“All Americans Must Be Trojans at Heart”: A Volunteer at Assos in 1881 Meets Heinrich Schliemann

Posted: August 1, 2015 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, History of Archaeology, Mediterranean Studies, Philhellenism | Tags: Assos Excavations, Charles Wesley Bradley, Eliot Norton, Francis H. Bacon, Heinrich Schliemann, Mytilene 6 CommentsCurtis Runnels, Professor of Archaeology at Boston University, here contributes to The Archivist’s Notebook a story about the discovery of a personal diary of a young American who participated in the Assos excavations in 1881 and had the opportunity to meet Heinrich Schliemann. In addition to doing fieldwork and publishing extensively on Palaeolithic archaeology in Greece, Runnels is also the author of The Archaeology of Heinrich Schliemann: An Annotated Bibliographic Handlist (Archaeological Institute of America; available also as an ebook from Virgo Books). See also his most recent post about Schliemann, titled “Schliemann Turns Over a New Leaf.“

“He was an American citizen himself—and believed that all Americans must be Trojans at heart.” The line above describes Heinrich Schliemann and comes from the personal diary of a young American who met Schliemann at Assos in 1881. Boston native Charles Wesley Bradley (1857-1884) graduated from Harvard in 1880, having studied classics and philosophy with Charles Eliot Norton, the founder of the Archaeological Institute of America and the driving force behind the first American excavations in classical lands at the site of Assos in northwestern Turkey. Bradley initially intended to read for the law, but chose instead to be one of the 50 applicants for a volunteer position on the Assos Expedition, leaving Boston in March of 1881 to join the group in Turkey. The project was directed by Joseph Thatcher Clarke, assisted by Francis H. Bacon, and the volunteers included Charles H. Walker, Joseph S. Diller, Edward Robinson, William C. Lawton, John H. Haynes, Maxwell Wrigley, and Norton’s eldest son, Eliot. (On Clarke, Bacon, and Assos, see also Allen 2002, pp. 63-92).

A diary kept by Bradley during his time at Assos has recently come into my possession along with some of his essays and manuscripts. These materials reveal Bradley’s ambitions to work up his archaeological and travel experiences in publishable form. There are well-crafted accounts of Bradley’s travels in Greece and Turkey that include descriptions of daily life, private homes, inns, and cafes, along with costumes, people, and local customs. They are engaging, often humorous, and very well observed. He also penned essays on the excavations at Assos and miscellaneous historical and archaeological sketches. Some of his essays were published in newspapers both before and after his return to Boston, for example his account of a visit to the Iliou Melathron, the Schliemanns’ home in Athens (“Dr. Schliemann at Home”) appeared in The New York Times on April 23, 1882.

Bradley’s diary chronicles his adventures from his departure from Boston until the end of June, 1881. It is about 6.5 X 4 inches in size, and contains about 260 leaves. It is legibly written in ink and pencil and illustrates Bradley’s intention to record his experiences so that he could work them up as literary productions later. The entries are artfully composed with few abbreviations, corrections, or spelling errors. He wrote carefully, giving attention to the formal composition of the entries, and it is evident from the orthography, the dating of the entries, and other clues such as the changing use of pen and ink, that they were composed within hours or at most a day or so of the events described. The charming sketches often include humorous descriptions of his surroundings and companions. Bradley must have been a good travelling companion. The personality that emerges from the diary is that of an intelligent, resourceful and amiable young man, much like Edward Lear of a generation before, with whom he shares a dry wit and an adaptable attitude towards the rigors of travel. This can perhaps be best appreciated from some typical passages. Bradley and his comrades, like most Aegean travellers in those days, were tormented by mosquitoes, fleas, and bedbugs. He often referred to these problems, but bore them philosophically:

Friday. May 27.

We found Eliot keeping house at the “bug-palace” or “entomological museum” as our residence in Mytilene is called. He came out here to collect the fauna and flora of the region. He has not found much in the flora line except thistles, but the insect branch of the animal kingdom has proved exceedingly fruitful.

