Recalling a Museum Theft

Posted: April 21, 2022 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Art History, Classics, History of Archaeology, Mediterranean Studies, Philhellenism | Tags: Athenian Agora Excavations, Charles H. Morgan, Christine Alexander, Eugene Vanderpool, Homer A. Thompson, Γιάννης Μηλιάδης, John L. Caskey, John Meliades 4 Comments“Sadly, the best candidate for him, the beautifully carved [head] 3, facing right, was stolen from the Agora’s dig house in 1955, while the Stoa of Attalos was under construction.” This sentence caught my attention while reading “Classical Sculpture from the Athenian Agora, Part 2: The Friezes of the Temple of Ares (Temple of Athena Pallenis),” published in Hesperia 88 (2019) by Andrew Stewart and seven co-authors (E. Driscoll, S. Estrin, N. J. Gleason, E. Lawrence, R. Levitan, S. Lloyd-Knauf, and K. Turbeville). Further below in the catalog entry for the head, the exact date of the theft is also mentioned: August 22, 1955.

Stewart et al. refer to a fragmentary male head of high craftsmanship that was found in the Athenian Agora near the northeast corner of the Temple of Ares in 1933. Carved around 430-425 B.C. and identified as Hermes, the small head (H.: 0.147m) is one of forty-nine half-size marble fragments which once decorated the friezes of the Temple of Ares in the Agora (originally the Temple of Athena Pallenis at Pallene). A plan of the Agora with the findspots of the sculptures is included in the Hesperia article, and is also available at https://ascsa.net.

Thefts occur in even the best guarded museums and libraries. Every institution has its own story (or stories) to share or hide. And at least some thefts are committed by those who have “hands-on” access to the collections. A recent example was the return of two valuable journals of Charles Darwin, which were stolen two decades ago from the library of Cambridge University. Others remain lost–the paintings stolen from the Isabella Gardner Museum in Boston in 1990, or the Telephus head, an original by Skopas, removed from the Tegea Museum in 1992.

But back to the little head of Hermes that was inventoried as S 305. I was curious to discover more about its theft. A search in the Archives of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or the School hereafter) yielded considerable information about the event and its aftermath.

On September 6, 1955, the School’s Director, John L. Caskey, found himself in the unpleasant position of reporting to the Chair of the Managing Committee, Charles H. Morgan, that “one of the fine small marble heads from the Altar of Ares in the Agora was stolen recently. You will remember that a series of these heads was on a window sill in the inner courtyard. The head was twisted out of its plaster base. The loss was reported to the Ephor, the Symvoulion discussed it (not unsympathetically, according to George Mylonas), the police were notified, and small notices appeared in the papers. Modiano, who is very alert, picked it up immediately and put a bit in the Times of London. I wonder whether the story reached America. There’s nothing more we can do except, as Homer [Thompson] says, hurry up and move to the Stoa” (AdmRec Box 318/5, folder 8). [The photo on the left and its title are reproduced from Stewart et al. 2019.]

There was a delay of about two weeks between the theft (August 22) and Caskey’s report to Morgan because the School’s Director was not informed immediately. Apparently the staff members of the Agora were slow to convey the news either to the School’s Director or to the Ephor of the Acropolis, John Meliades. Eugene Vanderpool, who was in charge of the Agora Excavations when its Director Homer Thompson was in America, wrote to Thompson on August 29 (seven days after the theft). “Meliades came down this morning and I told him all the details. He was sympathetic and helpful. Later in the morning I took him a written account of the affair drawn up by Kyriakides [Aristeides Kyriakides was the School’s lawyer]… [and] I enclosed several pictures” (Homer A. Thompson Papers, box 68, folder 4).

Since the head had never been published, Meliades urged Vanderpool “to publish it as soon as possible so as to make public the claim to it.” The next day Vanderpool supplied journalist Makis Lekkas of Vima (BHMA) and Nea (NEA) with a short text and a photo which gave the appearance that the Hermes’ head had just been found during cleaning operations in the area of the Temple of Ares. Vanderpool further suggested to Thompson that the theft should be included in the School’s Annual Report, “so that it will become known in the scholarly world. Then if an attempt is made to sell it to a museum it can be identified. Meliades tells me that if a foreign museum buys it, the Greek Gov[ernmen]t can reclaim it as stolen property under existing international agreements.” As planned, on August 31, a short piece appeared at NEA, titled “Σημαντικά ευρήματα εις την Αρχαίαν Αγοράν” (Important finds at the Ancient Agora).

