THE LIFE AND TIMES OF A DILETTANTE: RALPH HENRY BREWSTER

Posted: January 6, 2021 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, History of Archaeology, Mediterranean Studies | Tags: Georg Karo, Ralph Henry Brewster, Richard Stillwell 18 CommentsThe recent discovery of a head of Hermes in central Athens brought to mind another herm (one of the best of its kind), which was stolen from Greece almost ninety years ago. (A herm is a stone pillar with a sculpted head and genitals. In ancient Greece, herms were thought to have an apotropaic function and were placed at crossings, borders, and in front of houses or public buildings.)

I pick up the story in September 1932, when Richard Stillwell (1899-1982) returned to Athens after two months of vacation in America. A Princeton graduate and an architect by training, Stillwell had been appointed the new Director of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (1932-1935). He was no stranger to Greece or the American School (ASCSA or the School hereafter). As Fellow in Architecture in 1924, he had learned “the skills and rigors of archaeological fieldwork in the excavations at Corinth”; and as Professor of Architecture (1928-1931) he would begin a “long series of architectural studies which would form one of his major contributions to the field” (Shear 1983). In 1931-1932 Stillwell was Assistant Director during Rhys Carpenter’s last year in charge of the School. Starting with Stillwell the School introduced a new model of administration: new directors would learn the ropes by serving as assistant directors during the previous year. (This model was abandoned in the late 1960s, when it became increasingly difficult for incoming directors to extend leaves of absence from universities.)

Less than a month into his new position, Stillwell was confronted with a serious problem that had real potential to tarnish the School’s reputation in Greece. One of its students, Ralph Brewster, had committed a serious crime, involving the theft of a herm from the island of Siphnos, which he then smuggled out of the country. Although the crime had occupied the front pages of several Greek newspapers, it was only brought to Stillwell’s attention by Georg Karo (1872-1963), the Director of the German Archaeological Institute. Stillwell related the news to his predecessor, Rhys Carpenter, on October 2, 1932: “Karo called this afternoon, and as he was leaving told the following tale. Apparently, Brewster turned up at Siphnos last summer and tried to negotiate the purchase of one of the archaic Herms in the museum there. The scholarch, in charge, naturally refused, and later the herm was actually stolen, under what circumstances I do not know. The Greek authorities suspect Brewster of having had a hand in the matter.”

Why was Karo the one conveying the bad news to Stillwell? Brewster was an unusual student. Born in Florence in 1904 to an American father (Christopher Henry Brewster) and a German mother (Elisabeth von Hildebrand), he spoke fluent English, German, French and Italian, and traveled with ease in Europe. The Brewsters owned a former medieval convent in Florence dedicated to San Francesco di Paola (which remains in the family’s possession today). “It was here that his grandfather, the sculptor Adolf von Hildebrand, lived and worked and created a center of European culture where such visitors as Richard and Cosima Wagner, Clara Schumann, Ethel Smythe, Henry James, William Ewart Gladstone, and Bernard Berenson came and went,” as Harry Brewster (1909-1999), Ralph’s younger brother, recounted many years later in Out of Florence. Karo, also a Florentine, knew the Brewster family well and it is quite possible that young Ralph applied to the American School with his encouragement.

Why was Karo the one conveying the bad news to Stillwell? Brewster was an unusual student. Born in Florence in 1904 to an American father (Christopher Henry Brewster) and a German mother (Elisabeth von Hildebrand), he spoke fluent English, German, French and Italian, and traveled with ease in Europe. The Brewsters owned a former medieval convent in Florence dedicated to San Francesco di Paola (which remains in the family’s possession today). “It was here that his grandfather, the sculptor Adolf von Hildebrand, lived and worked and created a center of European culture where such visitors as Richard and Cosima Wagner, Clara Schumann, Ethel Smythe, Henry James, William Ewart Gladstone, and Bernard Berenson came and went,” as Harry Brewster (1909-1999), Ralph’s younger brother, recounted many years later in Out of Florence. Karo, also a Florentine, knew the Brewster family well and it is quite possible that young Ralph applied to the American School with his encouragement.

