Professors to the Rescue: Americans in the Aegean at the End of the Great War, 1918-1919.

Posted: January 3, 2019 Filed under: Archival Research, Biography, History of Archaeology, Philhellenism | Tags: A. Winsor Weld, American Red Cross Greek Commission, Cyril G. Hopkins, Edward Capps, Henry B. Dewing, Horace S. Oakley 4 Comments“Islands and coast Asia Minor still crowded with refugees. Stop. Number there still to be repatriated estimated three hundred thousand. Stop. We are maintaining three stations in Mytilene district clothing alone being available, but food urgently needed. Stop. Above statements based on personal inspection this Commission. Stop. We recommend that work in Aegean be immediately extended to other islands like Chios, Samos and to opposite coast which can be reached by sea transport which can be secured by Greek governments. Stop.”

The text quoted above is a small portion of a long telegram (47 lines) that Colonel Edward Capps sent to Harvey D. Gibson, member of the American Red Cross War Council in Paris, on December 12, 1918 (NACP, Greece, ARC Commission to, 964.62/08). The telegram reported the activities of the American Red Cross (ARC hereafter) since arrival of its Greek Commission in Athens on October 23rd.

This is not the first time I am writing about the activities of the ARC in Greece. In 2011, together with Jack L. Davis, then Director of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or the School hereafter), we organized and subsequently published the proceedings of a conference titled Philhellenism, Philanthropy, or Political Convenience: American Archaeology in Greece (Princeton 2013). Davis’s paper, “The American School of Classical Studies and the Politics of Volunteerism,” discussed the involvement of members of the ASCSA, through enlistment in the Greek Commission of the ARC, in humanitarian aid in eastern Macedonia, as well as in the repatriation of Greek citizens who had been taken as hostages to Bulgaria. Later in 2015, on the occasion of the centenary of the Battle of Gallipoli, I was invited to participate in a conference about The First World War in the Mediterranean and the Role of Lemnos, with a paper that discussed the humanitarian activities of the ARC Greek Commission in the eastern Aegean at the end of the Great War.

This is not the first time I am writing about the activities of the ARC in Greece. In 2011, together with Jack L. Davis, then Director of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or the School hereafter), we organized and subsequently published the proceedings of a conference titled Philhellenism, Philanthropy, or Political Convenience: American Archaeology in Greece (Princeton 2013). Davis’s paper, “The American School of Classical Studies and the Politics of Volunteerism,” discussed the involvement of members of the ASCSA, through enlistment in the Greek Commission of the ARC, in humanitarian aid in eastern Macedonia, as well as in the repatriation of Greek citizens who had been taken as hostages to Bulgaria. Later in 2015, on the occasion of the centenary of the Battle of Gallipoli, I was invited to participate in a conference about The First World War in the Mediterranean and the Role of Lemnos, with a paper that discussed the humanitarian activities of the ARC Greek Commission in the eastern Aegean at the end of the Great War.

My paper, titled “Professors to the Rescue: Americans in the Aegean at the End of the Great War, 1918-1919,” was published in the proceedings of the conference in 2018. Since the publication, because of its modern historical focus, will hardly reach the archaeological community, I decided to post a version of my paper, enhanced with more images, here. The story to be told is another, unknown chapter in the history of the American School; it also tells the story of a number of people, such as A. Winsor Weld and Horace S. Oakley, who, strangers at first to Greece, turned into philhellenes and life-long supporters of the American School.

The Greek Commission

The ARC’s mission to Greece was organized in June and July of 1918 in response to an appeal from the Greek Red Cross. From the time that America entered the war in 1917, the ARC, with the endorsement of President Wilson’s government, had sent several commissions to Europe to provide military and civilian relief in England, France, Italy, Belgium, and Serbia. The Greek Commission was headed by Edward Capps (1866-1950), professor of Classics at Princeton University and newly appointed chairman of the School’s Managing Committee, a position he would hold for twenty years (1918-1939).

