Becoming: Bert Hodge Hill, 1906-1910 (Part I)

Posted: January 1, 2024 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Crete, History of Archaeology, Mediterranean Studies, Modern Greek History, Uncategorized | Tags: Archaeology, Athens, Bert Hodge Hill, europe, George W. Elderkin, greece, James R. Wheeler, Kendall K. Smith, Mochlos, Richard Berry Seager, Theodore W. Heermance, travel 10 CommentsThe re-discovery of a small cache of old photos depicting students at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or School hereafter) from 1907-08 inspired me to write about the first years of Bert Hodge Hill’s directorship at the School. [1]

The photos depict four men and one woman: George Wicker Elderkin (1879-1965), Kendall Kerfoot Smith (1882-1929), Charles Edward Whitmore (1887-1970), Henry Dunn Wood (1882-1940), and Elizabeth Manning Gardiner (1879-1958). Of the five, Elderkin, Smith, and Wood were second year students at the School. In 1908, Elderkin, who already held a PhD from Johns Hopkins (1906), succeeded Lacey D. Caskey as Secretary of the School, a position he held for two years (1908-10). Smith came to the School in 1906 holding the Charles Eliot Norton Fellowship, established by James Loeb in 1901 for Harvard or Radcliffe students. Wood, a trained architect with a BS in Architecture from the University of Pennsylvania, was the second recipient of the Fellowship in Architecture (1906-08) that was funded by the Carnegie Institution in Washington.

Of the new students, Whitmore, another Harvard man, was the Charles Eliot Norton Fellow for 1907, and Gardiner, the only woman in the photos, was a graduate of Radcliffe College (1901), with an MA from Wellesley (1906), and a recipient of the Alice Palmer Fellowship that supported female students.

Read the rest of this entry »Mrs. Jarley’s Waxworks and a Jolly Jumble of Jests, Christmas 1903

Posted: June 19, 2022 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Classics, History of Archaeology | Tags: Edith Hall, Fritz Darrow, Gorham Stevens, Harold Fowler, Katherine Welsh, Lacey Caskey, Theodore W. Heermance, Theosophy 4 CommentsThe story of Mrs. Jarley’s Waxworks forms part of Charles Dickens’s novel The Old Curiosity Shop, published in 1841. Although Mrs. Jarley is a minor character in the plot, her story gained much popularity in British and American amateur theater and was performed widely at private parties in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Inspired by Madame Tussaud’s famous wax models, Dickens’s Mrs. Jarley was the proprietor of a collection of still wax figures which she displayed on a stage protected by a cord.

In 1873, George Bradford Bartlett (1832-1896), an American from Massachusetts, published Mrs. Jarley’s Far-Famed Collection of Waxworks. Enriched with more characters, real and fictitious, Bartlett’s book is essentially a guidebook for staging amateur performances with animated pantomimes, also known as tableaux vivants. Unlike Dickens, Bartlett’s waxworks were fitted with clockworks inside so that they could move and “go through the same motions they did when living.” Louisa May Alcott (1832-1888), the author of Little Women, frequently participated in tableaux vivants, with Bartlett as her stage manager (Chapman 1992).

These kinds of performances were often used as a vehicle for local fund-raising. Socialites such as Mrs. Astor and Mrs. Vanderbilt often hosted tableaux vivants with young, unmarried women of high society performing in various roles (Chapman 1992).

One such performance took place at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or the School hereafter), on Christmas in 1903. It is one of these rare instances, where an event described blow-by-blow in a private letter, has also its visual match. In the School’s large Archaeological Photographic Collection (APC), in addition to photos documenting excavation and other fieldwork, there is a small number of images capturing more private aspects of life at 54 Speusippou (now Souidias).

According to the author of the letter, Theodore Woolsey Heermance (1872-1905), the idea of a party inspired by Mrs. Jarley’s Waxworks belonged to Mrs. Fowler, “who had seen and participated in several such.” Heermance was the new director of the School, having started his term in the fall of 1903. Just a year over thirty, he had studied at Yale and was the grandson of Theodore Dwight Woolsey, President of Yale University from 1846 to 1871. Helen Bell Fowler (1848-1909) was the wife of Harold Fowler, the School’s Professor of Greek Language and Literature for the academic year 1903-1904.

