“Who Doesn’t Belong Anywhere, Has a Chance Everywhere”: The Formative Years of Emilie Haspels in Greece.

Posted: November 1, 2020 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, History of Archaeology, Philhellenism, Women's Studies | Tags: Emilie Haspels, Francis H. Bacon, John Beazley, Wilhelm Dörpfeld, Winifred Lamb 3 CommentsBY FILIZ SONGU

Filiz Songu studied archaeology in Izmir and Ankara. As an independent scholar, she works for the Allard Pierson in Amsterdam and is a staff member of the Plakari Archaeological Project in Southern Euboia. She just completed her biographical research into the life and work of Dutch archaeologist Emilie Haspels. In her contribution to From the Archivist’s Notebook, she discusses Haspels’s early formative years in pre-WW II Greece, and the challenges she and other women archaeologists of her time met in a male-dominated field. Since Haspels worked with many foreign archaeological schools in Greece, Songu’s essay is literally a “Who’s Who” of foreign archaeology in interwar Greece.

Caroline Henriëtte Emilie Haspels (1894–1980) was a prominent classical archaeologist in the Netherlands in the decades after WW II. She was the first female professor of Archaeology at the University of Amsterdam and the first female director of the Allard Pierson Museum. Most scholars know her from her study The Highlands of Phrygia. Sites and Monuments (1971), which is still a reference work on the rock-cut monuments in the Phrygian Highlands in central Turkey. For another group of academicians, Emilie Haspels is known for her other classic publication, Attic Black-Figured Lekythoi (1936).

One may wonder what the connection is between these two widely differing fields of specialization. When I started my biographical research into the life and work of Emilie Haspels, my original focus was on her pioneering fieldwork in Turkey. However, when I dug deeper into her personal documents, I discovered more about other significant periods of her life. Her archive provided glimpses of, for instance, her time in Shanghai in 1925–26, and her enforced stay in Istanbul during WW II. It shows how the twists and turns of history affected both her private and her academic life. Key to understanding her archaeological carrier is what I like to call her “Greek period.” The years she spent in Greece in the 1930s doing her PhD research appear to be her formative years as an archaeologist. With the field experience and special skills she acquired in Greece, she paved the way, perhaps unconsciously, to the Phrygian Highlands, which became her life’s work. It was also during her Greek period that she started to build up a wide international network. Haspels’s personal documents and correspondence in various Dutch archives provide complementary information about the scholarly community in pre-WW II Athens and connect with the writings in Natalia Vogeikoff-Brogan’s blog.

Becoming an Archaeologist

Haspels’s Greek period started in the spring of 1929 with her arrival in Athens as a foreign member of the French School. A little about her academic background may be useful here. Haspels had studied Classics at the University of Amsterdam between 1912 and 1923. She minored in Ancient History and Classical Archaeology, attending Jan Six’s classes.

“Mr. Lo”: The First Chinese Student at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1933.

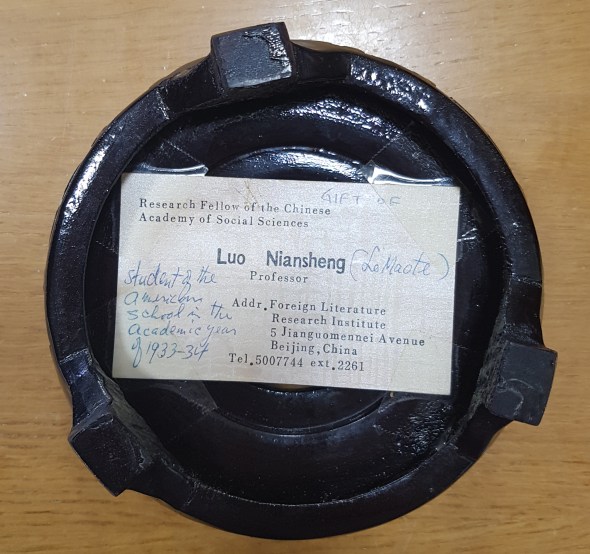

Posted: October 4, 2020 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Classics, History of Archaeology, Philhellenism | Tags: Edward D. Perry, Luo Niansheng, Mao-Te Lo, Richard H. Howland, Thomas Means 5 CommentsIn the late 1990s, a few years after I was appointed Archivist of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or the School), Robert (Bob) A. Bridges, the Secretary of the School, brought to the Archives a Chinese metallic vase to be saved because it was part of our institutional history. Bob said that the bearer of the gift was a former student of the School from the 1930s, who had visited Greece and the School in the 1980s. Underneath the vase, Bob had pasted the donor’s professional card to make sure that his identity was not lost. The print on the card read: Luo Niansheng, Professor [and] Research Fellow of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences; and scribbled on it: Lo Maote student of the American School in the academic year of 1933-1934.