“There came from America to do the work 103 persons (60 men and 43 women), and several others were recruited in Europe. They enlisted in the service of the American Red Cross from all parts of the United States, and represented all manner of occupations and professions. There were business men, lawyers, bankers, physicians, preachers, teachers, farmers and mechanics, and among the women, trained nurses, stenographers and social workers. The authority of the Commission was vested in the Commissioner, who held the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, and seven Deputy Commissioners with the rank of Major.” Thus Capps described the composition of his team in his final report at the conclusion of their mission (Capps 1919, p. 11).

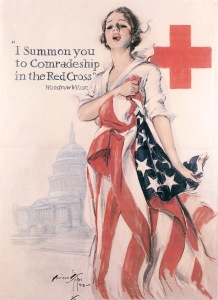

The front image from Julia Irwin’s book, The American Red Cross and a Nation’s Humanitarian Awakening (Oxford2013).

Henry B. Dewing (1882-1956), assistant professor of Classics at Princeton, most likely Capps’s personal choice, was appointed Secretary of the Commission. It is not clear when and how it was decided that Edward Capps would lead the ARC Greek Commission. The fact that he had been a colleague of Woodrow Wilson at Princeton University must have played some role. But it was not the only reason. The ARC had created a separate department, the Insular and Foreign Division (IFD), to reach out to the thousands of Americans who resided abroad, either as employees of the State Department or working for various American corporations, institutions, and organizations (Irwin 2013, p. 76). (For information about the activities of the ARC during Wilson’s presidency I have relied on Julia Irwin’s excellent book, Making the World Safe: The American Red Cross and a Nation’s Humanitarian Awakening, [Oxford 2013].)

That Capps had access to an operating base in Greece (i.e., the American School) must have given him a leg up in the selection process. In addition, the staff of the School in Athens, Bert Hodge Hill, director since 1906, and Carl Blegen, secretary since 1912, shared a deep knowledge of Greece (its geography, language, customs) and, above all, they were well connected. “An essential depository of local experience,” the School could (and would) act as a buffer to a group of newcomers ignorant of Greek realities (Hatzivassiliou 2013, p. 18).

The Greek Commission, in addition to Capps and Dewing, also included seven deputy commissioners:

Clifford W. Barnes, Chicago. Minister (1864-1944)

Carl E. Black, Jacksonville, Illinois. Surgeon (1862-1944)

Cyril G. Hopkins, Urbana, Illinois. Professor of Agronomy (1866-1919)

Alfred F. James, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Businessman (1870-1959)

Horace S. Oakley, Chicago, Illinois. Lawyer (1861-1929)

Samuel J. Walker, Chicago, Illinois. Physician (unknown dates)

A. Winsor Weld, Boston, Massachusetts. Businessman (1869-1956)

The Greek Commission at the ARC Headquarters at 19 Kephissias Street. First row, left to right: Clifford Barnes, Samuel Walker, Edward Capps, ?, Winsor Weld, and Carl Black. Clifford W. Barnes Papers, Chicago History Museum.

We do not know the selection criteria for the deputy commissioners and how much say Capps had in the selection process. That the majority of them had some connection with the state of Illinois, Capps’s home state, makes me suspect that he was involved in the selection of the deputy commissioners, and probably already knew some of them personally. Capps had been born in Jacksonville, Illinois in 1866, received his B.A. from Illinois College (1887), his Ph.D. from Yale (1891), and had taught at the University of Chicago before he moved on to Princeton. With the exception of Dewing, who was in his mid 30s, the rest of the officers were mature men in their early 50s with families and established careers. Each commission must have had representatives from a number of professions. Naturally, doctors and nurses, but also ministers, bankers, and lawyers were highly desirable members, as this telegram to Horace Oakley reads: “… this commission should include lawyer and you have been suggested as eminently fitted for this position” (Newberry Library, Horace S. Oakley Papers, Alfred James to Oakley, Sept. 3, 1918).

ARC Commissioner Edward Capps posing on the balcony of the ARC head quarters. What do the Greek letters stand for? Find the answer below.

