Sophia and Heinrich Schliemann: An Unusual Relationship (Pt. II)

Posted: December 26, 2025 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Exhibits, History of Archaeology, Modern Greek History, Women's Studies | Tags: family-history, genealogy, Heinrich Schliemann, History, Αγαμέμνων Σλήμαν, Ανδρομάχη Σλήμαν, Ερρίκος Σλήμαν, Σοφία Σλήμαν, Sophia Schliemann, travel 2 CommentsHappy Holidays! Inspired by the correspondence between Sophia and Heinrich Schliemann, Natalia Vogeikoff-Brogan and Leda Costaki curated, in the spring of 2025, a bilingual digital exhibition titled Sophia and Heinrich Schliemann: An Unusual Relationship (Σοφία και Ερρίκος Σλήμαν: Μια ασυνήθιστη σχέση), a version of which is presented here in two parts to reach a wider audience. Part I was published in this blog on December 6, 2025. We now continue with the second part of their captivating story.

Posted by Natalia Vogeikoff-Brogan and Leda Costaki, ca. 1,800 words, 10′ read time.

Recap (or Go to Part I)

Heinrich Schliemann came to Greece in 1869, having sold his businesses in Russia and divorced his Russian wife. Schliemann was looking for a new partner to share his dream of excavating the Homeric citadels of Troy and Mycenae, so as to prove that the Iliad was not a fairy-tale. In September 1869 Heinrich married Sophia Engastromenou. He was then 48 years old, and she was 18. Following an unsuccessful honeymoon, in the course of which the couple were on the verge of divorce, Schliemann left for Troy to start excavating. The couple did not separate, and in fact they became famous for their discoveries, remaining together till Heinrich’s death in 1890. In 1936 their children, Andromache and Agamemnon, donated their Papers to the American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

Married to a Sociopath

After their successful appearance in London, the Schliemanns left for their beloved Boulogne-sur-Mer, where they stayed for five weeks at the Hotel du Pavillon. From there, instead of returning to Greece, Schliemann established the pregnant Sophia in Paris, under the superintendence of French and Greek physicians, in order to forestall yet another miscarriage after the many she had undergone after the birth of Andromache. For the following months, up until the birth of Agamemnon in March 1878, Sophia remained alone in Paris with Andromache and their French nanny, with occasional visits from her brother Spyros and, towards the end of her pregnancy, from her mother. Heinrich paid them only one two-day visit on his way from Würzburg to Athens. He returned to Paris a week before his son’s birth on the 16th March 1878.

“Πώς λέγεις ότι δεν θα είσαι δια τα Χριστούγεννα μαζύ μας, είναι δυνατόν να μείνης περισσότερον των 6 ημερών εις Würzburg;”

“How can you say that you will not be with us for Christmas? Is it possible to stay longer than 6 days in Würzburg?” Sophia wrote him on December 11, 1877.

Photo: Sophia, pregnant with Agamemnon, with little Andromache in Paris, 1877. ASCSA Archives, Lynn and Gray Poole Papers.

David Traill considers that only a sociopath and egoist like Schliemann could leave his wife alone in a foreign country throughout her pregnancy (Traill 1986). Even Lynn and Gray Poole, authors of One Passion, Two Loves, who painted a very romantic picture of the relationship between Heinrich and Sophia, find Schliemann’s behavior inexplicable.

Sophia Reaches Her Limits!

Aside from Heinrich’s miserliness, another thorn in their relationship was his insistence on the curative properties of water, whether spas, cold baths or sea-bathing. He himself swam winter and summer. When in Athens he would go every morning on horseback down to Faliron. Even at Troy he never missed the chance of riding to the sea to bathe.