Meliades immediately reported the theft to the Archaeological Council. An off-the-record note by Mylonas, who was present at the Council’s meeting, suggested that members were understanding and “that while it was too bad, such things do happen occasionally.” The Minister of Education, who presided over the Council, personally telephoned the police and reported the theft (Homer A. Thompson Papers, box 68, folder 4, Vanderpool to Thompson, Sept. 1, 1955).

The Cat’s Out of the Bag

Just as he was about to mail his letter, Vanderpool rushed to add a last-minute postscript: “It looks as though the cat were out of the bag. Today’s NEA reports the theft, having gotten it from police bulletin. Modiano [the Greek correspondent in London] called up at 12.10 for more details… and it will be in London Times.” On September 2, the London Times published a note together with a photo of the stolen head: “500 B.C. Bust Stolen from Museum.” By then the Director of the School must have also found out about the theft although there is no mention of Caskey in the dispatches that Vanderpool sent to Thompson or in all their dealings with the Archaeological service.

After that initial interest, the press dropped the matter quickly, but not the Archaeological Service. On September 9, Spyridon Marinatos, Director of Antiquities, Christos Karouzos, Director of the National Archaeological Museum, and Ephor John Meliades visited the “scene of the crime” and met with Vanderpool. Three days later Caskey received an official reprimand signed by the Minister of Education, Achilleas Gerokostopoulos. In it, the School was accused of having inexcusably delayed, almost by a week, in informing the Service of the theft. As a result, the police had lost valuable time. The School was also reproached for not storing such a prime piece of sculpture in a safer location; instead it was in an exposed and unsecure location. Finally, by not publishing it for twenty-two years, the School had made repatriation more difficult in case it had already been smuggled outside Greece (Homer A. Thompson Papers, box 111 folder 1, enclosed in a letter from Caskey to Thompson, Sept. 16, 1955).

“The School gets a black eye out of this, which could have been avoided if we had reported the loss to Meliades at once. In the future I’d like to hear from the Agora staff immediately whenever anything happens that may affect our standing or relations with the officials and the local public,” Caskey rebuked Thompson. The rest of Caskey’s letter referred to the animosities between Greece and Turkey “over the Cyprus business,” and the progress that had been made concerning the reconstruction of the Stoa of Attalos: “The fluting of the eight columns is a fine sight.”

Morgan writing to Vanderpool from the other side of the Atlantic was more sympathetic about the theft. “It is a pity it has gone. I remember it well and believed it to be by one of the sculptors of the Parthenon frieze. Unfortunately this is the kind of thing that happens in the best of regulated museums, one of these things that no number of special guards or protective devices can entirely obviate… such as Princeton three years ago with three Rembrandt prints stolen during a commencement exhibition” (AdmRec 318/5 folder 8, September 13, 1955).

There is one last mention of the stolen head in the School’s records. On September 24, 1955, Vanderpool writing again to Thompson referred to some fake news about the missing head: “A clue which led to the Elsa Maxwell cruise proved false. Someone on the cruise had indeed bought a small head but it was not ours. It is a long and rather amusing story. Dick [Richard Hubbard] Howland knows it and would be glad to tell it if he sees you. I may write it someday.” Vanderpool also added that the Agora staff had “closed the courtyard to the general public: too bad, but really much better so” (Homer A. Thompson Papers, box 68, folder 4).

Maxwell (1883-1963) was a famous gossip columnist who was known for entertaining high-society guests at her parties and being friends with celebrities such as the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, Aristotle Onassis and Maria Callas. In late August 1955 Maxwell together with actress Olivia de Havilland organized a 15-day cruise in the Aegean for 113 members of European royalty and other high-society types, aboard the luxury yacht Achilleus, lent by the Greek shipping magnate, Stavros Niarchos. Although Maxwell’s cruise was not connected to the theft, cruise boats or merchant ships were the main vehicles for smuggling antiquities out of Greece before and after WW II, including the famous New York kouros in the Metropolitan Museum.

