Athens at the Turn of the Century: A Sentimental Capital and a Resort of Scholars

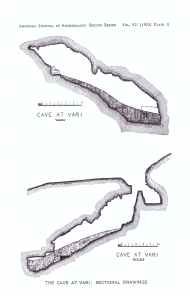

Posted: April 1, 2017 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Food and Travel, History of Archaeology, Mediterranean Studies, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism, Women's Studies | Tags: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Charles H. Weller, George Horton, Ida Thallon Hill, Lida Shaw King, Vari Cave 10 CommentsOn February 17, 1901, a young American archaeologist and member of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or the School hereafter) was “roaming over the city in search of Mr. Kavvadias, the general ephor of antiquities in Athens, in order to get a permit to begin work at Vari tomorrow” (letter of Charles H. Weller to his wife). Together with a small group of students from the School, he had conceived of the idea of conducting a small excavation at the Vari Cave on the southern spur of Mount Hymettus, near the ancient deme of Anargyrous. Known since the 18th century, the cave had been visited and described by several European travelers who were particularly taken by the reliefs and inscriptions carved on its walls.

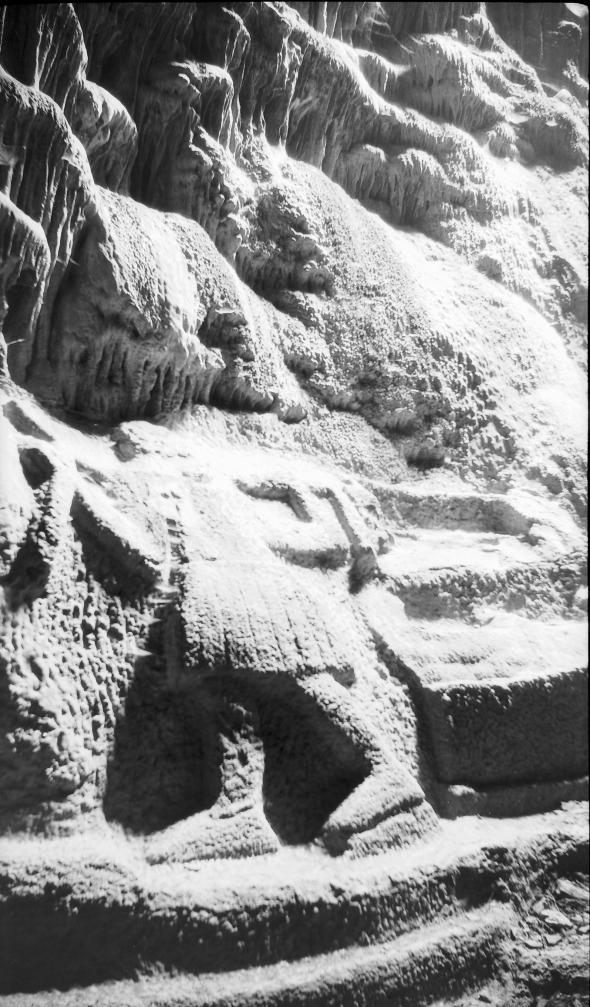

Vari Cave interior with sculpted figures, 1923. Source: ASCSA Archives, Dorothy Burr Thompson Photographic Collection.

In 1765, one such visitor, Richard Chandler, re-discovered the cave, which he described in his Travels in Greece or an Account of a Tour Made at the Expense of the Society of Dilettanti (Oxford 1776, p. 150). “You descend through a small mouth; the forked trunk of a tree… serving as a ladder. At the landing place is a Greek inscription very difficult to read. It is cut on the rock first smoothed, and informs us, that Archidamus of Pherae made the cave for the Nymphs, by whom he was possessed… When you are down and face the stairs, at the extremity on the right hand is an ithyphallus, the symbol of Bacchus… Under small niches in two places, is inscribed, “Of Pan”… Beyond there is a very rude figure of the sculptor represented with his tools, as working, and by it his name, Archidamus, twice repeated, the letters irregular and badly cut…”

Plan and section of the Vari Cave as published in AJA 1903.