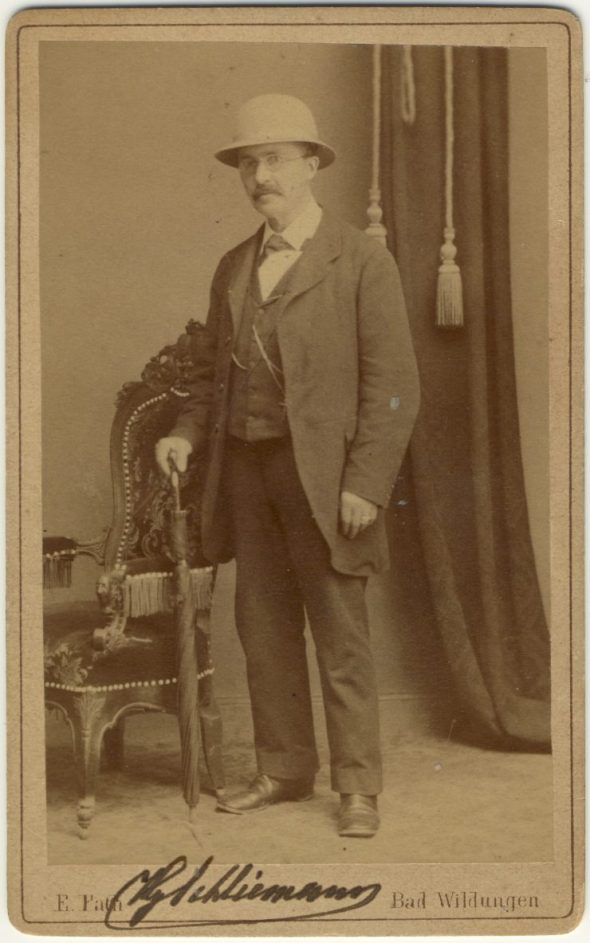

From 1880 the almost obligatory holidays would begin for Sophia and the children at some European spa in Germany or Austria. Schliemann was usually absent or would take the waters at some other nearby spa, as in the summer of 1883 when he was at Bad Wildungen in Germany while Sophia and the children went to Carlsbad and Franzenbad in Bohemia.

On August 22, 1883, Sophia wrote him from Franzenbad: ‘I have had enough of the baths…’ (‘Απηύδησα πλέον των λουτρών‘). Before that, she thanked him for the photograph he sent from Bad Wildungen, commenting humorously: ‘Your photograph […] is most expressive; I read my whole little Heinrich in it (‘αναγιγνώσκω μέσα εκεί όλον μου τον Ερρικάκη‘). Surely you thought of me at that very moment, for whenever you speak to me you wear that very expression.’ ASCSA Archives, Heinrich Schliemann Papers, Box 92, #703.

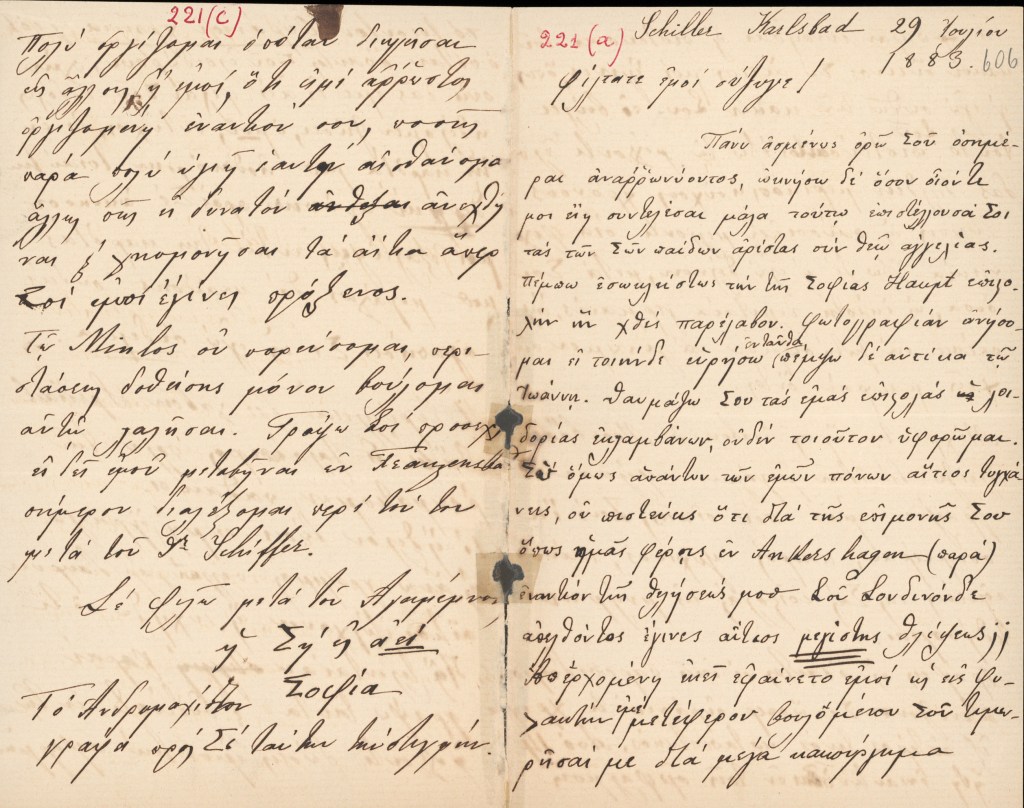

On July 29, 1883, with relations already strained after Schliemann had compelled Sophia and the children to spend several weeks with his family at Ankershagen, Sophia wrote to him from Carlsbad that the only way they could still find happiness was to live apart: ‘we must seek to be happy while living at a distance’ (‘πρέπει να ζητήσωμεν να γίνωμεν ευτυχείς μακράν όντες‘). And if she were ever to cease loving him, ‘you will weep greatly; no one will ever love you as I do -no one’ (‘μεγάλως θα κλαύσης, ουδείς αγαπήσει Σε ως εγώ ουδεμιά‘). She was also angered by Heinrich’s claims to others that she is supposedly ill.

