Henry Miller’s Timeless Greece through the Drawings of Anne Poor

Posted: June 1, 2015 Filed under: American Studies, Archival Research, Mediterranean Studies, Modern Greek History, Modern Greek Literature, Philhellenism | Tags: Anne Poor, George Katsimbalis, George Seferis, Henry Miller, Lawrence Durrell, Michel Déon, The Colossus of Maroussi 4 CommentsIt is not a land which was discovered by some migratory tribe or race; it is an invention of the gods.

Henry Miller, Greece (1964)

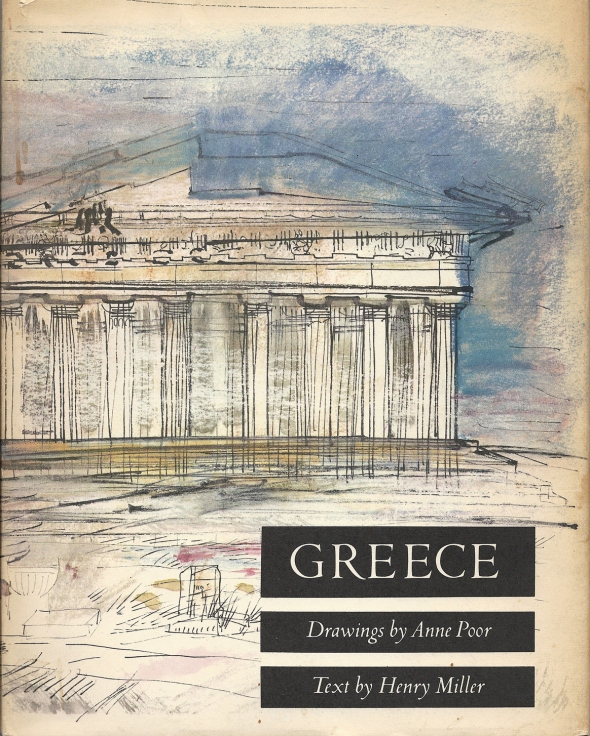

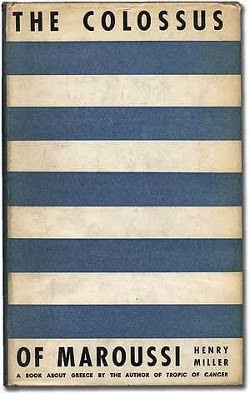

In the early 1960s Henry Miller was invited to contribute text to a picture book with drawings by Anne Poor: GREECE was published in 1964 by the Viking Press. It’s a small book, a little more than fifty pages long, with color drawings and pen sketches of ancient monuments, picturesque landscapes, scenes of daily life, and portraits of people. I became aware of this handsome publication when Deborah Ninios, who has been volunteering in the School’s Archives for several years, gave it to the Gennadius Library as a gift. The book immediately caught my attention because I was not previously aware that Henry Miller (1891-1980) had written anything else about Greece after The Cοlossus of Maroussi (1941; hereafter The Colossus; for my references below I use a 2007 edition from Summersdale Publishers). In fact, Miller started GREECE by stating:

“Since writing The Colossus of Maroussi, on my return from Greece in 1940, I have never written another line about Greece and probably would not now had I not happened upon these colored drawings by Anne Poor. A glance at these vivid impressions and I feel as if I were reliving my stay in Greece.”

Miller’s Colossus is a time-capsule. Not only did it capture a myth-making period in the life of a group of highly creative people, it also created “a new kind of Byronism,” a new geography, and a new cosmos for Greece (see David Roessel’s concluding chapter In Byron’s Shadow, Oxford 2002, p. 252). Ancient ruins and modern shepherds were not the protagonists of Miller’s Greek myth. Their place had been taken by a παρέα (group) of Greek male intellectuals (George Katsimbalis, who inspired the title of Miller’s book, George Seferis, Lawrence Durrell, and Nikos Hatzikyriakos Ghikas, just to mention a few). (For a wonderful analysis of Miller’s Colossus, also read Edmund (Mike) Keeley, Inventing Paradise [1999]).

