The Transatlantic Voyage of a Greek Maiden

Posted: April 17, 2021 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Classics, History of Archaeology, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism, Women's Studies | Tags: Acropolis Kore 675, Gisela M. Richter, Greek Pavilion World Fair 1939, Henry Morgenthau, Hermes of Praxiteles, Spyridon Marinatos 7 CommentsOn March 31, 1947, Gisela Richter, Curator of Greek and Roman Art at the Metropolitan Museum of New York, sent a confidential letter to Carl W. Blegen, Professor of Classics at the University of Cincinnati and a distinguished archaeologist. Richter approached Blegen not only because they were friends but because, by having lived in Greece for many years, Blegen had formed strong connections with the local community at all levels. In addition, during World War II, Blegen had offered his services to the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and, upon his return to Greece, he had served as Cultural Attaché at the U.S. Embassy (1945-1946). Richter was writing Blegen about five pieces of Greek sculpture on loan to the Metropolitan Museum, including Kore 675 from the Acropolis. Richter refers to her as the “Maiden”.

“As I think I told you, we are naturally anxious to return to the Greeks what they have kindly lent us but very much hope that some arrangement can be made by which we may retain that one Maiden. The other pieces we are not even going to ask for, as there are obvious reasons in each case why the Greeks would not want to part with them, and asking for them would only weaken our case for the Maiden. The latter is one of many, and would hardly be missed in Athens, whereas here she would act as an ambassadress of goodwill, etc., etc.”

Richter sought Blegen’s advice about how to proceed with the request. “The loan to Greece ought to create goodwill for America, but naturally we don’t want to seem to cash in on it.” Richter was referring to President Truman’s announcement of March 1947, known as the Truman Doctrine, whereby the U.S. government granted $300 million in military and economic aid to Greece and $100 million to Turkey. “Would it be better to ask for the piece as a gift and perhaps compensate for it in some other way, or would a direct purchase be better? You who have been in Greece recently and know Greek politics will be able to advise us better than anyone else,” concluded Richter.

Blegen’s response exists only as a draft in his personal papers at the Archives of the American School of Classical Studies (ASCSA or School hereafter). The mention of [Spyros] Skouras’s name in his response (not mentioned in Richter’s letter) suggests that Richter might have followed up with a second letter or a telegram or a note to Blegen’s wife, Elizabeth. To Richter’s disappointment, Blegen could not think “of any altogether satisfactory way of approach to recommend” (ASCSA Archives, Carl W. Blegen Papers, Box 13, folder 1, April 6, 1947). However, he did not reject the idea of having Spyros Skouras, the Greek-American movie mogul, mediate with the Greek authorities “since he has much influence and could apply some pressure. If he could propose it in the right quarters as an idea of his own, not inspired by you, there might be some hope that he could persuade them to make the offer as a spontaneous gesture of friendship.” Blegen thought of another alternative as well: “to ask Bert [Hodge] Hill to try his powers of persuasion.” Hill, Director of the American School from 1906 until 1926, was still considered to be social capital by many at the School. A gifted individual with access to the upper echelons of a small Athenian society, including the royal family, Hill “had his way with men” and could influence politicians. Blegen thought that it would have to be a political decision since the Archaeological Service would likely oppose to it.

There is no other correspondence between Blegen and Richter on this matter. We know that the Acropolis Maiden and the other pieces of sculpture were returned to Greece, so one assumes that either Richter did not press the issue further or that the mediators were unsuccessful. However, it is interesting to read an announcement in the Greek newspaper ΕΛΕΥΘΕΡΙΑ on August 11, 1948, titled “The Greek State will Sell Certain Antiquities. Superfluous in Museums,” which implies that the Ministry of Education might have considered briefly the idea of selling duplicate antiquities, in order to finance the reopening of Greek museums and the beautification of those archaeological sites that had suffered much during the War.

