A Journey in the Mediterranean on the Eve of the Great War, 1914.

Posted: November 20, 2022 Filed under: Archival Research, Biography, History of Archaeology, Mediterranean Studies, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism, Uncategorized | Tags: Alice Calvert Bacon, Dardanelles, Delphi, Francis H. Bacon, Great War, Guy B. Pears, Julia Dragoumis, Olympia, Poros Island 6 CommentsOn July 4th, 1914, Francis Henry Bacon (1856-1940) and his wife Alice (née Calvert) departed from New York aboard the S.S. Kaiser Frantz Joseph (the ship would be renamed the President Wilson shortly thereafter). The Dardanelles were their destination, where the Calvert family owned an estate, as well as a farm in nearby Thymbra. This is where Bacon had first met Alice in 1883, when the members of the Assos Excavations received an invitation to dine with Alice’s uncle, Frank Calvert (1828-1908). An amateur archaeologist, Calvert had conducted several excavations in the Dardanelles. Perhaps more importantly, he suggested that Heinrich Schliemann (1822-1890) look for Troy at the site of Hissarlik, not far from Thymbra, in the late 1860s. The Calverts were English expatriates long established in the Dardanelles, who made a living trading commodities with the benefit of consular posts.

The time was not good, however, to travel to Europe and especially to the Balkans and Turkey. Just a few days before, on June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife had been assassinated in Sarajevo. His death sparked a series of events that led Austria with the support of Germany to declare war on Serbia a month later. Within a week, the great powers of Europe were forced to ally with or against the main belligerents. Greece tried to remain neutral until 1917 (in no small part because the Greek King was married to the Kaiser’s sister and thus sympathetic to the German side), but the Ottoman Empire openly supported the Germans.

Retracing his Steps

Bacon, a graduate of M.I.T (1876), first traveled to Greece in 1878, before the American School of Classical Studies was even founded. In 1881 he would join, as chief architect, the Archaeological Institute of America’s excavations at Assos in Western Turkey. Following Assos, Bacon pursued a successful career in interior design on the East Coast of America about which I have written before (Francis H. Bacon: Bearer of Precious Gifts from the Dardanelles). He is also credited with the design of the Shrine of the Declaration of Independence in the Library of Congress. Because of Alice’s attachment to the Calvert house in the Dardanelles, the Bacons frequently crossed the Atlantic. Occasionally, Francis would make a stop in Greece to retrace his steps.

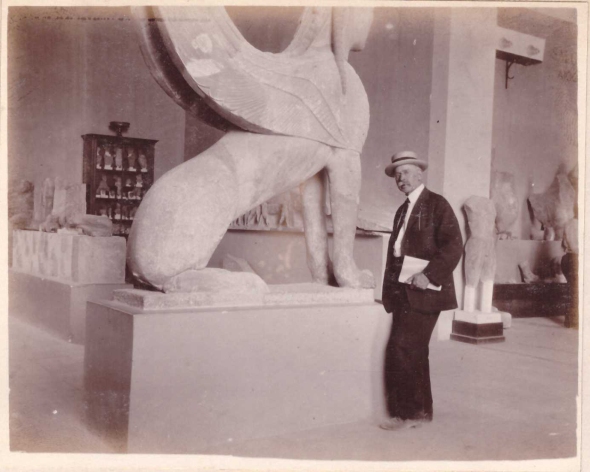

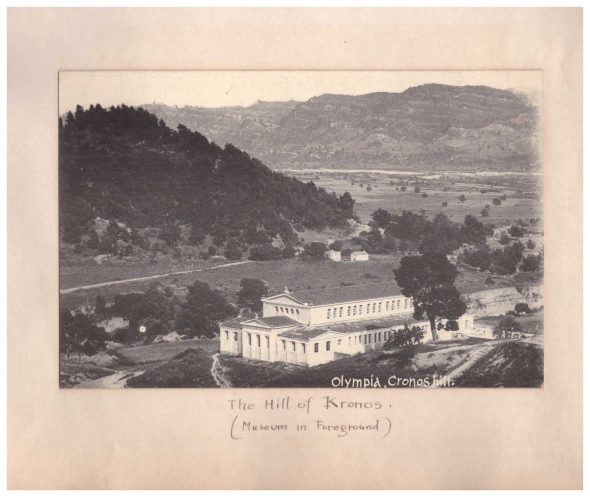

After several stops including the Azores, Algiers, and Naples, the Bacons finally reached Patras on July 16th, where the couple parted. Alice continued on another steamer to the Dardanelles, while Francis planned to spend a week in Greece, starting from Olympia. “Splendid Victory of Paionios, and then the lovely, beautifully finished Hermes of Praxiteles – about the only authentic ancient masterpiece in the world,” Bacon scribbled in his notebook. The authenticity of the statue –whether it was a 4th century B.C. original or a fine Roman copy- had not yet been challenged.

From Patras, Bacon took a little steamer to Itea. At Delphi he was much impressed by the restoration of the Athenian Treasury, which the French had completed a few years earlier (1903-1906.) He only wished that “they had restored the acroteria, two horses with naked riders prancing off the corners of the pediment.” Bacon, an ardent photographer, did not miss a chance to capture monuments and landscape, as well as to experiment with interior photography, which was exceptionally difficult at the time. “Back to the Museum where the Ephor Contoleon is very obliging and invited us to photo and measure anything we like.” I cherish Bacon’s interior photos because we catch glimpses of the old museum displays. To him we owe a partial view of the old Delphi Museum, built in 1903, and several charming photos of the local children who had befriended one of his fellow travelers. See slideshow below.

After two days at Delphi, Bacon headed off for Athens. “Start at Itea at 5 A.M. Steamer at 6:30 for Corinth Canal and Piraeus. There has been a landslide in the canal and the little steamer almost climbs over a pile of clay and earth in the narrow channel. Reach Piraeus at 4 P.M. Drive to Athens over the dusty road. Go to Hotel Minerva where I spent winter in 1883, now rather dirty and forlorn.”

(The Hotel Minerva located at Stadiou 5 operated until 1991. When Bacon first stayed in it in 1883, it was known as Αι Αθήναι. For more information and a photo of the hotel, check out the site of the Greek Literary and Historical Archive.)

Read the rest of this entry »