Though Miller in letters to Seferis and Katsimbalis talked about coming back to Greece, he never returned. A few years ago I read the correspondence between George Katsimbalis and George Seferis, «Αγαπητέ μου Γιώργο»: Αλληλογραφία (1924-1970), ed. Dimitris Daskalopoulos (Athens 2008). The informal tone of their letters, as well as the book’s handy commentary, makes for delightful reading. In the book there are several references to Henry Miller post-1939. After a hiatus of some years because of WW II, Seferis and Katsimbalis resumed correspondence with Miller. While Miller wrote to Seferis during the war, Seferis could not then find the right mindset to communicate his country’s (and his personal) sufferings. In his personal journal (Μέρες Δ’), Seferis scribbled on October 21st, 1944: “Yesterday I finished reading the Lost Traveller. For the first time I have a desire to write to Henry Miller who has not forgotten me. I hope he forgives me for not having had the stamina to respond to his message, now for two years ” (my translation). I am not sure to which Lost Traveller Seferis refers, since the one by Antonia White was not published until 1950. Or is he referring to William Blake’s “lost traveller’s dream under the hill”?

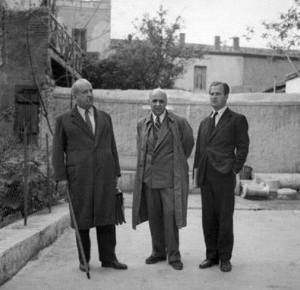

George Katsimbalis, George Seferis, Patrick Leigh Fermor, ca. 1950. Fermor published an inspiring portrait of Katsimbalis in The New Griffon (New Series) 3, 1998, pp. 10-14.

What he could not do in 1944, Seferis did a few years later. In a letter to Katsimbalis from Ankara (May 19, 1949), Seferis wrote:

“’The King of Asine’ made me resume my correspondence with Henry Miller. I wrote to him about Greece. ‘I look at your letter which made me weep,’ he wrote me; he sends me books. He is infatuated with [Blaire] Cendrars. Miller is a man full of vim and vigor, bigger than his talent” (my translation).

Katsimbalis conveyed more news about their mutual American friend in 1954, when he traveled to United States under the Smith-Mundt Act (an exchange program which allowed European literary figures to travel to America with all expenses paid as part of the U.S. government’s Cold War cultural diplomacy program). Katsimbalis visited Miller in Big Sur: “I stayed at his place for two days. It’s a dream place. I will be forever grateful to him for allowing me to see one of the best corners of the world. He looks old and down. His new wife, the Jew, is charming and very sweet. His children: wild, bloodthirsty creatures. Next spring he is planning to travel to Palestine, Cyprus, Beirut, and then to Greece to conclude his trip, where he is thinking of staying for a while… Let’s welcome him! I understood that loneliness has hit him hard and he feels the need for company and outside contact.” “Yet, will he find in Greece what he is looking for? I doubt it,” Katsimbalis wondered (my translation).

Seferis, on hearing that Miller was thinking about going to Cyprus, worried that he would receive a skewed view of the island’s political situation and its people from Larry Durrell, their other common acquaintance (and Miller’s closest friend from his Paris days). Durrell lived in Cyprus and worked for British intelligence in the 1950s. Durrell and Seferis held entirely opposite views concerning “the Cyprus issue,” with Seferis supporting the island’s unification with Greece and Durrell favoring the island’s dependence on the British crown (read Bitter Lemons by Durrell). “I am certain that Larry will pick him up and try to show him the island the way they [the British] think: namely, that the Cypriots are not Greeks but bastards who lack in fighting spirit, aliveness, etc. Only you could prevent Miller from falling into the trap…” wrote a worried Seferis to Katsimbalis on Nov. 13, 1954 (my translation).

Miller did not make it to Greece in the 1950s or ever again. The next time Seferis mentioned him to Katsimbalis was in 1958. Miller had sent Seferis a copy of his latest book (most likely Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch, which was published in 1957) but had also asked Seferis to help Alexandros Venetikos, the guard of Phaistos, to get a salary raise. Miller describes his meeting with Venetikos at length in The Colossus. After sharing lunch and communicating “in the deaf and dumb language of the heart,” Alexandros Venetikos begged Miller to stay a few more days at Phaistos because he was lonely. Nobody visited the site anymore, Venetikos lamented.