Unlike other student applications for the academic year 1931-1932, which were submitted by October 1931, Ralph did not apply until March 2, 1932. In his application, he listed the schools where he had studied: King’s College, London (Oct. 1925 – Jan. 1926; Oct. 1928 – June 1929), the University of Berlin (1929-1931), and the University of Göttingen (1931-1932). It is unclear if he graduated from any of these schools; however, when he filled out his application, Brewster stated that he was planning “to attain a Ph.D. in Archaeology from the University of Göttingen in December 1932.” He had joined the American School to acquire “practical experience in excavations and especially information for my dissertation.” Under the heading “languages” he noted that he spoke, read, and wrote German, French, and Italian “like a native.” In addition, his application says that he spoke Modern Greek fluently, which for a foreign student was as rare then as it is today (ASCSA Archives, AdmRec 108/1, folder 14).

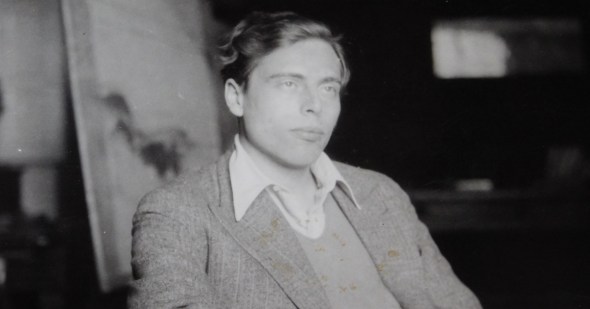

Ralph Henry Brewster, ca. 1930s. Source: Index-Culture_Gay and Gay Boys in Budapest.

Brewster appears to have been a rolling stone who invested very little time as a student of the School. Soon after his application, he became ill and “spent some time in the German School where they looked after him He then disappeared but was known to have been keeping company with some very shady Greeks… Nevertheless he slunk into the G[erman] School once or twice to get some things he had left there. Karo is very anxious, on account of his personal liking for the boy, and his long acquaintance with the boy’s family to get in touch with him, and if he is innocent of the theft, or of complicity in it to have him cleared” (ASCSA Archives, AdmRec 1001/1, folder 4, Stillwell relating his meeting with Karo to Carpenter, October 2, 1932).

Karo had already alerted museums in Germany to be on the lookout for a herm, and, if it showed up, to return the stolen property to Greece. He encouraged Stillwell to do the same, in case the stele appeared in America, which prompted Stillwell’s letter to Carpenter. In the meantime, Oscar Broneer, Professor of Archaeology at the ASCSA, had already informed Konstantinos Kourouniotis, the Director of the Archaeological Service, that Brewster had not been a real member of the School. Brewster did not live on the School’s premises and had only been engaged in the Corinth excavations for a few days.

A few months later, Carpenter replied to Stillwell that he was “πολύ ευχαριστημένος [very pleased] to hear that Brewster’s herm was seized, and not Brewster,” concluding that this was also the end of Brewster’s archaeological career in Greece. Indeed, we know from another source that Brewster was denied entrance to Greece for several years. Karo had managed to save Brewster’s skin by coming to “an understanding with the Greek authorities that they would wipe the matter out if the herm could be located and returned” (ASCSA Archives, AdmRec 1001/1, folder 4, Stillwell to Carpenter, October 2, 1932).

A Youthful Misdemeanor?

The Siphnos herm. Source: Leka 2000.

The herm that was stolen by Brewster now belongs to the collection of the National Archaeological Museum of Greece. It was listed among the new acquisitions of the Museum for the years 1930-1932: “ανήκει εις τη συλλογήν Σίφνου, οπόθεν κλαπείσα, απεδόθη ημίν εξ Ιταλίας (it belongs to the Siphnos collection from which it was stolen, and was returned to us from Italy)” (ArchEph 1939-1941, p. 12, no. 43). According to archaeologist Euridice Lekka, who in 2000 published an article about this small herm (NAM 3728), “it is the most famous sculpture from the island of Siphnos and the best-preserved hermaic stele of the Archaic period” (end of 6th century B.C.). It was found in the Castle (Κάστρο) of the island at the end of the 19th century by Alfred Schiff (1863-1939) and Ernst Curtius (1814-1896), but was considered lost for years. Its first publication in 1931, by the young German archaeologist Reinhard Lullies (1907-1985), was based on notes, drawings, and photos taken by Schiff and Curtius. In hindsight, I wonder whether Brewster and Lullies had known each other from Berlin. Brewster might have read a copy of Lullies’s dissertation on the typology of herms [Die Typen der griechischen Herme, Kόnigsberg, Prussia 1931], which remarked that the beautiful Siphnos stele was missing. Although Karo presented the theft of the stele as a youthful misdemeanor, under the bad influence of “some shady Greeks,” I am less inclined to believe that it was an act triggered by youthful enthusiasm and carelessness.

