the fashionable society of Athens and the Continent through the entrance gates, which were attended by the gateman Bellerophon, who was proud of the ancient name given him by Heinrich… From the entrance vestibule the guests stepped into the large vestibule, where they were welcomed by Heinrich and Sophia. Eagerly they entered the Great Hall and wandered through the house, admiring its splendours. Men who normally walked erect moved their heads down, marveling at the mosaics underfoot. Ladies who usually coquetted with eyes cast down gazed at the murals overhead. Even the most sophisticated inspected in wonderment the house that was indeed a palace.

Then the Pooles go on to describe at length an anecdotal event that supposedly happened that night. Since their book lacks footnotes, the source of their description is unclear. Were they drawing from a local newspaper, a document from the vast Schliemann archive, or were they simply recording the memoirs of Sophia’s only living grandchild, Alex Melas, who had invited them in 1963 to write a new book about his famous grandparents?

According to their narrative, the day after the inaugural ball, Schliemann received a document “bearing the official seal of the Council of Ministers” demanding that Schliemann remove or cover the naked statues on the rooftop balustrade of Iliou Melathron. It was Sophia who found the solution, hiring an army of seamstresses to make clothes for the statues. The next morning Athenians en route to work were stunned to see the statues “dressed in flowing garments of gaudy cloth, the most unattractive and garish that Heinrich and Sophia could find.” In addition, Schliemann was spreading rumors that the Greek State had ordered him to clothe the statues. “The Greek Ministers… dispatched a messenger to Schliemann shortly before noon” begging him “to remove the garments from the statues in order that business in Athens return to normal. With great glee, Heinrich mounted to the roof, and in full sight of the crowd below, ostentatiously and dramatically removed each garment, waving it triumphantly before going on the next statue.”

