EUZONES AND POETRY: JAMES MERRILL, GREEK LOVE, AND THE MAKING OF A PULITZER-PRIZE WINNER

Posted: October 15, 2015 Filed under: American Poetry, American Studies, Archival Research, Biography, Book Reviews, Philhellenism | Tags: Charles Shoup, James Merrill, Kimon Friar, Langdon Hammer 4 CommentsBy Jack L. Davis

Jack L. Davis, Carl W. Blegen Professor of Greek Archaeology at the University of Cincinnati and a former director of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (2007-2012), here reviews Langdon Hammer’s recent biography of American poet James Merrill, focusing on the poet’s house in Athens. Merrill, who lived much of his life in Greece, left his house in Kolonaki to the American School as a bequest.

In 1945 a young undergraduate student at Amherst College met and was immediately captivated by a temporary English instructor, who became his first lover. Kimon Friar, the professor, drew James Merrill, at 20 years of age already a promising writer, into an “erotic literary apprenticeship” that was influenced both by ancient Athenian concepts of pederastia as well as the life and works of Constantine Cavafy, the Alexandrian poet. Along the way, Friar taught Merrill demotic Greek. Merrill had a gift for tongues, later even picking up Japanese as a tourist; with a fine Classical education as a foundation, he learned to speak Greek properly and deliberately, and enjoyed the language’s sound.

Friar also enticed Merrill to visit Greece, writing to him in 1946: “Here in Greece I have found another world, another planet, one which you will also recognize as your spiritual home. It is here for our colonizing.”

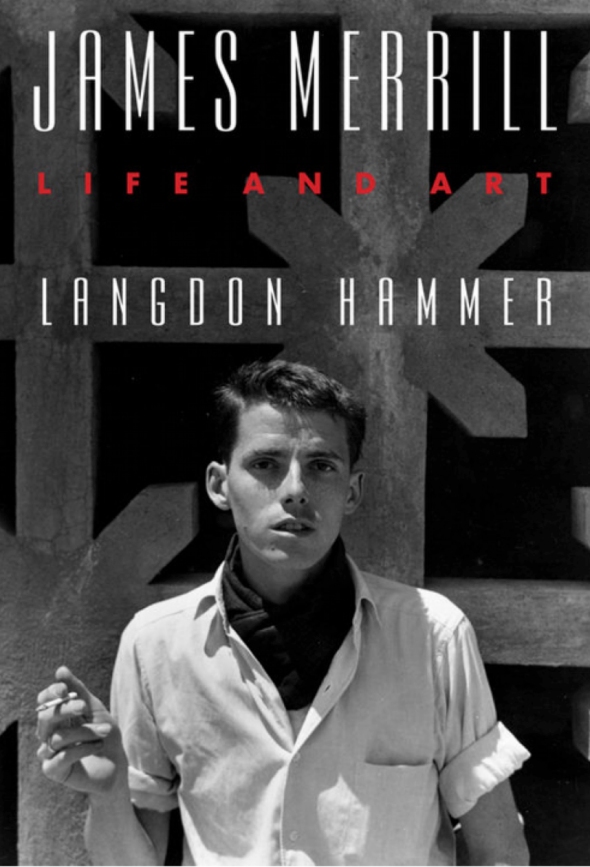

Merrill’s life is extensively documented, most prominently in an enormous archive (175.5 linear feet) at Washington University in St. Louis. The Gennadius Library of ASCSA holds his correspondence with friends Mimi Vasilikou, his Greek translator, and her husband Vassilis Vassilikos, author of the political novel “Z” (http://www.ascsa.edu.gr/index.php/archives/vassilis-vassilikos-papers). Merrill also published A Different Person (1994), a biography of his coming of age in Rome, in the year before his death — and more recently there have been memoirs produced by friends. But Langdon Hammer’s James Merrill: Life and Art is the first truly comprehensive examination of his life and work, from birth to death (http://www.amazon.com/James-Merrill-Life-Langdon-Hammer/dp/0375413332).

