The Forgotten Olympic Exhibition: Georg Alexander Mathéy’s Contribution to the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin.

Posted: August 2, 2022 Filed under: Archival Research, Art History, Biography, Exhibits, History of Archaeology, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism | Tags: Georg Alexander Mathéy, Polyxene Roussopoulos Mathéy, Walter Hege 3 CommentsBY ALEXANDRA KANKELEIT

Alexandra Kankeleit is a German-Greek archaeologist and historian. She has been researching German archaeology in Greece during the Nazi period for several years. Since July 2021 she has been working for the CeMoG (Centrum Modernes Griechenland) at the Freie Universität Berlin, where she will teach a seminar on the 1936 Summer Olympics in the upcoming winter semester. Here she contributes an essay about the German artist Georg Alexander Mathéy (1884-1968), who lived in Greece in the 1930s and whose work was displayed in the Summer Olympics of 1936.

The Badische Landesbibliothek in Karlsruhe (BLB) has held a large part of the estate of painter and writer Georg Alexander Mathéy (1884-1968) since 1993. In 2017, the BLB organized an exhibition, titled Sprachbilder – Bildersprache: Die Künstler Helene Marcarover und Georg Alexander Mathéy, to showcase the works of Mathéy together with those of another artist, the painter and poet Helene Markarova (1904-1992). Both artists, whose work was shaped by the two wars, by migration and alienation, were able through literature to transform images into words, and vice versa. A wonderful accompanying publication provides insights into Mathéy’s life and creative work (Axtmann – Stello 2017).

Trained as an architect in Budapest, Mathéy made his name as an illustrator of numerous books and magazines, achieving commercial success already at a young age. He also designed stamps, textiles, and a Rosenthal coffee service. Two of his stamp designs are still remembered today because of their intense colors and memorable motifs: the “bricklayer” (1919) and the “post horn” (1951). They can be described as classics of German stamp design.

In addition to this modern, highly reductivist formal language, Mathéy also mastered other, more traditional media, primarily in his large-scale watercolors and oil paintings.

I became interested in Mathéy’s largely forgotten contribution to the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin. The starting point is material from the archives of the BLB, which provided new and important information about Mathéy. (I would like to thank the director of the BLB, Julia Hiller von Gaertringen, for her interest and active support in my project. A detailed German version of this article can be found on the BLBlog.) Further information can also be found in an unpublished research paper on Georg Alexander Mathéy, which the designer Ulrike Jänichen completed in 2003 under the direction of Professor Mechthild Lobisch at the Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule in Halle. She kindly made her work available to me.

Recalling a Museum Theft

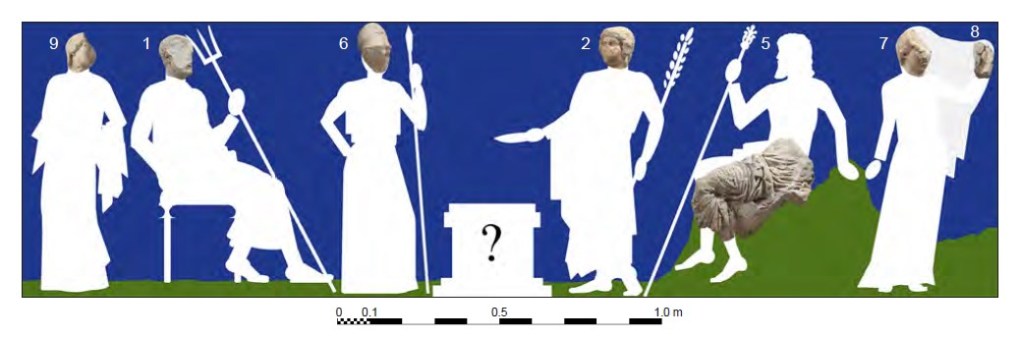

Posted: April 21, 2022 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Art History, Classics, History of Archaeology, Mediterranean Studies, Philhellenism | Tags: Athenian Agora Excavations, Charles H. Morgan, Christine Alexander, Eugene Vanderpool, Homer A. Thompson, Γιάννης Μηλιάδης, John L. Caskey, John Meliades 4 Comments“Sadly, the best candidate for him, the beautifully carved [head] 3, facing right, was stolen from the Agora’s dig house in 1955, while the Stoa of Attalos was under construction.” This sentence caught my attention while reading “Classical Sculpture from the Athenian Agora, Part 2: The Friezes of the Temple of Ares (Temple of Athena Pallenis),” published in Hesperia 88 (2019) by Andrew Stewart and seven co-authors (E. Driscoll, S. Estrin, N. J. Gleason, E. Lawrence, R. Levitan, S. Lloyd-Knauf, and K. Turbeville). Further below in the catalog entry for the head, the exact date of the theft is also mentioned: August 22, 1955.

Stewart et al. refer to a fragmentary male head of high craftsmanship that was found in the Athenian Agora near the northeast corner of the Temple of Ares in 1933. Carved around 430-425 B.C. and identified as Hermes, the small head (H.: 0.147m) is one of forty-nine half-size marble fragments which once decorated the friezes of the Temple of Ares in the Agora (originally the Temple of Athena Pallenis at Pallene). A plan of the Agora with the findspots of the sculptures is included in the Hesperia article, and is also available at https://ascsa.net.

