A Journey in the Mediterranean on the Eve of the Great War, 1914.

Posted: November 20, 2022 Filed under: Archival Research, Biography, History of Archaeology, Mediterranean Studies, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism, Uncategorized | Tags: Alice Calvert Bacon, Dardanelles, Delphi, Francis H. Bacon, Great War, Guy B. Pears, Julia Dragoumis, Olympia, Poros Island 6 CommentsOn July 4th, 1914, Francis Henry Bacon (1856-1940) and his wife Alice (née Calvert) departed from New York aboard the S.S. Kaiser Frantz Joseph (the ship would be renamed the President Wilson shortly thereafter). The Dardanelles were their destination, where the Calvert family owned an estate, as well as a farm in nearby Thymbra. This is where Bacon had first met Alice in 1883, when the members of the Assos Excavations received an invitation to dine with Alice’s uncle, Frank Calvert (1828-1908). An amateur archaeologist, Calvert had conducted several excavations in the Dardanelles. Perhaps more importantly, he suggested that Heinrich Schliemann (1822-1890) look for Troy at the site of Hissarlik, not far from Thymbra, in the late 1860s. The Calverts were English expatriates long established in the Dardanelles, who made a living trading commodities with the benefit of consular posts.

The time was not good, however, to travel to Europe and especially to the Balkans and Turkey. Just a few days before, on June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife had been assassinated in Sarajevo. His death sparked a series of events that led Austria with the support of Germany to declare war on Serbia a month later. Within a week, the great powers of Europe were forced to ally with or against the main belligerents. Greece tried to remain neutral until 1917 (in no small part because the Greek King was married to the Kaiser’s sister and thus sympathetic to the German side), but the Ottoman Empire openly supported the Germans.

Retracing his Steps

Bacon, a graduate of M.I.T (1876), first traveled to Greece in 1878, before the American School of Classical Studies was even founded. In 1881 he would join, as chief architect, the Archaeological Institute of America’s excavations at Assos in Western Turkey. Following Assos, Bacon pursued a successful career in interior design on the East Coast of America about which I have written before (Francis H. Bacon: Bearer of Precious Gifts from the Dardanelles). He is also credited with the design of the Shrine of the Declaration of Independence in the Library of Congress. Because of Alice’s attachment to the Calvert house in the Dardanelles, the Bacons frequently crossed the Atlantic. Occasionally, Francis would make a stop in Greece to retrace his steps.

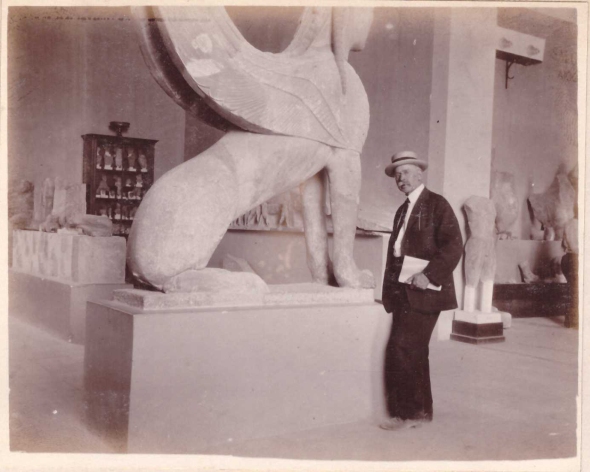

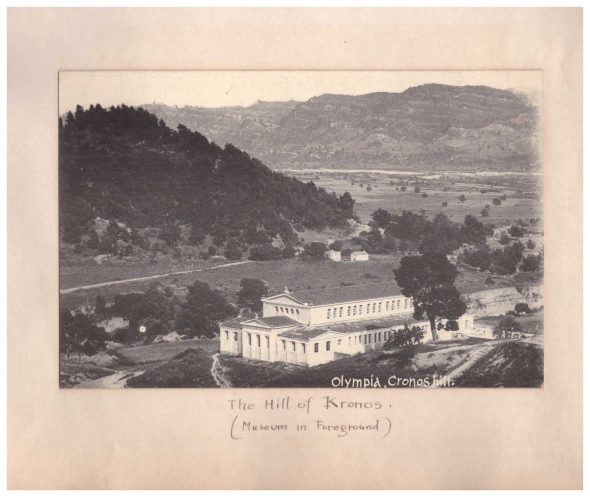

After several stops including the Azores, Algiers, and Naples, the Bacons finally reached Patras on July 16th, where the couple parted. Alice continued on another steamer to the Dardanelles, while Francis planned to spend a week in Greece, starting from Olympia. “Splendid Victory of Paionios, and then the lovely, beautifully finished Hermes of Praxiteles – about the only authentic ancient masterpiece in the world,” Bacon scribbled in his notebook. The authenticity of the statue –whether it was a 4th century B.C. original or a fine Roman copy- had not yet been challenged.

From Patras, Bacon took a little steamer to Itea. At Delphi he was much impressed by the restoration of the Athenian Treasury, which the French had completed a few years earlier (1903-1906.) He only wished that “they had restored the acroteria, two horses with naked riders prancing off the corners of the pediment.” Bacon, an ardent photographer, did not miss a chance to capture monuments and landscape, as well as to experiment with interior photography, which was exceptionally difficult at the time. “Back to the Museum where the Ephor Contoleon is very obliging and invited us to photo and measure anything we like.” I cherish Bacon’s interior photos because we catch glimpses of the old museum displays. To him we owe a partial view of the old Delphi Museum, built in 1903, and several charming photos of the local children who had befriended one of his fellow travelers. See slideshow below.

