The Charioteer of Delphi in the Clutches of WW II

Posted: March 16, 2022 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Classics, History of Archaeology, Modern Greek History | Tags: Alexandros Kontoleon, Antonios Keramopoulos, Delphi Charioteer, Hans von Schoenebeck, Ηνίοχος των Δελφών, Vasileios Petrakos, Wilhelm Kraiker 7 CommentsBY ALEXANDRA KANKELEIT

Alexandra Kankeleit, an archaeologist who specializes in the study of Roman mosaics, has also been part of an extensive project of the German Archaeological Institute (Athens and Berlin), titled The History of the German Archaeological Institute at Athens during the National Socialist Era. As part of the project, she has examined a host of bibliographic and archival sources in both countries that document activities of German archaeologists in Greece from 1933 until 1944. Here she contributes an essay about the adventures of the Delphi Charioteer during the German Occupation in Greece.

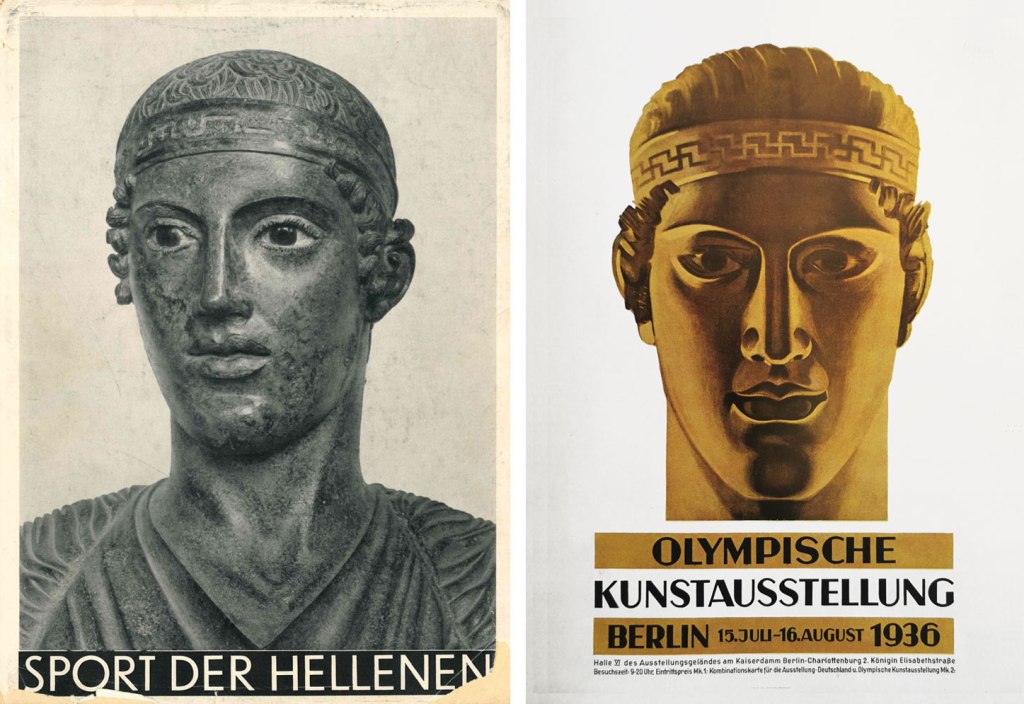

The Charioteer of Delphi (Ο Ηνίοχος των Δελφών) is one of the best-preserved and most important bronze statues of ancient Greece. Since its discovery in 1896, it has been one of the main attractions of the Archaeological Museum in Delphi. As a symbol of ancient civilization and the eventful history of Greece, it is still a frequently recurring motif in the visual and performing arts (Figs. 1-2).

During the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, the Charioteer was promoted together with the Discobolus of Myron and the Boxer of the Quirinal as the prototype of the Greek athlete in antiquity (see Olympia Zeitung 3, July 23, 1936, p. 46). Thus, his face adorned the covers of catalogs and propaganda material circulated in 1936 on the occasion of the Olympiad (Figs. 3-4).

