Becoming: Bert Hodge Hill, 1906-1910 (Part I)

Posted: January 1, 2024 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Crete, History of Archaeology, Mediterranean Studies, Modern Greek History, Uncategorized | Tags: Archaeology, Athens, Bert Hodge Hill, europe, George W. Elderkin, greece, James R. Wheeler, Kendall K. Smith, Mochlos, Richard Berry Seager, Theodore W. Heermance, travel 8 CommentsThe re-discovery of a small cache of old photos depicting students at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or School hereafter) from 1907-08 inspired me to write about the first years of Bert Hodge Hill’s directorship at the School. [1]

The photos depict four men and one woman: George Wicker Elderkin (1879-1965), Kendall Kerfoot Smith (1882-1929), Charles Edward Whitmore (1887-1970), Henry Dunn Wood (1882-1940), and Elizabeth Manning Gardiner (1879-1958). Of the five, Elderkin, Smith, and Wood were second year students at the School. In 1908, Elderkin, who already held a PhD from Johns Hopkins (1906), succeeded Lacey D. Caskey as Secretary of the School, a position he held for two years (1908-10). Smith came to the School in 1906 holding the Charles Eliot Norton Fellowship, established by James Loeb in 1901 for Harvard or Radcliffe students. Wood, a trained architect with a BS in Architecture from the University of Pennsylvania, was the second recipient of the Fellowship in Architecture (1906-08) that was funded by the Carnegie Institution in Washington.

Of the new students, Whitmore, another Harvard man, was the Charles Eliot Norton Fellow for 1907, and Gardiner, the only woman in the photos, was a graduate of Radcliffe College (1901), with an MA from Wellesley (1906), and a recipient of the Alice Palmer Fellowship that supported female students.

An Untimely Death

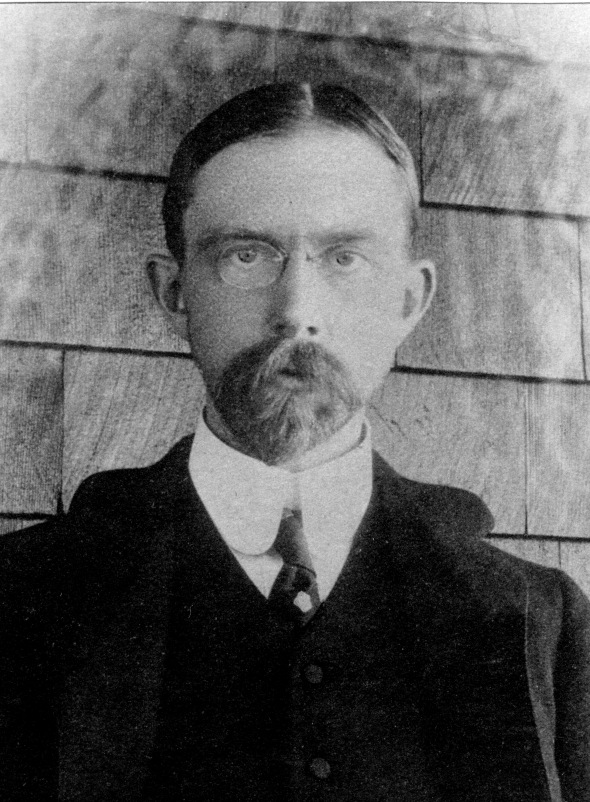

Bert Hodge Hill (1874-1958), an Assistant Curator at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (MFA Boston), succeeded Theodore Woolsey Heermance in the School’s directorship after Heermance died unexpectedly in Athens in September 1905. Heermance, who held a PhD from Yale University, was about to start the third year of his directorship when he became sick with typhoid. Within a few days, the 33-year-old man was dead, leaving the academic community in shock. His body was shipped to his mother in America and buried with the rest of the Heermance family. (Heermance in the photo. ASCSA Archives, Theodore W. Heermance Papers)

The Annual Professor William N. Bates and the Secretary of the School Lacey D. Caskey assumed the duties of the directorship for 1905-06. At the annual meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America in December 1905, a special committee of the School’s Managing Committee was charged with the selection of the new director. In the Annual Report (1905-06) we read about the appointment of a young but promising scholar, Bert Hodge Hill. Hill had been a student and a Fellow of the School in 1900-03. James R. Wheeler, Chair of the Managing Committee, publicly praised Hill, despite his personal reservations.