In a post-mortem publication of Lawrence Durrell’s notes, titled Lawrence Durrell’s Endpapers and Inklings 1933-1988, the famous English writer, who knew Brewster, recounted the Siphnos theft as follows:

“When he [Brewster] was a student in Austria, he went down and spent a summer in the islands –he spoke good Greek- in a caïque. And in Siphnos one afternoon they [who else?] found the museum wide open and the guardian asleep under a tree. He just said, ‘Go on, have a look around.’ So Ralph looked around and there was a beautiful little statue of a Pan lying on its back among the nettles of the garden, completely untended. And Ralph, who suffered from cupidity like us all, picked it up and put it in a shopping basket and carried it back to the caïque and took off with it to Austria. Well, nothing was heard of this loss for a little while, but the curator must‘ve noticed it was missing and unluckily for Ralph, they suddenly discovered it was one of the most celebrated examples of its period… They traced it to this youthful criminal… He probably risked a prison sentence, and he had to return the thing. Well, he returned it and was blackmarked and couldn’t go to Greece for five years after that. But when the sixth year came he managed to get a visa and he went back and in passing Siphnos again, out of curiosity, he called in to have a look at the museum and said ‘Oh well, they must’ve taken it to Athens’. Then he went outside in the garden and there it was in the same place, lying in the bushes when he’d found it first. On its back.”

Comparing Karo’s and Brewster’s (via Durrell’s pen) accounts of the theft, one realizes that Brewster’s version is fabricated and highly embellished, especially its last part. Brewster could not have seen the stele again on Siphnos upon his return to Greece (if he ever returned), because the stele remained in Athens at the Archaeological Museum after its repatriation from Italy. With his version of the story Brewster tried to exonerate himself: the Greeks did not really care about the herm, which would have been better appreciated in a European museum.

6,000 Beards

Today Brewster is better known as the author of a provocative book about Mount Athos. That same summer that he traveled to the Cyclades, he also organized a trip to the Holy Mountain together with a Greek friend of his, Iorgos (Brewster’s spelling). Apparently, he made the decision to visit Mount Athos after he heard an Italian archaeologist, “Dr. L.” say: “But of course there are women on Mount Athos! How would it be possible for six thousand men to live together without a single woman? I visited the monastery of Lavra last year, and I am sure that the under-secretary, at any rate, is a woman disguised as a monk. I made a photograph of him: there can hardly be any doubt, ‘You have only to look at his face –her face’.” Brewster does not name the Italian archaeologist except for his initial, but there is little doubt that he was referring to Doro Levi (1898-1991).

The 1935 edition.

Brewster published his personal experiences on Mount Athos in 1935, in a book titled The 6,000 Beards of Athos. The book sold out within a short time, and was reissued in 1939. Sixty years later, in 1999, The 6,000 Beards was republished, with an introduction by the President of the “Venice in Peril” fund, Jonathan Keates. It is an odd book, a mixture of travelogue tinted with sensational revelations. Historian and retired diplomat, Sir Michael Llewellyn-Smith, has called it a “curiosity, which strangely is in print.”

“The book departs from the norm in that, largely through the experiences of Yiorgos [Iorgos], it touches on the question of homosexuality on the Holy Mountain. Brewster himself was homosexual. His book is mildly shocking if it is true, and shocking in another way if it not true,” Llewellyn-Smith concluded in his review. (For more about books concerning Mount Athos, see M. Llewellyn Smith, Mount Athos. Perceptions of the Holy Mountain.)

In addition to being a colorful and provocative writer, Brewster was also a good photographer. The photos he took while on Mount Athos are impressive, both his landscapes and portraits. While only a small number of them were featured in The 6,000 Beards, Brewster published a larger selection to accompany an article he wrote for The Geographical Magazine (February 1936), titled “Athos: the Holy Mountain.”