On the contrary, she felt she was in excellent health, too healthy, in fact, to keep tolerating and forgiving him:‘I feel myself far too healthy; otherwise, how could I endure and forget the causes for which you became the source of my sufferings?’

ASCSA Archives, Heinrich Schliemann Papers, Box 92, #606.

Sophia’s most significant revolt happened at the end of 1885, when Schliemann was on holiday in Cuba, and she took it upon herself to make the important decision to cut short Andromache’s studies at a Lausanne school for girls and return to Athens. Sophia disagreed with the progressive principles of the school. Deep down, it is possible that she could not stand the idea of yet another ‘banishment’ from her beloved Athens.

One year later, at the end of summer 1886, having once more endured a ‘banishment’ to European watering places far from the sea she adored, she decided, without his approval, to take the children and go to Ostend on the Belgian coast.

“My dear papa”

With Schliemann absent for long periods, Sophia had the primary role in the upbringing and supervision of their children. In the Heinrich Schliemann archive there are more letters from Andromache, who was the eldest, and fewer from the younger Agamemnon. Sophia always gave Heinrich news of the children, and sometimes made them add one or two lines to her own letters.

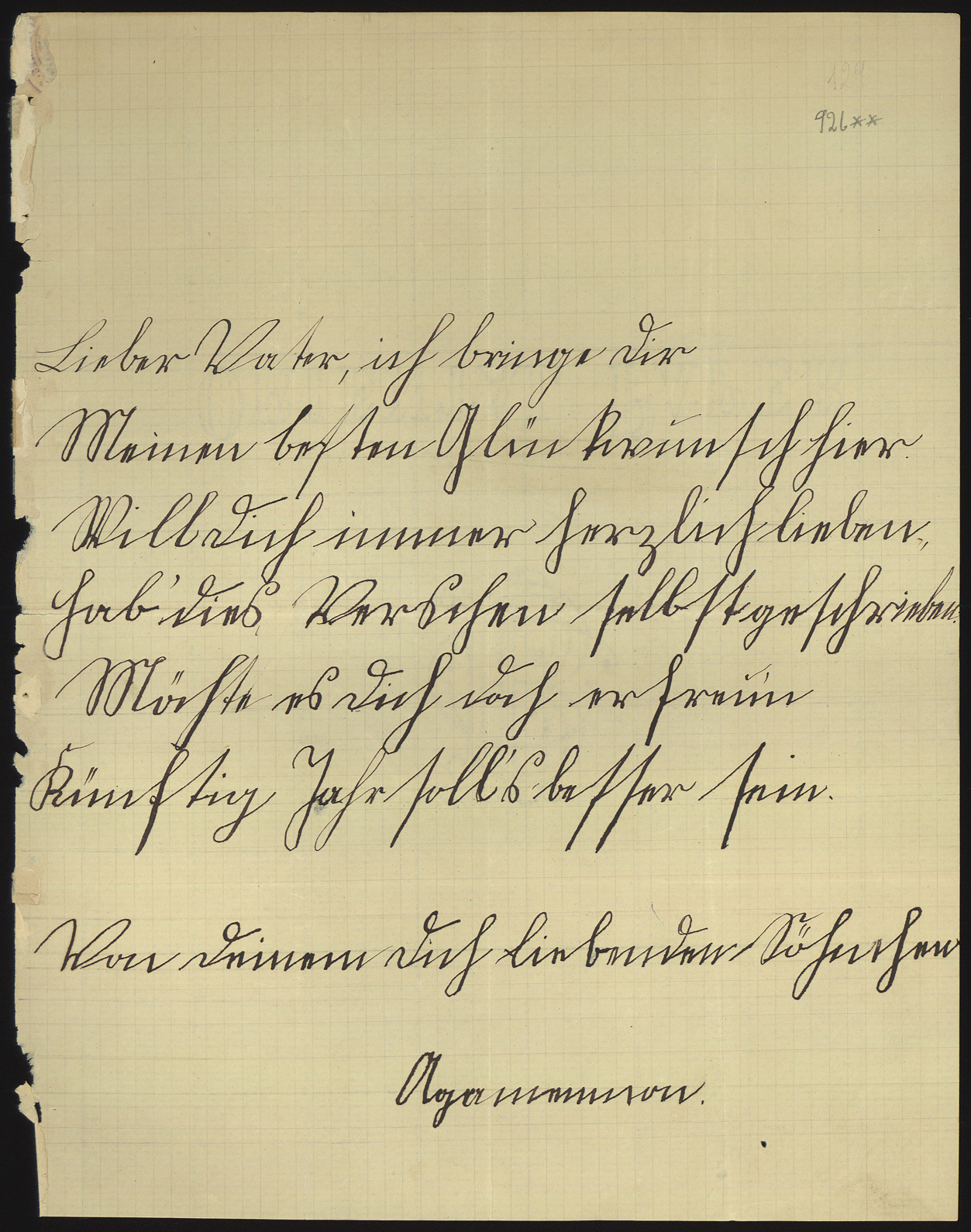

At the beginning of 1886, with his mother’s help, seven-year old Agamemnon (known as ‘papa’s child’ for he had taken after his father’s character), thanked his father, who was away on a trip to Cuba, for the rare stamps he sent, and expressed his regret that he was not yet old enough to travel with him. In the same envelope, Sophia enclosed another letter from little Memekos (his nickname) written in German so that Heinrich could witness his son’s progress.

