Mrs. Jarley’s Waxworks and a Jolly Jumble of Jests, Christmas 1903

Posted: June 19, 2022 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Classics, History of Archaeology | Tags: Edith Hall, Fritz Darrow, Gorham Stevens, Harold Fowler, Katherine Welsh, Lacey Caskey, Theodore W. Heermance, Theosophy 4 CommentsThe story of Mrs. Jarley’s Waxworks forms part of Charles Dickens’s novel The Old Curiosity Shop, published in 1841. Although Mrs. Jarley is a minor character in the plot, her story gained much popularity in British and American amateur theater and was performed widely at private parties in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Inspired by Madame Tussaud’s famous wax models, Dickens’s Mrs. Jarley was the proprietor of a collection of still wax figures which she displayed on a stage protected by a cord.

In 1873, George Bradford Bartlett (1832-1896), an American from Massachusetts, published Mrs. Jarley’s Far-Famed Collection of Waxworks. Enriched with more characters, real and fictitious, Bartlett’s book is essentially a guidebook for staging amateur performances with animated pantomimes, also known as tableaux vivants. Unlike Dickens, Bartlett’s waxworks were fitted with clockworks inside so that they could move and “go through the same motions they did when living.” Louisa May Alcott (1832-1888), the author of Little Women, frequently participated in tableaux vivants, with Bartlett as her stage manager (Chapman 1992).

These kinds of performances were often used as a vehicle for local fund-raising. Socialites such as Mrs. Astor and Mrs. Vanderbilt often hosted tableaux vivants with young, unmarried women of high society performing in various roles (Chapman 1992).

One such performance took place at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or the School hereafter), on Christmas in 1903. It is one of these rare instances, where an event described blow-by-blow in a private letter, has also its visual match. In the School’s large Archaeological Photographic Collection (APC), in addition to photos documenting excavation and other fieldwork, there is a small number of images capturing more private aspects of life at 54 Speusippou (now Souidias).

According to the author of the letter, Theodore Woolsey Heermance (1872-1905), the idea of a party inspired by Mrs. Jarley’s Waxworks belonged to Mrs. Fowler, “who had seen and participated in several such.” Heermance was the new director of the School, having started his term in the fall of 1903. Just a year over thirty, he had studied at Yale and was the grandson of Theodore Dwight Woolsey, President of Yale University from 1846 to 1871. Helen Bell Fowler (1848-1909) was the wife of Harold Fowler, the School’s Professor of Greek Language and Literature for the academic year 1903-1904.

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

If the original idea of a tableau vivant belonged to Mrs. Fowler, it was Edith Hall “who took the matter up with her usual energy and consented to be Mrs. Jarley. Between them and Miss Welch [Welsh] – a member of the British School, who lives at the same pension as Miss Hall- they planned for the different parts,” wrote Heermance to his mother and sister on December 27, 1903. He further described the costumes “as more or less burlesque, otherwise with a limited outfit they would have fallen rather flat.”

Edith Hayward Hall (1877-1943) was the Agnes Hoppin Memorial Fellow and the only female student at the School that year. Having earned a B.A. from Smith College, Hall had enrolled at Bryn Mawr College for graduate school. That Christmas “Miss Hall as Mrs. Jarley was capital and with a big hat on kept up a continuous stream of description of her automations and of banter with the audience” wrote Heermance and went on to describe the wax figures “in the order they were uncovered and set agoing.”

“Darrow was Xerxes in a golden crown and neck ornaments and red robes. His business was to rise from his throne three times as Xerxes is said by Herodotus to have done on one occasion in anger.” Heermance is referring to a passage from Book VII of Herodotus that describes the Battle of Thermopylae: “And during these onsets, it is said that the king, looking on, three times leaped up from his seat, struck with fear for his army” [7. 212].

Front row (l-r): Harold Fowler (Agamemnon), Lacey Caskey (Columbus), William Battle (Baby Heracles), Gorham Stevens (Miss Muffet), Fritz Darrow (Xerxes). Back row (l-r): Edith Hall (Mrs. Jarley), Robert McMahon (Klytaimnistra), Harold Hastings (Lord Byron), May Darrow (Zoe or Maid of Athens), Katherine Welsh (Sappho), and Theodore Heermance (Mrs. Jarley’s Assistant).