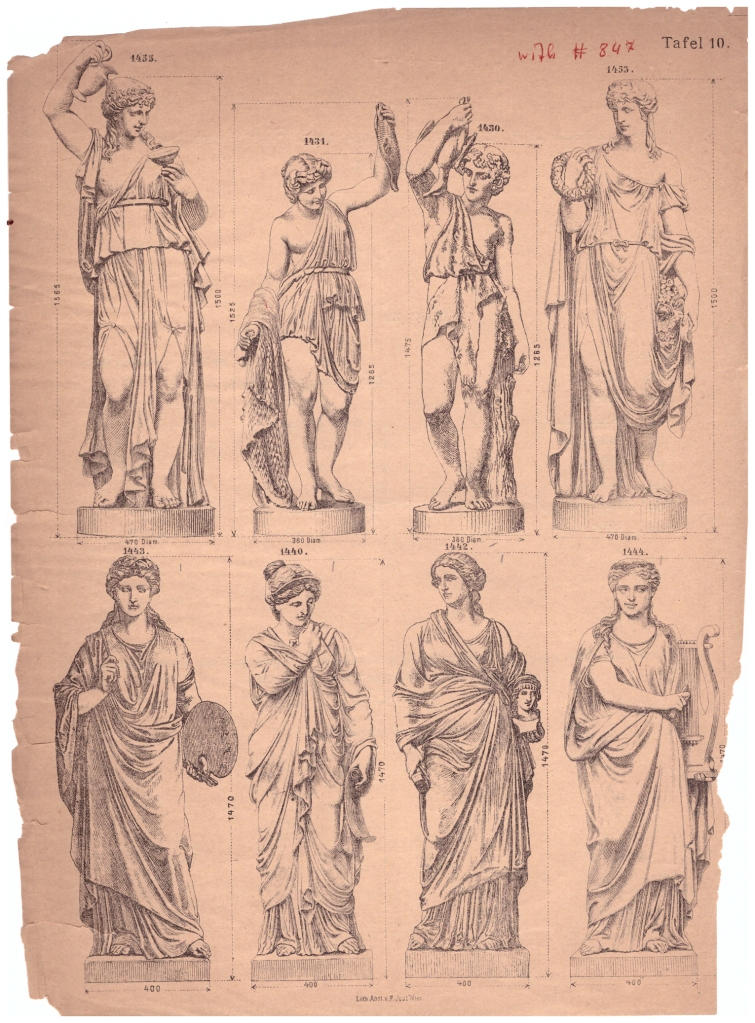

The twenty-three copies of famous Greek and Roman statues that once adorned the Iliou Melathron are now dispersed (according to Korres several of them are stored in the National Archaeological Museum). In the Heinrich Schliemann Papers at the ASCSA, there is correspondence between architect Ziller and the Viennese firm, Wienerberger Ziegefabriks- und Baugesellschaft, that made them, including a plate from their catalog.

Dr. Schliemann at Home

Schliemann and the Iliou Melathron would be the subject of a long article in The New York Times of April 22, 1882, titled “Dr. Schliemann at Home. His Palatial House and the Manner of his Life in It” (Bradley 1882). The author of the essay was a young American from Harvard, Charles Wesley Bradley (1857-1884), who had participated the previous summer in the excavations of the Archaeological Institute of America at Assos in northwestern Turkey, near Troy. Bradley described in his journal, now at the Archives of the American School, how he met Schliemann at Assos when the latter came to see their excavation. (About Bradley and Schliemann, read “All Americans Must Be Trojans at Heart”: A Volunteer at Assos in 1881 Meets Heinrich Schliemann.) Schliemann must have extended an invitation to Bradley to visit him at home when he came to Athens. As with Horton, who included an evening at the Iliou Melathron as a “must” in the social life of an upper-class traveler in Athens, Bradley also underlined the importance of paying a visit to Schliemann’s house:

“The interest of most modern travelers who visit Athens is probably about equally divided between the Parthenon and Dr. Schliemann. Of these two attractions the latter is much the less accessible; for the discoverer of Troy is so overrun by visitors, that Bellerephontes, the porter, is instructed to say “not at home” to all who approach the gate.” Schliemann, however, was not inhospitable; “his elegant house was opened every other Thursday during the winter” by leaving a calling card at the house.

Bradley recounted a conversation Schliemann had had with Ernst Ziller (1837-1923), the architect of the Iliou Melathron: I have lived in a little house all my life. Now I want to spend the rest of my life in a large one. I want plenty of room. Make it in any style you choose. I will limit you only on two particulars. I must have a broad marble stairway leading up from the ground and a terrace on the top.” Of course, it is hard to imagine what Schliemann meant by small but we know what he meant by large. Surely his house in St. Petersburg or that on St. Michael Street in Paris must not have been small. The Pooles described elaborate premises on the occasion of the couple’s first ball in Paris at 6, Place St. Michel. Bradley’s impression of the reception rooms on the first floor of the Melathron was that “300 or 400 guests might move with ease.”

After an elaborate description of the public rooms of the house, including Schliemann’s study room, and an informal encounter with Madame Schliemann and their young children, Bradley went on to describe a formal evening at the Iliou Melathron:

The Doctor stands by the entrance receiving his guests, who pass from him to Mme Schliemann, at the door of the salon. Here are distinguished men of all nations and professions, Greek statesmen, professors of the University, Athenian journalists, archaeologists of the French and German school, as well as a few from England, America [the American School of Classical Studies did not begin to operate in Greece until 1882], and Russia, and members of the different legations. The majority of the ladies are of course Greek, though a number of English, Germans, and Americans are present. You will hear a variety of languages, but none in which Schliemann and his accomplished wife cannot converse fluently.

From Bradley’s comments, we understand that an invitation to spend an afternoon or evening with the Schliemann household was highly sought and treasured, especially by the foreign members of the Athenian society because of the social opportunities these invitations offered. Nevertheless, as Bradley admitted, their popularity also lay “in the curiosity to see the man who, through his energy or his extreme good fortune or both, has made some of the most remarkable archaeological discoveries that the world has known.”

A year later, in 1883, Bradley’s essay in The New York Times was translated into Greek and published in ESTIA (ΕΣΤΙΑ), a popular family magazine.