Hill’s biggest supporter for the directorship, Samuel E. Bassett, Professor of Classics at the University of Vermont (the alma mater of Hill) highlighted the many positive features of the candidate (clear headed, independent thinker, thorough archaeological training, good reader of character), and downplayed his one negative trait (which ironically tortured Hill for the rest of his life and caused his dismissal from the School’s directorship twenty years later): Hill’s inability to deliver timely reports or to publish.

“His mental activities are so alert that he always sees something new in whatever he is studying, and the multiplication of these new subjects has so far prevented his publishing anything. He is too conscientious to publish anything before he has done all in it that he can, and so he has given the impression to some (Prof. Wheeler especially I fear) that he allows himself to be drawn off from the subject in hand […]. Hill does not always appreciate the need of promptness, it is true, and this way has contributed to the delay in bringing out what he has on hand.” Bassett found this defect a small matter which could be balanced by Hill’s other qualities (AdmRec 310/3 folder 3, Bassett to Wheeler, Oct. 22, 1905).

Other people’s opinions about Hill are preserved in the School’s Administrative Records. Angie Clara Chapin, Professor of Classics at Wellesley College, wrote to Wheeler: “A little informal inquiry from two or three who are competent to judge brings out the impression that he [Hill] is scholarly in his work and of agreeable personality and is highly thought of at the Museum in Boston as well as here [Wellesley]. He is, however, spoken of as ‘very boyish,’ and while not at all ungentlemanly, perhaps rather unconventional.” (Adm Rec 301/1 folder 1, Dec. 12, 1905).

Despite Wheeler’s and others’ reservations, Hill beat out other candidates such as Charles Weller and Walter Miller. Hill’s appointment was approved at the May meeting of the Managing Committee but with one condition: Hill would not maintain a formal connection with the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Hill could offer general advice and one month’s work during the summer but he could not keep his position or title as Curator. “The reason is this: During the years when the Museum bought Greek antiquities freely, various objects of value passed out of Greece and went eventually to the Museum. No suspicion, of course, then attached to the School and no blame to the Museum, but the Committee felt that, if an official connection were to exist publicly between the two institutions, it would be difficult to avoid creating a doubt in the minds of the Greek authorities, with whom it is of first importance for the School to be on friendly terms” wrote Wheeler to Hill on May 12, 1906 (ASCSA Archives, Bert H. Hill Papers, box 5, folder 1). [Bert H. Hill in the photo, ca. 1906. ASCSA Archives.]

Becoming Director

Hill arrived in Athens in September 1906 in the company of Caskey. He was 32 years old. Within days he called on the U.S. Minister, John Brinckerhoff Jackson, to ask his advice about the social duties of the School’s Director. Jackson had several years of experience in Greek matters (1902-07) and advised “formal calls on diplomats, ministers of education and foreign affairs, marshals of households of Crown Prince, Prince Nicholas and Prince Andrew, Greek archaeologists and chief ephors.” Georg Karo of the German Archaeological Institute should be called upon as well as Wilhelm Dörpfeld, “he [Karo] Dörpfeld’s colleague, not subordinate.” Following Jackson’s advice Hill shortly called upon Panayotis Kavvadias (1850-1928), the powerful Director General of Antiquities, who attempted to intimidate Hill by asking his age, implying that he was too young to head the American School (Bert H. Hill Papers, Diaries, entry for October 2, 1906). A day later Hill was lunching at the American Legation as a guest of Mr. Jackson together with the British Minister Sir Francis Elliot, the U.S. Consul General George Horton, Admiral Willard Brownson and a handful of other U.S. Captains who were with their ships in Piraeus, as part of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet, and on their way to Egypt. Hill noted that the occasion required a frock and high hat which he must have brought with him from America.