The Cretan Enigma

Posted: May 20, 2022 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Classics, History of Archaeology, Philhellenism, Uncategorized | Tags: Charles Henry Hawes, Crete, Harriet Ann Boyd 1 CommentBY CURTIS RUNNELS – PRISCILLA MURRAY

In February 2022, Curtis Runnels, Professor of Archaeology at Boston University, and his wife Priscilla Murray, an anthropologist and Classical archaeologist, contributed to From the Archivist’s Notebook a story (The Cretan Idyll of Harriet Boyd and Charles Henry Hawes) about their purchase of a sketchbook from the early 20th century with watercolors depicting places and people on Crete. At the time, they identified Charles Henry Hawes as the owner of the sketchbook. Soon after their essay was published, they received a communication that cast doubt on the identity of the owner. After doing more research, they felt that they should publish an addendum to their previous essay, in order to let people know that they were probably wrong in their identification, and also open the floor for further discussion concerning the ownership of this precious item.

At a dinner in London in the nineteenth century, the social scientist Herbert Spencer is reported to have said that he had once composed a tragedy, to which the biologist Thomas Henry Huxley quickly replied “I know what it was about: an elegant theory killed by a nasty, ugly little fact.” Our blog “The Cretan Idyll of Harriet Boyd and Charles Henry Hawes” is such a tragedy. From circumstantial evidence we had concluded that a sketchbook in our collection was once owned by Charles Henry Hawes. But now archaeologist Vasso Fotou, who has a copy of Henry’s diary for the spring of 1905, has informed us that the dates in our sketchbook for that time period and the ones in Henry’s diary do not match. That fact proves that the sketchbook was not owned by Henry.

On the dates of the paintings and other sketches of the Aegean islands between Siteia and Athens in the sketchbook, Henry was on Crete. He had been on Crete for a few days when a group of attendees of the First International Congress of Archaeology in Athens, including Harriet Boyd, Sir Arthur Evans, and twelve others arrived in Candia aboard the chartered yacht Astrapi on April 13. Henry visited Harriet at Gournia on April 20, however, and not on April 16 as we had thought, and he remained in Crete after the Astrapi returned to Athens.

The dates in the sketchbook for 1905 suggest a short trip to Crete, and we now believe that it belonged to one of the twelve passengers on the Astrapi. The yacht continued on to the Bay of Mirabello and Siteia, allowing some of the passengers to visit the excavations at Gournia and Palaikastro before the yacht returned to Athens via the islands. Who was in that party of travelers and who could have been the owner? And which of these people is also responsible for the paintings, pencil drawings, and other pictures in New England in 1915 and 1916? It should be noted that the artworks in the sketchbook for both periods are of highly variable quality, and two pencil drawings (one of a sculpture of Heracles in the Mykonos Museum dated to April 20, and one undated portrait of the head of a man who might be Henry) are pasted into the sketchbook and are possibly from a different book. Did more than one person paint or draw in the book?

While the sketchbook was not Henry’s, we nevertheless know that the conference visitors were acquainted with Harriet and probably also with Henry whom they would have met on the side trip to Palaikastro where he was excavating. The acquaintance of the sketchbook owner with the Hawes may have been renewed in New England in 1915/1916 and it is possible that some of the portraits in the book are of Henry, Harriet, and their children after all.

We have considered two “suspects,” perhaps Edith Hall or Gisela Richter, both of whom were in Harriet’s circle and both of whom were on Crete in 1905 and who subsequently lived in the U.S. on the east coast in 1915/1916. Unfortunately, in the absence of any evidence tying either one of them to the sketchbook we can only speculate that one of these women, both close friends with Harriet, could be the sketchbook owner.