Family Moments

The Iliou Melathron was a great showplace for Schliemann and one that fulfilled his wish to entertain large numbers of guests. But was it also agreeable for his family? Schliemann was famous for his long absences from home, sometimes away for more than half of the year. The fact that there is not a single-family photo in the Schliemann archive is telling. Instead, we find images of Schliemann by himself or Sophia with her children.

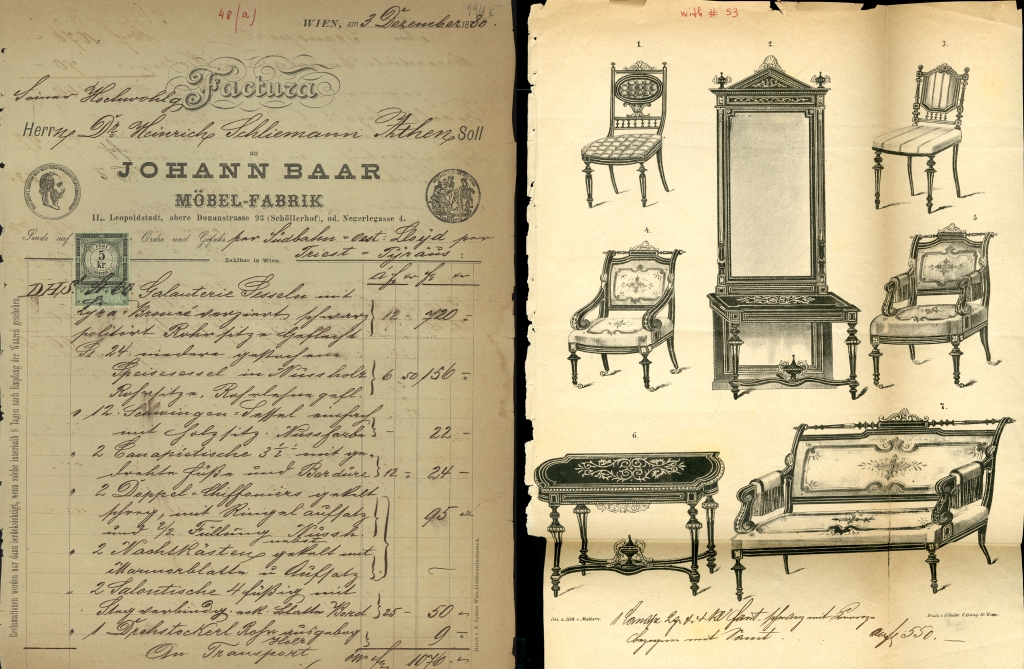

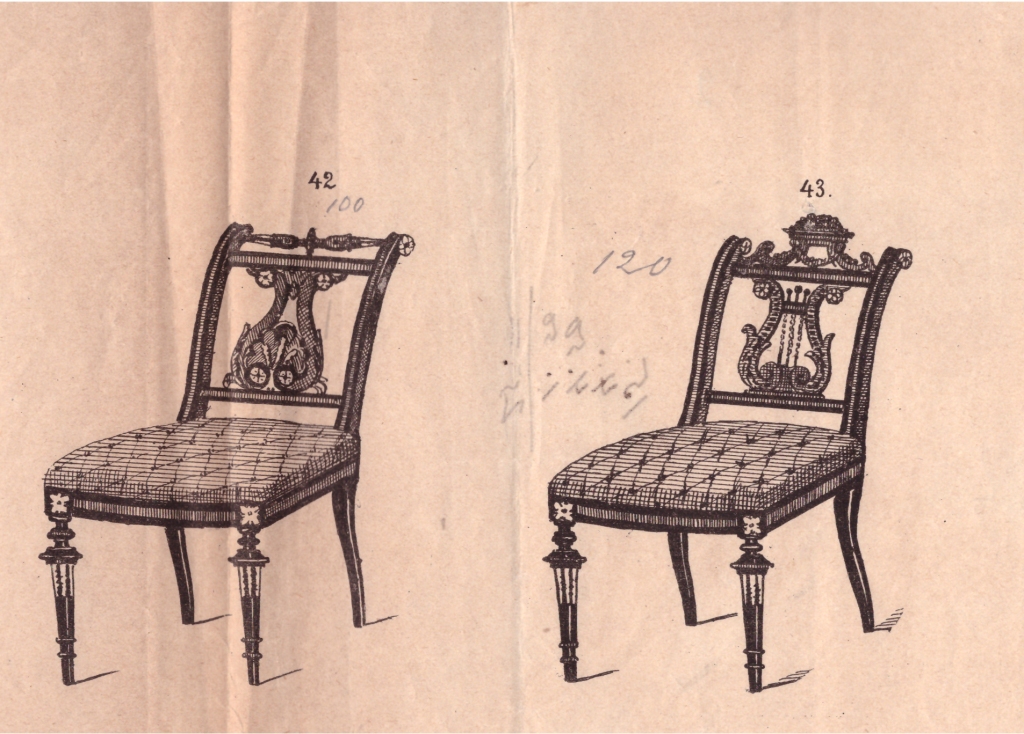

According to the Pooles, who based much of their book on Alex Melas’s memories of the place and through him those of his mother, Andromache, the Iliou Melathron was not a comfortable house to live in: “Heinrich had no use of curtains or draperies, for upholstered pieces that might be comfortable to relax in.” Nevertheless, in Schliemann’s papers there is extensive correspondence with a Viennese cabinet maker in 1880, Johann Baar (“Möbel Fabrik”), as well as pages that illustrate comfortable chairs and couches from the firm’s catalogue.

On November 18, 1880, an excited Sophia wrote to Heinrich that the furniture had just arrived and that “the chairs in the form of a harp were masterpieces.” In 1950 a doctor from Larissa, George Katsigras, bought Schliemann’s desk as well as some other furniture from his office, and these are now on display in the Municipal Art Gallery of Larissa. The rest of the furniture was probably dispersed among the children of Andromache Schliemann-Melas, after the house was sold in 1926.

It is said in the Poole book that, when Schliemann was away, Sophia would organize picnics for her children on the floors of various rooms and from there they would set out for imaginary destinations. “The Acropolis was the second-floor gallery; the Queen’s Garden was a back bedroom with windows overlooking the rear garden.”

Although furnished with a lush garden of trees and plants, the residents of the Iliou Melathron were not allowed to bring cut flowers into the house. One day when young Andromache tried to cut a flower, she was told by her father that the flowers experienced the same pain that humans felt when one of their fingers was cut off. While there was a profusion of flowers inside the house, “the blooms burst from the stems or the branches of flower bushes set in pots.”