Eight Months Later and a Riddle

In search of more information about the stolen marble head, I continued to read correspondence between Caskey and Morgan, whose main concern was the progress of work on the Stoa of Attalos and plans for its inauguration in the late summer of 1956. There I came across a letter titled “Confidential” that Morgan sent to Caskey on May 15, 1956 soon after the May Meeting of the School’s Managing Committee (AdmRec 318/5 folder 9). While in New York, Morgan paid a visit to Christine Alexander (1893-1975), Curator of Greek and Roman Art at the Metropolitan Museum. Morgan was on a mission (sent by Caskey) to see Alexander about a delicate matter, the return to Greece of some object. “Not knowing exactly what approach to take I said ‘I am at your service if you need me’.” Morgan was surprised not so much by the position Alexander took but “from the indomitable conviction with which she spoke.” “Her opinion is that the Metropolitan bought the article in good faith, that the Metropolitan’s funds are charitable funds, invested for the benefit of the people of New York, that it would be improper to ask the citizens of New York to pay for the carelessness of a local museum.” For a moment I wondered if they were talking about the Agora marble head.

But then Alexander further pressed her arguments by pointing out “that the figure had not been published in anything that seems to have reached this country [America], that when the figure was stolen, though everyone knows that such material drifts to the New York market, no notification was received by the Metropolitan nor so far she [knew] by any other museum or private collector.” It was obvious that she was talking about something else, a figure, not a head, that had been stolen from a Greek museum.

Morgan tried to counteract her arguments by saying that if he were a Trustee of the Metropolitan faced with such a problem “I would immediately dig into my own pocket and the pockets of my fellow Trustees to reimburse the city for the cost of the figure and restore it to its original position.” He further added that “this was the time for American institutions to make such gestures and [he] would strongly advise that it be done with the greatest possible attendant publicity.

To which Alexander strongly disagreed believing that it would have had the opposite effect. “Well, we made the rascals give up the swag” Morgan quoted her saying. Morgan promised Caskey that he would continue to press the matter: “I will do everything I can to effect what seems to me a solution indicated morally if not legally.”

I found Caskey’s response in Morgan’s files. In a long letter written from Lerna on May 27, 1956, about a host of issues concerning the reconstruction of the Stoa of Attalos, Caskey finally came to the matter of dispute with the Metropolitan Museum.

I consider it of the greatest importance that the piece be returned. I had not supposed for a minute that there could be any doubt about that. It was published in an extensive study with three clear photographs… And if the funds of the people of New York were misspent by accident –for goodness sake that is no reason for being righteous.

AdmRec 310/14, folder 10, Caskey to Morgan, May 27, 1956

The School’s good name was at risk: “… unless the bronze is returned promptly and gracefully, the good name of American archaeologists in Greece, and so of the School, is going to suffer a sharp blow. The French acted just right, asking no credit for returning the bronze that had been stolen (by others, of course) from Samos; and they received a lot of credit and good will from the Greek Ministry, and archaeologists. By contrast, we should look worse than Elgin,” concluded Caskey.

But what was the apple of discord? The only bronze figure that the Met acquired in 1955 was a small Hellenistic statuette of a rider wearing an elephant cap, and this seemed to have originated from Egypt. It does not seem that this was the figure that Greece wanted back and the Met refused to return. I have not been able to solve the riddle of the bronze figure. It also appears that the issue had not been resolved by April 1957, when Caskey, in another letter to Morgan, confessed that “just now I have had to report failure in my attempt to intercede in the matter of the missing work of art, about which you know, and this news of American irresponsibility [Caskey must be referring to the Met] made a really dismal impression on my Greek colleagues” (AdmRec 318/6, folder 2, April 18, 1957).

Afterthoughts

Although seemingly unrelated, the two cases point to the widening gap between art historians staffing American museums and field archaeologists, such as Caskey and Morgan, working in Greece in the 1950s. The former still operated under 19th century colonial terms, while the latter, especially Caskey, understood that following WW II there was a new world order in Greece to be taken into account and respected, despite his father having been Curator of Classical Art at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Although even he occasionally found the situation frustrating, he observed that both leftist archaeologists such as Meliades and conservatives such as Marinatos were justified in their belief that the foreign schools continued to be unreasonably critical of the work of their Greek colleagues.