Its excavation seemed like a worthy project for the group of young, adventurous, and aspiring archaeologists attending the school in 1901. The original idea belonged to Weller, a recent PhD from Yale University, who invited the slightly older Maurice Edwards Dunham, also from Yale, to join in the endeavor. Soon, two more students, Lida Shaw King and Ida Thallon, offered to take part and contribute $10 each; Edward D. Perry, the Visiting Professor for 1900-1901, chipped in another $15. With this funding (the equivalent of $1,000 today) and the approval of ASCSA director Rufus B. Richardson, the team made plans for a two-week excavation. It would be the School’s first new project since 1895, when it launched the Corinth excavations and digs at Eretria and the Argive Heraeum, which were now finished. “Gone were the days when the School could spread devastation over the face of the land by attacking theaters and ruined Byzantine churches in seven different sites in one season” wrote Louis E. Lord summarizing the ASCSA’s new excavation policy after 1895 (Lord, History of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1881-1942, Boston 1947, pp. 84-85).

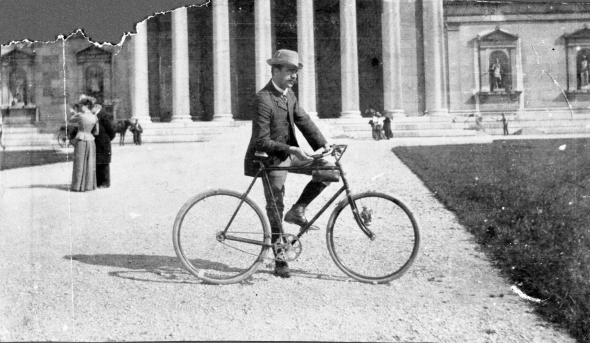

Charles Weller, an ardent biker, on his way to Greece, 1900. Source: ASCSA Archives, Charles H. Weller Papers.

Just a year before, Richardson had not allowed Harriet Boyd to participate in the Corinth excavations on the grounds that women “could not endure the hardship of an active excavation” (Lord 1947, p. 95). Proving him wrong, Boyd went on to lead her own field mission on the island of Crete, excavating first at Kavousi in 1900 and a year later at Gournia. Creating her own legend, Boyd became a source of inspiration for many women at the School in the early 1900s, including Ida Thallon (later Hill).

“She has a man servant who rejoices in the name of Aristeides and who wears a fustanella. The only other fustanella servants in town belong to the Queen and the Schliemanns, but Miss Boyd is far too grand when she has him on the box,” wrote an impressed Ida to her mother in the early months of 1900.

Despite his initial permission allowing the two women (King and Thallon) to participate in the excavation, Richardson soon reneged, using as an excuse the absence of a chaperone. This feeble logic must have been particularly galling since one of the women, King, was 33 years old and an instructor of Greek and Latin at Vassar College. She had “chaperoned so many parties that it had not occurred her” that she would need a chaperone herself to dig at Vari (Weller to his wife, Feb. 15, 1901). In the end it was agreed that the women could participate in the excavation if they did not stay overnight in the dig house.

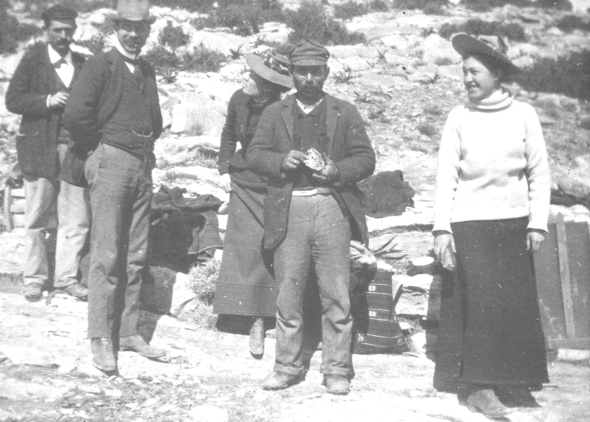

Charles Weller (second left) and Ida Thallon (right) excavating the Vari Cave, 1901. ASCSA Archives, Archaeological Photographic Collection.