German scholars also increasingly turned their focus on the Early Classical masterpiece. In his Habilitation “Der Wagenlenker von Delphi” (The Charioteer of Delphi), the archaeologist Roland Hampe (1908-1981) pursued his goal of reducing the many “ambiguities, misunderstandings, differences of opinion” concerning the monumental bronze group. His manuscript was completed in August 1939 and published as a monograph in 1941 (Hampe 1941).

Read the rest of this entry »The Cretan Idyll of Harriet Boyd and Charles Henry Hawes

Posted: February 12, 2022 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Art History, Biography, Classics, Crete, Greek Folklore, History of Archaeology, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism, Women's Studies | Tags: Charles Henry Hawes, Crete, Harriet Ann Boyd 6 CommentsBY CURTIS RUNNELS – PRISCILLA MURRAY

Curtis Runnels, Professor of Archaeology at Boston University and an expert in Palaeolithic archaeology in Greece, and his wife Priscilla Murray, an anthropologist and Classical archaeologist, here contribute to From the Archivist’s Notebook a story about their purchase of a sketchbook from the early 20th century with watercolors depicting places and people on Crete.

We visited an antiquarian bookfair in Concord, New Hampshire, about twelve years ago and a booth belonging to a dealer from Vermont, who specialized in original artwork, caught our eye. Sorting through piles of miscellaneous materials, we found a few things relating to Greece, and a small (8 by 4 inches; 20 x 10 cm) artist’s sketchbook grabbed our attention. It was displayed on a table opened to a watercolor view that seemed familiar. Surely it was the entrance to the harbor at Herakleion on Crete! And indeed, penciled in one corner was the inscription “Candia,” the older name for the city which both confirmed the identification and provided a clue that the sketchbook, as dealers in antiques like to say, “had some age.” There were other artworks in the sketchbook that are dated to April 1905, and still others with various dates in 1915, and one dated to 1916. The artwork from 1905 was the most interesting for us. Turning the pages of the sketchbook we saw line drawings of dancers at Knossos and a man drawing water from a well in Siteia, pastels of houses labeled Knossos and “Sitia, as well as watercolors and line drawings of Mykonos, Ios, and other Cycladic islands, Sounion, and Athens. The unknown artist was interested particularly in the new Minoan finds from Knossos as is evident from the line drawings of wall paintings and artifacts in the “Candia Museum.”

Although there is no artist’s signature, we guessed that the artist must be someone interesting, perhaps even someone we would recognize. After all, how many Americans or British travelers (the fact that the titles are in English is the reason for assuming the nationality of the artist) were sufficiently interested in Knossos and the Minoans to visit Crete in 1905 at a time when there was much unrest on the island? We bought the sketchbook and took it home to do more research.