The School officially opened on October 1. It was a full house with sixteen members: eleven men and five women. Hill proudly stated that the membership had “equaled the largest previous enrolment -that of 1900-1901,” including returning members such as Louis Francis Anderson, professor of Greek at Whitman College, and Minnie Bunker, a high school teacher in Oakland, who both had been students of the School in 1900-01; PhD holders such as Clarence Owen Harris, George W. Elderkin, and Albert Ten Eyck Olmstead; second year fellows such as Kendall K. Smith, the Charles Eliot Norton Fellow, and Henry Dunn Wood, recipient of the Carnegie Fellowship in Architecture, and a younger crowd such as Florence Mary Bennett, Eva Woodward Grey, James Samuel Martin, Louis Earle Rowe, and Raymond Henry White.

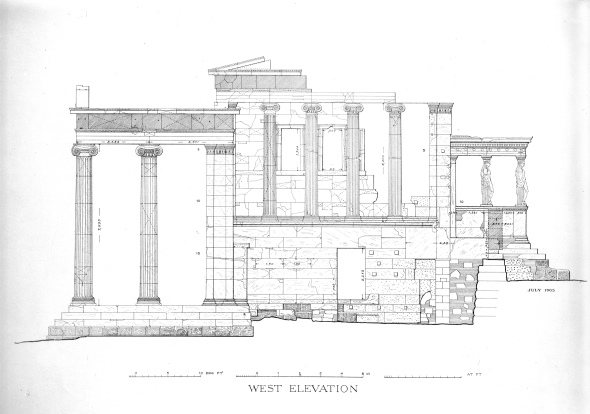

In addition to being responsible for the School’s academic program, Hill inherited from Heermance two projects that the School’s Editorial Committee was anxious to see completed soon: the publication of the Erechtheum and a special Bulletin on the Excavations at Corinth (Annual Report 1904-05, 11). Taking advantage of scaffolding that architect Nikolaos Balanos had erected about different parts of the Erechtheum for its restoration, Heermance with the endorsement of James R. Wheeler received permission from the Ephor General of Antiquities to measure and study the building with a view to a new publication. The School assigned the task of drawing to Gorham P. Stevens, a graduate of MIT and the first recipient of the Fellowship in Architecture. (In 1903 the Carnegie Institution of Washington awarded the School an annual fellowship to support the production of architectural plans for Corinth and other School projects.)

“The School has never entered upon a more useful and important undertaking than this. The book is sure not to be only a thing of beauty, but a matter of permanent scientific value” commented Wheeler in his report (Annual Report 1903-04, 13). According to the same report, Dörpfeld “put at Mr. Stevens’s disposal his entire store of knowledge of the Erechtheum and its problems” (Annual Report 1903-04, 22).

Heermance had planned to write most of the sections himself, except for the chapter on the sculpture which he entrusted to Harold N. Fowler. To facilitate the completion of the project after Heermance’s sudden death, the School’s Editorial Committee decided to go on with a collaborative publication (sections assigned to L. D. Caskey, H. N. Fowler, J. M. Paton, and G. P. Stevens) which did not appear, however, until two decades later (1927). Hill was not included in the publication even though its authors relied on him for new measurements and “whose suggestions have sometimes been adopted verbatim.”

Stevens’s measured drawings were exhibited at the School during the Archaeological Congress in the spring of 1905. From January until March 1906, they were on display at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. “What shall be done with the drawings after March 1st, the date when the Museum exhibition of them closes?” asked J. R. Coolidge Jr., the interim director of the Museum (AdmRec 310/1 folder 1, Coolidge to Wheeler, Feb. 19, 1906). Shortly after, Coolidge offered $1,000 to buy the drawings and photos which had been exhibited at the Museum, and “if the drawings shall pass into the possession of the Museum before the book on the Erechtheum appears, the Museum shall allow no reproduction of them by anyone before the book is on the market or until the lapse of five years from this date.”[2]

The Bulletin on the Corinth excavations did not fare better than the Erechtheum publication. It was briefly replaced by plans for another publication, titled Papers on Corinth, which also never took off. The School continued its excavations at Corinth with Hill reporting on them at the School’s Open Meetings in Athens, and occasionally at the Annual Meetings of the Archaeological Institute of America, but almost never in writing.