A New Elite Emerges

While for the younger people personal development and career opportunities might have been an additional motivation for joining the different missions of the ARC in Europe, it is not entirely clear why older and established people would leave their homes to subject themselves to hardships and suffering. There are several reasons to consider. First of all, a strong sense of patriotic duty must have influenced their decisions. Although service in the ARC was not a substitute for combat, the militarization of the ARC after 1917 was viewed as an alternative form of service by many men who were beyond draft age. Businessmen, doctors, and professors, including Edward Capps, became majors and lieutenant colonels overnight (Irwin 2013, pp. 119-121).

One also has to acknowledge the cosmopolitan nature of American society during the Progressive Era, a prospective that encouraged international activities. But most of all, by being part of the ARC in the first two decades of the 20th century, one belonged to a new professional elite, “drawn from the ranks of the U.S. government and corporate America” (Irwin 2013, p. 7). These men and women were similarly minded and well-educated people who had embraced the scientific management theory for economic efficiency and labor productivity.

The new elite, proud to manage philanthropic foundations and organizations such as the ARC, also shared President Wilson’s larger vision for global peace and international order. In addition to substituting “dollars for bullets,” America had found another way to reach out to the world by offering a new type of civilian aid: non-sectarian, preventive, and constructive. By trusting its humanitarian mission to an army of professionals, the ARC conferred “a greater sense of cultural prestige” to the international work of the organization (Irwin 2013, p. 36).

The ARC Greek Commission at Work

With the preceding discussion as a background, I now come to the main part of my post: that is, the work of the ARC in the Aegean. The members of the Greek Commission arrived in Greece, via Paris, on October 23rd, 1918. Upon their arrival in Athens, Commissioner Capps and his deputies were taken to the ASCSA, which had been rented by the ARC to be used by the deputy commissioners as sleeping quarters. The rest of the commission boarded in Athenian hotels. For its headquarters, the Commission rented a large private mansion at 19, Kephissias Street.

By December the Commission had already dispatched three missions: one to Eastern Macedonia to facilitate the repatriation of more than a hundred thousand Greeks who had been taken as hostages to Bulgaria during the war; a second to Southern Epirus to investigate reports of extreme starvation, and a third to Mytilene and the adjoining islands to offer civilian relief to Greek refugees from Asia Minor. (For the ARC mission to the Eastern Macedonia, Davis 2013; and Hatzivassiliou, 2014.)

ARC Deputy Commissioner A. Winsor Weld. ASCSA Archives, Carl W. Blegen Papers.

I have consulted three types of sources for the mission to the islands: a) ARC’s published reports; b) professional correspondence and unpublished reports in the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington D.C.; and c) personal papers of members of the Greek Commission housed in various U.S. libraries and archives. In one case, I was fortunate to locate and buy from an antiquarian bookseller a rare privately circulated volume reproducing letters that A. Winsor Weld, one of the deputy commissioners, sent to his family from Greece in 1918-1919 (Aegean islands: Dec. 10-24 and Febr. 15-25). Weld, an investment broker from Boston, was placed in charge of civilian relief in the Aegean, and is also the author of a long report about the activities of his mission. (For Weld’s first impressions of Athens and Greece, read “Athens 1918: “In Every Way a Much More Attractive City than Rome.”)

The Aegean Expedition

On November 6, 1918, Weld dispatched to Mytilene an expedition accompanied by a shipload of supplies to provide civilian relief to thousands of refugees from Asia Minor. Dewing, the Secretary of the Commission, headed the mission; he was no stranger in the Aegean. From 1910 until 1916 he had served as dean of Robert College in Istanbul. Capps must have included Dewing in his party for his familiarity with the region and the language. The problem of language communication is not mentioned in the official reports but appears frequently in Weld’s letters to his family. Once outside Athens the members of the Commission could hardly find any Greek who could speak more than a few words of French. Dewing would do most of the talking when members of the Commission conducted business with Greek officials in the islands (Weld, Letters, p. 94).

Using Mytilene as a base, relief was also distributed to the islands of Tenedos, Imbros, and Samothrace, as well as to the city of Aivali in Asia Minor. Two more stations were established on Chios and Samos. Each station maintained a residence for personnel, a warehouse for supplies, and suitable quarters for its various activities (Weld, “Relief Work”, p. 4). In the official and unofficial reports it is repeatedly mentioned that transportation of supplies and people from Piraeus to the islands but also from one island to the other was “exceedingly difficult.” To facilitate island communication in January 1919, the U.S. navy placed at the disposal of the Greek Commission six submarine chasers (Weld, Letters, p. 117).