On February 19th, 1901, Weller, his team, and ten workmen from the neighboring village began the excavation of the cave. He described a slow project since “each basket full or half full of dirt had to be pulled up by a rope by two men, while a third unties the rope and empties…Oh, I suppose we are getting pretty good work from them but it seems pretty slow from an American point of view.” The same evening Weller’s workforce went on strike for more pay and he noted in a letter to his wife that he was forced to “yield though not till after a struggle. It is no snap to face a strike with a language that you don’t know.” A few days later he admitted that the work was hard enough to justify raising the workers’ wages.

“I enclose for you a picture of our gang at Vari. [Herbert] De Cou says they look like a ‘precious lot of cut throats,’ and I guess they do, but I can testify to their good and jolly character. I think too that I could get them to defend me in great shape. I know they will be willing after they each get the pictures that I am going to send them” (March 13, 1901).

Weller’s gang at Vari, 1901. Source: ASCSA Archives, Charles H. Weller Papers.

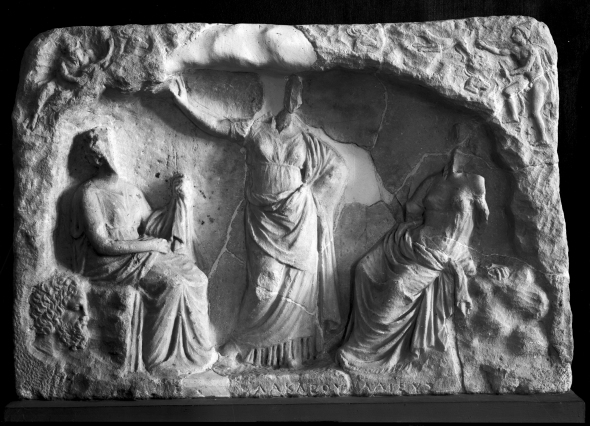

The excavation uncovered a number of marble dedicatory reliefs, hundreds of lamps, fragments of figurines and pottery, and many coins. On the last day of the excavation, March 1st 1901, the team packed all the finds for the trip to Athens. “Have 50 fragments of marble reliefs, about 150 coins, 4 baskets of lamps, 2 or 3 baskets of the best pottery fragments, a number of terracotta statuettes including three or four very good heads and several inscriptions. Feel much pleased with the results,” wrote young Ida in her diary. The study of the finds showed that the cave had been used from the 6th century B.C. until well into the Roman times. Weller not only dug the cave but also published the results of the excavation in a collaborative spirit. The long report in the American Journal of Archaeology (AJA, 1903) listed a number of contributors besides Weller, who provided the overall account of the excavation. They include Dunham (inscriptions), Thallon (marble reliefs), King (vases, figurines, and small finds), Agnes Baldwin (coins), and Samuel E. Bassett (lamps).

One of the reliefs discovered at Vari Cave (now at the National Archaeological Museum). Source: ASCSA Archives, Archaeological Photographic Collection.

The excavation of the Vari Cave was the first career step for many of the participants. Weller, after teaching at Hopkins School in New Haven, would move to the University of Iowa to teach Greek and art history until his death in 1927. In 1924, inspired by his love for good photography and his talent for writing, Weller established and led Iowa University’s School of Journalism. His youngest daughter Ruth Weller Nelson McCuskey would become a professional photographer, and it was in her basement that her niece (Weller’s granddaughter, from his older daughter Clara), Jeanne Perrin, would discover a treasure-trove of photos from Weller’s time in Greece (1900-1901 and 1910.)