Instead, the enlargement of the School’s building became the main topic of concern in the School’s Annual Reports after 1907. The School needed more library space, additional rooms for students (not to mention that there were no baths) and faculty, and a much-desired common room. The enlargement of the School was finally achieved in 1915, thanks to the generosity of James Loeb who funded half of the construction cost (AdmRec 310/2 folder 5, Wheeler to Hill, Dec. 9, 1907).

Fighting Death in Athens

Living in Greece in the early years of the 20th century was not safe. Malaria and typhoid fever were almost endemic. In the winter of 1906, Hill, Caskey, Smith and Wood came down with malaria contracted on a trip to Phocis and Boeotia (Annual Report 1906-07, 12). In the fall of 1907 Elderkin succumbed to malaria, eventually becoming delirious from the high fever. Hill, however, was thankful that “it was rather malaria than something worse.” Within days, the Annual Professor Edward B. Clapp was also struck with fever. The School’s doctor, Dr. Makkas, managed to secure him a nurse from the Children’s Hospital, “one of the νέαι Αμερικανίδες” (Greek nurses who had just returned from four years’ training in American hospitals). Caskey, who was taking care of Elderkin, contracted malaria for a second time within a few months of the first incident. To fight malaria Hill proposed placing screens on the windows: “screens will be difficult to secure, well fitted, and we shall doubtless find them disagreeable when we have them; but I intend to try placing them in all the sleeping-room windows. Doubtless, I shall have my adventures as an inventor of window-screens here in a land where such things are quite unknown” Hill wrote to Wheeler (AdmRec 310/2 folder 5, Nov. 20, 1907).

In the spring of 1908, one of the five people in the cache of photos that inspired this essay, Kendall K. Smith, became sick with typhoid fever (AdmRec 310/2 folder 6, Hill to Wheeler, May 11, May 22, and May 26, 1908). Hill suspected that the infection had come from consuming lettuce “which we ate very freely in April. It will be forbidden hereafter.” For many days his temperature ranged from 102F to 106F. His case was so serious that his father had to rush to Greece. Soon after, Smith, who was Hill’s first choice to replace Caskey as the School’s Secretary, returned to America to convalesce at home. Hill settled on Elderkin for the Secretary’s position. Although a better qualified candidate, at least in paper, Elderkin was not Hill’s first choice.

