“You Undoubtedly Remember Mr. L. E. Feldmahn”: The Bulgarian Dolls of the Near East Foundation

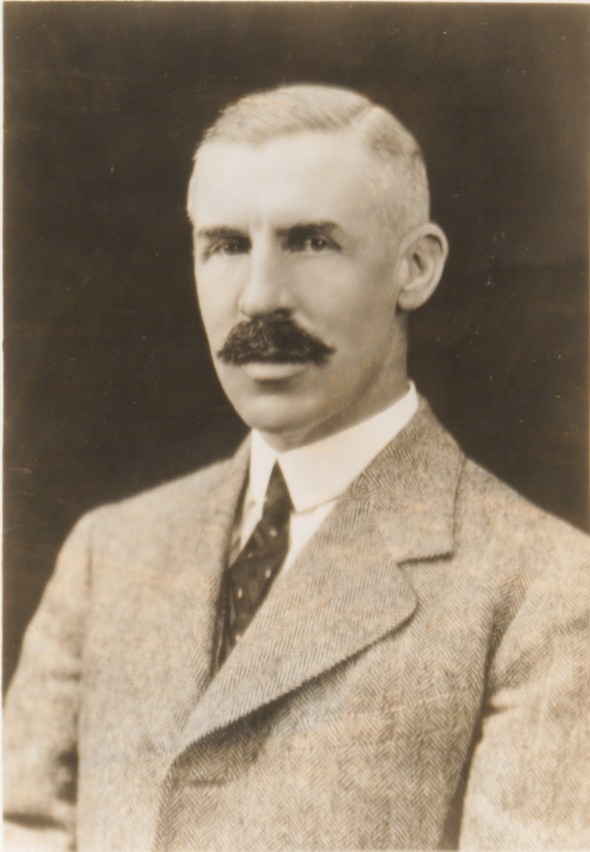

Posted: August 31, 2024 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Economic History, Greek Folk Art, Greek Folklore, History, History of Archaeology, Mediterranean Studies, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism, Uncategorized | Tags: Dolls, Leonty E. Feldmahn, Near East Foundation, Near East Industries, Near East Industries Sofia, Near East Relief Museum, Priscilla Capps Hill, Rockefeller Archives Center 2 CommentsJack L. Davis, Carl W. Blegen Professor of Greek Archaeology at the University of Cincinnati and a former director of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (2007-2012), here contributes an essay about Leonty E. Feldmahn, the man who conceived and produced in the 1930s the Bulgarian dolls of the Near East Foundation.

One rewarding sidelight of researching institutional history is that, from time to time, it affords an opportunity to resurrect once well-known individuals who have been lost to history. Here I call attention to a fascinating man, who, throughout much of his life, made outsize contributions to addressing one Balkan refugee crisis that resulted from the Russian Revolution of 1917. In the years prior to World War II, his activities in Bulgaria were sometimes tangential to those of certain individuals known to readers of this blog through the intermediary of the Near East Industries subsidiary of the Near East Foundation.

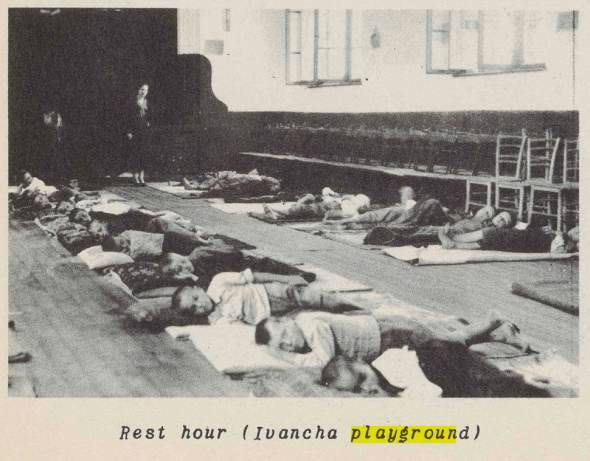

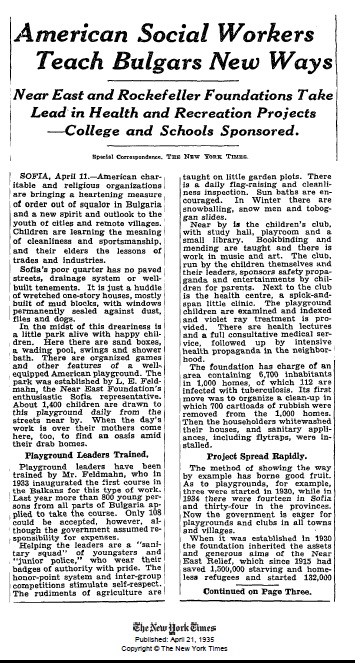

I only learned of Leonty E. Feldmahn recently and by accident. I didn’t remember him from any earlier reading. Feldmahn is not mentioned in the standard history of the Near East Foundation, or on the Foundation’s historical web site. He appears only three times in the New York Times: when he was awarded the Bulgarian Cross for Philanthropy from King Boris (he had in 1923 established “a playground and children’s club in Sofia serving 4200 poor children,” December 31, 1935, p. 17); earlier in 1935, when the character of the playground and club was described in detail (April 21, 1935, pp. 78, 80); and in his obituary (January 6, 1962, p. 16).

