FULBRIGHTING IN POST-WW II GREECE (1952-1953)

Posted: November 2, 2017 Filed under: American Studies, Archaeology, Archival Research, History of Archaeology, Modern Greek History | Tags: Arnold Whitridge, Carl W. Blegen, Fulbright Foundation in Greece, George R. Stewart 4 CommentsThe Surplus Property Act of 1944 was an act of the U.S. Congress which allowed the Secretary of State to enter into agreements with the governments of foreign countries for the disposal of surplus American property (mostly WW II scrap) abroad. The Fulbright Act, as it is better known today, became a pioneering platform for educational exchanges between the U.S. and a large number of countries, thanks to an amendment introduced by a young Democratic Senator from Arkansas, J. William Fulbright, in 1945. The amendment allowed the sale of surplus property (e.g., airplanes and their spare parts, arms and ammunition) to foreign countries in exchange for “intangible benefits.” One of those benefits, at the insistence of Senator Fulbright, who had been a Rhodes Scholar as a young man, involved the international exchange of scholars. Since foreign governments did not have enough dollars to pay for the purchase of surplus material, the Act allowed them to use their local currencies to pay the expenses of American scholars studying in those countries. Fulbright strongly believed in the transformative value of educational exchanges, that they could “play a major role in helping to break down mutual misunderstandings,” and contribute to world peace. On August 1, 1946, President Truman signed the Fulbright bill into law.

Graveyard of American jeeps after WW II

Senator Fulbright

The first European country to sign the Fulbright Agreement was Greece, on April 23, 1948. The American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or the School herefafter) with its superb reputation, was one of the immediate beneficiaries of the bi-national agreement. The School claimed that it was the only place of higher learning where American students could apply for research grants to carry out advanced work in classics and archaeology. “It is of course possible for Americans to enroll in the School of Liberal Arts in the University of Athens; but the lecture courses are largely theoretical, library and other facilities are sadly inadequate, and the language problem constitutes a difficult hurdle” argued archaeologist Carl W. Blegen to Gordon T. Bowles of the Conference Board of Associated Research Councils on September 15, 1948 (AdmRec 705/1, folder 1). Blegen, Professor of Archaeology at the University of Cincinnati, had been appointed as Director of the American School for a year (1948-1949). Having served the interests of the School for a long time, Blegen naturally cared first and foremost for the institution’s well-being. Blegen and others, such as Homer A. Thompson, Director of the Athenian Agora Excavations, saw in the Fulbright Act a new source of income to finance the School’s operations and, especially, the research that was carried out in the Athenian Agora. I have written elsewhere about the curious entanglement of the American School with the Fulbright Foundation in the early years of the program’s implementation, and I will be talking more about it on November 30th at Cotsen Hall in a joint event organized by the ASCSA and the Fulbright Foundation on the occasion of its 70th anniversary. Read the rest of this entry »

An African American Pioneer in Greece: John Wesley Gilbert and the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1890-1891.

Posted: August 1, 2017 Filed under: American Studies, Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Classics, History of Archaeology, Mediterranean Studies | Tags: Andrew Fossum, Carleton Brownson, Charles Waldstein, Eretria, John Pickard, John Wesley Gilbert, Rufus B. Richardson 20 CommentsPosted by John W. I. Lee

John W. I. Lee, Professor of History at the University of California, Santa Barbara, here contributes an essay about John W. Gilbert, the first African-American student to participate in the Regular Program of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA) in 1890-1891. Lee is writing a book about John Wesley Gilbert, the early history of the ASCSA, and the development of archaeology in Greece.

In his official report to the Managing Committee of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or the School hereafter) for academic year 1890-1891, Director Charles Waldstein praised students Carleton Brownson, Andrew Fossum, John Gilbert, and John Pickard, who had “proved themselves serious and enthusiastic” throughout the year. Waldstein went on to describe the School’s 1891 excavations at ancient Eretria on the island of Euboea. While Fossum and Brownson excavated Eretria’s theater, Pickard and Gilbert “undertook the survey and careful study of all the ancient walls of the city and acropolis, and will produce a plan and an account which… will be of great topographical and historical value.”