“He got out the guest book to show me when the last visitor had arrived. The last visitor was a drunken American apparently who had thought it a good joke to sign the Duke of Windsor’s name to the register, adding ‘Oolala, what a night!’ wrote Miller in The Colossus.

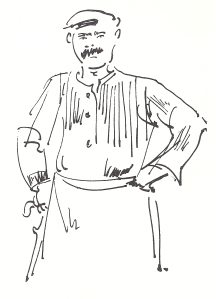

A sketch of the “custodian at Phaestos” by Anne Poor (Alexandros Venetikos?). Poor and Miller 1964, p. 17)

Phaistos mesmerized Miller. He found the site feminine. He writes: “Phaestos contains all the elements of the heart; it is feminine through and through. Everything that man has achieved would be lost were it not for this final stage of contrition which is here incarnated in the abode of the heavenly queens” (p. 166).

About twenty years later, a glance at Anne Poor’s color drawings (“these vivid impressions of hers”) would rekindle Miller’s old passion for Greece and inspire him to write an “epilogue” to his 1939 journey. For Miller, Poor’s drawings had captured everything that made Greece “a land of near and far, of heights and depths, of the familiar and the insolite”; but also the “almost perfect marriage of landscape and people (Poor and Miller 1964, pp. 8, 19). Without a classical education cluttering his mind and impeding his vision, Miller did not distinguish between ancient and modern Greece.

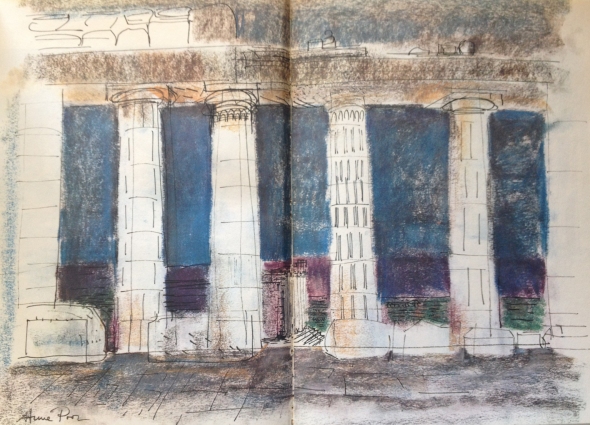

Of Poor’s three Parthenon sketches he was “most drawn to the one in which the blue –and what a blue!—sweeps through the marble columns like the play of sea and sky combined” (Poor and Miller 1964, p. 18).

Although GREECE was published in 1964, Anne Poor made her Grecian sketches shortly after WW II, when she spent two years abroad in Italy and Greece (S. Moore, “Anne Poor,” Woman’s Art Journal, 2:2, 1981-82, p. 51). Other evidence concerning the exact time of her presence in Greece comes from a small sketch in the book that is dated “26/4/50.” In addition, she thanks “Professor and Mrs. John L. Caskey” in her acknowledgements. When they met it must have been Jack Caskey’s first academic year as director (1949-1959) of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. Miller’s text, based on memories of his 1939 journey, and Poor’s drawings are thus separated only by a decade.

Anne Poor (1918-2002), who is known today primarily as a muralist, and Miller were old acquaintances from Paris. Anne spent 1937 in Paris as a student of painter Abraham Rattner, Miller’s life-long friend. Miller and Rattner traveled from New York to New Orleans in the winter of 1940-41, and a little later they published together Our America, describing that trip and illustrated with drawings from it. Anne Poor and Miller must have kept in touch after Paris, in order for them to have joined efforts to publish GREECE. Miller liked her work; he found her sketches as “evocative and penetrative as a huge canvas sometimes” (Poor and Miller 1964, p. 20).