The School’s Directory in Louis E. Lord’s History of the American School of Classical Studies (1947) lists the following information for “Mr. Lo”:

LO, MAO TE 1933-1934 – Tern., Chinese Educational Mission, 1360 Madison Street, Washington, D. C, or 317 College Avenue, Ithaca, New York; Per., Yu-Tai-Huan Company, Lo-Chwan-Tsing, Ese-Chung-Hsien, Sze-Chuan, China. A.B., Ohio State University, 1931.

Is this Julia Ward Howe?

Posted: June 1, 2020 Filed under: Archival Research, Art History, Biography, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism, Women's Studies | Tags: Anne Hall, Julia Ward Howe, Samuel Gridley Howe 4 CommentsBY CURTIS RUNNELS – PRISCILLA MURRAY

Curtis Runnels, Professor of Archaeology at Boston University and an expert in Palaeolithic archaeology in Greece, and his wife Priscilla Murray, an anthropologist and Classical archaeologist, here contribute to From the Archivist’s Notebook a story about the purchase of a miniature portrait of an elegant, young woman in an antique fair, their research to identify both the subject of the portrait and its creator, and, finally, their thrilling discovery.

Even from a distance, the small portrait of a beautiful young woman had a commanding presence. We bought the miniature watercolor on ivory (less than 10 by 8 cm) at an antique fair in Holliston, a town near Boston, Massachusetts, because the sitter was dressed a la Gréque with a Greek column in the background. The quality of the painting, which points to a very accomplished miniaturist, together with the appearance and accoutrements of the subject, suggest that the painting was an important commission by a socially prominent person. We loved the painting, and of course, we were intensely interested in the identity of the young woman.

Forgotten Friend of Skyros: Hazel D. Hansen (Part II)

Posted: May 14, 2020 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Classics, Greek Folklore, History of Archaeology, Philhellenism, Women's Studies | Tags: Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway, Francis Bertram Welch, Hazel D. Hansen, Oscar Broneer, Stanford University 2 CommentsAs a young woman, Hazel Dorothy Hansen broke several glass ceilings. From a humble background –her father was a foundryman—she was admitted to Stanford University in 1916, at a time when the institution had severely limited the admission of women. In 1904, Mrs. Stanford became afraid of the increasing number of women enrolling at Stanford (by 1899 reaching almost 40% of the student population) and implemented a quota that restricted their numbers at the undergraduate level: for every woman at Stanford, there had to be three men. (See Sam Scott, “Why Jane Stanford Limited Women’s Enrollment to 500,” Stanford Magazine, Aug. 22, 2018.). Fortunately for a girl of modest means, Stanford remained tuition-free until 1920.

She broke the glass ceiling again when she chose a prehistoric topic for her dissertation (“Early Civilization in Thessaly”) that also required extensive surveying for sites on the Greek periphery. In the 1920’s female graduate students at the American School had limited options when it came to field research. Apart from Alice Leslie Walker, who had been entrusted with the publication of its Neolithic pottery, Corinth remained a male domain, with Bert Hodge Hill and Carl W. Blegen controlling access to, and publication of, archaeological material. Hazel would have needed either to finance her own excavation, as Hetty Goldman and Walker had done in the 1910s, or to write an art history thesis based on material in museums. It was not until David R. Robinson began excavations at Olynthus and Edward Capps spearheaded the Athenian Agora Excavations that women were allowed to participate in the publication of (secondary) excavation material.

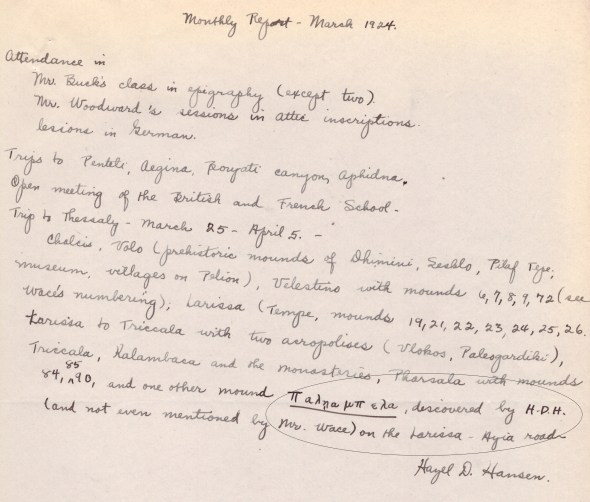

Hansen’s monthly report (March 1924) to the School’s Director, where she lists her trips, and also proudly claims that she discovered the prehistoric site of Μαγούλα Παλιάμπελα (“and not even mentioned by Mr. Wace”). ASCSA Archives, AdmRec 108/1, folder 5.