Agamemnon and Andromache, ca. 1883. Agamemnon’s German letter to his father, 1886 (ASCSA Archives, Heinrch Schliemann Papers, Box 97, #926d).

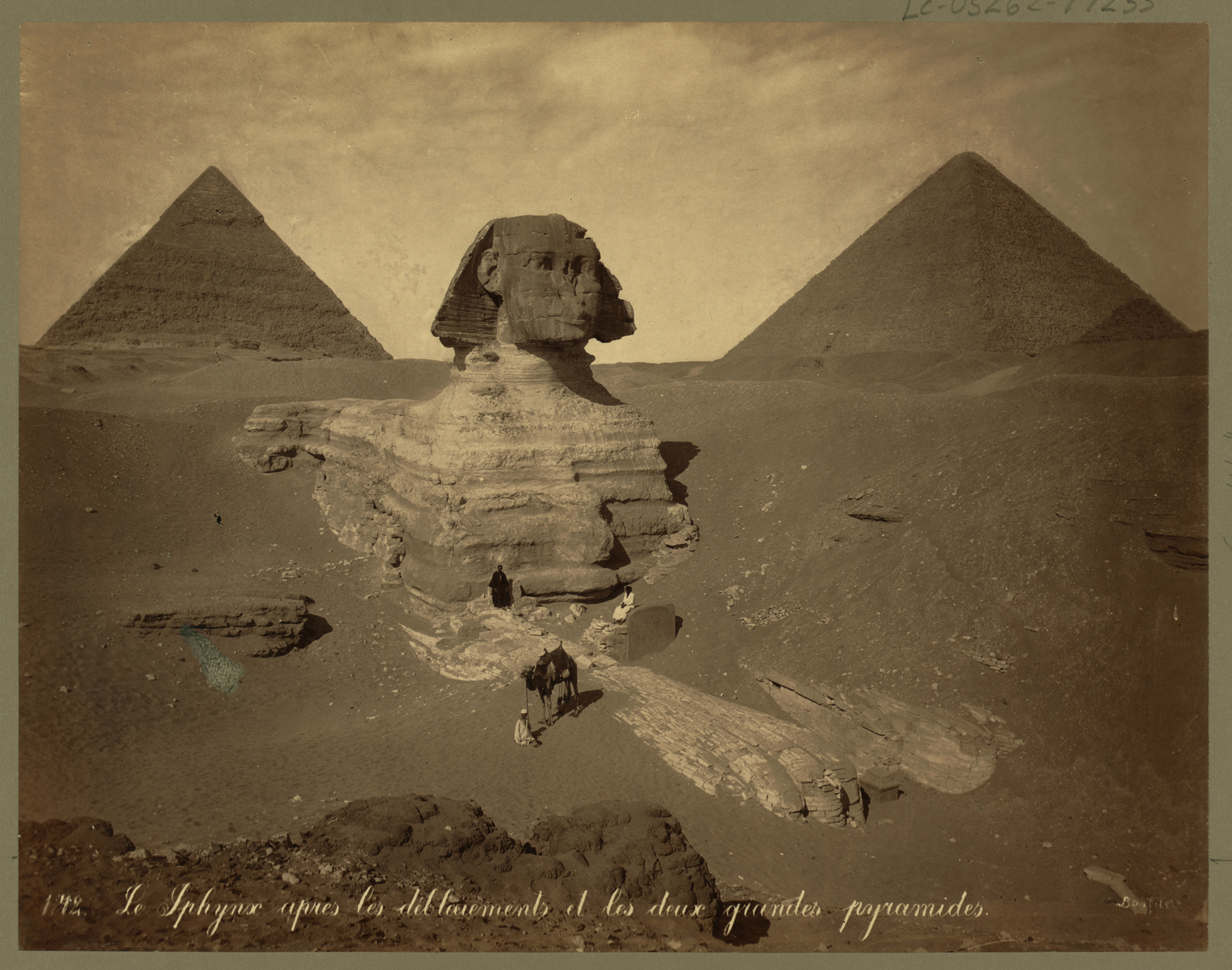

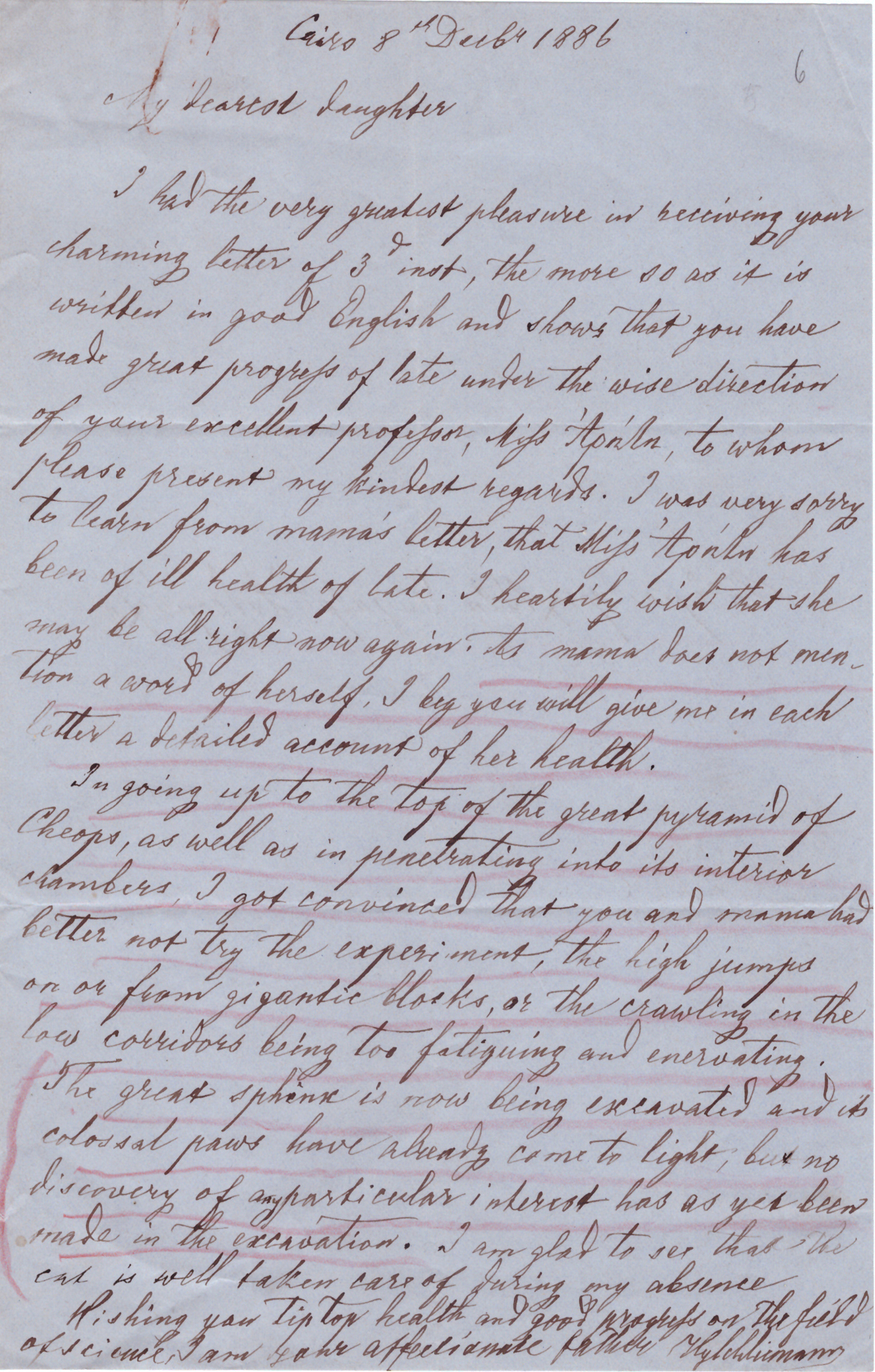

On December 8, 1886, writing from Cairo, Schliemann praised his daughter Andromache for her good English: ‘I had the very greatest pleasure in receiving your charming letter […], the more so as it is written in good English and shows that you have made great progress […]. In the same letter he informed her of the excavation of the Great Sphinx at Giza: The great sphinx is now being excavated, and its colored paws have already come to light […].’