The Greek Commission heading to Chios with one of the U.S. submarine chasers.

A Wretched Situation

The Commission found the refugees underfed and clad in rags. “Very few children have shoes and stockings,” Weld described in his report (Relief Work, p. 9). The soup kitchens that the Greek state ran in Mytilene allowed for one dish of soup or vegetable each day and such kitchens did not exist outside the town (Weld, Relief Work, p. 18). In addition, a large epidemic of influenza had stripped the hospitals of medicines. The refugees lived like squatters in abandoned and half-destroyed Turkish houses, in deplorable sanitary conditions. In the towns, because of lack of space, families of 8-10 people were forced to live in one room. On the island of Mytilene alone, the Greek Commission reported “a refugee population of 52,000 quartered on a native population of 180,000)” (Weld, Relief Work, p. 19). How wretched the situation was on the islands is best described by Weld who, while attending a funeral, was shocked to see that “the beautiful burying clothes and everything is taken off before the body is covered, clothing too valuable to lose” (Weld, Letters, p. 105).

The ARC organized its civilian relief on these islands along three lines: a) it opened workshops for making clothes (ouvroirs); b) it distributed food and clothes; and c) medicines were dispensed by trained nurses. Since the Greek authorities had established Refugee Bureaus, distribution of relief was done in an organized and fair manner.

Putting Refugees to Work

Opening workshops to make clothes was an intelligent way to occupy women refugees, and to teach them a skill; by earning some income to support their families these women avoided prostitution. On the island of Samos, the workshop occupied 65 women, who worked from 8.30 to 5.30 and produced from 200 to 300 garments daily. The nurse supervising the Samos workshop reported that “no work was too great for them, and each was paid according to the number of garments made and the quality of her work. The rivalry kept a sharp edge on the results” reported nurse Ethel G. Hazlewood (Weld, Relief Work, p. 40).

Paid work was part of the ARC’s overall philosophy, which did not focus only on temporary relief, but strongly emphasized creating foundations for “orderly, industrious postwar societies,” where people remained productive and self-supporting, and children were well-fed and educated (Irwin 2013, p. 71). Clothing was distributed in small parcels. Getting these parcels to the population that lived outside the large towns on the islands was a real trial for the members of the Commission. Travelling by donkeys and mules, sometimes it would take a full day to reach an isolated village.

“Chios. Investigation party on the Chios Rapid Transit” (written on the back of the photo). Horace S. Oakley Papers, Newberry Library.

The ARC had a tradition of distributing farm equipment and seeds to encourage agricultural work. In fact, when the Greek Commission was being formed, the Greek government asked “if we should include in our mission an expert in soil fertility,” Capps wrote in his report (Capps 1919, p. 27). It is no surprise, therefore, that one of the seven deputy commissioners, Cyril Hopkins (1866-1919), a professor of agronomy at the University of Illinois, came to Greece to study the soil and suggest ways of improving its efficiency. His report was the only one of the Greek Commission’s reports that was published in Greek. His report also explains the mystery of the capital Greek letters appearing on the photos of the Greek Commission. What originally looked like fraternity letters but did not make any sense in the context of an ARC photo were, in fact, the symbols for chemical elements. During his time in Greece, Hopkins had collected and analyzed hundreds of samples of soil, in an effort to make Greek soil more productive. Unfortunately, Hopkins died of malaria at Gibraltar in October 1919 on his way back to America.

Hopkins believed that the addition of phosphorus (Φ) and other fertilizers to the Greek soils would double the size of the crops. He also used his fellow commissioners (e.g., see the photo of Capps above) as scale in his photos, to show the different results of his experiments. ASCSA, Gennadius Library.