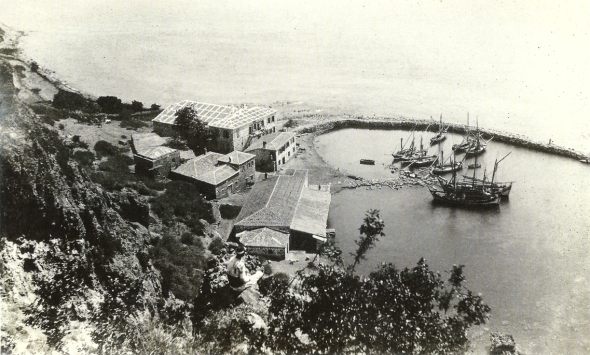

The volunteers lodged in two small rooms in the little port town of Behram, which was nestled in the ruins of Assos. Their accommodations were bereft not only of comforts, but also of necessary supplies. These had to be obtained from the island of Mytilene, 30 miles away by sail. The expedition used a small sailing skiff to make the supply runs. Although Bradley could sail, many of the other volunteers could not. The following passage reveals Bradley’s sense of humor in these situations.

The Ottoman Harbour at Assos. The American expedition rented two rooms in one of the warehouses as their living quarters. Source: Ousterhout 2012

Saturday. May 28.

[Returning by boat from Mytilene to Assos]. I have been obliged to ship a new crew consisting of one able-bodied landsman named Eliot Norton. He had to be purified on account of a previous voyage on a Turkish mame-boat [sic] infested by fleas. On going out of the harbor the crew showed signs of insubordination. There was considerable discussion as to which of us was captain and which of us was crew. Meanwhile the boat, left to her own resources, came near capsizing. This point settled, the crew became interested in a wind. [T]he wind is fair and we fly along. Crew goes to sleep. Wakes up with an appetite and proposes to eat up all the provisions and go back to Mytilene for more. This not being agreed to, he presents an alluring scheme to become pirates and prey upon the Greece merchantmen. Not seconded. Get rid of crew by sending him forward to look out for rocks.

Bradley participated in the first season at Assos, but, like most of the other volunteers, he did not return in 1882, presumably because of mismanagement by Clarke, and perhaps because of the vermin, malaria, and malnutrition that dogged the volunteers in 1881. It is not known what Bradley did until his return to Boston in September, 1882, but the titles of the surviving manuscripts suggest that he travelled in Turkey (“A Tramp in the Troad” and “A Provincial Town in Turkey”) at least in part to study archaeology (“Archaeological Explorations in the Troad” and “Archaeological Discoveries in Phrygia”), with periods of residence on Mytilene and in Athens, and travel in Europe (“The Carnival in Rome”).

Schliemann with his pith helmet, 1880s. Not as fat as Bradley described him in his diary. Source: Heinrich Schliemann Papers, American School of Classical Studies at Athens

Of particular interest is Bradley’s, probably unpublished, account of meeting Heinrich Schliemann written in the hours following the events that are described.

Monday. May 16.

Excitement in the port of Behram [Assos]. Five horses are winding along the steep path that plunges down the gully in the precipice. The party reach [sic] the bottom—a runner, a dragoman, a gendarme, Schliemann! Yes, here is the discoverer of Troy in the very land where he seems to belong—a short fat man, much burnt by the sun. He wears a pith hat, flannel shirt, and gray travelling suit, and a huge pair of glasses which make him look much more like an owl than the earthen jugs in which he think[s] he detects the features of that bird. We show him where to take his evening bath, and after he has refreshed himself with supper he visits us in our room. His conversation made the evening pass quickly.

“I am on my way,” he said, “locating the cities mentioned by Homer. This Assos is probably Chrysa. You are doing good work here, just the work for young men. But it wouldn’t do for me. I am all for prehistoric sites. I am getting along in life—have only a few years more to live—and shall give them all to prehistoric work. I would like to dig at Tiryns, but it’s no use. The Greeks were so jealous of me when I found the Mykenae treasure that they would have liked to crucify me. It’s no use—they won’t let me dig in Greece now. I wanted to dig at Sardis too, but another man [probably George Dennis] got a firman [permit] before me, on condition that he would dig every month. He was unable to raise money for the work, so now he goes out and digs one day in each month, and so still keeps his firman, hoping for funds in time. Sardis is a grand field. It’s a pity I couldn’t have it. Old Lydian inscriptions would probably be found there—and these would be a great gain to archaeology, for the language was lost before Strabo’s time.”