Dunham, after a brief career as a professor of Classics at the University of Colorado at Boulder, would die two years later, just as his article on the Vari inscriptions was going to press. Ida Thallon would continue her studies at Columbia University where she received her PhD in 1905. Dedicated to Vassar, Ida would return to her alma mater to enjoy a distinguished teaching career as a professor of Greek and Latin until her marriage to Bert Hodge Hill in 1924. From that point on Ida Thallon Hill and friend Elizabeth Pierce Blegen would become key figures in the Athenian archaeological community (both women are featured in many of my posts). Ida would maintain her close relationship with Lucy Shaw King. After completing her study of the Vari figurines, Lucy became a university administrator, serving many years as the dean of Pembroke College at Brown University; unfortunately, she never returned to Greece. Unlike the others, Agnes Baldwin had not participated actively in the Vari excavation; however, her publication of the coins from the cave was the first step in a long and illustrious career as a numismatist. She became the first female curator of the American Numismatic Society (ANS) in 1910 and her photographic collection in the Archives of the ANS, available online through FLICKR, is a treasure-trove of information about life in Athens at the turn of the century.

GOING TO COURT BALLS AND PLAYING GOLF

In addition to Weller’s and Baldwin’s photos of Athens in the early 20th century, one learns a lot about everyday life in the city at the turn of the century from Weller’s letters to his wife and the letters that Thallon sent to her mother (transcripts of which are saved in the ASCSA Archives). To these we could add a third source, a wonderful guide-book by George Horton (1859-1942), the well-known philhellene diplomat, titled Modern Athens (1897, 1901). (Modern Athens is available online, and it has also been translated into Greek by Alcestis Dema, Patakis Editions, 1997.) Horton served as U.S. consul in Athens in 1893-1898, and again from 1905 to 1906. Shortly after the Olympic Games of 1896, Athens became a popular destination for British and Americans tourists. To assist this new clientele, expatriates with long-term residency in Athens, such as Horton or Rufus B. Richardson, Director of the ASCSA (1893-1903), produced literary travelogues.

While all three sources (Weller, Thallon, and Horton) agree on many aspects of everyday life in Athens, their accounts also differ, as expected, in some areas. Weller, a scholar of modest means and a married man with two toddlers in America, avoided unnecessary expenses. Unlike Ida Thallon who could afford to stay in and eat multi-course dinners at the lavish Merlin House, Weller boarded with the Poulios family on Demokritou street. He frequently ate his meals, which consisted of “fried eggs, bread, a cup of chocolate and a rizogalo [rice pudding],” in the town’s milk shops, and his letters home often make mention of his threadbare clothes.“The pair I last sent in the wash were mostly holes. The wash lady put in whole new heels and toes but in such a way that with close shoes I can’t begin to wear them” (March 11, 1901). I also suspect that Weller’s lack of suitable clothes did not allow him to attend the New Year’s ball at the Greek Palace, which Ida attended twice (1900 and 1901), having come to Athens with a wardrobe appropriately equipped for such occasions. For the court ball, she wore her “white,” which was not as stunning as her black, which she could not wear because, as she explained to her mother, of the two rules about formal female clothing in Athens. “First can’t wear black; second must be off at the shoulders or at least very low. No white feathers or long train unless you like” (Jan. 12, 1900).

Boarding with Charilaos Poulios’s family on Demokritou Street. Source: ASCSA Archives, Charles H. Weller Papers.