Recalling a Museum Theft

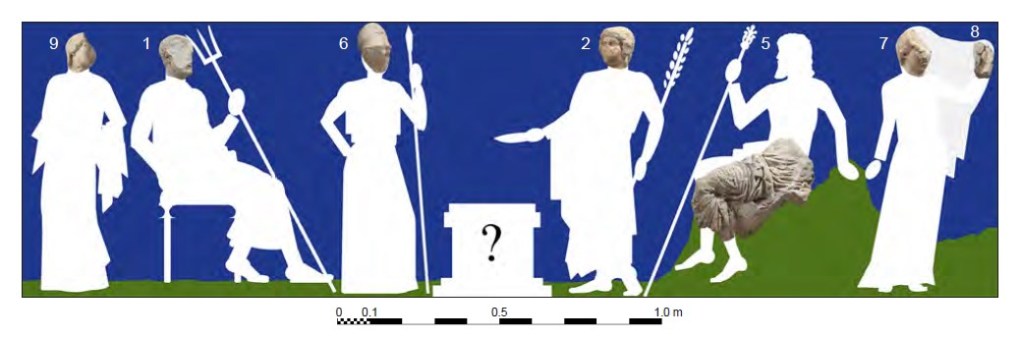

Posted: April 21, 2022 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Art History, Classics, History of Archaeology, Mediterranean Studies, Philhellenism | Tags: Athenian Agora Excavations, Charles H. Morgan, Christine Alexander, Eugene Vanderpool, Homer A. Thompson, Γιάννης Μηλιάδης, John L. Caskey, John Meliades 4 Comments“Sadly, the best candidate for him, the beautifully carved [head] 3, facing right, was stolen from the Agora’s dig house in 1955, while the Stoa of Attalos was under construction.” This sentence caught my attention while reading “Classical Sculpture from the Athenian Agora, Part 2: The Friezes of the Temple of Ares (Temple of Athena Pallenis),” published in Hesperia 88 (2019) by Andrew Stewart and seven co-authors (E. Driscoll, S. Estrin, N. J. Gleason, E. Lawrence, R. Levitan, S. Lloyd-Knauf, and K. Turbeville). Further below in the catalog entry for the head, the exact date of the theft is also mentioned: August 22, 1955.

Stewart et al. refer to a fragmentary male head of high craftsmanship that was found in the Athenian Agora near the northeast corner of the Temple of Ares in 1933. Carved around 430-425 B.C. and identified as Hermes, the small head (H.: 0.147m) is one of forty-nine half-size marble fragments which once decorated the friezes of the Temple of Ares in the Agora (originally the Temple of Athena Pallenis at Pallene). A plan of the Agora with the findspots of the sculptures is included in the Hesperia article, and is also available at https://ascsa.net.

Thefts occur in even the best guarded museums and libraries. Every institution has its own story (or stories) to share or hide. And at least some thefts are committed by those who have “hands-on” access to the collections. A recent example was the return of two valuable journals of Charles Darwin, which were stolen two decades ago from the library of Cambridge University. Others remain lost–the paintings stolen from the Isabella Gardner Museum in Boston in 1990, or the Telephus head, an original by Skopas, removed from the Tegea Museum in 1992.

But back to the little head of Hermes that was inventoried as S 305. I was curious to discover more about its theft. A search in the Archives of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or the School hereafter) yielded considerable information about the event and its aftermath.

Read the rest of this entry »The Charioteer of Delphi in the Clutches of WW II

Posted: March 16, 2022 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Classics, History of Archaeology, Modern Greek History | Tags: Alexandros Kontoleon, Antonios Keramopoulos, Delphi Charioteer, Hans von Schoenebeck, Ηνίοχος των Δελφών, Vasileios Petrakos, Wilhelm Kraiker 7 CommentsBY ALEXANDRA KANKELEIT

Alexandra Kankeleit, an archaeologist who specializes in the study of Roman mosaics, has also been part of an extensive project of the German Archaeological Institute (Athens and Berlin), titled The History of the German Archaeological Institute at Athens during the National Socialist Era. As part of the project, she has examined a host of bibliographic and archival sources in both countries that document activities of German archaeologists in Greece from 1933 until 1944. Here she contributes an essay about the adventures of the Delphi Charioteer during the German Occupation in Greece.