We asked about Ithaca.

“There is no hope of finding anything there,” he answered. “I have been over the ground thoroughly. The rain has washed everything away. But I have hopes of Andros—there must be something in Andros. And there are more tombs still at Mykenae.”

He spoke very freely about his trouble with the Turks.

“When we were working at Troy, I used to throw away as worthless many things that the workmen brought me, and then pick them up afterwards when no one was looking. When we came to the great treasure, I called the workmen to dinner, and dug it out myself. The Turkish government sued me afterwards at Athens for not keeping my contract and giving them the stipulated share of the treasure. They won the suit, and the court awarded them 10 000 francs. I sent them 50 000 francs, accompanied by a request for a new firman. And I got it.”

Dr. Schliemann was evidently thoroughly engrossed by his work. He could think and talk of nothing else. Indeed, he did not seem to hear well any remarks which bore no reference to it. He spoke of his wife as a great enthusiast for Homer, saying that both he and she were lovers of the Trojans and of Hector. And when he left us, bidding us good-bye, for he intended to start at daybreak next morning, he said he was always glad to meet Americans. He was an American citizen himself—and believed that all Americans must be Trojans at heart.

Schliemann (fifth from left) at Troy, ca. 1880s. Second from left is Schliemann’s architect, Wilhelm Doerpfeld. Source: Heinrich Schliemann Papers, American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

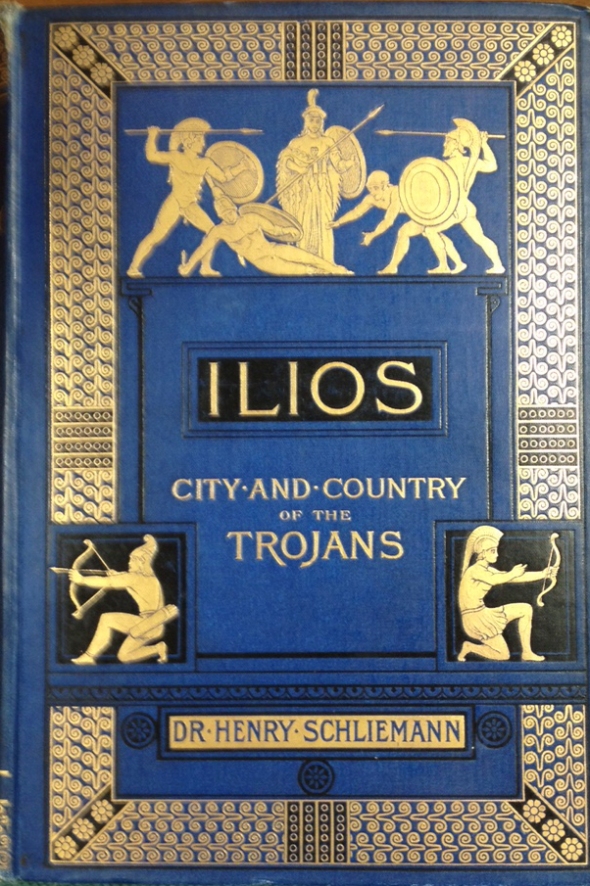

Bradley would use the final lines from this account, somewhat reworked, in his New York Times letter “Dr. Schliemann at Home,” which ends with Schliemann telling his guests “Americans sympathize with me in my work. They are fond of the Trojans, like Mme. Schliemann and myself, who love the Trojans and Hector. It seems to me that all Americans must be Trojans at heart.” Perhaps Dr. Schliemann liked to repeat himself on those occasions when he met Americans, or perhaps Bradley could not resist taking a memorable quote from his Assos diary and fitting it in here. During his visit to Assos, Schliemann repeated some of the now well-known stories, such as being sued by the Ottoman government in an Athenian court for his violations of his permit requirements, and there are also some new stories. One wonders what made Schliemann so sure that Andros would be worth investigating, or how much he really longed to spend the rest of his years at Sardis? And what are we to make of his statement that the Greeks wanted “to crucify him” and “wouldn’t let him dig in Greece.” On that point, Schliemann had conveniently forgotten that he had just completed his second season of excavations at Orchomenos in Boeotia in April. Finally, we have again the confirmation, if one were needed, that Sophia Schliemann was not present at the discovery of Priam’s Treasure (contra the romantic story in the introduction to Schliemann’s Ilios, which was published late in 1880, and a copy of which the Assos volunteers happened to have with them): Schliemann did not mention Sophia to the attentive Bradley, but describes how he “dug it out myself.”