It was my passion for costume dolls made by refugees that brought Feldmahn to my attention. When I first began to collect dolls manufactured under the auspices of the Near East Foundation, I mistakenly thought that Athens was their sole center of production. Then a Minnesota-based seller on EBay told me she had Near East Foundation dolls made in Sofia. I soon found that another seller claimed his collection had two dozen Bulgarian dolls of different types. The Minnesota seller couldn’t find the Greek doll I had purchased in her auction (“misplaced in a closet”), and kindly offered me a cash refund or a replacement, either Bulgarian or Athenian. In photos she sent I noticed that one Bulgarian doll was mounted on a stand embossed with the name Kimport, Inc., a major distributor of dolls made by refugee women in Athens under the auspices of Near East Industries. I opted for a Greek doll then—but my curiosity was piqued.

My focus on collecting dolls produced in Athens by Near East Industries took precedent. But I never forgot the Sofia doll industry, and later purchased the several Bulgarian dolls recently displayed in the exhibit, In the Name of Humanity, staged in the Makriyannis Wing of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. I knew that I wanted to search the archives of the Near East Relief and the Near East Foundation in the Rockefeller Archives Center in Sleepy Hollow, New York, for more information about the Sofia dolls, but I had trouble finding the time.

Forward movement came only in the late fall of 2023 when Jennifer Sacher, editor of Hesperia, Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA), volunteered to go to Sleepy Hollow on my behalf. I owe this post to her. Jen sent me electronic copies of valuable records: Annual and Project Reports, Dockets, and Minutes of the Executive Committee, Finance Committee, Program Committee, Board of Trustees, and Board of Directors, as well as correspondence and other materials in files that had belonged to Rose Ewald, U.S. director of Near East Industries.

Bulgaria, after Greece, gradually became the largest European theater for humanitarian efforts of the Near East Foundation, and the brains behind several of its operations in Sofia was Feldmahn:

“You undoubtedly remember Mr. L. E. Feldmahn. He was once an officer in the White Army of Russia–later he became a Russian Red Cross official in Bulgaria. During recent years he has been in charge of our Near East Foundation playground and health center in Sofia. When the Near East Relief sent me to Bulgaria in the summer of 1926, I found Mr. Feldmahn in charge of a poverty-stricken orphanage for Russian refugee children, a hospital and an encampment of crippled Russian soldiers and refugees. I never saw a more pathetic or impoverished group; in spite of splendid administration and scrupulous economy, the men, women and children were undernourished, dressed in tatters and indescribably woebegone. I had to tell them that Near East Relief had already undertaken more obligations than it could carry and that we could give them very little money. But we did give them a large shipment of old clothes and an idea. We described the Good Will Industries of Boston to the resourceful and courageous Feldmahn. He set his Russian refugees and crippled soldiers to work patching and renovating, first for their own use and later for sale to other refugees at a price that would pay wages to those who re-soled the shoes and renovated the clothing. It was Feldmahn who developed the plan. He invented the idea of making beautiful dolls from scraps of old clothing and dozens of other ingenuous by-products. Out of the profits he succeeded in supporting hospitals, orphanages and soup kitchens for undernourished children.” (Near East Foundation Records, Report by Barclay Acheson, Director of Overseas Operations for the Near East Foundation, “Report of the Executive Secretary to the Board of Directors,” October 22, 1936, p. 7, Dockets of Board of Directors Meetings, FA1305_B3).

Before the Bolshevik Revolution Feldmahn served as assistant to the state secretary of the council of the Russian Empire, while his wife, Vera, had been a lady-in-waiting to the czarina. The couple fled from St. Petersburg to the Caucasus in 1917, and from there to Bulgaria in 1920, where they joined 25,000 other Russian refugees [3].

Dolls had been made in Sofia already for some time when officers of the Near East Foundation in Greece, and afterwards of its subsidiary Near East Industries, began to explore their potential marketability in America [4].