After two days at Delphi, Bacon headed off for Athens. “Start at Itea at 5 A.M. Steamer at 6:30 for Corinth Canal and Piraeus. There has been a landslide in the canal and the little steamer almost climbs over a pile of clay and earth in the narrow channel. Reach Piraeus at 4 P.M. Drive to Athens over the dusty road. Go to Hotel Minerva where I spent winter in 1883, now rather dirty and forlorn.”

(The Hotel Minerva located at Stadiou 5 operated until 1991. When Bacon first stayed in it in 1883, it was known as Αι Αθήναι. For more information and a photo of the hotel, check out the site of the Greek Literary and Historical Archive.)

Read the rest of this entry »The American Dream to Excavate Delphi or How the Oracle Vexed the Americans (1879-1891)

Posted: October 2, 2014 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Classics, History of Archaeology, Modern Greek History | Tags: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Archaeological Institute of America, École française d’Athènes, Charilaos Trikoupis, Charles Eliot Norton, Charles Jean Tristan de Montholon, Charles Waldstein, Delphi, Paul Foucart, Pierre Amandry, Stephanos Dragoumis, Walker Fearn, Zante currants 5 CommentsThe story of how the French secured the excavation of Delphi has been told before. Pierre Amandry published an exemplary account (“Fouilles de Delphes et raisins de Corinthe”) of the negotiations between the French, Greeks, and Americans in La redécouverte de Delphes (1992). His work drew heavily on material in the archives of the French ministries of Public Instruction and Foreign Affairs and L’ Academie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres to paint a detailed picture of the French side of the story. His account of the American side is much shorter because Amandry only had access to a handful of documents published in the History of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1882-1942 (1947, pp. 58-62). The author of that volume, Louis Lord, included four letters either addressed to or written by Charles Eliot Norton, the President of the Archaeological Institute of America (AIA). Norton was not only the founding spirit of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA) but also the driving force behind the Institute’s unsuccessful campaign to dig at Delphi. In a brief essay from Excavating Our Past (2002), Phoebe Sheftel presented more records from the archives of the AIA that shed further light on the American side of the Delphi story without, however, making reference to the rich archival resources that Amandry had published in his long article. Sheftel’s story about Delphi is “the story that Norton wanted told” (Sheftel 2002, p. 106). Read the rest of this entry »

Revisiting George Cram Cook and Other Delphic Surprises

Posted: October 15, 2013 Filed under: Archaeology, Classics | Tags: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Delphi, Elias Venezis, George Cram Cook, Judith Binder, Nilla Cook, Richard Mark Hillary, Susan Glaspell, Wolfgang Binder 8 CommentsBack in August, when I wrote about the unusual life of George Cram Cook and his death and burial at Delphi, I promised to add a photo of his grave. Artemis Leontis of Michigan University kindly sent me her own photos of Cook’s and Eva Palmer’s tombs at Delphi, but I hesitated to post them because I felt that I had to visit Cook’s grave myself. Moreover, as an archaeologist, I was curious to examine the ancient block that had been used for his headstone. Susan Glaspell in The Road to the Temple described it as “one of the great fallen stones from the Temple of Apollo” (1926, p. 343). But by the time Elias Venezis referred to Cook’s grave in his American Earth, the block had assumed the shape of a column “συντροφευμένος από μια κολόνα του Ιερού των Δελφών” (1955 [1977], 301). Was it a block or a column drum?

On September 24, Tom Brogan and I drove to Delphi to hear the papers of Tom Levy and his team at a conference on virtual reality in archaeology. Before going to the conference center, we made a brief stop at the local cemetery, which is located above modern village near the southwest edge of the ancient site. Several foreigners are buried in the northwest corner of the cemetery. It wasn’t hard to locate Cook’s grave, two burials to the right of Eva Palmer Sikelianou’s. With a broom that I borrowed from a nearby grave, I cleaned the surface of the marble plaque and revealed this inscription: Read the rest of this entry »

“Going Native”: The Unusual Case of George Cram Cook

Posted: August 1, 2013 Filed under: Archaeology, Philhellenism | Tags: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Angelos Sikelianos, Delphi, Dorothy Burr Thompson, Elias Venezis, Eva Palmer, George Cram Cook, John Anton, Kostis Kourelis, Leandros Palamas, Susan Glaspell 3 CommentsIn The Road to Temple, a biography of George Cram Cook, his wife, author Susan Glaspell wrote: “He liked the shepherd’s clothes, worn also by the peasants. A grey or black tunic, white tights of beautiful wool from the sheep of Parnassos, spun and woven by the women, heavy half-shoes crowned with poms-poms, and a little black skull cap.” Cook had adopted this attire when he decided to move to Greece in 1922 and make Delphi and Mount Parnassus his new home. By January 1924, Cook had died of glanders (contracted from his pet dog) and was buried at Delphi, a column drum from the Temple of Apollo marking his grave. Glaspell published The Road to Temple only two years later.

I did not know who George Cram Cook (nicknamed “Jig”) was until a few years ago. While reading the diaries of archaeologist Dorothy Burr Thompson, I discovered by happenstance the following entry for October 15, 1923: “At supper G. Cram Cook, husband of Susan Glaspell, appeared in Greek costume in the restaurant –looking handsome and ridiculous. He is writing four plays on modern Greece…” There is one more entry in Thompson’s diary about Cook. On January 16, 1924 she mentions his death: “G. Cram Cook died of hydrophobia in Delphi – poor man, his four plays unfinished.” One senses some slight sarcasm in her remark. Read the rest of this entry »