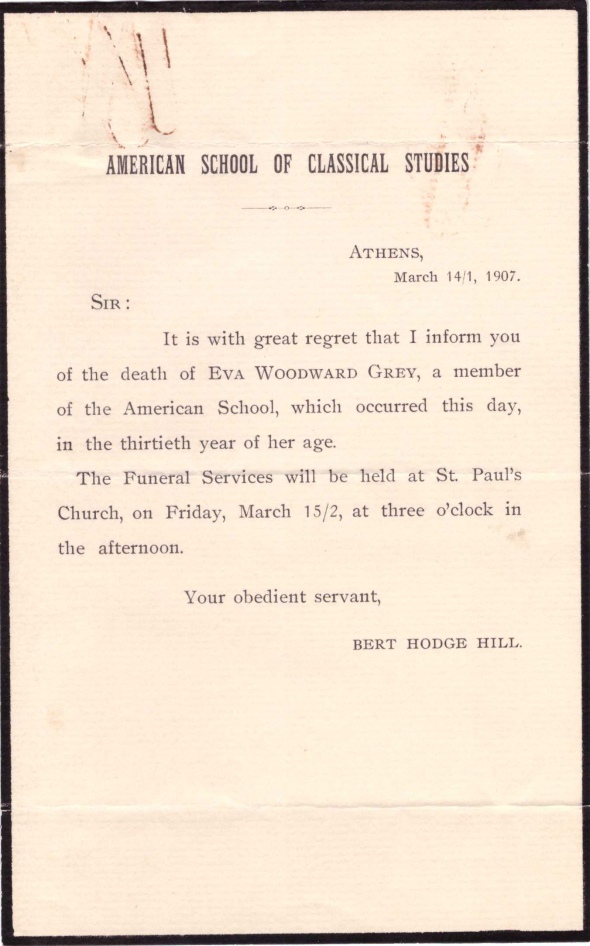

Heermance’s death was followed by that of Eva Woodward Grey from acute uremia in March 1907. A graduate of Cornell University (1898) and a high-school teacher, “her coming to Greece had been the fulfillment of a long-cherished hope, and she was one of the most earnest and eagerly interested members of the School” Hill reported (Annual Report 1906-07). It must have been extremely stressful for Hill to have to deal with the death of one of the students within months of assuming the School’s directorship. After telegraphing Grey’s family and inventorying her personal things, “Mr. Horton and I ordered a coffin, with no word coming from America I took the responsibility of deciding that the body should not be embalmed, Mr. Horton strongly advising against embalming because of the great difficulties encountered two years ago” [Hill is referring to Heermance’s death]. Hill and Horton secured a burial permit and a plot in the First Cemetery “near the graves of Professors Merriam and Lolling.”

Hill acted fast because according to the Greek law the burial had to take place within twenty-four hours; in addition, he had not heard back from Grey’s father. Hill and Horton made the decision to spare the family the high cost of embalming “in view of what Miss Grey had said about her means” (AdmRec 310/2 folder 5, Hill to Wheeler, March 16, 1907]. At least Hill had the Consul General (Horton) advising him on such difficult matters. “The attendance at the church was large, and about fifty persons followed the body to the cemetery […]” Hill wrote. Soon after Grey had been buried, the family telegraphed asking that their daughter’s body be embalmed and placed in a sealed casket, to be shipped to America. It was too late, however. The Greek law did not allow exhumation until three years had passed after the burial.

With all this sickness, there was concern among the members of the Managing Committee that the School was not a safe place to send students. Hill tried to defend the School by explaining that “Miss Grey’s illness [uremia] had no possible connection with conditions in Greece. Malaria and influenza have been the only other maladies[…]. The malaria is Greek, I admit, but not due to the American School’s own local conditions” (AdmRec 310/2 folder 5, Hill to Wheeler, April 26 [1907]).

In October 1907, the archaeological community lamented one more death in Athens, that of German archaeologist Adolf Furtwängler. “Greece, apparently, cannot be blamed for Professor Furtwängler’s illness, at least not wholly; suffered from dysentery this summer before he came down here [Aegina]. In fact, his familiarity with the trouble seems to have made him underestimate the seriousness of this last attack. He kept at work and continued to eat local food in Aegina, until last Saturday. Then he consented to be brought here; but it was too late” (AdmRec 310/2 folder 5, Hill to Wheeler, Oct. 10, 1907).

The Mochlos Case: Treading on Thin Ice

In April 1907, Hill informed Wheeler that his report for the May Managing Committee meeting would be late because he was “so crowded with small time-consuming duties.” He also noted Seager’s visit. Richard Berry Seager (1882-1925), according to his biographers “one of the last of the wealthy ‘collector-excavator-historians’,” was excavating on the small island of Pseira on the north coast of Crete, with funding from the American Exploration Society in Philadelphia. [4] (Suggested reading: Phantom Threads of Mothers and Sons.)

Back then, American museums and societies were eager to sponsor excavations on Crete, because it was an autonomous state (1898-1913), under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire and the supervision of the Great Powers; with its own archaeological law, the Cretan State was more “generous” in the matter of exporting antiquities. Because of problems between the Exploration Society and Seager, Hill conveyed to Wheeler Seager’s new idea: “There is another Cretan site which he regards as very promising and I have authorized him to apply for a permit in the name of the School -no obligation involved except that of being interested in his work” (AdmRec 310/2, folder 5, April 22, 1907).