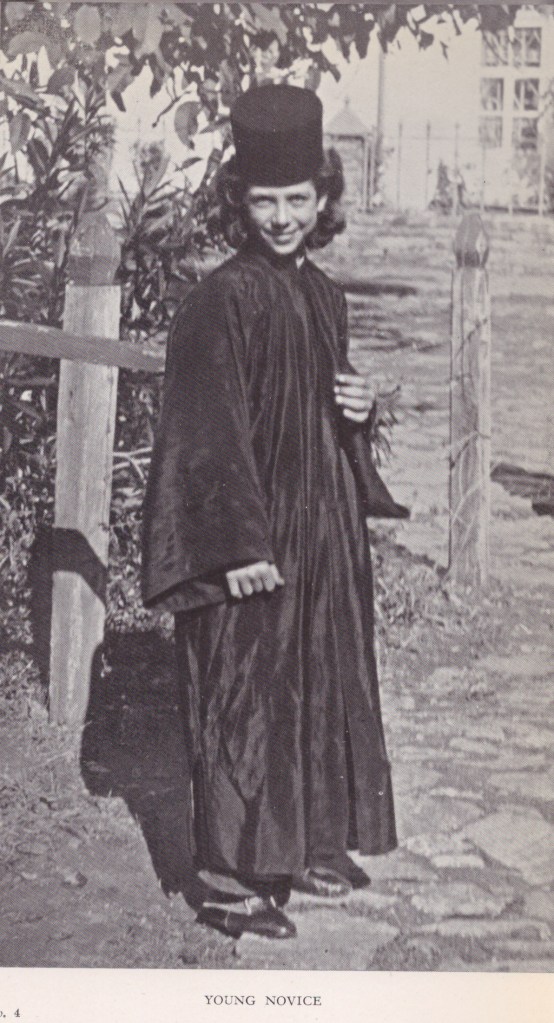

Monk and Iorgos. Source: The 6,000 Beards of Athos, London 1939.

One of the monks that “Dr. L.” probably thought “it was a woman disguised as a monk.” Source: The 6,000 Beards of Athos, London 1939.

Living at the Edge

Following the success of The 6,000 Beards, Brewster published another travel chronicle in 1939, The Island of Zeus: Wanderings in Crete, about his journey to the island (most likely in 1932). The book was reviewed by British classicist H.D. F. Kitto, who was rather unimpressed. “Mr. Brewster’s publishers tell us that his book on Athos ‘swept like wildfire through the sophisticated drawing-rooms of Mayfair’ –which is very good news. The Island of Zeus will be hardly so devastating” (The Classical Review 53:5/6, 1939, p. 226). Kitto goes on to praise the book’s photography and Brewster’s gift for retelling people’s stories, but finds boring and uninteresting the author’s various complaints about the weather and his lack of money. Another reviewer in The Geographical Journal (95:5, 1940, p. 388) was equally apathetic. Once again Brewster was praised for his photographs and certain parts of the narrative, but criticized for his “incessant confidences about his financial difficulties and his ignoble quarrels with the policemen.”

It is unclear where Brewster resided or what he did from the time of his expulsion from Greece until the beginning of WW II in 1939. At some point, he was in London mingling with the Bloomsbury Set. Virginia Woolf described him as having “curious teeth; gooseberry coloured staring eyes; and an air of nervous instability… A sudden amused kindling in the gooseberry eyes; and the profuse storytelling of those who have lived with savages […]. In the same entry he is described as “a musically talented exotic… who became involved with film world in Berlin, considered becoming a conductor… [and] edited a magazine called World Magazine in Vienna.” (There is a brief entry about Ralph Brewster in the Modernist Archives Publishing Project).