Thanks to Ida, we have a blow by blow description (three single-spaced pages) of one court ball. Unlike Horton who found Greek upper class women quite fashionable (p. 21) as well as “dashing horse riders” (p. 71) -Horton would marry a Greek in 1909- Ida did not have one good word to say about the women she met at the ball. “Of course there were some pretty ones but very few and the rest were such guys. They are either very thin with washboard necks or very much the other extreme and they get to look old very soon; they do not hesitate to improve on nature and lay the paint on with whitewash brush. They look terrible disagreeable too, as if they had nasty tempers. They like white dresses and wear them very low. Some of the hair was astonishing to see. The women are not as polite as the men, they shove fearfully; of course there were some nice ones, but on the whole, they couldn’t touch American girls for looks” confided Ida to her mother. On meeting the Queen, Ida “made a grand courtesy, you can imagine about as graceful as a cow and took her hand but she wouldn’t let us kiss it, she shook hands instead and was so nice. She did let Greeks kiss her hand” (Jan. 18, 1900). Ida’s chauvinism, however, suffered a blow a few days earlier at the Merlin House. When she asked one of her boarding mates, Miss Kohler, “the exceedingly queer little English girl who follows the dowdy rather than stunning type,” if she was going to the court ball, Kohler responded: “Oh, no, when you have a court and a Queen of your own, things here look very small!” (Jan. 12, 1900).

Ida Thallon Hill, ca. 1900. Source: ASCSA Archives, Ida Thallon Hill Papers.

A month later Ida with Lida would also attend Madame Schliemann’s ball “which was a great success.” They had not been in the Schliemann house but had heard a lot about it. They expected to find a “very gorgeous and giddy” place, but instead found it “very attractive and in spite of its palatial size… very homelike and comfortable.” They were also impressed by Madame Schliemann and her lovely daughter Andromache Melas. Although “the Greeks do not, as a rule, introduce people, and we understood from Mrs. Richardson that Mme Schliemann didn’t,” both girls were pleasantly surprised when they were introduced to lots of men. “There were a great many naval officers there so we frisked about gaily with these gorgeous uniforms.” As always, I found their descriptions of the food interesting. Ida noted to her mother (Feb. 5, 1900) that instead of a single meal the supper room was open all the time “and you go and come just as you like. They don’t have hot things like consume [sic] or oysters; only hot things are tea and coffee and they have the greatest assortment of drinks, beer and punch, champagne, lemonade, etc. and fine fancy cakes and ices, candies, etc.”. Another surprising observation is that these fancy balls went on until early in the morning. “We came home about half past two… but it didn’t end till six.”

The Schliemann House in Athens, ca. 1890. Source: ASCSA Archives, Oscar Broneer Papers.

Ida was not excessively wealthy, but she had the means to sustain an upper-class lifestyle while a student in Athens. Unlike Weller who constantly worried about money, Thallon rarely expressed similar concerns in her letters. Without neglecting her obligations as a student at the American School, Ida and Lida led a busy social life with lots of tea and dinner parties organized by Mrs. Richardson, members of the U.S. legation, and a few Americanized families such as the Kalopothakes or the Schliemanns. In January 1900, she added one more activity to her weekly schedule.

“You will never guess what we were doing; playing golf,” she wrote triumphantly to her mother. “They have had the links ready for two or three weeks, but this was the first time we had gone out…Of course, they are not very wonderful links, but good fun and in the loveliest situation, you can possibly imagine, almost under the side of Hymettus and with such a view… I am glad I brought my clubs which have been collecting dust at a fearful rate for some time… We had only one set of clubs for three but that is a trifle; of course you can’t buy them here” (Jan. 25, 1900).

During another visit to the golf course she scribbled that “it took us a long time to go around for the King was playing right in front of us and we did not want to yell “fore” at him too vigorously, neither did we want to hit him in his royal head with a golf ball…” (March 6, 1900). Searching the history of golf in Greece on the internet revealed no information about this course which was later replaced by the new links in Glyfada in the 1960s (I welcome any information).

NERVOUS FOREIGNERS WOULD DO WELL TO AVOID GREEK FUNERALS

One subject that the two men, but not Ida, described in great detail and with some humor, despite its macabre content, is the spectacle of a Greek funeral. Horton suggests that “nervous foreigners would do well to avoid, the possibility of getting an unexpected view of the corpse, which is carried exposed in a shallow coffin” (p. 65), but he feels that he has to include it in his guide-book since the “dead were borne for the last time through the streets of the city which had been their home.” No did Weller shy away from the spectacle. He instead “got a fine picture of a part of it, including the gentleman most interested… To see the open coffin with the body rolling back and forth occasionally is quite interesting” (Jan. 22, 1901). In fact, after the funeral, one of the relatives tracked Weller down and asked for a copy of the photograph! As photographs were rare at the time and most people were photographed only in a photographer’s studio, an extra portrait of the deceased would have been a valuable addition to the family’s small photographic collection.