Having secured a permit in the name of the ASCSA, Seager crossed over to the small island to do some testing in the summer of 1907: “… everything points to a good town site rather like the one I have been digging this season in Psyra [sic]. The earth is only 1 to 3 metres deep […] We found several vases in the two days we worked. The best one […] Mackenzie agrees with me… is the best LMI vase that has ever been found. It is of large size and is wonderfully preserved. […] If Mochlos continues as well as it has begun it ought to be a most valuable site and be worth at least two seasons work.” To entice the School’s interest in the site and knowing Hill’s past connection with the MFA Boston, Seager added: “Also as the Cretan museums get more and more crowded the more things they allow to leave the island. So there might be something really worth sending home […]” (AdmRec 310/2, folder 5, Hill to Wheeler, October 7, 1907).

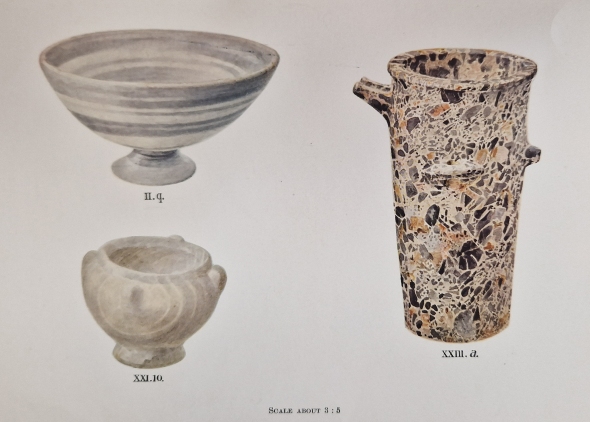

Seager included a watercolor by Émile Gilliéron (1850-1924) of the LMI jar he found in 1907 in his article “Excavations on the Island of Mochlos, in 1908,” published in AJA 13, 1909, 280, pl. VI. Eighty years later while digging the Artisan’s Quarter at Mochlos, Jeffrey Soles and his team discovered another one of these large “lily jars,” a watercolor of which, this time by Doug Faulmann, featured as frontispiece in Mochlos IA. [4]

Seager communicated through Hill that he could supply $1,000 himself but he needed the School to fund the remaining sum, from $500 to $800. However, confusion arose when Seager secured $600 from a Mrs. James Bowlker, who had a connection with the Egyptian Department of the MFA Boston (I remind you once again of Hill’s connection with that museum). Arthur Fairbanks, the new Director of the MFA, wrote to Hill: “I understand that officially you know nothing about our connection with the expedition and I am writing Mr. Seager as though we are dealing directly with him and not with him through you”(quoted in Hill to Wheeler, January 28, 1908, AdmRec 310/2, folder 6).

Aware of the MFA’s connection to the Mochlos excavation, Wheeler confirmed:

“Our situation therefore is that the School gets the concession, entrusts the work under it to Seager […], we leave the disposition of the finds entirely in his hands. If he arranges with the Cretan authorities that some of them go to Boston, it is none of our business. In any publication the School name should of course appear in some way […]. We may be skating on rather thin ice, but we shall have to trust to your discretion to make things appear in a proper light” (Bert H. Hill Papers, Box 5, folder 1, Wheeler to Hill, Jan. 24, 1908).

As Seager predicted, the excavation of Mochlos proved to be a success. In late June of 1908, Seager wrote: “I know you will be glad to hear that Mochlos as a dig has been a far greater success than I had dared to hope. […] The town site for the first month was singularly unproductive but our first stroke of luck was a horde of six bronze basins rather like those found at Knossos some years ago. There is a lot of pottery from the town houses none of it very striking but good of its kind. Perhaps it is a good thing as it won’t tempt the Cretan Museum and I may manage to persuade them to let me have a good lot for the Boston Museum. Towards the end of the season we found the early cemetery which was a very rich one quite the best I should say that has been found so far in Crete. There were five large tombs evidently of important families and about twenty smaller ones containing a number of bodies. One of the large tombs was literally filled with gold ornaments. Diadems, pins, chains, etc. You will realize the importance if this when I tell you that the graves are for the most part Early Minoan II and III. […] Last but not least are the stone vases which have been a revelation to everyone who has seen them. They are all in bright colored marbles, alabaster, breccia, various kinds of soapstone and what seems to be serpentine. The shapes are very graceful and there are in all at least 150. […] Mr. Evans came up from Knossos for a few days and said that he never could have believed that E.M. II and III could have produced such fine gold chains or such stone vases” (Bert H. Hill Papers, Box 4, folder 5, Seager to Hill, June 30, 1908). A few months later, Arthur Evans sent a letter to Wheeler praising Seager’s work at Mochlos as “thoroughly well done from the scientific point of view” but also criticizing the School for not having sufficiently backed him up with an architect or a surveyor” (AdmRec 310/1, folder 2, Sept. 20, 1908).