The Artemision Shipwreck: Sinking Into the ASCSA Archives

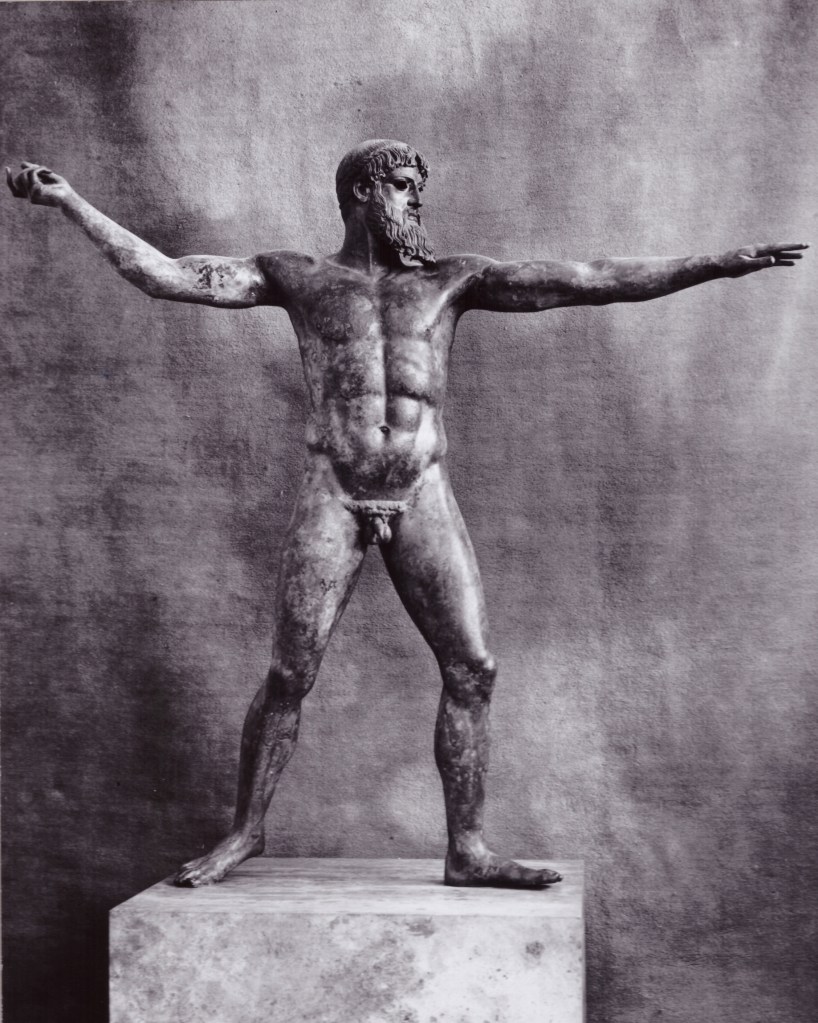

Posted: October 10, 2021 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Classics, History of Archaeology, Philhellenism | Tags: Artemision Jockey and Horse, Artemision Shipwreck, Artemision Zeus, Charles H. Morgan, George Hasslacher, George Mylonas, Georgios P. Oikonomos, Γεώργιος Οικονόμος, Philip R. Allen, Sean Hemingway 7 CommentsIn late 1928 the Greek and the international press published several articles and photos of a sensational archaeological discovery: a large bronze male statue found near Cape Artemision, in the north of Euboea. On central display at the Archaeological Museum in Athens since 1930, the statue is known to the public as the Aremision Zeus (or Poseidon).

Two years before, in the same area, fishermen had caught in their nets the left arm of a bronze statue that was also transferred to the National Museum in Athens. That discovery did not, however, provoke any further archaeological exploration in the area, most likely for fiscal reasons. But then in September 1928, the local authorities in Istiaia, a town in northern Euboea, were informed of illicit activity in the sea near Artemision. Acting fast, they sailed to the spot and caught a fisherman’s boat filled with diving equipment. Not only that, its crew had already pulled out the right arm of a bronze statue. A few days later the authorities were able to bring up from the bottom of the sea a nearly complete male, larger than life, statue. The first photos showed the armless statue laying on its back on a layer of hay (Note how the area of the genitals has been conveniently darkened in the newspaper photos so that the public would not be offended by the nudity of the statue.)

Read the rest of this entry »GREEKS THEY ARE CALLED THOSE WHO SHARE IN OUR EDUCATION