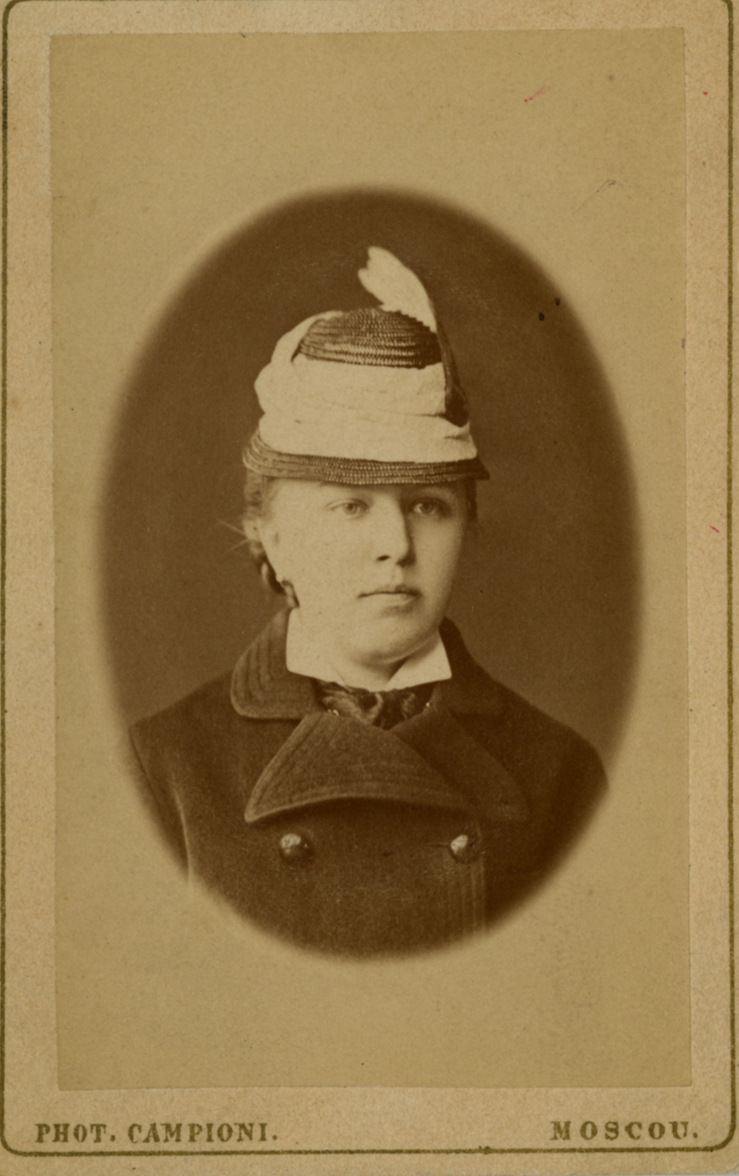

Andromache Schliemann, 1888; Schliemann witnessed the excavation of the Great Sphinx (Source: Bonfils Wikipedia Commons); Schliemann to his daughter, Dec. 8, 1886. ASCSA Archives, Heinrich Schliemann Papers

Schliemann also had three children from his first marriage with the Russian Ekaterina Lyschina: Sergei (1855-1939), Natalya (1858-1869) and Nadezhda (1861-1935). Schliemann was on his honeymoon with Sophia when he heard of the death of his daughter Natalya. In a letter to her father Sophia described that painful time: when the news arrived, ‘for three days he resembled a dead man’.

In the Heinrich Schliemann archive there are about 115 letters from Nadezhda and 411 from Sergei, which prove that Schliemann maintained close contact with the children of his first marriage. Since most of them, with very few exceptions, are written in Russian, we cannot reach a clear understanding of the relations between them. But it seems that Sophia had a good relationship with Heinrich’s children, at any rate with Sergei.

Sergei Schliemann, 1872; Nadezhda Schliemann, 1870s. Source: ASCSA Archives, Melas Family Papers.

“What God Has Joined Together”

The construction of the Iliou Melathron mansion took three years (1878-1880). It was Heinrich’s life’s dream, but not Sophia’s, who was emotionally attached to their first house in Mouson Street (Οδός Μουσών). The size and magnificence of the new house reminded her more of a museum than a home.

In an undated letter, likely written in 1879, while theIliou Melathron was still under construction, Heinrich wished that he and Sophia would celebrate there their silver and gold wedding anniversaries, ‘but also the weddings of our children, in health, in harmony, and in happiness’ (‘αλλά και τους των ημετέρων παίδων γάμους, υγιαίνοντες, ομοφρονούντες τε και ευδαίμονες’) [ASCSA Archives, Sophia Schliemann Papers #130].

On September 21, 1890, Schliemann celebrated their 21st wedding anniversary in Athens without Sophia and the children, whom he had sent to an Austrian spa. Alone and lost in thought, he reviewed the two decades of their married life, concluding that Sophia had been a beloved companion and partner, and a worthy mother:

‘[…] I see that the Fates have healed many of our wounds, but have also bestowed on us many joys; and as we tend to see the past through rose-colored spectacles, forgetting its sufferings and recalling only its moments of joy, I cannot praise our marriage sufficiently. For you have never ceased to be for me my beloved wife (άλοχος προσφιλής), a pure-minded companion (εταίρος αγαθός) and trustworthy guide in difficulties (κυβερνήτης εν ταις δυσκολίαις πιστός), as well as a gentle fellow-traveller and remarkable mother (συνέμπορος φιλόφρων και μήτηρ των ου τυχουσών)’ (ASCSA Archives, Heinrich Schliemann Papers, Copybook 43, 20).

Schliemann died of postoperative complications at Christmas in 1890 at Naples, on his way back to Greece. Only shortly before, he had sent two telegrams to Sophia, asking them to wait for him for the Holidays: ‘Come state? Arriverò sabbato mattina.’