Seager continued: “I had almost forgotten the best single object of the whole season. Lying near the surface and badly destroyed lay a few Late Minoan I burials and from one of them comes a gold signet like those from Mycenae with a religious scene. A goddess in a serpent boat containing her sacred tress is arriving at a pillar shrine which stands on the shore. It is in perfect preservation and in the field are one or two curious symbols that I believe are new to this class of rings. It is one of the best of its kind and might well be said to be worth the whole expense of the dig (Bert H. Hill Papers, Box 4, folder 5, Seager to Hill, June 30, 1908).

On August 14, 1908, Seager dispatched another letter from Herakleion stating that he had had a hard time in the matter of exporting antiquities from Crete. “They [the Cretan authorities] are keeping all the things for Greece as of course they now think annexation is very close. […] However truthfully, I can advise no one to subscribe money to Cretan excavations under the present circumstances unless they do it with no expectations as to the increasing of home collections”. Although the formal unification of Crete with Greece did not happen until 1913, 1908 marked the end of an era. The American museums could no longer fund excavations on Crete with the expectation of enriching their collections with new finds.

“Richard Seager may seem to be an anachronism, but he was a product of his time. Modern archaeology grew out of the collecting zeal and passion with history of nineteenth-century amateur antiquarians. […] In the final analysis, Seager remains an enigma. He pursued archaeology as an amateur with no formal training […]. By the time he was thirty, he was regarded as a major scholar by the leading men and women in his field. […] At his death, he was remembered for his excavations and publications, for his generous gifts, and for his friendships. However, there was no one to carry on his archaeological work in Crete. He had no students, no young assistants, and no professional associates,” concluded Marshall Becker and Phil Betancourt, Seager’s biographers. [4]

I would add that Hill was also a product of the same time. But Hill lived much longer than Seager, and by having a formal affiliation with a recognized institution he was forced to respond to the calls of the new era that condemned illegal exportation of antiquities. Hill’s directorship lasted twenty years, the longest in the School’s history. But back in 1910 his reappointment for a second five-year term was not as unanimous as the Annual Report of 1910-11 implied. I will be exploring the second half of Hill’s first term as well as the (after)lives of the five students featured in the photos in my next post.

Notes

[1] The photos in the envelope had been identified by their owner or creator, but there was no obvious connection with any of our collections. The envelope which was stored in a drawer with miscellaneous material carried the handwriting of my predecessor, Carol Zerner. They had either been sent to her by the descendants of one the people depicted in the photos, or, more likely, they had been removed from the papers of Bert Hodge Hill.

[2] In the Preface of the Erechtheum volume published in 1927, the editors noted that the “The original drawings are in the School of Applied Arts of the University of Cincinnati.” Stevens’s drawings are lost, despite the efforts of members of the UC Department of Classics to find out where the drawings ended up after the School of Applied Arts was dissolved. I do not know yet how they ended up in Cincinnati since the MFA Boston was ready to buy them.

[3] Soles, J.S. 2003. Mochlos IA: Period III. Neopalatial Settlement on the Coast. The Artisans’ Quarter and the Farmhouse at Chalinomouri, Philadelphia

[4] Becker, M. J. and P.P. Betancourt, 1996. Richard Berry Seager: Pioneer Archaeologist and Proper Gentleman, Philadelphia, 191-192.