Eight Years Earlier

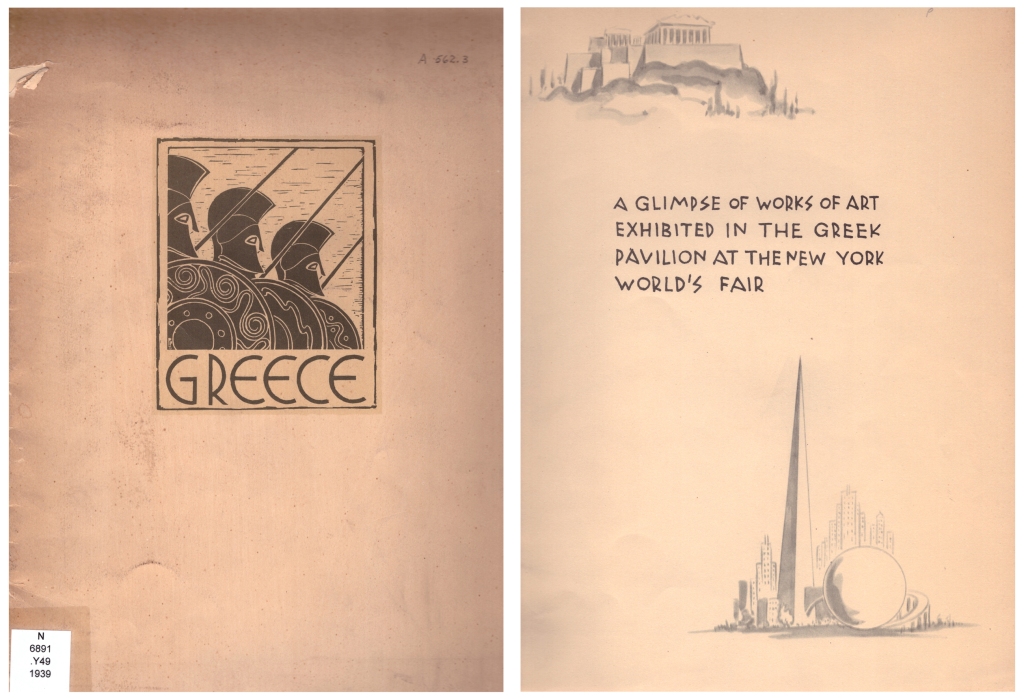

With these two letters in hand, I began to work my way backward in order to find out why and when these five sculptures had been lent to the Metropolitan Museum. A search in the annual reports of the curators in the Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum Art (BMMA) proved rewarding. In the BMMA of 1939, Richter contributed a section titled “A Loan of Greek Sculptures from Athens” (pp. 239-240). In it, we learn that the five originals had been sent for the Greek Pavilion on the occasion of the World’s Fair in New York and, while in New York, they were also on display in the Met’s galleries. The loan had been negotiated with Spyridon Marinatos (1901-1974), General Director of Antiquities in Greece, and Nicholas L. Lely, the Greek Consul General in New York. Richter proudly reported that “they are the first loans from Greece to cross the Atlantic –in fact, never before has Greece lent a single example of the great treasures in her museums to any country.”

And which were the five pieces that the Greek Government had sent to the World Fair? The Maiden from the Acropolis Museum (no. 675), a work of the late 6th century B.C. that had been discovered in the excavations on the Acropolis in the late 19th century; the gravestone of Ampharette, a work of the late 5th century B.C., found in the Kerameikos; the head of “Ariadne” of the 4th century B.C., found in the Athenian Asklepieion; a little bronze head from Perinthos in Thrace that the National Museum had recently acquired (1935); and finally, the marble head of a Titan by the famous sculptor Damophon, which had been discovered in the Sanctuary of Artemis Lycosoura in Arcadia in 1889.

Richter described the little Maiden as: “a dainty, charming lady, with an elaborate coiffure, rich garments, and a radiant smile. The comparatively well-preserved colors (red on hair, lips, mantle, ornaments; blue –now oxidized to green –on tunic, diadem, earring; purple on borders; and so forth)… They enable us to appreciate how successfully the Greeks used color on sculpture.”

The Fiasco of Another Loan

Richter was right to emphasize in her report the Metropolitan Museum’s success in arranging the first-ever display of Greek antiquities outside Greece. Until then, Greece had participated in world fairs with casts only. Many Americans of Richter’s generation would have remembered the fiasco of another loan in 1924. In that case, the request had not come from an American museum but from a private individual, Henry Morgenthau (1856-1946).

In 1923, Morgenthau, former U.S. ambassador to the Ottoman Empire (1913-1916) as well as a successful businessman, had been appointed by the League of Nations to head the Refugee Settlement Committee in Greece following the Asia Minor Catastrophe of 1922. More than that, Morgenthau had publicly condemned the Turks for having committed atrocities against the Armenians, the Greeks, and other minorities of the Ottoman Empire. To honor Morgenthau’s philhellenism and philanthropic work, the Greek State decorated him with the Grand Cordon of the Savior.