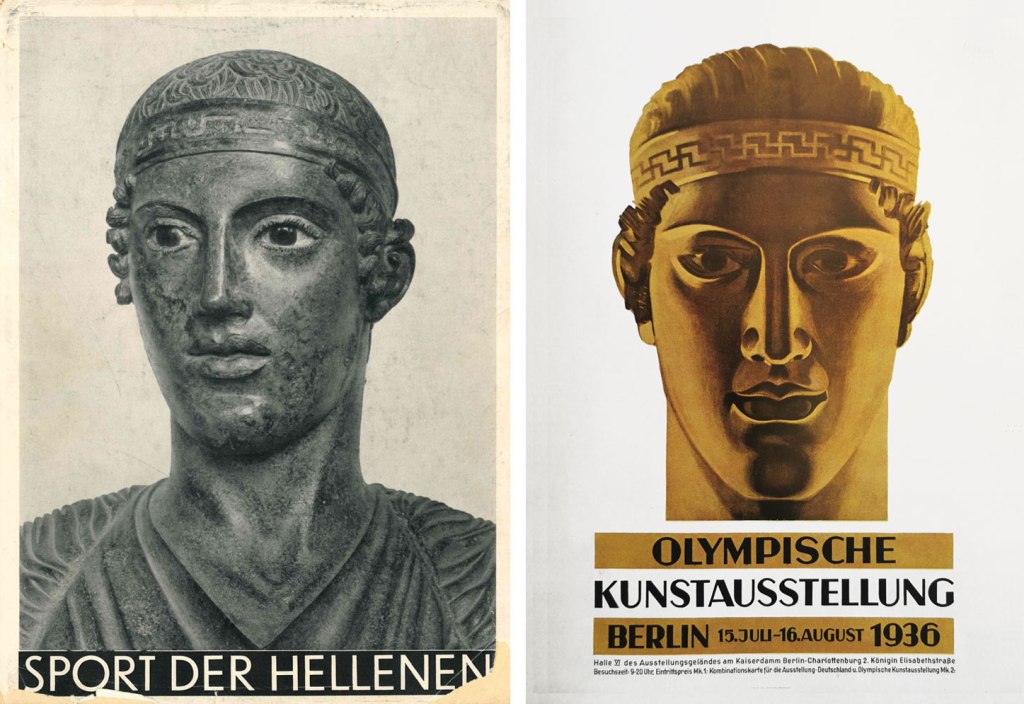

The Charioteer of Delphi (Ο Ηνίοχος των Δελφών) is one of the best-preserved and most important bronze statues of ancient Greece. Since its discovery in 1896, it has been one of the main attractions of the Archaeological Museum in Delphi. As a symbol of ancient civilization and the eventful history of Greece, it is still a frequently recurring motif in the visual and performing arts (Figs. 1-2).

During the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, the Charioteer was promoted together with the Discobolus of Myron and the Boxer of the Quirinal as the prototype of the Greek athlete in antiquity (see Olympia Zeitung 3, July 23, 1936, p. 46). Thus, his face adorned the covers of catalogs and propaganda material circulated in 1936 on the occasion of the Olympiad (Figs. 3-4).

German scholars also increasingly turned their focus on the Early Classical masterpiece. In his Habilitation “Der Wagenlenker von Delphi” (The Charioteer of Delphi), the archaeologist Roland Hampe (1908-1981) pursued his goal of reducing the many “ambiguities, misunderstandings, differences of opinion” concerning the monumental bronze group. His manuscript was completed in August 1939 and published as a monograph in 1941 (Hampe 1941).

Read the rest of this entry »The Cretan Idyll of Harriet Boyd and Charles Henry Hawes

Posted: February 12, 2022 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Art History, Biography, Classics, Crete, Greek Folklore, History of Archaeology, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism, Women's Studies | Tags: Charles Henry Hawes, Crete, Harriet Ann Boyd 6 CommentsBY CURTIS RUNNELS – PRISCILLA MURRAY

Curtis Runnels, Professor of Archaeology at Boston University and an expert in Palaeolithic archaeology in Greece, and his wife Priscilla Murray, an anthropologist and Classical archaeologist, here contribute to From the Archivist’s Notebook a story about their purchase of a sketchbook from the early 20th century with watercolors depicting places and people on Crete.

We visited an antiquarian bookfair in Concord, New Hampshire, about twelve years ago and a booth belonging to a dealer from Vermont, who specialized in original artwork, caught our eye. Sorting through piles of miscellaneous materials, we found a few things relating to Greece, and a small (8 by 4 inches; 20 x 10 cm) artist’s sketchbook grabbed our attention. It was displayed on a table opened to a watercolor view that seemed familiar. Surely it was the entrance to the harbor at Herakleion on Crete! And indeed, penciled in one corner was the inscription “Candia,” the older name for the city which both confirmed the identification and provided a clue that the sketchbook, as dealers in antiques like to say, “had some age.” There were other artworks in the sketchbook that are dated to April 1905, and still others with various dates in 1915, and one dated to 1916. The artwork from 1905 was the most interesting for us. Turning the pages of the sketchbook we saw line drawings of dancers at Knossos and a man drawing water from a well in Siteia, pastels of houses labeled Knossos and “Sitia, as well as watercolors and line drawings of Mykonos, Ios, and other Cycladic islands, Sounion, and Athens. The unknown artist was interested particularly in the new Minoan finds from Knossos as is evident from the line drawings of wall paintings and artifacts in the “Candia Museum.”

Although there is no artist’s signature, we guessed that the artist must be someone interesting, perhaps even someone we would recognize. After all, how many Americans or British travelers (the fact that the titles are in English is the reason for assuming the nationality of the artist) were sufficiently interested in Knossos and the Minoans to visit Crete in 1905 at a time when there was much unrest on the island? We bought the sketchbook and took it home to do more research.