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

If the original idea of a tableau vivant belonged to Mrs. Fowler, it was Edith Hall “who took the matter up with her usual energy and consented to be Mrs. Jarley. Between them and Miss Welch [Welsh] – a member of the British School, who lives at the same pension as Miss Hall- they planned for the different parts,” wrote Heermance to his mother and sister on December 27, 1903. He further described the costumes “as more or less burlesque, otherwise with a limited outfit they would have fallen rather flat.”

Edith Hayward Hall (1877-1943) was the Agnes Hoppin Memorial Fellow and the only female student at the School that year. Having earned a B.A. from Smith College, Hall had enrolled at Bryn Mawr College for graduate school. That Christmas “Miss Hall as Mrs. Jarley was capital and with a big hat on kept up a continuous stream of description of her automations and of banter with the audience” wrote Heermance and went on to describe the wax figures “in the order they were uncovered and set agoing.”

“Darrow was Xerxes in a golden crown and neck ornaments and red robes. His business was to rise from his throne three times as Xerxes is said by Herodotus to have done on one occasion in anger.” Heermance is referring to a passage from Book VII of Herodotus that describes the Battle of Thermopylae: “And during these onsets, it is said that the king, looking on, three times leaped up from his seat, struck with fear for his army” [7. 212].

Front row (l-r): Harold Fowler (Agamemnon), Lacey Caskey (Columbus), William Battle (Baby Heracles), Gorham Stevens (Miss Muffet), Fritz Darrow (Xerxes). Back row (l-r): Edith Hall (Mrs. Jarley), Robert McMahon (Klytaimnistra), Harold Hastings (Lord Byron), May Darrow (Zoe or Maid of Athens), Katherine Welsh (Sappho), and Theodore Heermance (Mrs. Jarley’s Assistant).

On the Trail of the “German Model”: ASCSA and DAI, 1881-1918

Posted: August 10, 2020 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, History of Archaeology, Women's Studies | Tags: Adolf Wilhelm, American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Eugene P. Andrews, Georg Karo, German Archaeological Institute Athens, Germanophilia, Nellie M. Reed, Ruth Emerson Fletcher, Theodore W. Heermance, Wilhelm Dörpfeld 14 CommentsFounded in 1881, the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (hereafter ASCSA or the School) was the third foreign archaeological school to be established in Greece and followed the French and German models. For the first thirty years, the activities of the American School were closely intertwined with those of the German Archaeological Institute at Athens (DAI or German Institute hereafter) and the Austrian Archaeological Institute of Athens (Austrian Institute or Station hereafter).

Eloquent testimony to their informal relationship is found in the ASCSA Annual Reports (AR) from 1887 onwards, where the directors of the American School repeatedly extended their profound gratitude to Wilhelm Dӧrpfeld, Director of the German Institute (1887-1912), Paul Wolters, Second Secretary of the German Institute (1887-1900), and Adolf Wilhelm, Secretary of the Austrian Institute (1898-1905), for allowing American students to attend their weekly seminars and archaeological excursions. Only occasionally, would the ASCSA similarly express its gratitude to a French or British colleague. In fact, the ASCSA relied so heavily on the German Institute that it delayed developing an independent academic program of its own until Dӧrpfeld stopped offering his lectures and tours in 1908.

In order to reconstruct the early decades of the School’s history and its relationship to the German Institute, in addition to the Annual Reports, I have also relied on a second type of primary source: personal correspondence and diaries. Both are rare, however. Unlike official documents that have a greater chance of survival (sometimes in more than one copy) the preservation of family correspondence is a matter of luck. Of the 200 men and women who attended the School’s academic program from 1881 to 1918, the outgoing letters of fewer than a dozen members have survived, and of those only the letters of few have found their way back to the School’s Archives.

By nature, each type of source provides the researcher with different kinds of information, even if both sources refer to the same people or events. Official reports are formal and, to a certain extent, sanitized documents that deliver the governing body’s mindset. I, personally, find private correspondence a more insightful source, although it can be subjective and overstated; nevertheless, it is the best thing that a historian has at his/her disposal for reconstructing the past because its testimonies offer contemporary perspectives. At a time when cell phones, text messages, and social media were not available, a letter was the only way for reporting one’s activities and also for expressing one’s feelings. Glimpses, for example, at the private correspondence of Nellie M. Reed, student of the School in 1895-1896, reveal a continuous stream of informal American-German gatherings during that year, otherwise undocumented in the Annual Reports.