It is of course easy enough for the [foreign] schools to criticize the Greek service in turn and point out its weaknesses, as well as the good that the foreigners do for Greece. But ultimately the Greeks are right; this is their country and they must make their own decisions.

Caskey confided to Morgan in late 1956 (AdmRec 318/6, folder 1, December 29, 1956)

As for stolen antiquities, such as the Hermes head from the Agora, the more publicity they receive the better it is. It is unclear how widely news of this loss circulated in 1955. Besides the short note in the London Times, I could not find a single reference in the newspapers.com database. The first time that a photo of the Hermes’ head appeared in a scholarly publication was in 1986 (Harrison 1986). Even if some of the large American museums were aware of its theft in the late 1950s, it is almost certain that, as curatorial staff retired or died (and with them institutional memory), the Hermes head moved from the top of the museums’ “hot list” to the bottom, when its photo was transferred to some institutional archive as an inactive record. It is laudable that the authors of the recent Hesperia article flagged its lost status several times in their essay. It remains out there somewhere, waiting to be repatriated to Greece.

References

Chatzi, G. (ed.) 2018. Γιάννης Μηλιάδης. Γράμματα στην Έλλη. Αλληολγραφία με την Έλλη Λαμπρίδη 1915-1937, Athens.

Harrison, E.B. 1986. “The Classical High-Relief Frieze from the Athenian Agora,” in Archaische und klassische griechische Plastik. Akten des internationalen Kolloquiums vom 22.–25. April 1985 in Athen 2: Klassische griechische Plastik, ed. H. Kyrieleis, Mainz, pp. 109–117.

Stewart, A., E. Driscoll, S. Estrin, N.J. Gleason, E. Lawrence, R. Levitan, S. Lloyd-Knauf, K. Turbeville, 2019. “Classical Sculpture from the Athenian Agora, Part 2: The Friezes of the Temple of Ares (Temple of Athena Pallenis),” Hesperia 88:4, pp. 625-705.