A letter from Harold B. Allen, Near East Foundation Director of Education in Salonica (formerly a professor of agriculture at Rutgers and author of Come Over Into Macedonia; see his obituary in the New York Times 11 July 1970, p. 20), to Feldmahn in early 1937 provides background for the circumstances that led to doll marketing in the U.S.:

“You should know that the costume dolls which I brought down from your shop made a big hit here in Salonica. The two additional dolls which you kindly brought down, as result of my cable, were for the wife of the American vice-consul [James H. Keeley, Jr., father of Mike Keeley, renowned translator and trustee of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens]. We have difficulty in holding [sc. onto] our own dolls as so many people have wanted them, but Mrs. Allen would not give them up. My experience here leads me to feel that there would be quite a market for these dolls if they were where more people could see them. I imagine that New York could sell a good many, but I expect it would be out of the question to ship dolls to New York and pay the necessary duty without resulting in a price which is altogether too high […]. One reason for the interest in your dolls is that so many people would like to buy native costumes and yet find them too expensive and so seem to be glad to turn to a doll as a means of showing what the native costumes are […]. New York will see a copy of this letter and may have some comments to make on this question on dolls.” (Near East Foundation Records, “Bulgaria Dolls 1935- 1941, Folder 1,” January 25, 1937, FA406, Box 33) [5].

Indeed, New York’s Ewald of Near East Industries did comment right away:

“Mr. Allen was good enough to send the copy of his letter to you under date of January 25th. During the time that he was here, he became aware of the very definite effort I am making to supply the increased demand of dolls for collection. Mr. [Edward C.] Miller has suggested in view of the comments in that letter that I write to you and see what could be done in Bulgaria to create an 8” doll showing definite types of costume which must be authentic and of which we must have the historical background. We need to know the price and the probable cost of delivery to America. After this, there will be the duty. It seems to me that since the commercial people are bringing in an excellent type from Russia, Czechoslovakia, Germany, and also some from China and Japan, that we ought to be able to produce acceptable ones from our territory. Aside from the possibility of the industry providing work for your people, they add greatly to the international interest and may be used effectively in our promotional work.” (Near East Foundation Records, Ewald to Feldmahn, February 16, 1937, “Bulgaria Dolls 1935-1941, Folder 1,” FA406, Box 33).