Schliemann, however, was fond of animals and allowed his children to have pets at home. The cat, named Djindjinata, was rescued by Schliemann at Troy and after bringing her with him to Athens, it became Andromache’s pet. Soon after, the Schliemanns agreed to adopt a stray puppy that their little son Agamemnon (“Memeko”) had found outside their house: “Nero” lived there for many years, and was buried in the gardens of the Iliou Melathron.

At Madame Schliemann’s

In December of 1890, Sophia was anxiously awaiting Heinrich’s return from yet another long absence. She had also received a letter from him reminding her to send the invitations for their annual New Year’s ball. Alas, it did not happen because Schliemann died rather unexpectedly in Naples, en route to Greece, on December 26, 1890. Sophia was barely thirty-eight years at the time of his death, Andromache, nineteen, and Agamemnon, twelve. Two years later in October 1892, Andromache married the scion of a prominent Greek family, the lawyer Leon Melas (1872-1905).

Their wedding must have signaled the reopening of the Iliou Melathron, after a long period of mourning. Over the next three decades, Sophia, in the company of her daughter and son, would entertain frequently. Students and members of the American School of Classical Studies yearned for an invitation to spend an afternoon at Madame Schliemann’s or to be a guest at one of her grand balls. On April 15th, 1896, the year of the first Olympics, there were two events that Nellie M. Reed, a student of the American School, was to attend. (About Nellie Reed, see also “On the Trail of the ‘German Model’: ASCSA and DAI, 1881-1918.”)The first was a large reception for the American athletes given by the Annual Professor at the American School, Benjamin Ide Wheeler, and his wife Amey Webb, at the Merlin House near the Royal Gardens. A little after 11pm, Nellie and her friends walked from the Merlin House to the Iliou Melathron.