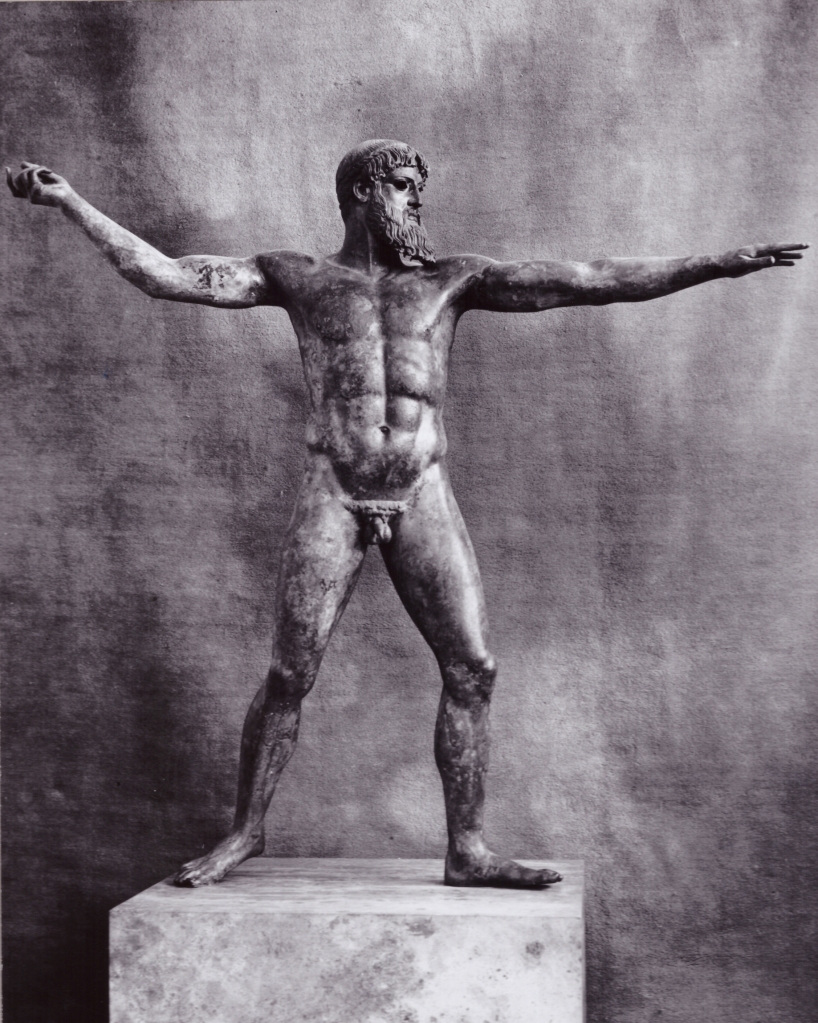

The Artemision Shipwreck: Sinking Into the ASCSA Archives

Posted: October 10, 2021 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Classics, History of Archaeology, Philhellenism | Tags: Artemision Jockey and Horse, Artemision Shipwreck, Artemision Zeus, Charles H. Morgan, George Hasslacher, George Mylonas, Georgios P. Oikonomos, Γεώργιος Οικονόμος, Philip R. Allen, Sean Hemingway 7 CommentsIn late 1928 the Greek and the international press published several articles and photos of a sensational archaeological discovery: a large bronze male statue found near Cape Artemision, in the north of Euboea. On central display at the Archaeological Museum in Athens since 1930, the statue is known to the public as the Aremision Zeus (or Poseidon).

Two years before, in the same area, fishermen had caught in their nets the left arm of a bronze statue that was also transferred to the National Museum in Athens. That discovery did not, however, provoke any further archaeological exploration in the area, most likely for fiscal reasons. But then in September 1928, the local authorities in Istiaia, a town in northern Euboea, were informed of illicit activity in the sea near Artemision. Acting fast, they sailed to the spot and caught a fisherman’s boat filled with diving equipment. Not only that, its crew had already pulled out the right arm of a bronze statue. A few days later the authorities were able to bring up from the bottom of the sea a nearly complete male, larger than life, statue. The first photos showed the armless statue laying on its back on a layer of hay (Note how the area of the genitals has been conveniently darkened in the newspaper photos so that the public would not be offended by the nudity of the statue.)

Read the rest of this entry »Financing the Reconstruction of the Stoa of Attalos

Posted: March 20, 2021 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Classics, Education, History of Archaeology, Philhellenism | Tags: Carl W. Blegen, Charles H. Morgan, Homer A. Thompson, John L. Caskey, Stoa of Attalos, Ward Canaday 4 Comments1946 marked the re-opening of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or School hereafter) in a country that had been devastated by war. In reading the official correspondence between the Greek Ministry of Education and the ASCSA, it becomes obvious that opening museums and the preservation of archaeological sites ranked highly on Greece’s list of priorities. With the launch of the Marshall Plan in 1947, Greece’s chances of success were also tightly connected with the development of tourism, and a large part of U.S. aid was streamlined in this direction.

“It is well known that travelers come to Greece chiefly for the purpose of seeing the ancient sites and visiting the museums of the country. In other words, the antiquities of Greece constitute a productive source of revenue capable of adding to the national treasury some 30 million dollars in the course of three years… No investment in the economy of Greece can match this for returns” wrote Oscar Broneer, Acting Director of the American School, on June 29th of 1948, in a petition of the School to the Industry Division of the Marshall plan for a $1,149,000 grant that would re-establish the Greek Archaeological Service.

ASCSA AdmRec 804/6, folder 4

Carl W. Blegen, the excavator of many prehistoric sites in Greece who succeeded Broneer in the Directorship of the American School (1948-1949) and had served as Cultural Relations Attaché at the U.S. Embassy in Athens in 1945-1946, also thought along the same lines. In an additional memorandum to the U.S. Ambassador in Athens, in August of 1948, Blegen underlined “the lamentable state of disrepair of the Greek museums,” which looked like empty shells (ASCSA AdmRec 804/6, folder 11). Blegen participated actively in meetings between the Economic Cooperation Administration (ECA) representatives and the Archaeological Service and helped with writing proposals. (The ECA was a U.S. government agency set up in 1948 to administer the Marshall Plan.) Since the American School could not receive direct funding from the Marshall plan, the only way to benefit from it was through collaboration with the Greek Government. The School hoped in this way to secure about $100,000 from the ECA through the Greek Government to supplement the cost of the construction of a museum that would store and display the growing number of finds from the Athenian Agora Excavations that had been accumulated since 1931. Before WW II, the School already had secured a grant of $150,000 from the Rockefeller Foundation to build a museum on the west side of the Agora.