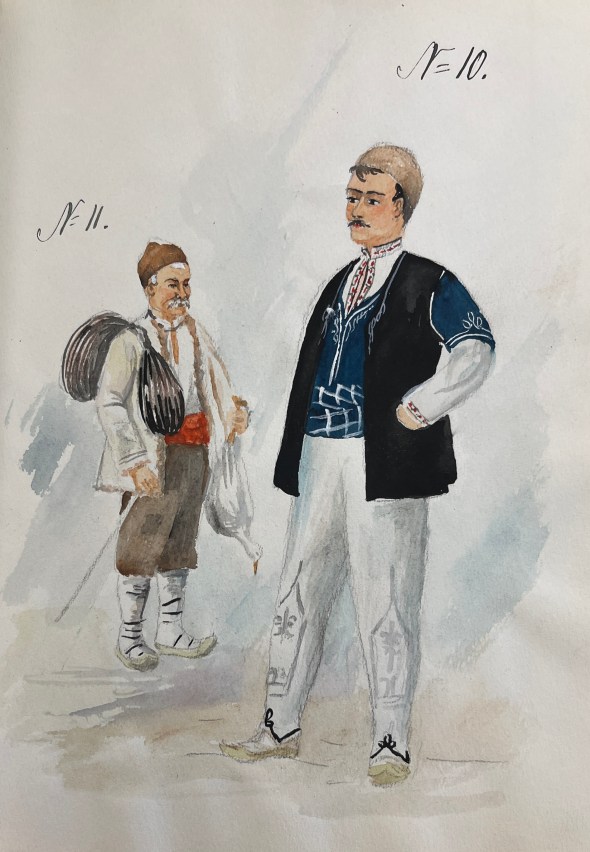

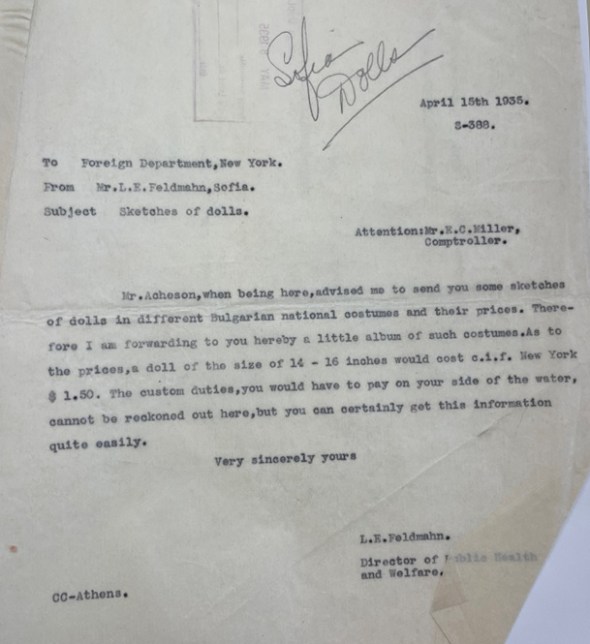

By March, Feldmahn had already assured Miller, comptroller of the Near East Foundation (A Lasting Impact: The Near East Foundation Celebrates a Century of Service, p. 43) , that he could produce an 8” doll at $1.00-$1.20 per unit. (March 18, 1937, “Bulgaria Dolls 1935-1941, Folder 1,” FA406, Box 33). This was not, however, the first time that the production of Bulgarian dolls for export to America had been discussed with the offices of the Near East Foundation in New York. Already on April 15, 1935, on the advice of Acheson, Feldmahn had sent a folio with sketches of costume types to Miller, estimating that he could produce a doll of 14-16 inches height for $1.50 c.i.f. [cost, insurance, and freight] New York (Near East Foundation Records, “Bulgaria Dolls 1935-1941,” Folder 1, FA406, Box 33).

In 1937, smaller dolls were ordered with Miller’s approval, and the Near East Industries made arrangements for them to be marketed by Kimport, Inc., of Independence, Missouri, along with dolls manufactured by Near East Industries in Athens (Near East Foundation Records “Bulgaria Dolls 1935-1941,” Folder 1, FA406, Box 33) [6 ].

June 30, 1937

Inter Office Memo

To: Dr. Allen

From: Miss Ewald

Supplementing our conversation regarding the dolls which have been ordered from Bulgaria, may I give you copies of the catalogue and special sales advertising of my friend Mr. McKim, who is interested largely through his young daughter [Marilyn McKim].

The prices quoted are subject to varying discounts and this is the only way that Mr. McKim was able to prepare his catalogue and control same. Actually he sells the dolls at a net price the same as ours, $1.75-$2.00 for the more elaborate dolls.

I am looking forward to the arrival [sc. of the] dolls ordered from Mr. Feldmahn and I believe if he can make a really good doll at a fairly reasonable landing price, we might be able to supply some work to them.

My best wishes for a happy journey and safe landing. [Allen was returning to Macedonia from the U.S.]

Sincerely,

Rose Ewald

Near East Industries

Collectors were thrilled. One later wrote to Kimport about Penka:

“Penka from Bulgaria is one of my very nicest dolls. She was in the living room for days when everyone could see her and how the people exclaimed! Then she went to school and was part of an exhibit of Balkan countries for the benefit of some social studies classes. When my dolls go to school they are placed in the library and usually, the teachers take their classes in to see them. Everybody was thrilled over the Bulgarian. After school when I went to pack the dolls, there was a circle of·sixth grade boys looking at her and were they ever observing! They asked more questions. You might be interested in what a twelve-year-old boy would be thinking about. ‘Is that real money she is wearing?’ ‘Is the basket hand made?’ ‘Gosh, she’s a real grown up lady.’ ‘Will you look at all the braid and hand work on that skirt!’ And these are about the remarks adults have made, too. I am more than happy to have such an interesting and unusual addition to my collection.” Adeline K. Welte, Michigan.

Ewald wrote to Feldmahn on May 5, 1938 that she was particularly pleased by “the woman with faggots, the woman spinning, the bear hunter, and the priest.” Feldmahn revelled in explaining the historical background of his dolls, providing stories as Ewald had requested (Near East Foundation Records, “Bulgaria Dolls 1935-1941,” Folder 1, FA406, Box 33).