It was a very large and brilliant company, lovely gowns, beautiful jewels, and handsome uniforms. I might have had a stupid time if I hadn’t known all the Americans there but as it was I enjoyed it. I was with Mr. Andrews [another student of the American School] a good deal and he showed me the Library and several of the lovely rooms in the house. It is called the “House of Troy” and is most interesting – Mycenaean decorations, archaic motifs in mosaics and wall paintings… It is one of the things to be seen in Athens and I was glad to have had the opportunity” wrote an impressed Nellie to her mother. A week later she was back to Madame Schliemann’s for an early evening “and though the room was crowded I had the rare good fortune to have a charming talk with her [Sophia Schliemann]. It shamed me to hear her conversing with almost equal ease in four or five languages, turning from one to another (April 23, 1896).

In 1902, Sophia’s son Agamemnon was the center of a major scandal in three cities, Athens, Paris, and New York, having eloped to New York with a 16-year-old French girl, Nadine de Bornemann. The New York Times of June 22, 1902, described the event with much detail, under the head title: Eloped from France, Made to Marry Here. Son of Ancient Troy’s Excavator Got His Parisienne. Agamemnon Schliemann and Nadine de Bornemann Induced to Undergo a Civil Ceremony by Family Lawyers. Upon their return to Athens, the new couple moved in with Sophia at the Iliou Melathron. Sophia, with Nadine by her side, continued to participate in the social life of Athens, but with less vigor, after the sudden death of her son-in-law, Andromache’s husband, in 1905. Andromache, a young widow like her mother, needed Sophia’s help to raise her three underage boys. In the Melas Photographic Collection, there are several shots of the young Melas boys, one of which was Alex Melas, either in the garden or on the street outside the Iliou Melathron.

ASCSA Archives, Melas Family Photographic Collection

ASCSA Archives, Melas Family Photographic Collection.

Zillah Dinsmoor, a young American bride in Athens in the early 1910s, married to architect William Bell Dinsmoor (who would later become a famous architectural historian), was secretly hoping to receive an invitation to one of Madame Schliemann’s teas, and when she did she happily wrote to her mother: “I am going to Madame Schliemann’s next week, Thursday… I was so surprised to receive her card with ‘at home’ on it. She receives very little and I was frightfully excited last night when I found the card. She is the widow of Dr. Schliemann who did the first excavating in Greece. She herself found the lovely cow’s head of silver with gold horns at Mycenae. She has piles of money and lives in a magnificent big house a few streets above here” (January 10, 1912).

An early evening invitation to Madame Schliemann’s (5-9 pm) offered much more than a simple gathering:

The dancing was in a large room on the front of the house with a mosaic floor which was rather hard to dance on. Miss Negreponte introduced two men to me, otherwise I would not have danced at all. It is proper to take two or three turns about the room with one partner in the country… There were several French officers present in uniform with pretty red trousers and one Zouave with red trousers baggy to the ankles… Madame Schliemann stood in the hall by the door receiving… She is charming, very simple and quiet. I really do not remember what she wore but I think she was dressed in gray. She is the sort of person whose face and personality impress you much more that her clothes (January 23, 1912).

Zillah was equally impressed by Nadine Schliemann, Sophia’s daughter-in-law. “[She] is the most beautiful woman I have ever seen. She is tall with a magnificent figure and the head of a Greek goddess… She has fair hair which was knotted low on the back of her head… and wore a deep reddish-pink gown almost violet.” (About Zillah Pearce Dinsmoor, see also “Letters from a New Home: Early 20th Century Athens Through the Eyes of Zillah Dinsmoor” and “Expat Feasts in Athens on the Eve of the Balkan Wars.”)