Bradley was clearly impressed by his meeting with the great man, but he was no starry-eyed acolyte. Only days later, he notes in his diary that

Saturday. June 18.

To-day we have been reading the Ilios. Schliemann’s preface is the most ludicrous autobiography extant. We are told all about the love affairs of his childhood. One tearful episode was the interruption of a clandestine interview with his six year old [sic: the preface says fourteen] inamorata by the young lady’s parents. The subsequent history of this lady and her present address are also given. This is doubtless with the view of conferring immortality upon her. The Ilios is thus romantic, but it does not pretend to be witty.

According to a moving obituary by his friend Arthur Wentworth Hamilton Eaton, Bradley returned to Boston in September of 1882 to pursue a career in literature. It is to be regretted that he did not succeed, as the surviving manuscripts are evidence of his talent as a writer. Only two years after coming home, suffering still the effects of malaria contracted while at Assos, he died of a “fit of mental despondency” in September, 1884. He was 27 years old.

*A Note by Natalia Vogeikoff-Brogan

After reading Curtis’s narrative, I remembered that the ASCSA Archives have a typescript copy of “Assos Days,” the diary that architect Francis Bacon kept during the excavation. In 1996, as the newly hired Archivist of the American School, I met one of Bacon’s nieces (Helen Bacon Landry) who was visiting the School. She left me with a copy of his Assos Days, a collection of letters and journals that he himself transcribed at some later point in his life “for the Benefit of Family and Friends, But Interesting Chiefly to Himself.” (See also Congdon 1974).

Bacon’s entry for May 16, 1881 (the day that Schliemann visited Assos) reads as follows:

In the evening, after finishing our frugal meal, a string of horses led by two Zaptiehs with long guns were seen coming down from the Acropolis, followed by an old fellow in a white helmet. I went up and spoke to him; found it was Dr. Schliemann making a tour of the Troad and the trying to locate the cities of Homer! Eliot took him to our bathing place and afterwards he spent the evening with us. He wouldn’t talk about anything but prehistoric remains and cared nothing for our work here. He had a stunning coin of Assos of which I made a sketch. He told us about his lawsuit with the Turkish government. He is a knowing old chap, but I think a bit cracked! He seems much older than when I met him at Hissarlik at 1879. He thinks this must be ancient “Chrysa”!

Works Cited

Allen, S.H. (ed.) 2002. Excavating our Past: Perspectives on the History of the Archaeological Institute of America, Boston.

Congdon, L. 1974. “The Archaeology Journals of Francis H. Bacon,” Archaeology 27, 1974: 83-95

Ousterhout, R. G. 2011. John Henry Haynes: A Photographer and Archaeologist in the Ottoman Empire 1881-1900, Istanbul.

Bravo Curtis. Thanks for sharing this one with us. As usual you in your wanderings have discovered treasures.

Splendid. A great read. Thanks for your diligence in finding the diary.

Enjoyed it immensely. Thanks for posting it.

Wonderful stuff, Curtis, though I am saddened by a life lived so briefly. I will remember the story whenever I take folks to see Schliemann’s temple tomb in the First Cemetery.

[…] Genius] and have hosted two posts by Curtis Runnels [Who Went to Schliemann’s Wedding? and, “All Americans Must Be Trojans at Heart”: A Volunteer at Assos in 1881 Meets Heinrich Schliemann], the author of The Archaeology of Heinrich Schliemann: An Annotated Bibliographic Handlist […]

[…] at Assos when the latter came to see their excavation. (About Bradley and Schliemann, read “All Americans Must Be Trojans at Heart”: A Volunteer at Assos in 1881 Meets Heinrich Schlieman….) Schliemann must have extended an invitation to Bradley to visit him at home when he came to […]