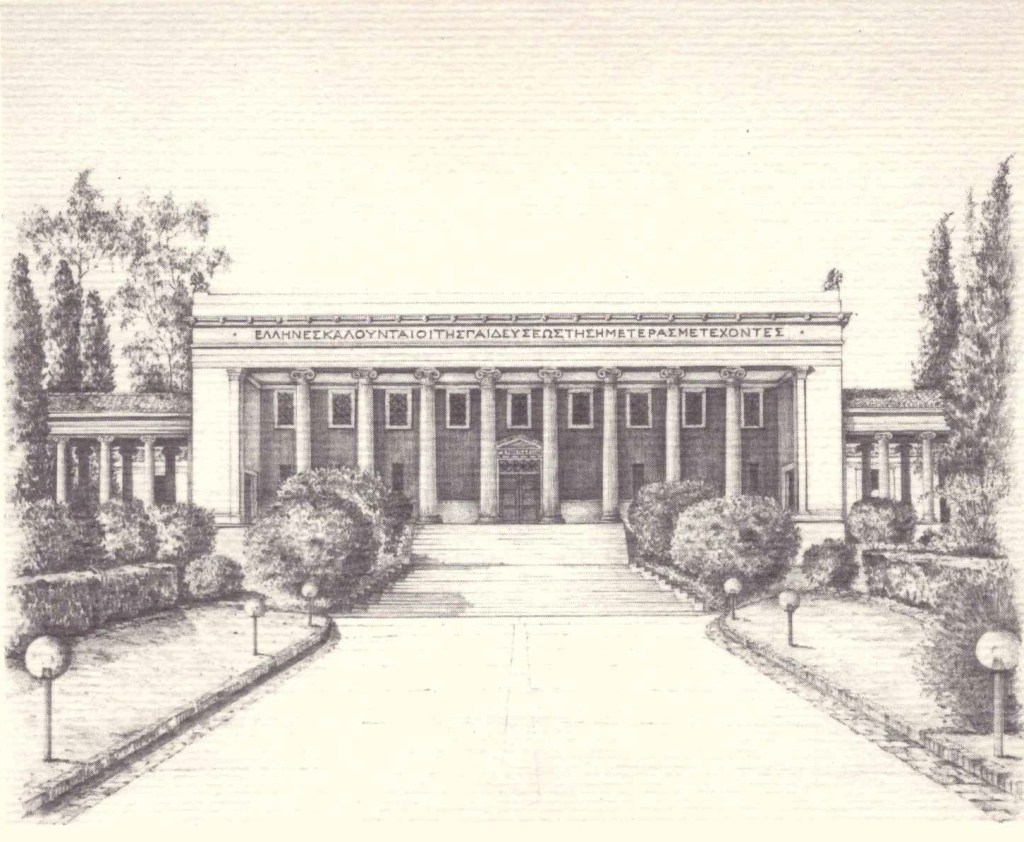

Posted: May 27, 2021 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Classics, History of Archaeology, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism | Tags: Edward Capps, Edward D. Perry, Gennadius Library, Kostas Varnalis, Paul E. More, Paul Shorey 10 CommentsAmong the first things one notices when approaching the Gennadius Library is the large inscription on the architrave of the neoclassical building, built by the American School of Classical Studies (ASCSA or the School hereafter) in 1926 to house the personal library of John Gennadius. It reads: ΕΛΛΗΝΕΣ ΚΑΛΟΥΝΤΑΙ ΟΙ ΤΗΣ ΠΑΙΔΕΥΣΕΩΣ ΤΗΣ ΗΜΕΤΕΡΑΣ ΜΕΤΕΧΟΝΤΕΣ, that is, GREEKS THEY ARE CALLED THOSE WHO SHARE IN OUR EDUCATION. It is a line taken from Isocrates, Panegyricus 50.

In the School’s Archives there is extensive correspondence between the Chair, Edward Capps, and the Secretary of the Managing Committee, Edward D. Perry, concerning this choice of passage. Both men were distinguished classicists: Capps (1866-1950) was a professor of Classics at Princeton and one of the three original editors of the Loeb Classical Library, and Perry (1854-1938) taught Greek and Sanskrit at Columbia University for several decades.

The original guidelines from the architects of the building, John Van Pelt and W. Stuart Thompson, limited the length of the inscription to twenty letters; in addition, the architects insisted on placing two rosettes to the left and right of the inscription.

The discussions about the inscription began in late 1922, as soon as the School had secured funding from the Carnegie Corporation for the construction of the library. “The book plate of [John] Gennadius contains: ΚΤΑΣΘΕ ΒΙΒΛΙΑ ΨΥΧΗΣ ΦΑΡΜΑΚΑ [buy these books, which are the medicine of the soul]. I think you could get up something better for the frieze over the entrance” Capps teased Perry on October 29, 1922. [1]. To which Perry answered: “I have been thinking over the matter a good deal, but so far have hit upon nothing that pleases me. As he [John Van Pelt] says ‘an inscription some twenty letters long’ I feel a good deal crammed. I will send him, as a mere suggestion to work with, the following, taken with slight changes from Aeschylus’s Prometheus, line 460: ΣΥΝΘΕΣΕΙΣ ΓΡΑΜΜΑΤΩΝ ΜΝΗΜΗ ΑΠΑΝΤΩΝ [“the combinations of letters, memory of all things”] which is thirty letters long” (AdmRec 311/3, folder 5, November 3, 1922).