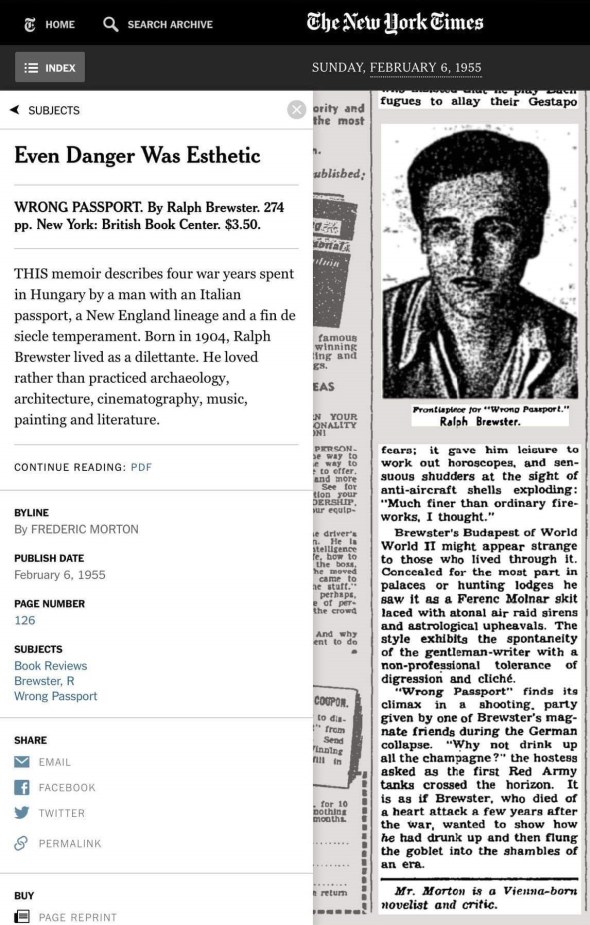

Brewster died of a heart attack in 1951 at the age of forty-five. His last book Wrong Passport, published posthumously (1955), is about his adventures during WW II, when he found himself hiding in Budapest after having repudiated his Italian citizenship. Once again he lived in a dangerous and flamboyant way “picking up odd contacts with Magyar noblemen and gypsies, astrologers and artists…” until he was eventually picked up as a deserter, but managed to return to Italy at the end of the War (Kirkus Review, February 1, 1955). (For his Budapest years, see also Katalin Eder, “Gay and Gays Boys in Budapest,” July 7, 2019.) The book also merited a review in The New York Times in 1955, titled “Even Danger Was Esthetic.” The reviewer, Frederick Morton, described Brewster as “an amateur in the most expansive sense of the word” and the book as “the product of an anachronistic temperament.” Brewster was a fin de siècle man and a dilettante with no particular focus. He certainly neither had a place at the American School nor in Greek archaeology.

Brewster died of a heart attack in 1951 at the age of forty-five. His last book Wrong Passport, published posthumously (1955), is about his adventures during WW II, when he found himself hiding in Budapest after having repudiated his Italian citizenship. Once again he lived in a dangerous and flamboyant way “picking up odd contacts with Magyar noblemen and gypsies, astrologers and artists…” until he was eventually picked up as a deserter, but managed to return to Italy at the end of the War (Kirkus Review, February 1, 1955). (For his Budapest years, see also Katalin Eder, “Gay and Gays Boys in Budapest,” July 7, 2019.) The book also merited a review in The New York Times in 1955, titled “Even Danger Was Esthetic.” The reviewer, Frederick Morton, described Brewster as “an amateur in the most expansive sense of the word” and the book as “the product of an anachronistic temperament.” Brewster was a fin de siècle man and a dilettante with no particular focus. He certainly neither had a place at the American School nor in Greek archaeology.

REFERENCES

Leka, E. 2000. “Ερμαϊκή στήλη από τη Σίφνο με αρχαία επέμβαση αποκατάστασης, Πρακτικά Α΄Διεθνούς Σιφναϊκού Συμποσίου,” Athens, pp. 325-342.

Pine, R. 2019 (ed.). Lawrence Durrell’s Endpapers and Inklings 1933-1988, Volume One: Autobiographies, Fictions, Spirit of Place, Cambridge.

Shear, T. L. 1983. “Necrology: Richard Stillwell (1899-1982),” AJA 87:3, pp. 423-425.

Thanks, Natalia. As usual, a fascinating account. In yesterday’s meeting of the Publications Committee, Camilla MacKay (Stillwell’s granddaughter) remarked that the new history of the School might be more interesting if it included more stories like this one!

Rob

>

Many thanks, Rob.