Food Distribution

Aiming at better nourishment for the starving refugees, the Commission added rations of beans twice a week. As a complement to the rice that the Greek government had sent, the ARC added milk and sugar to transform it into a nutritious ρυζόγαλο. Finally, the ARC supplied the kitchens with flour in order to add macaroni to their sparse menu (Weld, Relief Work, p. 28). The Commission also made sure that supplies of food and clothing were distributed to the orphanages.

Distribution warehouse. Source: Horace S. Oakley Papers, Newberry Library.

Weld makes another important point in his report. The distribution of the supplies was done directly by members of the Commission, “in order that our help should not be merely of the physical kind but should also bring into it something of a personal element and thereby help to cement a friendly feeling and to show that the American people were directly interested in their lives and comfort” (p. 15). Chester H. Aldrich, an American architect and head of the Italian Commission, had blatantly reminded his delegates that all relief needed to possess “an American character pronounced enough to constantly remind everyone connected with it that this help comes from America” (Irwin, p. 119, and n. 48).

By creating an environment of lasting appreciation of the United States, knowingly or unknowingly, the ARC workers of the Greek Commission (and the other Commissions) were spreading the seeds for Wilson’s peacetime visions of a safe and well-ordered world, evoking his famous Fourteen Point speech of January 1918 (Irwin 2013, p. 125). Dewing in his report exalted the friendly reception of his team by the habitants of Mytilene. “The streets resounded, during the progress through the city, with cheers for the American people and for President Wilson. The name and fame of Wilson is familiar in every household on the Island of Mytilene as, indeed, it is through the length and breadth of Greece” (Weld, Relief Work, p. 17).

The issue of U.S. propaganda surfaces also in Weld’s report: first, the ARC workers were initially suspected by locals of being agents of political propaganda by the local inhabitants but, when they went about their business not favoring any parties, that idea soon ended. Then they were suspected of religious propaganda but “the number of priests who came to watch our work, and frequently to share in its benefits, proved that was wrong” (Weld, Relief Work, p. 36).

Teaching Preventive Care

While the European Red Cross societies limited their aid to the battlefield, the American Red Cross from the beginning embraced a broader mission by investing heavily in preventive, long-term care. As soon as America entered the war in 1917, the ARC, with financial support from the Rockefeller Foundation, undertook a large anti-tuberculosis campaign in France to fight the resurgence of tuberculosis during the Great War. The French campaign initiated a series of other public health initiatives which included educating women in the principles of public health and nursing (Irwin 2013, pp. 129-130). The Greek Commission included two experienced doctors from Chicago: surgeon Carl E. Black (1862-1944) and physician Samuel Walker. After surveying 47 military and 49 civilian hospitals Black produced a report about their needs and, accordingly, the ARC distributed aid (Black 1919).

In the papers of deputy commissioner Horace S. Oakley (Newberry Library, Chicago) I found a snapshot taken at the ARC dispensary on the island of Chios. The head nurse is demonstrating to expectant mothers how to bathe and clothe babies properly. At the end of each of these demonstrations the future mothers would receive a layette containing a blanket, soap, and clothes for the infant. Weld recorded in one of his letters that the layettes were so eagerly sought after by the refugees that it led to “attempts to obtain them by false pretenses, through the use of padding to give the necessary appearance” (Weld, Letters, p. 90).

“Chios. Miss Johnson giving layette demonstration to 30 expectant mothers” (written on the back). Horace S. Oakley Papers, Newberry Library.

The Aftermath

With the repatriation of the Greeks from Bulgaria and the return of the refugees to Asia Minor, the Greek Commission concluded its relief work in May 1919. Capps and some of the deputy commissioners, including Weld, stayed throughout the summer to write their reports.

Presenting final reports to the ARC administration in Washington was part of the organization’s concept of scientific management. In addition to describing past activities, the reports also included plans for constructive work of more permanent character. Capps was pursuing appropriations from the ARC to support a training school for nurses, child welfare stations, and orphanages for a period of five years. Instead, Greece received funding for one year only.

Financial reversals had forced the ARC to suspend most of its European long-term programs by June 1st, 1920. The American people not only had limited their contributions to the ARC, but they were also expressing serious concerns about its plans for international expansion during peacetime. Wilsonian internationalism and the public support for the ARC, once kindred spirits, waned completely after Wilson retired from the U.S. presidency in 1921. From now on the ARC would only respond to emergency calls.