In 1917, another member of the American School, Carl W. Blegen, was invited to have tea at Madame Schliemann’s, where Andromache shared with him her fine collection of embroideries. Fifteen years later, in May 1932, Blegen, by then an established archaeologist, would visit the elderly Sophia one last time, not at the Iliou Melathron, which had been sold, but at her new house in Phaleron. Blegen was on his way to Troy to re-open Schliemann’s excavations. Sophia did not live to see the new discoveries. She died a few months later (October 27, 1932), her death marking the end of an era.

Author’s Note

This essay first appeared in German, under the title “Zu Gast bei Schliemanns: Das Iliou Melathron als gesellschaftlicher Fixpunkt,” in Heinrich Schliemann und die Archäologie, ed. by Leoni Hellmayr, Darmstadt 2021, pp. 102-112.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Archives (ASCSA): Heinrich Schliemann Papers, Nellie M. Reed Papers, Zillah Dinsmoor Papers, Carl W. Blegen Papers and Bert H. Hill Papers.

Secondary Sources

C. W. BRADLEY, Dr. Schliemann at Home. His Palatial House and the Manner of his Life in It, The New York Times, 22 April 1882.

G. HORTON, Modern Athens (1902).

G. S. KORRES, Το «Ιλίου Μέλαθρον» ως έκφρασις της προσωπικότητας και του έργου του Ερρίκου Σλήμαν, in Αναδρομαί εις τον Νεοκλασσικισμόν (1977).

U. PAPPALARDO, Das «ILÍOU MÉLATHRON». Heinrich Schliemanns Haus in Athen, Antike Welt (2021) 55-63.

L. & G. POOLE, One Passion, Two Loves: The Schliemanns of Troy (1967).

A. PORTELANOS, Ιλίου Μέλαθρον. Η Οικία του Ερρίκου Σλήμαν, ένα έργο του Ερνέστου Τσίλλερ, in Archaeology and Heinrich Schliemann: A Century After his Death. Assessments and Prospects. Myth, History, Science (2012) 449-465.

R.M. RAKOFF, Ideology in Everyday Life. The Meaning of the House, Politics and Society 7:1 (1977), 85-104.

Dear Natalia,Great as always. Thanks. IÂ must have missed, somehow, the piece you wrote about Zillah Dinsmoor. Is there a way I can see it?Thanks, and a happy new year!TessaSent from Mail for Windows From: From the Archivist’s NotebookSent: Thursday, January 6, 2022 2:05 AMTo: tdinsmoor2@gmail.comSubject: [New post] At Home with the Schliemanns: The âIliou Melathronâ as a Social Landmark Natalia Vogeikoff-Brogan posted: " Heinrich Schliemann, the famous excavator of Troy, Mycenae, and other Homeric sites, was born in Germany on January 6, 1822–the Epiphany for western Europe and Christmas Day for other countries such as Imperial Russia and Greece which still used the Old"

Dear Tessa: Thanks for your note. You can read both essays about Zillah by clicking on the links. Natalia

[…] https://nataliavogeikoff.com/2022/01/06/at-home-with-the-schliemanns-the-iliou-melathron-as-a-social… https://www.dw.com/en/the-archaeologist-who-discovered-troy-heinrich-schliemann/a-60323937 […]

Nathalie, many thanks for such a fascinating account of the Schliemann’s household. You just wish you could step back there for an evening to see it all !

Thank you! Just as you said, we wish there was a time machine to travel us back in time.

(Apologies for spelling your name incorrectly! I should know better!)

[…] Schliemann was also an important authority in Athens, as was his wife Sophia, to whom Wiegand was introduced. (DAI, AdZ, NL Wiegand, Kasten 15, Diary entry 11.12.1888). In the colder months, Wiegand and […]

[…] was also an important authority in Athens, as was his wife Sophia, to whom Wiegand was introduced. (DAI, AdZ, NL Wiegand, Kasten 15, Diary entry 11.12.1888). In the colder months, Wiegand and […]