After Heinrich’s death, Sophia lived in the Iliou Melathron until 1926, when she moved to Palaio Faliro. The Iliou Melathron was for many years a social and intellectual landmark of Athens, where Sophia and her daughter Andromache presided hospitably over Schliemann’s posthumous fame.

Sophia Schliemann, ca. 1880s, and at an older age.

References

Poole L. and G. 1967. One Passion, Two Loves: The Schliemanns of Troy, London.

Trail, D. A. 1986. “Schliemann’s Acquisition of the Helios Metope and his Psychopathic Tendencies,” Myth, Scandal, and History: The Heinrich Schliemann Controversy and a First Edition of the Mycenaean Diary, ed. W. M. Calder III and D. A. Traill, Detroit, 48-80.

The Forgotten Olympic Exhibition: Georg Alexander Mathéy’s Contribution to the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin.

Posted: August 2, 2022 Filed under: Archival Research, Art History, Biography, Exhibits, History of Archaeology, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism | Tags: Georg Alexander Mathéy, Polyxene Roussopoulos Mathéy, Walter Hege 3 CommentsBY ALEXANDRA KANKELEIT

Alexandra Kankeleit is a German-Greek archaeologist and historian. She has been researching German archaeology in Greece during the Nazi period for several years. Since July 2021 she has been working for the CeMoG (Centrum Modernes Griechenland) at the Freie Universität Berlin, where she will teach a seminar on the 1936 Summer Olympics in the upcoming winter semester. Here she contributes an essay about the German artist Georg Alexander Mathéy (1884-1968), who lived in Greece in the 1930s and whose work was displayed in the Summer Olympics of 1936.

The Badische Landesbibliothek in Karlsruhe (BLB) has held a large part of the estate of painter and writer Georg Alexander Mathéy (1884-1968) since 1993. In 2017, the BLB organized an exhibition, titled Sprachbilder – Bildersprache: Die Künstler Helene Marcarover und Georg Alexander Mathéy, to showcase the works of Mathéy together with those of another artist, the painter and poet Helene Markarova (1904-1992). Both artists, whose work was shaped by the two wars, by migration and alienation, were able through literature to transform images into words, and vice versa. A wonderful accompanying publication provides insights into Mathéy’s life and creative work (Axtmann – Stello 2017).

Trained as an architect in Budapest, Mathéy made his name as an illustrator of numerous books and magazines, achieving commercial success already at a young age. He also designed stamps, textiles, and a Rosenthal coffee service. Two of his stamp designs are still remembered today because of their intense colors and memorable motifs: the “bricklayer” (1919) and the “post horn” (1951). They can be described as classics of German stamp design.

In addition to this modern, highly reductivist formal language, Mathéy also mastered other, more traditional media, primarily in his large-scale watercolors and oil paintings.

I became interested in Mathéy’s largely forgotten contribution to the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin. The starting point is material from the archives of the BLB, which provided new and important information about Mathéy. (I would like to thank the director of the BLB, Julia Hiller von Gaertringen, for her interest and active support in my project. A detailed German version of this article can be found on the BLBlog.) Further information can also be found in an unpublished research paper on Georg Alexander Mathéy, which the designer Ulrike Jänichen completed in 2003 under the direction of Professor Mechthild Lobisch at the Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule in Halle. She kindly made her work available to me.

The Spirit of St. Louis Lives in Athens, Greece

Posted: February 2, 2017 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Exhibits, Greek Folk Art, History of Archaeology, Philhellenism | Tags: Betty Grossman, George Mylonas, Lucia O' Reilly, Martyl Langsdorf, Spirit of St. Louis, Wallace Herndon Smith 3 CommentsHave you noticed that in the last ten days the press has been flooded with articles about the Doomsday Clock? Here are some of the titles: “The Doomsday Clock is the closest to midnight since 1953” (Engadget, Jan. 28, 2017), “Nuclear ‘Doomsday Clock’ ticks closest to midnight in 64 years (Reuters), “Doomsday Clock Moves Closer to Midnight, Signaling Concern Among Scientists (The New York Times, Jan. 26, 2017), and “The Doomsday Clock is now 2.5 minutes to midnight, but what does that really mean? (Science Alert).