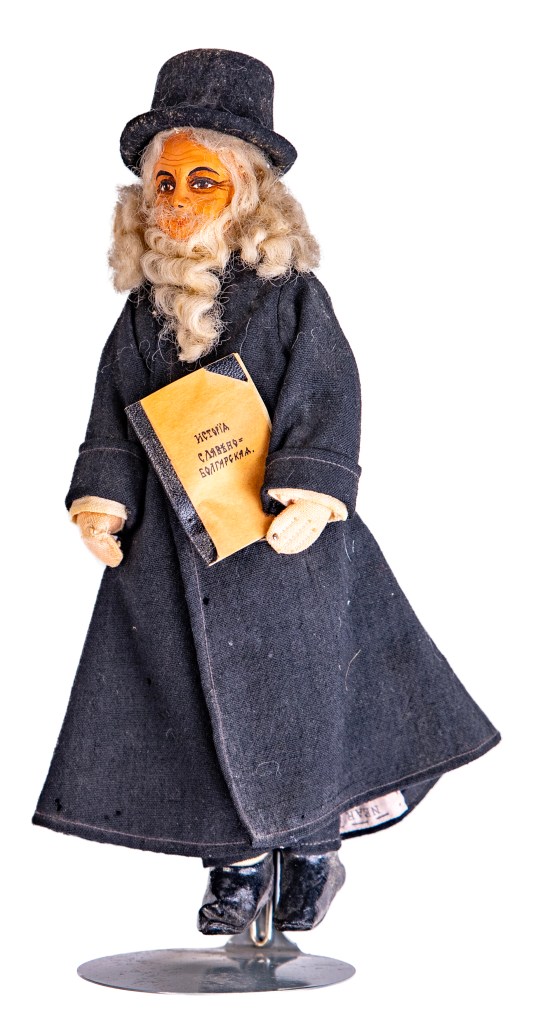

“Some of the dolls, which we sent to New York, had to represent the father of Bulgarian history—the famous monk Payssy from Hilendar. He holds in his hands a manuscript and a pen. To find a feather of the right size and not one, but for every Payssy doll, was quite a problem. Finally it was solved by a duck, belonging to our porter, which awaiting its fate to be eaten at Christmas, provided us meanwhile with the necessary writing accessories.” (Sent to Laird Archer, the resident overseas director of the Near East Foundation in Athens, November 15, 1937).

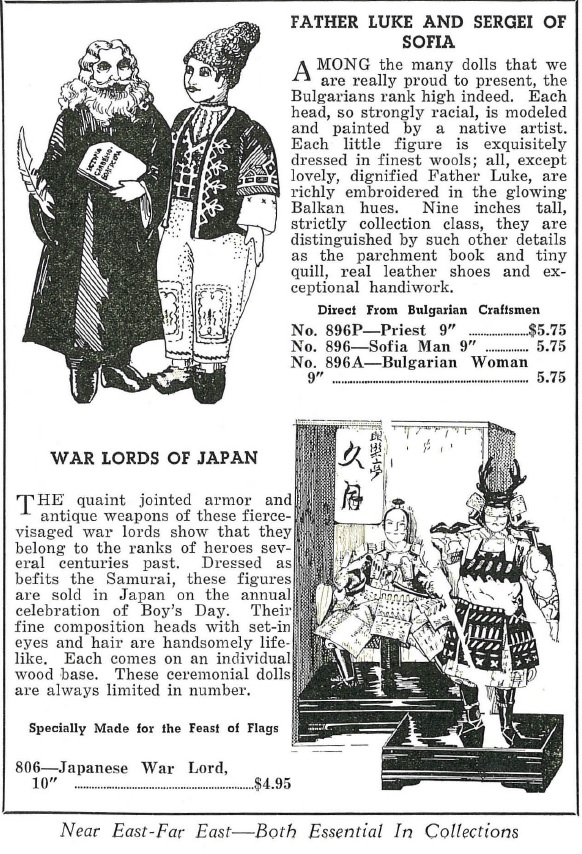

Payssy from Hilendar seems to have been too obscure a reference for Kimport, Inc.! They choked on the name and rechristened him “Father Luke” in their catalogues [7].

Bulgarian dolls were labelled as products of the Near East Foundation, 16 Iv. Vazoff str., Sofia, never of Near East Industries, and continued to be sold in America by Kimport, Inc. until the invasion of Greece by Nazi Germany made export from Sofia impossible. A final consignment was transshipped via Near East Industries in Athens, through the Suez Canal and around the horn of Africa. The fate of those dolls was uncertain.