In 1950 Merrill first visited Greece, Athens and then Poros, where Friar had holed up to translate Nikos Kazanzakis’s The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel. But it was only in 1959 that Merrill began to spend considerable amounts of time in Athens, after his affair with Friar had ended, in the company of his life-long partner David Jackson. Architect and designer Charles Shoup introduced them to his circle of expatriate friends, including Tony Parigory, an Alexandrian antiques dealer whose friendship Merrill particularly cherished. [Merrill was captivated by the idea of Alexandria, later writing that he might as well have been born on the Corniche as in New York City.]

From Shoup he also learned the “protocols and possibilities of homosexuality in Greece.” Foreigners offered Greeks, Merrill joked, “l’entrée des artistes,” and permitted them to preserve “the masculine ideal.” Athens was a world in which “beauty and gay desire were for once not forbidden subjects.”

When I assumed the post of director of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens in 2007, I learned for the first time that our School owned Merrill’s former residence at 44 Athenaion Ephebon, a street name that Merrill and Jackson found amusing (“The Street of Athenian Teenage Boys”). The property had been transferred to ASCSA in January 1995, one month before Merrill’s unexpected death from complications relating to AIDS.

Today “Merrill House” serves as the residence of John Camp, director of the ASCSA’s Athenian Agora Excavations. John recently told me how it was that ASCSA acquired the property.

[Merrill] was a family friend, particularly of my mother’s. He and David J. lived in Stonington, Connecticut and we lived in Watch Hill, R.I, about 5 miles away and we saw them fairly regularly there. My mother and they also spent a few winters in Key West, and there was the Athens connection as well. Mostly we played bridge and hung out; no ouija board. When he moved back to the States I rented his house for several years, until 1985. He rented it to other friends once I moved into Loring west as Mellon [Professor of ASCSA], and because of our associations decided to leave it to the School in his will.

James Ingram Merrill (1926-1995) was a (some thought the) leading poet of his generation. In 1977 he won a Pulitzer prize for his Divine Comedies, a book of Dantesque poems including The Book of Ephraim, first in a trilogy based on Ouija board séances that he held with Jackson — many in 44 Athenaion Ephebon. Although his talents were immediately validated by peers and reviewers, he continued to struggle throughout his life against the legacy of a childhood dominated by a confident, successful father (the founder of the Merrill Lynch brokerage house), the need to adjust to a broken home and a blended family at age 13, and the impossibility of coping with a mother who loved him dearly, but could not come to terms with his homosexuality. She outlived him and never did.

Langdon Hammer’s biography makes no secret of Merrill’s promiscuity, which was central both to his life and art. He loved men of all sorts — sometimes more than one at a time. He looked to “sex cures” as a defense against the depression that generally followed completion of a major project: once, on returning to Greece from the U.S, he recorded 30 encounters in 30 days with 16 different partners. But it was falling in and out of love, not the sex act itself, that promoted his creativity.

In 1964, on his first day in 44 Athenaion Ephebon, he would pick up a handsome soldier in Omonia Square and bring him home. Stratos Mouflouzelis, nephew of Yiorgos Mouflouzelis, the singer of rebetiko, would become a significant part of his life, a lover and a muse.

Merrill believed that the gap between his Greek and American worlds narrowed as the years passed. And it did in very concrete ways: he even moved a Greek lover’s wife and children into his Connecticut house. But he continued to visit Greece until 1992.

“Merrill House” is far from grand. It was and is the very antithesis of the elegantly furnished apartment in Stonington that he and Jackson shared — a three-story Victorian. 44 Athenaion Ephebon was, nevertheless, of great significance to Merrill, while its neighborhood vibrates in his well-known poem “Days of 1964” (the first of a series of poems consciously modeled on Cavafy’s “Days of 1896” and its sequels).