Martyl’s design of the Doomsday Clock for the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists

The Doomsday Clock was created in 1947 by members of The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’s Science and Security Board; several of them were part of the “The Manhattan Project” that led to the creation of the first atomic bomb. (For those of you who want to learn more about “The Manhattan Project,” I recommend a drama series that premiered in 2014; although the series was discontinued after the second season, it featured good acting and it was fun to watch. Also see Jack Davis’s Communism In and Out of Fashion, Sept. 1, 2016.) “Originally the Clock, which hangs on a wall in The Bulletin’s office at the University of Chicago, represented an analogy for the threat of global nuclear war; however, since 2007 it has also reflected climate change and new developments in the life sciences and technology that could inflict irrevocable harm to humanity… The Clock’s original setting in 1947 was seven minutes to midnight. It has been set backward and forward 22 times since then, the smallest ever number of minutes to midnight being two in 1953, and the largest seventeen in 1991” (after Wikipedia, accessed 28/1/2017). As of January 2017 (and this explains the flurry of articles in the press), the Clock has been set at two and a half minutes to midnight, a reflection of President Trump’s comments about nuclear weapons: “The United States must greatly strengthen and expand its nuclear capability until such time as the world comes to its senses regarding nukes.” Trump posted this remark on Twitter on December 22, 2016, and followed it with an even more worrisome comment: “Let it be an arms race,” he said, referring to the Russians.

While reading the history of the Doomsday Clock my eyes happened to fall on the cover of the 1947 Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, which featured for the first time the Clock (at seven minutes to midnight), and the name of the artist who had designed it: Martyl Langsdorf. Martyl is an unusual name, and I had seen it before. I went to the Archives Room of the American School of Classical Studies (ASCSA or the School hereafter), where we keep the School’s administrative records, and personal papers of its members. There, hanging on one of the walls, was an abstract painting depicting a mountainous landscape, and signed in the bottom left corner: “Martyl.” To my surprise, when I checked our inventory, there was a second work of art, an etching, by “Martyl” in the Archives of the ASCSA. But this one also carried a personal dedication: “To George and Lela with affection and admiration, Martyl.” This meant that Martyl’s other painting had also originally belonged to George and Lela Mylonas. Read the rest of this entry »

Le Noir et le Bleu: An Exhibit about the Mediterranean in Marseilles

Posted: November 1, 2013 Filed under: Art History, Exhibits, History, Mediterranean Studies | Tags: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Cyprian Broodbank, Fernand Braudel, Gennadius Library, Le musée des Civilisations de l’ Europe et de la Méditerranée (MuCEM), Le Noir et le Bleu, Marseilles, Mediterranean, Middle Sea, Nicholas Purcell, Odysseus Elytis, Peregrine Horden, Thierry Fabre 1 CommentFernand Braudel (1902-1985) declared “J’ ai passionément aimé la Méditerranée” in the preface of the first edition of La Méditerranée et le monde méditerranéen a l’ époque de Philippe II (1949). Archaeologists of my generation had to read or at least leaf through this three volume magnum opus written during Braudel’s captivity in concentration camps in Mainz and Lübeck during WWII (and delivered in lectures to fellow prisoners). “Had it not been for my imprisonment, I would surely have written a much different book…” wrote Braudel in his “Personal Testimony.” Much more about Braudel’s life and work can be found in the excellent biographical essay by historian William McNeill (Journal of Modern History 73:1, 2001, pp. 133-147); McNeill himself was awarded the National Humanities Medal by President Barack Obama on February 25, 2010.

Braudel belongs to the first generation of post war “savants” who tried to reconfigure the Mediterranean world after the destruction and the division that WWII brought to the shores of the “Middle Sea.” This new “mediterraneité” would be inclusive and post-colonial –at least in the erudite world of scholarship. Although Braudel’s approach has been criticized for overlooking certain fundamental conflicts (e.g., the clash of Islam and Christianity and the clash between Catholics and Protestants), it has cast a long shadow over subsequent study of the Mediterranean. More than three decades would separate Braudel’s last revision in 1966 (and translation into English in 1972) from the next major tome written about the Mediterranean by an ancient historian (Nicholas Purcell) and a medievalist (Peregrine Horden). Published in 2000, their study (The Corrupting Sea: A Study of Mediterranean History) is Braudelian both in size and depth and covers the period from about 800 B.C. through medieval times. While receiving both praise and criticism, Purcell and Horden’s book has rightly become a classic. Read the rest of this entry »

One Portrait, Three Institutions: Anders Zorn’s Portrait of William Amory Gardner

Posted: July 14, 2013 Filed under: Archaeology, Art History, Biography, Exhibits, History of Archaeology | Tags: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Anders Zorn, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, The Groton School, William Amory Gardner 4 CommentsFrom February 28 to May 13, 2013, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston hosted a large exhibit titled Anders Zorn: A European Artist Seduces America. The show re-evaluated the famous Swedish painter’s impact in the 1900s on America, where he was once held in high regard before being largely forgotten. The exhibit featured several international loans and was complemented by a series of lectures that experts on Zorn and his period presented.

Why am I writing about a retrospective on the activities of a Swedish painter in Boston? Because the American School of Classical Studies at Athens owns a portrait painted by Zorn—an image of William Amory Gardner (also known as WAG), the nephew of Zorn’s most important American patron and friend, Isabella Gardner. A balding WAG poses in three-quarter view while seated; he wears a black suit with an impressive red rose pinned on his left lapel. WAG himself never liked the portrait. Read the rest of this entry »