According to The New York Times, before leaving for the U.S., Morgenthau approached the Greek Government with “a proposal that he take the statue by Praxiteles of Hermes… on a tour of the United States for the purpose of raising $12,000,000 in behalf of Greece’s refugees. Mr. Morgenthau said that he was convinced that New York City alone would give $1,000,000 to see the statue. The Vima [a Greek newspaper] said that Greece might consent to the proposal if the request came from the American government and a warship was sent to fetch it” (April 24, 1924). A few days later the same newspaper reported that “it is thought a special case could be built for a national tour, and [that] Mr. Morgenthau believed popular subscriptions from universities, art museums and municipalities would amply cover the cost of the transportation of the statue” (The New York Times, April 28, 1924).

Other newspapers, such The Guardian, presented the story slightly differently, attributing the initiative for the loan to the Greek Government: “These are great times for ‘gestures’… But for the moment the Greek Government beats the record in gracefulness of international gesture by offering America a free loan of the most precious of all Greece’s portable treasures of art… Facing all the perils of shipwreck and land accident, the Greeks offer to let Americans, in all their great cities, have a sight of this world’s wonder with their own eyes, in return for American generosity to Greek sufferers by the war…”(May 3, 1924). The Boston Globe mockingly worried that: “After a few weeks’ travel on American railroads he [Hermes] will look like a statue of Humpty Dumpty after the fall” (May 6, 1924).

At any rate, the proposal met strong objections from the international archaeological community. Edward Robinson, the Director of the Metropolitan Museum, was quoted saying that “while he sympathized with the sentimental side of the proposal, the technical problems involved in the transportation of the statue are so serious that there would be danger of the loss of the Hermes to the world. Other lovers of art in this country are gasping at such a possibility and powerful opposition has developed against…” (The Indianapolis News, May 24, 1924). Moreover, the Managing Committee of the ASCSA in its May meeting passed a resolution that [the School] “is emphatically opposed to the proposal to bring the Hermes of Praxiteles to the United States for exhibition, because of the risk of damage that would attend its removal.”

In addition, in the records of the U.S. Embassy in Athens, there is another resolution signed by thirteen directors of U.S. art museums for the American Association of Art Museum Directors: “… the people of the United States should not become a party to any transaction that might result in irreparable injury to this priceless heritage of Greece (NARA 868.4032, May 8, 1924). A month later Ray Atherton, ad interim United States Ambassador to Greece wrote to Charles Evans Hughes, Secretary of State: “I believe that the proposal was not seriously made by its American originator [meaning Morgenthau], though even the suggestion of such action evoked a storm of protest locally” and that the Greek Minister of Foreign Affairs had assured Atherton that permission would never be given (NARA 868.4032/2, June 7, 1924).

The Greek Pavilion at the World Fair of 1939

Fifteen years after the Hermes fiasco, the Greek government, under Prime Minister Ioannis Metaxas, and the archaeological community agreed to send the five pieces of ancient sculpture to New York for the World’s Fair. Soon after his appointment as Prime Minister in 1936, Metaxas proceeded to establish an authoritarian and nationalist regime that lasted until his death in 1941. Even if there were any objections, they were not made public.

Niki Sakka and Yannis Hamilakis in separate works have discussed extensively the ideology of Metaxas’s regime in relationship to antiquity, such as the promotion of Spartan ideals and the glorification of the military campaigns of Alexander the Great, as well as the close ties between Hellenism and Orthodoxy. With the enthusiastic support of Spyridon Marinatos, Director of Antiquities since 1937, Metaxas’s regime saw the World’s Fair of 1939 as an opportunity to showcase internationally the glorious past of Greece, as well as select features of modern Greece. There was an emphasis on peasant life and folk art, with titles such as: “In this Classical land of Greece peasant life goes on as of old.”

The Gennadius Library has a copy of the exhibition catalogue which also featured full-page portraits of King George II, Prime Minister Metaxas, and Press Secretary Theologos Nikoloudis, all by Elli Sougioultzoglou-Seraidari (Nelly’s), the renowned Greek photographer and a favorite of the Metaxas’s regime.

For the construction of the Greek pavilion in New York, designed by architects Dimitri and Alexandra Moretis, it is said that 60 tons of marble were quarried in Greece and sent to the States. (After the dismantling of the pavilion, the marble was shipped to Tarpon Springs in Florida for the construction of St. Nicholas church.) A plaster cast of the statue of Hermes by Praxiteles was placed outside the pavilion. Four big murals by artist Gerasimos Steris (an artist who often changes names, nationalities, and countries) illustrating the history and continuity of Greek civilization decorated the façade of the pavilion. The interior was dominated by large photographic collages by Nelly’s which juxtaposed ancient portraits with portraits of contemporary Greeks so as to show the racial continuity of the Greek nation. The five pieces of sculpture together with plaster casts of other well-known Greek statues were on display there. (I have not been able to locate good quality photos of the exterior or the interior of the Greek Pavilion on the web.)