In “Days of 1964” Merrill describes walking through the Kolonaki Friday market on Xenokratous St., after catching the eye of his maid, off to supplement her income by working as a prostitute.

Startled mute, we had stared – was love illusion? –

And gone our ways. Next, I was crossing a square

In which a moveable outdoor market’s

Vegetables, chickens, pottery kept materializing

Through a dream-press of hagglers each at heart

Leery lest he be taken, plucked,

The bird, the flower of that November mildness,

Self lost up soft clay paths, or found, foothold,

Where the bud throbs awake

The better to be nipped, self on its knees in mud -–

Here I stopped cold, for both our sakes;

And calmer on my way home bought us fruit.

His letters bring the house alive too. Merrill lived on the ground floor, Jackson on the second, but his inner sanctum was a converted former laundry room on the roof — the roof then as now also a focus for parties. After returning to Athens from the United States, Merrill wrote to David McIntosh, the painter:

It’s funny how one reassumes a whole life — or half a life. The street-cries. The ballet of the telephone extension cord, trying to get it up and down the spiral stairs without turning into Laocoön … My study is what I adore, so high and yet so humble — here I feel really free + alone.

Some of his most highly acclaimed work emerged from that cramped space.

The New Yorker’s reviewer (April 13, 2015) called Hammer’s book “extraordinary.” That it is. The New York Times’ reviewer (April 14, 2015) followed suit, commenting that “Mr. Hammer’s book is something close to brilliant.” But he also remarked that it “would have benefited from committed liposuction” and that it is “punishingly long.” Also true.

James Merrill: Life and Art has an encyclopedic density comprehensible only in an academic book. (Hammer is, after all, chair of Yale’s English department). Which is to say that you will enjoy this book only if you are willing thoroughly to surrender yourself both to Merrill’s poetry and life. And it does require dedication: Merrill’s work is symbolic, metaphysical, and richly autobiographical. Reading demands deep knowledge of his being and that is what Hammer gives us.

Over the summer, as I was reading James Merrill, I came to experience Merrill the man, the complexity of his personality and its sometime contradictory nature. Bob Pounder, former Secretary of ASCSA and Assistant to the Director (1970-75), knew Merrill well and recently described him to me as “… the most brilliant, perplexing, generous, difficult, wonderful person I’ve ever known.” He is someone I might have met in Athens, whom I wish I had met, but did not. I am grateful to Hammer for introducing me at last to his life and art.

JAMES MERRILL: Life and Art

By Langdon Hammer

New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2015

Illustrated. 913 pages.

Most excellent review. Thanks for introducing me to JM, Jack and Natalia.

Fine review, Jack. Fascinating stuff, as usual, especially when it involves the American School and Athens in the post-WW II period.

Dear Natalia,

Whenever your blog comes, I binge out and read all the links. Days later I surface and that’s how I got to the Nancy Mitford piece. I once asked Homer about her and he wrote the most vehement letter I every received. Basically saying that she was uneducated and opinionated and stubborn. He then proceeded to blast people who preferred picturesque ruins to the original reality. Unfortunately, I have lost my copy of the letter but a copy must be in the Mayer House file on Homer, which I hope is in Princeton if you don’t have it? The letter certainly read as if he had met her.

My mother once met Nancy Mitford and disliked her. I wish I had been a fly on that wall when those two formidable women went at each other. It was nice to see that Homer agreed!

Keep up the good work. Whatever happened to your piece on Mayer House?

All best,

Ludmila

Dear Ludmila: Thank you for your encouraging words. Your correspondence is now in the School’s Archives in Athens. I will check. I will also check H.A.T’s correspondence because a lot of times he kept copies of his outgoing correspondence. As for the Mayer House, it’s in the line, I have built up a file with information about it (and Clara Mayer, of course). I hope you enjoy today’s piece about the last days of the Blegens and the Hills. With best wishes, Natalia