In 1940 Anne Poor assisted her step-father, Henry Varnum Poor, with a mural commissioned by the Pennsylvania State University. (Source: Penn State University, CC BY-NC 2.0)

With most of her paintings in private collections today, it is not easy to relate her sketches to the monumental frescoes she also produced. In the 1940s Poor was commissioned to produce murals for post offices in Gleason, Tennessee, and Depew, New York. It is in her oil “Spring Morning on the River” (1976; reproduced in Moore’s essay, p. 52, fig. 2) that I find connections with her Grecian sketches, especially that of the island of Syros (Poor and Miller 1964, p. 36).

The last time Miller is mentioned in the Katsimbalis-Seferis correspondence is in June of 1961. Katsimbalis was upset because Michel Déon, the author of a new best-seller about Greece, Le balcon de Spetsai, had written an unflattering account of Katsimbalis’s encounters with Miller in 1939 and 1952. Based on what Katsimbalis had told him in a casual conversation, Déon wrote that Katsimbalis didn’t like Miller at first, that he avoided him because he was afraid that Miller would ask for money, and that he hated the fact that Miller was so inimical to his country. Of course, after Miller dedicated his Greek book to him, Katsimblis later felt guilty about having treated Miller so dismissively.

Although in his letter to Seferis Katsimbalis denied having ever said anything bad about Miller, I am tempted to believe that Déon did not make all of it up… . Déon, who is today still alive at 96, lived for many years on the island of Spetses in the 1960s, before making Ireland his permanent home. Author of many novels, he was awarded in 1973 the “Grand Prix du roman de l’ Académie française” for his novel Le taxi mauve.

Although in his letter to Seferis Katsimbalis denied having ever said anything bad about Miller, I am tempted to believe that Déon did not make all of it up… . Déon, who is today still alive at 96, lived for many years on the island of Spetses in the 1960s, before making Ireland his permanent home. Author of many novels, he was awarded in 1973 the “Grand Prix du roman de l’ Académie française” for his novel Le taxi mauve.

But I also suspect that Katsimbalis’s characterizations did not offend Miller. One thing he admired in Katsimbalis was his extemporaneity. “I’m an extemporaneous fellow. I like to hear myself talk. I talk too much – it’s a vice,” he told Miller back in 1939. “The best stories are those which you don’t want to preserve. If you have any arrière-pénsee the story is ruined… you must throw it to the dogs…” (p. 72). That was Katsimbalis’s philosophy, and “I have a little of it myself” the anti-conformist Miller admitted in The Colossus (p. 33).

I am not sure what kind of travel literature English-speaking visitors, especially younger ones, read nowadays in preparation for a trip to Greece. I suspect that The Colossus still remains a recognizable title and I am about to test this hypothesis.

Every year in early June, my colleagues and I give a tour of the ASCSA Archives to students in the two Summer Sessions of the American School. Participants are primarily American undergraduates but also include a few older high-school teachers. Part of my routine is to show students the manuscript of George Seferis’s poem King of Asine (written between 1938 and 1940). Sometimes, I refer to the great παρέα of intellectuals whom Miller met in the summer of 1939. How many heads will nod when they hear the title of Miller’s book? And then how many mouths will respond to the more important question: Who was Miller’s Colossus?

Great stuff, Natalia. Just out of curiosity, did Anne Poor meet Kevin Andrews when they were both in Athens at the same time in the late 1940s?

Thanks, Glenn. Let me do some checking since it is not certain that Anne Poor appears in the School’s records (since she did not come as a member) despite the fact that she thanks John Caskey for facilitating her staying in Greece. I will get back to you shortly.

Lovely drawings, Natalia. Thanks for posting this.

You may like to know that in fact Miller published another small book about Greece, First Impressions of Greece (Santa Barbara: Capra Press, 1973). He gave a notebook with his jottings about Greece to Seferis at the end of 1939, and they were published after it passed to Maro Seferiades in 1971. The book includes facsimiles of some of the notebook’s pages.

Thank you for this. I knew about the journal of 1939 that H.M. gave to Seferis upon his departure from Greece (Mike Keeley compares the journal with The Colossus in his Inventing Paradise) but I didn’t know that it was published. I will check it.