Thefts occur in even the best guarded museums and libraries. Every institution has its own story (or stories) to share or hide. And at least some thefts are committed by those who have “hands-on” access to the collections. A recent example was the return of two valuable journals of Charles Darwin, which were stolen two decades ago from the library of Cambridge University. Others remain lost–the paintings stolen from the Isabella Gardner Museum in Boston in 1990, or the Telephus head, an original by Skopas, removed from the Tegea Museum in 1992.

But back to the little head of Hermes that was inventoried as S 305. I was curious to discover more about its theft. A search in the Archives of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or the School hereafter) yielded considerable information about the event and its aftermath.

Read the rest of this entry »The Cretan Idyll of Harriet Boyd and Charles Henry Hawes

Posted: February 12, 2022 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Art History, Biography, Classics, Crete, Greek Folklore, History of Archaeology, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism, Women's Studies | Tags: Charles Henry Hawes, Crete, Harriet Ann Boyd 6 CommentsBY CURTIS RUNNELS – PRISCILLA MURRAY

Curtis Runnels, Professor of Archaeology at Boston University and an expert in Palaeolithic archaeology in Greece, and his wife Priscilla Murray, an anthropologist and Classical archaeologist, here contribute to From the Archivist’s Notebook a story about their purchase of a sketchbook from the early 20th century with watercolors depicting places and people on Crete.

We visited an antiquarian bookfair in Concord, New Hampshire, about twelve years ago and a booth belonging to a dealer from Vermont, who specialized in original artwork, caught our eye. Sorting through piles of miscellaneous materials, we found a few things relating to Greece, and a small (8 by 4 inches; 20 x 10 cm) artist’s sketchbook grabbed our attention. It was displayed on a table opened to a watercolor view that seemed familiar. Surely it was the entrance to the harbor at Herakleion on Crete! And indeed, penciled in one corner was the inscription “Candia,” the older name for the city which both confirmed the identification and provided a clue that the sketchbook, as dealers in antiques like to say, “had some age.” There were other artworks in the sketchbook that are dated to April 1905, and still others with various dates in 1915, and one dated to 1916. The artwork from 1905 was the most interesting for us. Turning the pages of the sketchbook we saw line drawings of dancers at Knossos and a man drawing water from a well in Siteia, pastels of houses labeled Knossos and “Sitia, as well as watercolors and line drawings of Mykonos, Ios, and other Cycladic islands, Sounion, and Athens. The unknown artist was interested particularly in the new Minoan finds from Knossos as is evident from the line drawings of wall paintings and artifacts in the “Candia Museum.”

Although there is no artist’s signature, we guessed that the artist must be someone interesting, perhaps even someone we would recognize. After all, how many Americans or British travelers (the fact that the titles are in English is the reason for assuming the nationality of the artist) were sufficiently interested in Knossos and the Minoans to visit Crete in 1905 at a time when there was much unrest on the island? We bought the sketchbook and took it home to do more research.

A PORTRAIT OF A (PAGAN) LADY: MABEL GORDON DUNLAP

Posted: December 11, 2020 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Art History, Biography, History of Archaeology, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism, Serbia, Women's Studies | Tags: Ion Dragoumis, Mabel Dunlap Grouitch 4 CommentsIn 1897 a young American woman announced in the newspapers her return to Chicago after a year in Europe. “Miss Mabel Gordon Dunlap of Michigan Boulevard, who has been in Europe for a year, will sail for home on Wednesday” (Chicago Inter Ocean, August 15, 1897). The same woman had also made an earlier announcement that she was still in London “spending most of her time at the British Museum” (17 July 1897). While in London she printed a handsome pamphlet, titled “A Critical Study of Sculpture and Painting,” that contained information about her as a teacher and a lecturer, and a summary of two art courses that she was “ready to deliver before ladies’ clubs and schools” in the winter: “A Course of Twelve Lectures on the History & Philosophy of Greek Sculpture,” and “A Course of Twelve Lectures of the History of Painting in Italy.” While in England she had attended lectures by Charles Waldstein, Professor of Fine Arts at Cambridge University (and former Director of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens), whom she quoted in her brochure: “There are those who make art, there are those who enjoy art, and there are those who understand art.” Dunlap’s courses, fully illustrated with stereopticon views, were designed to help people understand art.

Is this Julia Ward Howe?

Posted: June 1, 2020 Filed under: Archival Research, Art History, Biography, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism, Women's Studies | Tags: Anne Hall, Julia Ward Howe, Samuel Gridley Howe 4 CommentsBY CURTIS RUNNELS – PRISCILLA MURRAY

Curtis Runnels, Professor of Archaeology at Boston University and an expert in Palaeolithic archaeology in Greece, and his wife Priscilla Murray, an anthropologist and Classical archaeologist, here contribute to From the Archivist’s Notebook a story about the purchase of a miniature portrait of an elegant, young woman in an antique fair, their research to identify both the subject of the portrait and its creator, and, finally, their thrilling discovery.

Even from a distance, the small portrait of a beautiful young woman had a commanding presence. We bought the miniature watercolor on ivory (less than 10 by 8 cm) at an antique fair in Holliston, a town near Boston, Massachusetts, because the sitter was dressed a la Gréque with a Greek column in the background. The quality of the painting, which points to a very accomplished miniaturist, together with the appearance and accoutrements of the subject, suggest that the painting was an important commission by a socially prominent person. We loved the painting, and of course, we were intensely interested in the identity of the young woman.