Forced by the War to abandon their plans for an Agora Museum, the Americans resumed work at the Athenian Agora in 1947, conducting excavations at the proposed site, in order to begin construction. The 5th and 4th century B.C. houses and industrial workshops that they found were considered too important to be covered up, and a new site for the museum had to be found. After considering every possible location in the Athenian Agora for the museum, the Americans, following Homer Thompson’s suggestion, came to the conclusion that “another and in many ways preferable alternative would be to restore the Stoa of Attalos and install in it the museum, workrooms, and offices…” (ASCSA Annual Report 1947-1948, p. 29).

The draft of a program agreement between the ECA and the Greek Ministries of Coordination and Education included figures for the preservation of 34 monuments, and the reconstruction of the Stoa of Attalos was first on the list.

Read the rest of this entry »Tales of Olynthus: Spoken and Unspoken

Posted: October 1, 2015 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Classics, History of Archaeology, Women's Studies | Tags: Alan Kaiser, Charles H. Morgan, David M. Robinson, Eunice Stebbins, George Mylonas, Gladys Davidson Weinberg, Mary Ross Ellingson, Olynthus or Olynthos, plagiarism, Raymond Dessy, Rhys Carpenter, Richard Stillwell, Sexism, Walter Graham, Wilhelmina Van Ingen 7 CommentsIn memory of Barbara McManus (1942-2015)

In early March of 1928, David Moore Robinson (1880-1958), professor of archaeology at Johns Hopkins University, began large-scale excavations in Chalkidiki. His goal was to discover and investigate ancient Olynthus, the city that King Philip of Macedon had completely destroyed in 348 B.C. Since Olynthus had been abandoned after its destruction, Robinson was hoping to find temples, stoas, and other public buildings of the Late Classical period, without “any boring Roman stuff,” as one of the excavation participants observed. Until Robinson excavated Olynthus, the research focus of classical archaeology in Greece had been centered on the discovery of monumental public architecture and inscriptions. (For a biographical sketch of Robinson’s rich life, see https://dictionaryofarthistorians.org/robinsond.htm) Read the rest of this entry »

Barbarians at the Gate

Posted: September 1, 2013 Filed under: Archaeology, Classics, Education | Tags: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Charles H. Morgan, Emily Vermeule, Fulbright Foundation, Gertrude Smith, John L. Caskey 7 CommentsJack L. Davis, Carl W. Blegen professor of Greek Archaeology at the University of Cincinnati and former director of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (2007-2012), here contributes to the Archivist’s Notebook an essay about the history of the School’s admission exams.

Είναι οι βάρβαροι να φθάσουν σήμερα.

…

Και τώρα τι θα γένουμε χωρίς βαρβάρους.

Οι άνθρωποι αυτοί ήσαν μια κάποια λύσις.

The barbarians are coming today.

…

What will become of us without barbarians.

They were in themselves a kind of solution for us.

Constantine Cavafy, 1908

Are Greek-less barbarians knocking at the gate of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens?

Louis Menand (The Marketplace of Ideas, 2010), has written that there “are things that academics should probably not be afraid to do differently — their world will not come to an end…”. Yet institutions of higher learning are notorious for the “gate-keeping” mechanisms, procedures, and policies they employ to preserve the status quo. Central to the process of academic reproduction are examinations.

Exams have long puzzled me, particularly those administered by the American School of Classical Studies (ASCSA or “the School”). Forty years ago when I arrived as a student, I found in place a system that remains largely the same today. Candidates for the following academic year sit for admission exams. Of the 16 foreign schools in Athens that are recognized by the Ministry of Culture, ASCSA is, I think, the only one that controls membership in this way.

Members of the Managing Committee of the School, representing mostly Classics departments in nearly 200 universities and colleges in the United States and Canada, set the exams. There is one in Ancient History and another in Ancient Greek that all applicants must take, while students may choose between a third in Ancient Greek Literature or in (pre-Byzantine) Greek Archaeology. The prize is a yearlong fellowship in Athens that includes room and board. Read the rest of this entry »