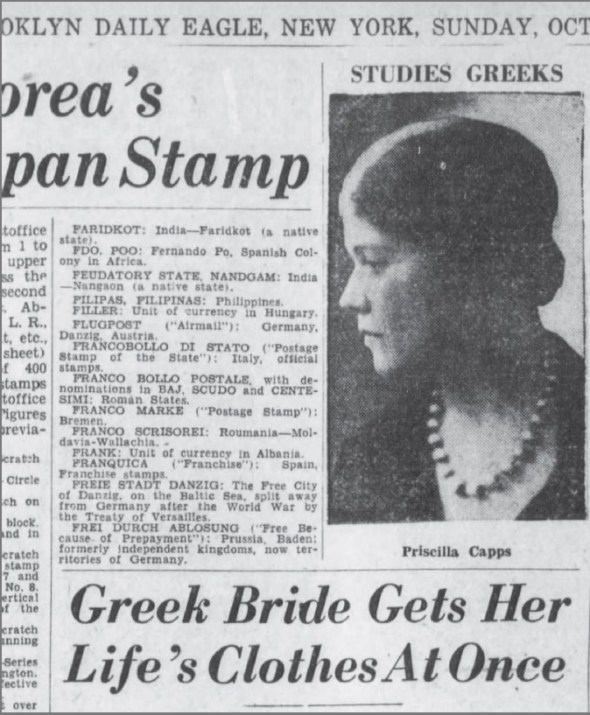

Priscilla Capps Hill, overseas director of Near East Industries, remained in Athens until the Nazi invasion. Some of her reports were reprinted in Doll Talk, and she at first seemed sanguine about the political situation in Greece, however rough conditions were. An initial report could be described by Kimport, Inc. as a “heartening letter to Near East Sponsors”:

“Well, another lot of goods has left Piraeus and we draw sighs of relief. This is the first to go since the last Export Line took stuff in June [1940] and its preparations brought life-saving earnings and encouragement to our women. All of the embroiderers have had full time work for weeks, and all our weavers. …With that really on the water, we are preparing goods for another lot hoping that the ship scheduled for November 5th will really go.” (Doll Talk, vol. 3, no. 10).

But the Italian invasion of Greece arrived a week earlier than the ship’s departure, on October 28, 1940. Near East Industries’ production then quickly changed its focus:

“February 7 [1941]—For the past two months no regular mail or documents have passed the censor. Cable and air mail must cover all. … Bulgarian dolls were sent down as far as Athens some months ago. A ship that left Athens later to sail via Suez and the Horn may have this cargo aboard and may again come safely to port. … Our army is so small many casualties will soon decrease its strength. The British are of great assistance and the new Premier [Alexandros Koryzis] will follow Metaxas’ program. He is a man of peace and such political strength that it is even possible some who opposed the Reforms will be won over to more perfect co-operation. … Furnished nurses for three hospitals at the front. Amalia made nine successful trips in charge of hospital train. … Delivered 335,000 surgica1 dressings, 15,000 garments. Giving work to 800 women with dependents.” (Doll Talk, vol. 3, no. 12).

In the United States, supplies of dolls from Athens and Sofia had largely been exhausted by the start of 1941. Capps Hill fled Athens on April 18, 1941 (the same day that Prime Minister Koryzis committed suicide), first for Cairo, then Mumbai, just as the Germans were about to enter Athens. She was especially cautious and left Athens before other Americans, since her husband Harry, director of American Express in Athens, was British.

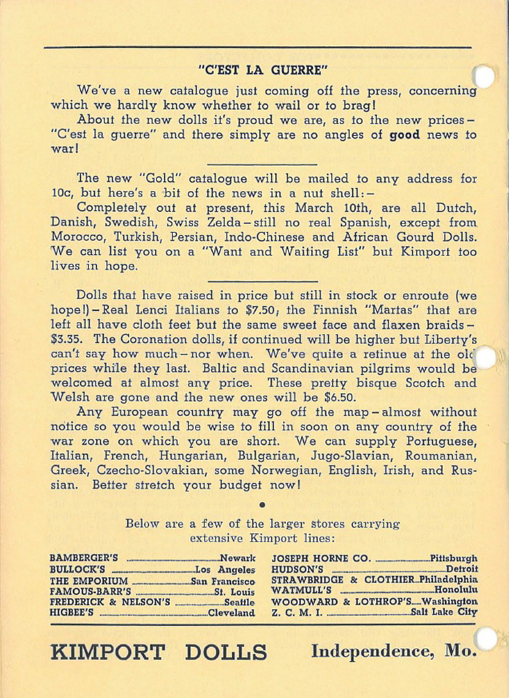

The consummate salespeople at Kimport, Inc. responded to the outbreak of war in Europe with a notice captioned “C’est la guerre”:

Several Bulgarian dolls were promoted in the same issue: Bulgarian Priest; Bulgarian Waterwitch; Bulgarian Boza-Seller; Bulgarian Bearfighter; Bulgarian Bagpiper; Boris, Bulgarian Peasant; Penka, Bulgarian Peasant; Gitta, Bulgarian Gypsy; King Assen of Bulgaria; a Bulgarian Mummer [“kukeri,” costumed men who perform rituals to scare away evil spirits].

Soon afterwards we learn just how limited were the supplies of the Sofia dolls:

“The total Bulgarian stock on hand is less than fifty dolls, but in addition to those listed at $6.50 is a ‘Mummer’ with goat head mask, cow-bell and strange costume, while at $7.50 each is a New Year’s Caroler, a Tax Collector, a Shepherd and the great 12th century Bulgarian King Assen in regal robes and early Christian symbols. His story page is especially interesting.” (Doll Talk, vol. 3, no. 6).