Read the rest of this entry »The Transatlantic Voyage of a Greek Maiden

Posted: April 17, 2021 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Classics, History of Archaeology, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism, Women's Studies | Tags: Acropolis Kore 675, Gisela M. Richter, Greek Pavilion World Fair 1939, Henry Morgenthau, Hermes of Praxiteles, Spyridon Marinatos 7 CommentsOn March 31, 1947, Gisela Richter, Curator of Greek and Roman Art at the Metropolitan Museum of New York, sent a confidential letter to Carl W. Blegen, Professor of Classics at the University of Cincinnati and a distinguished archaeologist. Richter approached Blegen not only because they were friends but because, by having lived in Greece for many years, Blegen had formed strong connections with the local community at all levels. In addition, during World War II, Blegen had offered his services to the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and, upon his return to Greece, he had served as Cultural Attaché at the U.S. Embassy (1945-1946). Richter was writing Blegen about five pieces of Greek sculpture on loan to the Metropolitan Museum, including Kore 675 from the Acropolis. Richter refers to her as the “Maiden”.

“As I think I told you, we are naturally anxious to return to the Greeks what they have kindly lent us but very much hope that some arrangement can be made by which we may retain that one Maiden. The other pieces we are not even going to ask for, as there are obvious reasons in each case why the Greeks would not want to part with them, and asking for them would only weaken our case for the Maiden. The latter is one of many, and would hardly be missed in Athens, whereas here she would act as an ambassadress of goodwill, etc., etc.”

Richter sought Blegen’s advice about how to proceed with the request. “The loan to Greece ought to create goodwill for America, but naturally we don’t want to seem to cash in on it.” Richter was referring to President Truman’s announcement of March 1947, known as the Truman Doctrine, whereby the U.S. government granted $300 million in military and economic aid to Greece and $100 million to Turkey. “Would it be better to ask for the piece as a gift and perhaps compensate for it in some other way, or would a direct purchase be better? You who have been in Greece recently and know Greek politics will be able to advise us better than anyone else,” concluded Richter.

Blegen’s response exists only as a draft in his personal papers at the Archives of the American School of Classical Studies (ASCSA or School hereafter). The mention of [Spyros] Skouras’s name in his response (not mentioned in Richter’s letter) suggests that Richter might have followed up with a second letter or a telegram or a note to Blegen’s wife, Elizabeth. To Richter’s disappointment, Blegen could not think “of any altogether satisfactory way of approach to recommend” (ASCSA Archives, Carl W. Blegen Papers, Box 13, folder 1, April 6, 1947). However, he did not reject the idea of having Spyros Skouras, the Greek-American movie mogul, mediate with the Greek authorities “since he has much influence and could apply some pressure. If he could propose it in the right quarters as an idea of his own, not inspired by you, there might be some hope that he could persuade them to make the offer as a spontaneous gesture of friendship.” Blegen thought of another alternative as well: “to ask Bert [Hodge] Hill to try his powers of persuasion.” Hill, Director of the American School from 1906 until 1926, was still considered to be social capital by many at the School. A gifted individual with access to the upper echelons of a small Athenian society, including the royal family, Hill “had his way with men” and could influence politicians. Blegen thought that it would have to be a political decision since the Archaeological Service would likely oppose to it.

There is no other correspondence between Blegen and Richter on this matter. We know that the Acropolis Maiden and the other pieces of sculpture were returned to Greece, so one assumes that either Richter did not press the issue further or that the mediators were unsuccessful. However, it is interesting to read an announcement in the Greek newspaper ΕΛΕΥΘΕΡΙΑ on August 11, 1948, titled “The Greek State will Sell Certain Antiquities. Superfluous in Museums,” which implies that the Ministry of Education might have considered briefly the idea of selling duplicate antiquities, in order to finance the reopening of Greek museums and the beautification of those archaeological sites that had suffered much during the War.

Read the rest of this entry »