Greek funeral as illustrated by Corwin Knapp Linson. Source: George Horton, Modern Athens (1901), p. 66.

“AS A LAMB BEFORE HIS SHEARERS” AND THE GREEK EASTER

The rituals of Greek Easter have always had a special appeal to foreigners visiting Greece. Both Horton and Weller describe at length the procession of the Epitaph on Good Friday and the midnight celebrations with the crowd kissing each other and exchanging good wishes: “Christ is risen; he is risen indeed.” “Then the congregation breaks up and goes home, still carrying the lighted candles that soon scatter all over the city, like little lines and squads of moving stars. The first thing the Greek does when he reaches home is to light, from his candle, the lamp which burns before the icon, then he breaks the long fast with a dish of soup, made from the entrails and feet of the Easter lamb, seasoned with egg and lemon [i.e., mageiritsa]. But a small portion is taken, for it is necessary to prepare the stomach for the feasting of the morrow. It is a pretty poor Greek who cannot afford at least a piece of lamb on Easter Sunday, although he may not eat meat any other day of the year” (Horton, p. 70). Weller, who was writing to his wife (and not trying to impress his readers), gives his own version of the Easter preparations.

“Easter is a big season here and the lambs have to suffer for it. I do not know yet the significance of them, but each well to do family has one or two and sometime tomorrow there will be a general butchery of the innocents… The lamb at Poulios house is quite a pet today. He was even under the dining table when I ate today… I don’t know how many times I have remembered today the ‘As a lamb before his shearers is dumb, so he openeth not his mouth’” [Isaiah 53:7].

A TALE OF TWO CITIES

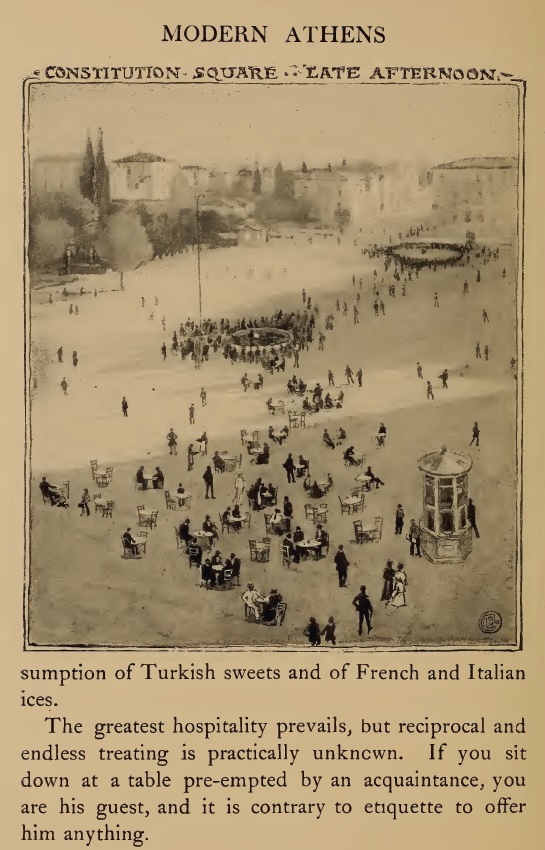

George Horton in Modern Athens recounted a tale of two cities, “each differing from the other in climate, in traditions, and to a great extent, in character of population.” Horton’s winter city, was a European city, “the resort of tourists, diplomats, and climate seekers,” where one ate “course dinners at the Angleterre Hotel,” attended service at the English church, danced “the barn dance at Madame Schliemann’s,” and played “charades in the library of the American School” (p. 1). This state of affairs lasted from October until May. “Then all changed. The diplomats and the climate-seekers hide them away, and the tourists cease to come” (p. 2). The summer city swarmed with Greeks from Egypt, Turkey, and Roumania, who drank resin wine and masticha, ate “pilaf, stuffed courgas, and fish with garlic-sauce, by candle light in the squares,” and attended open-air theaters.