I agree with Rob. As I was reading this account, I thought part of it, whither a photo of the herm and Brewster would make a great sidebar. I also still think we should do a book of your posts!

Jane

Fascinating story, Natalia. It is always interesting to trace the travelers who cross paths with the American School, in this case happily, ever so briefly and tangentially. Is there any hard evidence that women were slipped into Mt Athos or is this just a case of a delicate-looking young monk? Happy New Year and stay safe. Thanks for the contribution.

By ignorance, I would say. In his introduction, Brewster included an incident that involved Aliki Diplarakou, Miss Greece and Miss Europe in 1930, who docked with her fiancee’s yacht on one of the shores of Mount Athos and wandered off for a while until she was caught.

Many thanks, Natalia, for this most illuminating report, especially for bringing to our attention Brewster’s book on Mt. Athos. An alternative and very enlightening account of a visit to Mt Athos in the ’30s is published in the last chapter of Patrick Leigh Fermor’s The Broken Road, which completes his famous trilogy on his walk on foot from Holland to Istanbul in 1935. Always your fan, Happy New Year, Nassos

Many thanks for your comment Nassos. I will look for it.

Natalia,

I tried posting this comment to the piece on Haspels but when I went to exit it would no accept my old pw (which it says was stolen in 2013 or something like that) or allow me to change it. It also did not like my my email used as username — and I know of no other for the site. So I gave up. Here it is in any case, since it looks like it was not saved and posted.

Thanks, Natalia (and Filiz Songu), for shining this fascinating light on one of the most important contributors to the study of Attic pottery. I have always wondered about the disconnect between her early magnum opus ABL and her post-war career, which this helps explain. It also explains something else that has always seemed remarkable: “It was written in English by a Dutch female archaeologist from Oxford who had become a foreign member of the French School at Athens, which published it (Dugas 1937, p. 40).” It is heartening to read how all those scholars helped her overcome the substantial barriers presented by nationalism, a tendency that fortunately continues to benefit us all in our deeply international field. Bob

The Brewster piece that initially puled me in for some reason was also interesting, but in a more disturbing way, but raises other impotent issues.

I hope you are all well and surviving this pandemic. The Greek Covid spike shown at today’s MC meeting was disheartening. Susan and I are ok, and the lockdown is not that much different from retirement in many ways. Hopefully we can meet face to face again before too long. Fortunately Peter has been able to visit from Detroit after testing negative and driving straight through; he’s been working at home, so this has been a big pleasure for us all. He’s still working for Ford. Thanks for all you help with recommendations.

Best to you all,

Bob

Robert F. Sutton, Ph. D.

Classical Archaeologist

Professor Emeritus

IUPUI – Indiana University

376 Merion Rd

Merion Station, Pa 19066 (USA)

rfsutton@iupui.edu

(01) 484.278.4379

(01) 317.626.6728 (mobile/text)

I am glad you figured out how to post comments. Thank you for reading my stories.

It does seem we need a Procopius to write “A Secret History of the ASCS”…there are so many stories that will be lost as the older generation who heard them from the oldest generation disappears. My PhD supervisor, Robert Scranton, told me about the proposal at Ancient Corinth in the 1930s, for example, to blow up the West Shops to get rid of them because it was thought they were Byzantine or Frankish…They were saved when it was realized they were Roman.

Thank you Hector. The inspiration for my writings comes from archived documents.

Thoroughly enjoyed this piece. Sounds like a fascinating character. Grateful to learn about Brewster’s book about Mt Athos. Thank you!

Thanks for insight into this character.

[…] THE LIFE AND TIMES OF A DILETTANTE: RALPH HENRY BREWSTER → […]

Dr. Hans-Ulrich Seifert from Trier has kindly shared the following information with me via e-mail, which I reproduce with his permission:

Great to read this fascinating account of the Siphnos herm theft. Blue Danube, a sister imprint to the 100 year old Blue Guides, last year re-issued Ralph Brewster’s Wrong Passport with extensive notes.

Thank you for your comment. I will look for the reissue.

[…] French, and Italian, and traveled with ease in Europe. I have written about Brewster before (THE LIFE AND TIMES OF A DILETTANTE: RALPH HENRY BREWSTER) when I discovered in the Archives of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA […]