On the Trail of the “German Model”: ASCSA and DAI, 1881-1918

Posted: August 10, 2020 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, History of Archaeology, Women's Studies | Tags: Adolf Wilhelm, American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Eugene P. Andrews, Georg Karo, German Archaeological Institute Athens, Germanophilia, Nellie M. Reed, Ruth Emerson Fletcher, Theodore W. Heermance, Wilhelm Dörpfeld 13 CommentsFounded in 1881, the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (hereafter ASCSA or the School) was the third foreign archaeological school to be established in Greece and followed the French and German models. For the first thirty years, the activities of the American School were closely intertwined with those of the German Archaeological Institute at Athens (DAI or German Institute hereafter) and the Austrian Archaeological Institute of Athens (Austrian Institute or Station hereafter).

Eloquent testimony to their informal relationship is found in the ASCSA Annual Reports (AR) from 1887 onwards, where the directors of the American School repeatedly extended their profound gratitude to Wilhelm Dӧrpfeld, Director of the German Institute (1887-1912), Paul Wolters, Second Secretary of the German Institute (1887-1900), and Adolf Wilhelm, Secretary of the Austrian Institute (1898-1905), for allowing American students to attend their weekly seminars and archaeological excursions. Only occasionally, would the ASCSA similarly express its gratitude to a French or British colleague. In fact, the ASCSA relied so heavily on the German Institute that it delayed developing an independent academic program of its own until Dӧrpfeld stopped offering his lectures and tours in 1908.

In order to reconstruct the early decades of the School’s history and its relationship to the German Institute, in addition to the Annual Reports, I have also relied on a second type of primary source: personal correspondence and diaries. Both are rare, however. Unlike official documents that have a greater chance of survival (sometimes in more than one copy) the preservation of family correspondence is a matter of luck. Of the 200 men and women who attended the School’s academic program from 1881 to 1918, the outgoing letters of fewer than a dozen members have survived, and of those only the letters of few have found their way back to the School’s Archives.

By nature, each type of source provides the researcher with different kinds of information, even if both sources refer to the same people or events. Official reports are formal and, to a certain extent, sanitized documents that deliver the governing body’s mindset. I, personally, find private correspondence a more insightful source, although it can be subjective and overstated; nevertheless, it is the best thing that a historian has at his/her disposal for reconstructing the past because its testimonies offer contemporary perspectives. At a time when cell phones, text messages, and social media were not available, a letter was the only way for reporting one’s activities and also for expressing one’s feelings. Glimpses, for example, at the private correspondence of Nellie M. Reed, student of the School in 1895-1896, reveal a continuous stream of informal American-German gatherings during that year, otherwise undocumented in the Annual Reports.

In 2016, I was invited to participate in a conference that explored the early history of the German Archaeological Institute at Athens. I used that event as an opportunity to study and re-write the “German chapter” in the history of the American School.[1] The narrative explores the catalysts that brought these two groups together and asks: Was it simply the vibrant and charismatic personality of Dӧrpfeld, who for three decades dominated the archaeological community of Athens, that was responsible for the rapprochement of the two institutions in the closing decades of the 19th century, or did the School’s close ties with the German and Austrian institutes reflect a larger educational trend that prevailed in American academic circles in the second half of the 19th century?

Forgotten Friend of Skyros: Hazel Dorothy Hansen (Part I)

Posted: April 19, 2020 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Classics, Greek Folklore, History of Archaeology, Women's Studies | Tags: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, David M. Robinson, Dorothy Burr Thompson, George Mylonas, Hazel D. Hansen, Natalie Murray Gifford, Stanford University 12 Comments“Her main contribution was not destined to be in the field of excavation, but in discovering in dark cellars a good number of broken vases still covered with earth, discovered by others over the years in the island of Skyros. There she collected, cleaned, patched, and provided with a shelter transforming into a small Museum a room in the City Hall of Skyros. For this service to archaeology and the island she was made Honorary Citizen of Skyros,” wrote archaeologist George Mylonas about Hazel Hansen in early 1963, a few months after her death, in the Annual Report of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or the School hereafter).

I asked several archaeologists of my generation and slightly older if her name or her association with the island of Skyros rang a bell. It did not, although she was known well enough in Greece, for her death to be noted at length in Kathimerini (December 22, 1962), one of the most respected Greek newspapers. «Ηγγέλθη χθες στην Αθήνα ο θάνατος της φιλέλληνος αρχαιολόγου καθηγητρίας του Πανεπιστημίου Στάνφορδ, Χέιζελ Χάνσεν, η οποία είναι ιδιαιτέρως γνωστή δια το σύγγραμμά της περί του αρχαιοτέρου πολιτισμού της Θεσσαλίας…”. In addition to her work in Thessaly and Skyros, the note referred to her participation in the excavations at Olynthus and on the North Slope of the Acropolis. The author of Hansen’s Greek obituary knew her well and wanted to capture the accomplishments of a friend and able colleague. It must have been (again) George Mylonas, whose friendship with Hazel started in the 1920s when they were both at the American School.

Hazel D. Hansen, 1923. ASCSA Archives, Carl W. Blegen Papers.

“From ‘Warriors for the Fatherland’ to ‘Politics of Volunteerism’: Challenging the Institutional Habitus of American Archaeology in Greece.

Posted: February 1, 2020 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, History of Archaeology, Intellectual HIstory, Mediterranean Studies, Philhellenism | Tags: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Archaeological Institute of America, Colophon Excavations, Edward Capps, Hesperia, Jack L. Davis 3 CommentsDisciplinary history is not a miraculous form of auto-analysis which straightens out the hidden quirks of communities of scholars simply by airing them publicly. But it does force us to face the fact that our academic practices are historically constituted, and like all else, are bound to change.

Ian Morris, Archaeology as Cultural History, London 2000, p. 37.

Jack L. Davis. Created by Blank Project Design, 2020.

“Archives may be even more important than our publications” said Jack L. Davis in his acceptance speech on January 4, 2020, at the Annual Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America (AIA) in Washington D.C. Recognizing his outstanding career in Greek archaeology, the AIA awarded Davis, a professor of Classics at the University of Cincinnati and former Director of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (and a frequent contributor to this blog), the Gold Medal Award for Distinguished Archaeological Achievement. Earlier that day, in a symposium held in his honor, eight speakers highlighted Davis’s contributions to the field. Honored to be one of them, I presented a paper about a lesser known aspect of his career: his scholarship concerning the history and development of American Archaeology in Greece. An updated version of my paper follows below.

“Warriors for the Fatherland” (2000)

Jack Davis made his debut as an intellectual historian and historiographer in 2000 when he published “Warriors for the Fatherland: National Consciousness and Archaeology in ‘Barbarian’ Epirus and ‘Verdant’ Ionia, 1912-1922” (Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 13:1, 2000, pp. 76-98). Following “Warriors,” he published more than twenty essays of historiographical content in journals, collected volumes, and online platforms. Today I have chosen to review the ones that, in my opinion, offered counter-narratives challenging the institutional habitus of American archaeology in Greece. Read the rest of this entry »

Exploring the Relationship of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens with the Greek Omogeneia in the United States in the 1940s.

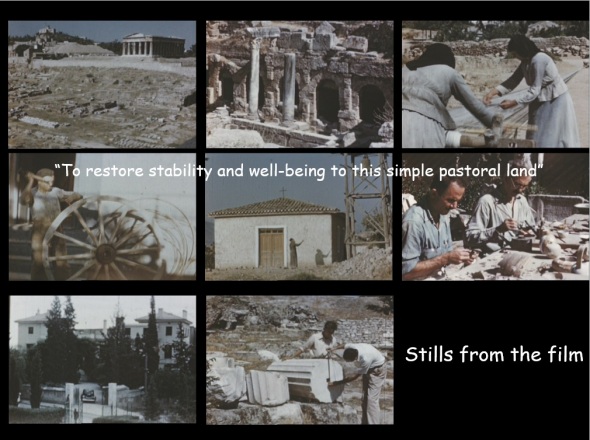

Posted: July 4, 2019 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, History of Archaeology, Mediterranean Studies, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism | Tags: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Greek War Relief Association, Nikolaos Mavris, Omogeneia, Oscar Broneer, Spyros Skouras, Theodore Leslie Shear, Triumph Over Time 7 CommentsIn 1947, the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or the School hereafter) produced a color movie titled Triumph over Time; it was directed by the archaeologist Oscar Broneer and produced by the numismatist Margaret E. Thompson with the aid of Spyros Skouras (1893-1971), the Greek American movie mogul and owner of Twentieth Century Fox (see Spyros Skouras Papers at Stanford University). Triumph over Time portrays Greece rebounding from World War II and the staff of the ASCSA preparing archaeological sites for presentation to postwar tourists. The film was made to promote the first postwar financial campaign of the ASCSA, the direct goal of which was to increase its capital and finance the continuation of the Athenian Agora Excavations. Indirectly, the ASCSA was hoping to contribute to the rehabilitation of Greece by providing employment for the Greek people and by promoting the economic self-sufficiency of Greece by developing the country’s tourist assets (Vogeikoff-Brogan 2007).

Oscar Broneer, ca. 1938. ASCSA Archives, Oscar Broneer Papers.

Triumph over Time begins with a brief overview of impressive Greek antiquities, such as the citadels of Mycenae and Tiryns and the Temple of Poseidon at Sounion, before continuing with rare ethnographic material capturing parts of rural Greece that no longer exist. It then moves from the Greek countryside to the buildings of the ASCSA, especially the Gennadius Library with its rare treasures. The story then covers the ASCSA’s two most important projects, the excavations at the Athenian Agora and at Ancient Corinth, explaining all stages of archaeological work. The documentary ends with a hopeful note that financial support of the ASCSA’s archaeological work will contribute to an increase in tourism so that this major source of revenue for Greece’s economy can “restore stability and well-being to this simple pastoral land.”

Stills from Triumph Over Time

On Finding Inspiration in Small Things: The Story of a Pencil Portrait

Posted: April 2, 2019 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Art History, Biography, Classics, History of Archaeology, Philhellenism | Tags: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Aristeides E. Phoutrides, Bert Hodge Hill, George Demetrios, John A. Huybers 14 CommentsMy story begins six years ago when we inventoried Bert H. Hill’s collection of photos at the item level. Among the images were early portraits of Hill when he was a little boy, and later, a handsome young man. A graduate of the University of Vermont (B.A. 1895) and Columbia University (M.A. 1900), Hill subsequently attended the American School of Classical Studies (ASCSA or the School hereafter) as a fellow for two years (1901-1903). He then secured a job as the Assistant Curator of Classical Antiquities at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (1903-1905) and lecturer at Wellesley College where he taught classes in sculpture. Bert Hodge Hill (1874-1958) was only 32 years old when he was appointed director of the ASCSA in 1906, a position he held until 1926.

Bert Hodge Hill, ca. 1910s. ASCSA Archives, Bert H. Hill Papers.

While processing the images my eye fell on a small portrait (12 x 9 cm) that was not a print but instead a well-executed drawing of Hill’s profile in pencil. On the back, Hill had scribbled “Huybers” and “BHH”. An initial web search for “Huybers artist” produced four of his pencil sketches in the Harvard Art Museums, a gift from George Demetrios in 1933 (keep the name in mind); the artist was identified as John A. Huybers.

Portrait of Bert Hodge Hill by John A. Huybers, ca. 1915-1920. ASCSA Archives, Bert H. Hill Papers.