An Unconventional Union: “Mr. and Mrs. George Kosmopoulos”

Posted: March 14, 2020 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, History of Archaeology, Mediterranean Studies, Philhellenism, Women's Studies | Tags: Agnes Ethel Conway, Alice Leslie Walker Kosmopoulos, Angelis Kosmopoulos, Arcadia, George Kosmopoulos, John C. Lavezzi, Leicester B. Holland, Magouliana 14 Comments“That giant Arcadian mountaineer, servant, foreman and friend, proved the hero of the week-end. I never saw any one more dignified, grave and competent, and as he came from the heights of Arcadia, his physique was impressive, unlike that of the usual wiry little Greek. He brought us tea in the Museum, which we ate sitting among baskets of pottery and fragments of sculpture” (Conway 1917, p. 37).

The passage above comes from Agnes Ethel Conway’s book, A Ride through the Balkans: On Classic Ground with a Camera, and refers to George (Γεώργιος) Kosmopoulos, the son of Angelis (Αγγελής) –both skilled and highly valued foremen of American and German excavations in Greece in the late 19th and early 20th century.[1] Published in 1917, the book is an account of a journey that two young, English women, Conway and her friend Evelyn Radford, made in the Balkan Peninsula in the spring of 1914 as students of the British School of Archaeology. One of their first excursions, while still living in Athens, was to the nearby site of Corinth, where the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or the School) had been digging since 1895.

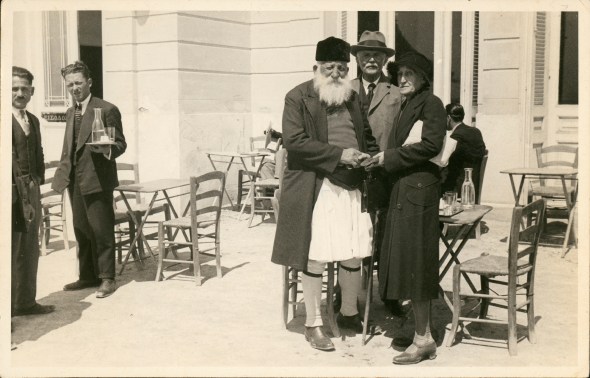

Angelis Kosmopoulos, clad in a fustanella, with German archaeologist William Dörpfeld and Mrs. Dörpfeld (?), Tripolis 1937. ASCSA Archives, Richard H. Howland Papers.

Evelyn, “had a friend, an archaeologist, who was taking part in the excavations at Corinth, and invited us to come to her for the week-end.” The friend was no other than Alice Leslie Walker (1885-1954), a graduate of Vassar College (Class of 1906) who had already acquired the reputation of a seasoned excavator, having co-directed with Hetty Goldman the excavations of ancient Halae in Boeotia in 1911-1913. Upon arriving at Corinth the two women went to the excavations, where “our friend had just dug up the oldest piece of pottery ever found in the Peloponnese,” described Conway in her book (p. 36). Eighty years later, John C. Lavezzi, writing a biographical essay about Walker (for Brown University’s online project, Breaking Ground: Women in Old World Archaeology) would describe her discovery “as the largest and probably still the most significant deposit of Early Neolithic pottery from Corinth.” (Also check the comments that John Lavezzi and others added to the post since it went online.)

Alice Leslie Walker, 1906. Source: Vassarion… Vassar College, 1906.

The following day the three women and George drove with a “sousta” (a kind of carriage) to ancient Sicyon to see the ancient theater. On the way back they “persuaded George to sing to us… His grandfather had been in close attendance to Kolokotronis and his pride in the songs was splendid to see. He was very anxious that we should understand all the words in the songs, and assured us over and over again that the circumstances were really historical… George had the remains of a fine voice, and to hear a patriot, full of pride in his songs, sing them in his own country, in the moonlight, was an experience worth having” (Conway 1917, pp. 39-40). Read the rest of this entry »