The World’s Fair opened on April 30, 1939, at Flushing Meadows–Corona Park in Queens. On the occasion, the Greek Consul in New York invited Marinatos for a grand lecture tour to present the results of his excavations on Crete, Cephallonia, and his latest at Thermopylae. The latter had already been covered extensively in the press with titles such as: “Seeks Tombs of Ancient Spartans” and “Tombs of Ancient Spartan Heroes are Being Sought at Thermopylae (The Baltimore Sun, July 9, 1939; Winnipeg Tribune, July 18, 1939).

Marinatos was also meant to supervise the return of the five originals. However, Hitler’s invasion of Poland in September 1939 and the subsequent declaration of war against Germany by England and France made a safe passage for the Greek antiquities a risky business. The Greek Government in consultation with Marinatos made the decision to lend the five sculptures to the Metropolitan Museum for the duration of the war (ASCSA Archives, Spyridon Marinatos Papers, Box 2, folder 5) “The collection, valued at $2,000,000, is too valuable to entrust to ocean travel and the menace of submarine attack,” wrote The Evening Sun on October 19, 1939.

And thus the visit of the Acropolis Maiden to America was extended from a few months to eight years.

Epilogue

In 1963, in anticipation of the 1964 New York World’s Fair, the Greek Archaeological Council rejected once again a proposal to send the Hermes statue on a transatlantic voyage. In fact, the Council “opposed in principle the removal of any ancient art treasures from Greek territory” (The New York Times, November 18, 1963). John Kondis, the Director General of Greek Antiquities was quoted saying: “many dangers are involved. We’re definitely opposed to the export of any antiquity.” In addition, Kondis “recalled that in 1938 three statues were sent to the New York Fair against the council’s advice” and that “they were overtaken by war there and were repatriated 10 years later.”

But by the 1960s, Greece could participate in the World’s Fair with another kind of cultural commodities. For example, on May 24, 1965, a special screening of the movie Zorba the Greek was organized at the Greek Pavilion. The movie had already won three Academy Awards and was scheduled to open at eleven theaters in New York the following day (The Morning Call, p. 10). Other newspapers reported that Greece was advertising its cuisine: “A famous Greek chef is in charge of the food preparations. Featured will be a cheese pie called Tiropitta, also the Moussaka casserole made of ground-beef, eggplant and cheese” (The Spokesman Review, March 22, 1964). However, the Daily News published a letter/complaint by the Consul General of Greece, titled “Greece in the Clear,” informing the public that “this pavilion and restaurant is not under the sponsorship of the Greek Government. As is the case with many other countries and their exhibits, this pavilion was erected and sponsored by various Greek businessmen who have no affiliation whatsoever with the Greek government” (September 30, 1964).

FURTHER READING

Hamilakis, Y. 2007. The Nation and its Ruins: Antiquity, Archaeology, and National Imagination in Greece, Oxford.

Mantzourani E. and N. Marinatou (eds.), 2014 . Σπυρίδων Μαρινάτος, 1901-1974. Η ζωή και η εποχή του, Athens.

Markessinis, A. 2016. The Greek Pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, Torrazza Piemonte.

Richter, G. 1972. My Memoirs: Recollections of an Archaeologist’s Life, Rome.

Sakka, N. 2002. Αρχαιολογικές δραστηριότητες στην Ελλάδα (1928-1940): Πολιτικές και ιδεολογικές διαστάσεις (Diss. University of Rethymnon).

Fascinating. Thanks again, Natalia.

Intriguing story, Natalia. Good detective work. You may have missed your true calling. Always a good read. Thanks. Glenn

Thanks, Glenn. It’s about contextualizing…

Thanks for this Nataliya — doubly interesting because of the NYC connection for me (my mom had stories about the 1964 World’s Fair), and now triply because I have a Master’s student working on Greece’s cultural heritage laws. I will share this with him!

Thanks, Susan! That’s a very good topic (i.e. the MA thesis).

[…] Vogeikoff-Brogan, N. “The Transatlantic Voyage of a Greek Maiden,” From the Archivist’s Notebook Blog, April 17, 2021. […]

[…] Vogeikoff-Brogan, Natalia. 2021. “The Transatlantic Voyage of a Greek Maiden,” From the Archivist’s Notebook Blog, April 17, 2021. […]