Other dolls listed at only $6.50 included a soldier, a woman, a priest, a bear hunter, and a gypsy woman with a baby. Kimport, Inc. was never consistent in naming its dolls.

The Nazi occupation of Greece ended the production of Bulgarian costume dolls by the Near East Foundation. But genuine sympathy for the refugee women of Greece remained at Kimport, Inc.:

“Just as this Doll Talk [April-May 1941] was being locked into its forms an appeal came in from the Near East Industries. They have helped us to get hundreds of wonderful Greek and Bulgarian dolls for you; but much, much more than that, this Charity has helped to reclaim thousands of worthy refugees in Athens. Patriots in this country are making a brave little yarn, silk and pipecleaner Evzone as a lapel gadget complete with pin on a card that tells its purpose-to “Get Behind an Evzone.” The money goes for Greek relief.

The price is 50c each, $6.00 for a dozen. Why not use them for place cards, favors and definitely wear one yourself.

Include a Bravest-Little-Soldier-in-the-World via KIMPORT DOLLS on your order.-50c.” (Doll Talk vol. 4, no. 2).

Priscilla Capps Hill wrote from Cairo on May 17, 1941: “after fifteen years of working for refugees—perhaps with a bit of feeling of superiority and patronage—I have now become one myself, with my family and all my friends. It is a strange feeling. (Near East Foundation Records, Priscilla Hill, Paris, FA406, Box 109)”

Bulgaria allied with the Axis Powers and declared war on the United States in December 1941. Feldmahn remained in Sofia until 1944, when the Red Army arrived, and then, himself a refugee for a second time, served the Near East Foundation in Beirut until his retirement [8].

In Lebanon he and his wife labored to improve the lives of the Armenian community of Anjar in the Bekaa Valley (Hoosharar, August 1, 1945, pp. 249-250).

Feldmahn died in Rochester, New York, in 1962, at the age of 82 [9]. He and Vera had moved there to live with their daughter, Alexandra, a distinguished neurologist. Αιωνία η μνήμη σου.

Dedication and Credits

I dedicate this post to the memory of Mr. Anatol Voeikov, a Russian émigré who found his home in Macedonia.

As ever, I am grateful to the staff of the Rockefeller Archive Center in Sleepy Hollow, particularly to Archivist Renee Pappous, who found the photograph of Feldmahn for me and pointed the way to much of the archival material on which I here draw, and to Archivist Bob Clark. The photograph of Feldmahn is here reproduced with permission of the Rockefeller Archives Center. I thank Jen Sacher for her help in Sleepy Hollow, as acknowledged above, and Natalia Vogeikoff for her reading of my drafts. Antonis Godis helped with research. Finally, I am grateful to Shannan Stewart for finding scans of early issues of Doll Talk.

I dedicate this post to the memory of Mr. Anatol Voeikov, a Russian émigré who found his home in Macedonia.

As ever, I am grateful to the staff of the Rockefeller Archive Center in Sleepy Hollow, particularly to Archivist Renee Pappous, who found the photograph of Feldmahn for me and pointed the way to much of the archival material on which I here draw, and to Archivist Bob Clark. The photograph of Feldmahn is here reproduced with permission of the Rockefeller Archives Center. I thank Jen Sacher for her help in Sleepy Hollow, as acknowledged above, and Natalia Vogeikoff for her reading of my drafts. Antonis Godis helped with research. Finally, I am grateful to Shannan Stewart for finding scans of early issues of Doll Talk.

Endnotes

[1] For information about Feldmahn’s activities in Bulgaria as representative of the Russian Red Cross, see the following files of the League of Nations: League of Nations. File C1437/333/Rr.404/2/10/1 – Russian Refugees – Relations with L. E. Feldmahn, Chairman, Delegation of the Russian Red Cross [old organisation] in Bulgaria (https://archives.ungeneva.org/russian-refugees-relations-with-l-e-feldmahn-chairman-delegation-of-the-russian-red-cross-old-organisation-in-bulgaria); Russian Refugees – Mr. Gehri, Representative of the High Commissioner in Sofia – Note on the interview he had with Mr. Feldmahn and Mr. Antonoff, from the Russian Red Cross of Constantinople (https://archives.ungeneva.org/les-refugies-russes-m-gehri-representant-du-haut-commissaire-a-sofia-note-sur-lentretien-quil-a-eu-avec-m-feldmahn-et-avec-m-antonoff-de-la-croix-rouge-russe-de-constantinople/download).