In 1900-1901, Charles Weller had experienced Horton’s winter Athens without the course dinners and the fancy balls. When he returned to Greece in 1910 for a brief visit, it was late June. He described the days as scorchers, but, to his surprise, summer Athens “pleased him more than ever” (letter to his wife on June 28, 1910). “This is a great town in summer. I have just been down in front of the Zappeion listening to an open air vaudeville and drinking coffee and masticha… I am learning how the Athenians live. The days are so hot that life at night must be busy.” A few evenings later he was back at the square watching moving pictures.

“When I left the square this evening the seats were still well filled and only half the program of music and moving pictures finished. I wish we had that sort of thing [in the] summers. The crowded square under a clear sky is great. Why hustle so much? These people do things as well as we and without half the hustle and worry… Oh I like the life all right. My sole sorrow is being alone.“

To cope with the day’s heat, Weller adopted the afternoon nap. “Since luncheon I have been asleep for an hour. I have taken to undressing and going to bed just as at night. One is up late nights and needs the day’s sleep” as he explained in another letter (July 7, 1910). In Horton’s Modern Athens, “everybody, except the bustling foreigner, respected the noon-day nap in Athens” (p.9)—proof that by 1910 Weller was turning into a Greek.

The Constitution Square as illustrated by Corwin Knapp Liston. Source: George Horton, Modern Athens (1901).

ATHENS, THE LAND OF PURPLE SUNSETS

Horton’s summer Athens was also the land of purple sunsets (p. 90). “It will pay us to keep our eyes fixed upon the slopes of Hymettus just as the sun is going down. During the few moments immediately following the disappearance of that luminary the sides of the mountain are bathed in a deep, soft, yet quite vivid violet hue. This is the most transporting, most poetic spectacle on earth—the far-famed transfiguration of Hymettus… The poet or the dreamer who has looked but once upon that violet glow is homesick for it ever after,” according to Horton (p. 27).

On July 12, 1910, Weller experienced his own Attic sunset “sitting before the west end of the Parthenon watching the sun go down—with my back to it.” The light on the building is wonderful. I like to dream here at sunset and forget for a time the problems that the Parthenon presents to the archaeologist. There is nothing quite like the crimson light on this building and the mountains beyond for rousing reveries. There. It’s over, and in a moment the whistle of the guard will tell me to go. I will go down to the square and sip a coffee while reading the evening paper. There’s the whistle…”

The Parthenon, 1901. Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Note: The second phrase in my title “A sentimental capital and a resort of scholars” comes from George Horton’s Modern Athens (1901, p. 85).

Wonderful as always! Thank you for this.

I love these early School stories, even on April Fool’s Day. Keep ’em coming, Natalia.

I do too! Good job!

Back in Greece for a month last year, thanks in part to your deeply moving narrative, Natalia, as nostalgia inexorably led to walking this wonderful landscape again. I can again appreciate those purple dusks on Hymettos better than ever. Thank You!

Great story, Natalia! I was especially interested to see the photo of Charles Weller and his “safety bicycle.” Rufus Richardson was also an ardent cyclist and even conducted bicycle-mounted School trips.

[…] Turn of the century Athens. […]

Does anyone know anything about Ruth Weller McCuskey Nelson’s glass plate photography?

Thank you

I am afraid not.

Thank you.

[…] Golf Club (yes, there was a golf club in Athens since the 1900s; I have written about it in “Athens at the Turn of the Century: A Sentimental Capital and a Resort for Scholars“): “the golf course, which is on sand was very wet from a recent rain.” (Sept. 10, 1929). […]