Waldstein’s report gives no indication that one of the students, John Gilbert, was African American—the first African American scholar to attend the ASCSA. With the passage of time, memory of Gilbert’s pioneering contribution was forgotten at the School, until Professor Michele Valerie Ronnick of Wayne State University searched for him in the ASCSA Archives in the early 2000s. Ronnick’s work on Gilbert, featured in the School’s Ákoue Newsletter, forms the foundation of my research.

John Wesley Gilbert. Photo: Daniel W. Culp, Twentieth Century Negro Literature (1902)

John Wesley Gilbert was born about 1863 in rural Hephzibah, Georgia; his mother Sarah was enslaved. After Emancipation, Sarah took her young son to the nearby city of Augusta. From childhood Gilbert thirsted for learning. An 1871 Freedman’s Bank register bearing his signature gives his occupation as “go to school to Miss Chesnut.” Read the rest of this entry »

Communism In and Out of Fashion: The American School of Classical Studies at Athens and the Cold War

Posted: September 1, 2016 Filed under: American Studies, Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, History of Archaeology, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism, Women's Studies | Tags: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Emily Grace Kazakevich, Homer A. Thompson, Ida Thallon Hill, Jane Harrison, Kevin Andrews, Robert Oppenheimer, Robert Scranton 4 CommentsPosted by Jack L. Davis

Jack L. Davis, Carl W. Blegen Professor of Greek Archaeology at the University of Cincinnati and a former director of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (2007-2012), here contributes an essay about attitudes of the ASCSA and its members toward Communists and Communism in the 20th century.

“Feeling they were witnessing the demise of capitalism, many writers moved left, some because their working class origins helped them identify with the dispossessed, others because they saw socialism or Communism as the only serious force for radical change, still others because it was the fashionable thing to do; they went where the action was.”

Morris Dickstein, Dancing in the Dark (2009), pp. 16-17.

In 1974, when I first arrived at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or the School hereafter), we youngsters were told that we should not express our political views in public. The ASCSA’s institutional mission might be hurt, were it perceived not to be neutral. In September 1974 that was certainly a reasonable position for the ASCSA to assume. Yet I was curious. In 1974, I was myself radicalized, and had definitely headed left. I could not condone U.S. policy in respect to the Junta, or the suppression of the Left in Greece. Could I say nothing? Had the ASCSA always maintained a position of strict neutrality? Or were its postures more convenient than sincere? Read the rest of this entry »

In 1974, when I first arrived at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or the School hereafter), we youngsters were told that we should not express our political views in public. The ASCSA’s institutional mission might be hurt, were it perceived not to be neutral. In September 1974 that was certainly a reasonable position for the ASCSA to assume. Yet I was curious. In 1974, I was myself radicalized, and had definitely headed left. I could not condone U.S. policy in respect to the Junta, or the suppression of the Left in Greece. Could I say nothing? Had the ASCSA always maintained a position of strict neutrality? Or were its postures more convenient than sincere? Read the rest of this entry »

On Communism and Hellenism: An Archaeologist’s Perspective

Posted: March 1, 2016 Filed under: American Studies, Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, History, History of Archaeology, Intellectual HIstory, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism | Tags: Alison Frantz, American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Carl W. Blegen, Communism, Donald C. McKay, Hellenism 3 CommentsPosted by Despina Lalaki

Despina Lalaki holds a PhD in Historical Sociology from the New School university while she currently teaches at the The New York City College of Technology-CUNY. The essay she contributed to ‘From the Archivist’s Notebook’ is largely an excerpt from her article “On the Social Construction of Hellenism: Cold War Narratives of Modernity, Development, and Democracy for Greece,” in The Journal of Historical Sociology, 25:4, 2012, pp. 552-577. Her essay draws inspiration from an unpublished manuscript by archaeologist Carl W. Blegen, titled “The United States and Greece” and written in 1946-1948.