When in the early fall of 1922 Greece placed another emergency call to the ARC, there was a robust American community already in Athens to take immediate action. The Athens American Relief Committee included Harry Hill, the manager of the American Express Company, and W.S. Taylor, the representative of Standard Oil. The person who organized the actions of this temporary committee was none other than Bert Hodge Hill, the director of the American School. And it was Edward Capps to whom Eleftherios Venizelos wrote in January 1923 asking for his support in the organization of refugee settlements after the departure of the ARC. From 1923 to 1928 Bert Hodge Hill would take time off from his director’s duties (which ended in 1926) to work diligently for the Refugee Settlement Commission, personally inspecting refugee settlements in all parts of Greece, including the Aegean islands (Daleziou 2013, pp. 54-57).

The School through its involvement with ARC would also gain the life-long support of deputy commissioners Weld and Oakley. Both served on the Board of Trustees of the School. Weld would also become the Treasurer of the Board from 1946 until his death in 1956. Both followed the School’s affairs with great interest. In the Newberry Library at Chicago where the Oakley papers have been deposited, there is extensive correspondence between Oakley and Capps about the progress of the School’s negotiations with the Greek government concerning the concession of the Athenian Agora excavations. Furthermore, in 1926-1927, Oakley donated $5,000 to the School for the erection of an excavation house at Corinth (the so-called “Oakley House”). Oakley’s sudden death in 1929 deprived the School of a committed friend.

ARC Deputy Commissioner Horace Oakley. Newberry Library.

The Oakley House at Corinth. ASCSA, Corinth Excavations.

Primary Sources

NACP = National Archives at College Park, College Park, Md.

Newberry Library (Chicago), Horace S. Oakley Papers

Weld, Letters = A. Winsor Weld, Letters from Greece, 1918-1919 (privately published).

Publications

–Carl E. Black, Survey of the Hospitals in Greece (Athens 1919).

–Edward Capps, The American Red Cross in Greece (Athens 1919).

–Louis P. Cassimatis, American Influence in Greece, 1917-1929 (Kent 1988).

–Eleftheria Daleziou, “ ‘Adjuster and Negotiator’: Bert Hodge Hill and the Greek Refugee Crisis, 1918-1928”, in J. L. Davis and N. Vogeikoff-Brogan (eds.), Philhellenism, Philanthropy or Political Convenience? American Archaeology in Greece, Hesperia (Special Issue) 82:1 (2013), pp. 49-65.

–Jack L. Davis, “The American School of Classical Studies and the Politics of Volunteerism”, in Jack L. Davis and Natalia Vogeikoff-Brogan (eds.), Philhellenism, Philanthropy or Political Convenience? American Archaeology in Greece, Hesperia (Special Issue) 82:1 (2013), pp. 15-48.

–Dimitra Giannuli, “American Philanthropy in Action: The American Red Cross in Greece, 1918-1923,” East European Politics and Societies 10 (1995), pp. 108-132.

–Evanthis Hatzivassiliou, Βιώματα του Μακεδονικού Ζητήματος. Δοξάτο Δράμας, 1912-1946 (Athens 2014).

–Cyril G. Hopkins, Πώς η Ελλάς μπορεί να παράγη περισσότερη τροφή (Athens1919).

–Julia F. Irwin, Making the World Safe: The American Red Cross and a Nation’s Humanitarian Awakening (Oxford 2013).

–A. Winsor Weld, Relief Work among the Aegean Islands (Athens 1919).

Thank you, Natalia, for another interesting chapter of ASCSA history. It always amazes me to learn of all the things that have gone on beyond the regular activities of the School. I hope somebody is keeping a record of the School’s current unofficial support of refugees now, because it will some day be an important part of our history.

Maria, thank you for your nice comments. Some of the School’s recent support to the refugees can be retrieved through Facebook. The next historian of the School will have to include Facebook and Twitter in his/her research.

[…] We’re professors and we’re here to help. […]

[…] We’re professors and we’re here to help. […]