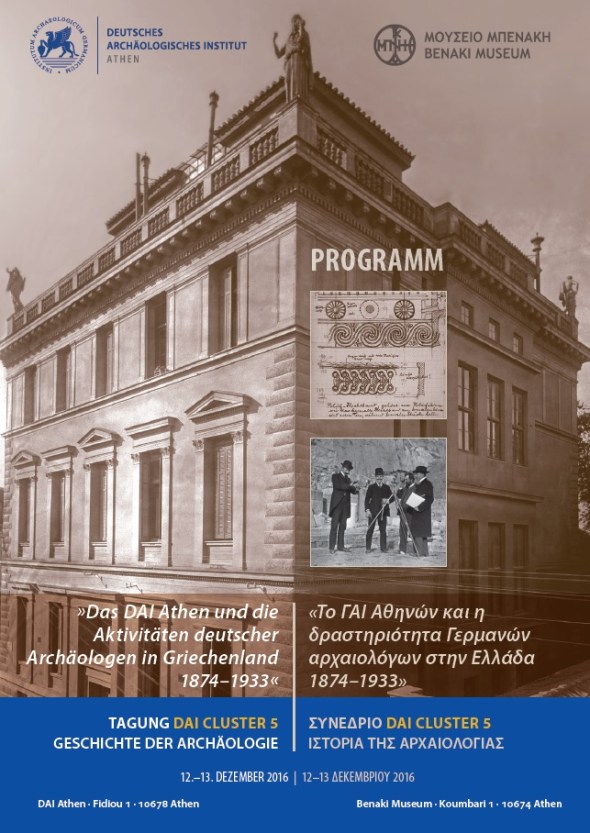

In 2016, I was invited to participate in a conference that explored the early history of the German Archaeological Institute at Athens. I used that event as an opportunity to study and re-write the “German chapter” in the history of the American School.[1] The narrative explores the catalysts that brought these two groups together and asks: Was it simply the vibrant and charismatic personality of Dӧrpfeld, who for three decades dominated the archaeological community of Athens, that was responsible for the rapprochement of the two institutions in the closing decades of the 19th century, or did the School’s close ties with the German and Austrian institutes reflect a larger educational trend that prevailed in American academic circles in the second half of the 19th century?

Phantom Threads of Mothers and Sons

Posted: May 1, 2018 Filed under: Archival Research, Biography, History of Archaeology | Tags: Anna Blegen, Bert Hodge Hill, Carl W. Blegen, Catherine Munro Schurman, John Gennadius, Phantom Thread, Richard B. Seager, Theodore W. Heermance 8 Comments“Dear Mother: How far are we responsible for already inherited faults? That old Sam Hill, by whom folks used to swear when they dared not take greater names in vain, brought over to Vermont at the end of the eighteenth century among his numerous children one son, Lionel, destined to surpass in dilatoriness all the other slow-going Hills of his generation. He married very tardily and begat two sons, both in due time notable procrastinators, the greater of them being the younger, named Alson, who added to more than a full measure of the family instinct for unreasoning delay an excellent skill in finding good reasons for postponing whatever was to be done. Alson Hill was my father…”. Bert Hodge Hill (1874-1958) addressed these thoughts to his mother from Old Corinth on February 28, 1933 when he was almost 60 years old. Hill, however, never mailed the letter because she had died when he was barely four years old.

Bert Hodge Hill as a young boy and as a middle-aged man. ASCSA Archives, Bert H. Hill Papers.

We will never know what prompted Hill to compose this imaginary missive to a person he never knew. It is the only document, however, that has survived among Hill’s papers that gives us a hint of latent childhood trauma. Just google “mothers and sons” and you will get titles such as “Men and the Mother Wound”, “The Effects of an Absent Mother Figure,” and so forth, with references to a host of scientific articles about the decisive role played by mothers. Hill’s dilatoriness cost him the directorship of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or the School hereafter) in 1926, after having served as the School’s Director for twenty years. Hill never even finished his imaginary letter to his mother. Had she been around when he was growing up, would have she corrected this family defect and taught him how to prioritize and achieve timely and consistent results? Hill must have wondered. Read the rest of this entry »