Carl W. Blegen (1887-1971) is one of the most eminent archaeologists of the Greek Bronze Age. Nevertheless, he intimately knew Modern Greece, too. In 1910, at the age of twenty-three, he first visited the country as a student of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (hereafter ASCSA), and by the time of his death in 1971 he had made Greece his home and his final resting place, having experienced first hand the land and its people in the most troublesome moments of their modern history. In 1918, for instance, he participated in the Greek Commission of the American Red Cross, assisting with the repatriation and rehabilitation of thousands of refugees who during the war had been held as prisoners in Bulgaria. During WWII, he was recruited by the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) to head the Greek desk of the Foreign Nationalities Branch (FNB) in Washington D.C., which was following European and Mediterranean ethnic groups living in the United States and recording their knowledge of political trends and conditions affecting their native lands.

J. W. Foster (left) and Carl W. Blegen (right) standing at the headquarters of the Allied Mission for Observing the Greek Elections (AMFOGE), 1946. Photo by Nat Farbman. The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images/Ideal Image.

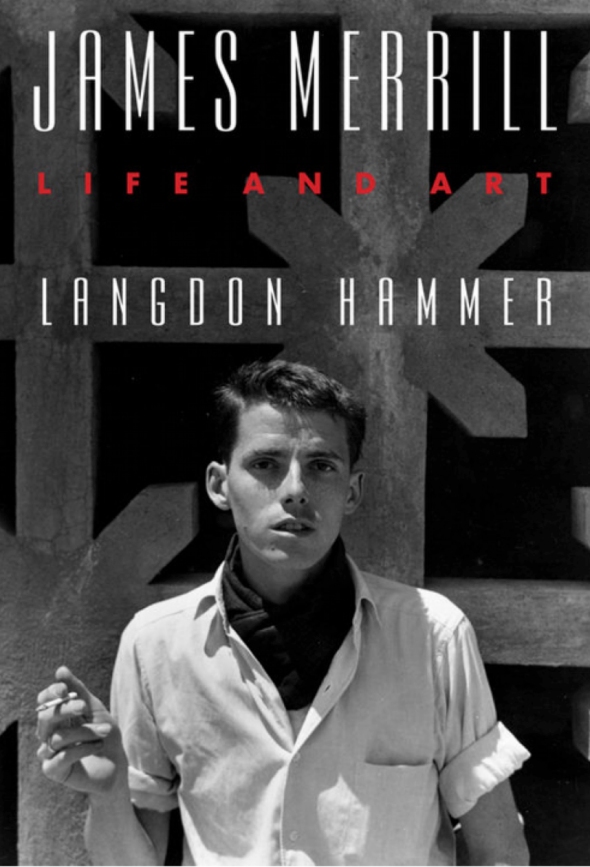

EUZONES AND POETRY: JAMES MERRILL, GREEK LOVE, AND THE MAKING OF A PULITZER-PRIZE WINNER

Posted: October 15, 2015 Filed under: American Poetry, American Studies, Archival Research, Biography, Book Reviews, Philhellenism | Tags: Charles Shoup, James Merrill, Kimon Friar, Langdon Hammer 4 CommentsBy Jack L. Davis

Jack L. Davis, Carl W. Blegen Professor of Greek Archaeology at the University of Cincinnati and a former director of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (2007-2012), here reviews Langdon Hammer’s recent biography of American poet James Merrill, focusing on the poet’s house in Athens. Merrill, who lived much of his life in Greece, left his house in Kolonaki to the American School as a bequest.

In 1945 a young undergraduate student at Amherst College met and was immediately captivated by a temporary English instructor, who became his first lover. Kimon Friar, the professor, drew James Merrill, at 20 years of age already a promising writer, into an “erotic literary apprenticeship” that was influenced both by ancient Athenian concepts of pederastia as well as the life and works of Constantine Cavafy, the Alexandrian poet. Along the way, Friar taught Merrill demotic Greek. Merrill had a gift for tongues, later even picking up Japanese as a tourist; with a fine Classical education as a foundation, he learned to speak Greek properly and deliberately, and enjoyed the language’s sound. Read the rest of this entry »