[2] One year later Harold B. Allen, Near East Foundation Director of Education in Salonica and Laird W. Archer, the resident overseas director of the Near East Foundation in Athens, reported: “Leon H. Feldmahn, is a Russian engineer who has been in our service for some ten years and in the service of the Russian Red Cross (Old Regime). He is thoroughly versed in our ideas and policies, and has shown himself especially capable in adapting them to local conditions within local means.” (“Report of the Overseas Executives for June, 1937,” p. 17, Dockets of Board of Directors Meetings, July 1, 1937, FA1305_B3).

Feldmahn’s formal association with Near East Relief began in 1927, after its executive committee had voted up to $5000 for Bulgarian relief on May 26, 1926 “in response to the appeal of Minister Radeff and the Metropolitan of Sofia,” and had added that “as much as practicable of it shall be in the form of used clothing rather than in cash.” Feldmahn is first mentioned by name in minutes of September 29, 1927, in conjunction with “250 bales of old clothing, 50 bags of old shoes,” being shipped for use in Bulgaria. The project was a success. On April 7, 1930, Edward C. Miller, comptroller of the Near East Foundation, could write to Archer that “the Bulgarian old clothes industries are practically self-sustaining,” even recommending that Feldmahn be authorized “to disburse $500 in the promotion of playgrounds in Sofia in collaboration with the Bulgarian Save the Children Union.” On January 8, 1932, Archer then reported that Feldmahn had extended his program by using his playground staff to support working mothers and their families. “Public Health and Playground Project,” Near East Foundation Annual Reports, 1931-1934, p. 72-a, FA1305_B2.

[3] The Evening Star of Washington, D.C., December 18, 1930, p. 32. Feldmahn was born Leontiy Evgenievich Von Feldman (Фон Фельдман Леонтий Евгеньевич) on November 1, 1879, his wife as Vera Pavlovna Feldman ( Фельдман Вера Павловна) on May 19, 1901.

[4] The earliest reference to Near East Foundation doll manufacture in Sofia appears to be in The Evening Star of Washington, D.C., December 18, 1930, p. 32. I thank Antonis Godis for bringing this article to my attention. See also a report dating to mid-1932: “Private orders are taken, for underwear, shoes made to measure, Bulgarian character dolls, fancy Bulgarian dresses, etc.” (L. E. Feldmahn, “Clothing Reconditioning Industries, Sofia, Bulgaria,” Near East Foundation: Basic Project Reports, p. 120, FA1305_B3). Near East Industries began to manufacture dolls in Athens about the same time (J.L. Davis and N. Vogeikoff-Brogan, “Priscilla Capps Hill and the Near East Industries,” in In the Name of Humanity: American Relief Aid in Greece, 1918-1929 [Athens 2023], p. 87).

[5] Feldmahn in his reply expressed reservations concerning the cost of shipping to the U.S., or even to Greece, while noting that in 1936 he had sold 1500 dolls (February 6th 1937, in Near East Foundation Records, “Bulgaria Dolls 1935-1941, Folder 1,” FA406, Box 33)

[6] For Kimport, Inc. and Near East Industries in Athens, see https://nataliavogeikoff.com/2017/07/01/dollies-and-doilies-priscilla-capps-hill-and-the-refugee-crisis-in-athens-1922-1941/. Kimport was already marketing dolls from the Near East Industries in Athens by the time its first issue of volume 1 of Doll Talk for Collectors was published in 1936. (Internal information allows it to be dated.) The McKims began their doll business in 1932 in the wake of a trip to Paris (Doll Talk, vol. 1, no. 9, p. 1).

[7] The book he carries is, however, Payssy from Hilendar’s Istoriya Slavyanobulgarskaya (1762). Our own “Father Luke” dolls in the ASCSA Archives are missing their duck feather pen, but it was present in the illustration in Doll Talk, vol. 2, no. 7, when he was advertised early in 1939.

[8] Alexandra Feldmahn, Public Health, Medicien, and Sanitation in Bulgaria, Prepared for the Surgeon General’s Office of the U.S. Army, Near East Foundation, 1943. Feldmahn, who had left Bulgaria, wrote the report on behalf of her father at the age of 22.

[9] The Feldmahns are buried in the cemetery of the Holy Trinity Russian Orthodox Monastery in Jordanville, Herkimer County, New York.

Dear Jack,

Many thanks for another wonderful piece!

I was fascinated in costumed dolls as a child. I had a friend whose older brother was in the Navy and brought her costumed dolls from every port he sailed to. Ebay has several Kimport catalogs listed.

best, Judith Levine

Thanks Judith. Lot of Kimport catalogues appear on EBay, but rarely the early ones.