On Communism and Hellenism: An Archaeologist’s Perspective

Posted: March 1, 2016 Filed under: American Studies, Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, History, History of Archaeology, Intellectual HIstory, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism | Tags: Alison Frantz, American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Carl W. Blegen, Communism, Donald C. McKay, Hellenism 3 CommentsPosted by Despina Lalaki

Despina Lalaki holds a PhD in Historical Sociology from the New School university while she currently teaches at the The New York City College of Technology-CUNY. The essay she contributed to ‘From the Archivist’s Notebook’ is largely an excerpt from her article “On the Social Construction of Hellenism: Cold War Narratives of Modernity, Development, and Democracy for Greece,” in The Journal of Historical Sociology, 25:4, 2012, pp. 552-577. Her essay draws inspiration from an unpublished manuscript by archaeologist Carl W. Blegen, titled “The United States and Greece” and written in 1946-1948.

Carl W. Blegen (1887-1971) is one of the most eminent archaeologists of the Greek Bronze Age. Nevertheless, he intimately knew Modern Greece, too. In 1910, at the age of twenty-three, he first visited the country as a student of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (hereafter ASCSA), and by the time of his death in 1971 he had made Greece his home and his final resting place, having experienced first hand the land and its people in the most troublesome moments of their modern history. In 1918, for instance, he participated in the Greek Commission of the American Red Cross, assisting with the repatriation and rehabilitation of thousands of refugees who during the war had been held as prisoners in Bulgaria. During WWII, he was recruited by the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) to head the Greek desk of the Foreign Nationalities Branch (FNB) in Washington D.C., which was following European and Mediterranean ethnic groups living in the United States and recording their knowledge of political trends and conditions affecting their native lands.

J. W. Foster (left) and Carl W. Blegen (right) standing at the headquarters of the Allied Mission for Observing the Greek Elections (AMFOGE), 1946. Photo by Nat Farbman. The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images/Ideal Image.

As a new world state of affairs was coming into place—a post-war, post-colonial, post-modern world—scientists and intellectuals would play a central role in articulating its new shape and form. The resistance movement in Greece, as in other places in Europe, would take on social and political dimensions that constituted a potential threat to the social order that the victors of the war had envisioned, and now a new war for the hearts and minds of those liberated would be set in motion. In 1945 Blegen, while still in the employ of the FNB, was invited by Harvard University Press to offer once again his services. Roger Scaife, the director of the Press, had projected a series of books on various parts of the world written with reference to their importance in the foreign relations of the United States, and Donald C. McKay, professor of History at Harvard and head of Mediterranean Research and Analysis during the war, was called to serve as associate editor. McKay, who evoked in his letters his earlier harmonious collaboration with Blegen in Washington D.C., and the high regard in which he was held as an authority both in Ancient and Modern Greece, succinctly explained the objectives of the project and outlined an ambitious plan, which envisioned the publication of more than twenty-three volumes in a two-year period:

“The books will deal in some cases with individual countries (the Soviet Union, France, Germany), in others with regions (Southeast Asia, the Caribbean countries). They will seek to make the average intelligent American reader conscious of the character of these countries (geography, people, government, economy), with the great changes which have in most cases been affected by the war, with the character of our relations with them in the past, and above all with the problems which we shall have to face in our relations with them in the immediate and near future” (Carl W. Blegen Papers, Box 25, folder 3)

In the company of some very distinguished scholars, such as John Fairbank, Arthur P. Whitaker, and Ephraim A. Speiser, Blegen would take up the task. However, within the next four years, and while sharing his time between his duties as Cultural Attaché for the American Embassy in Athens upon his return in 1945, as Director of the ASCSA and as archaeologist, Blegen would not complete the project. He has left us with a good draft of his manuscript though, “The United States and Greece“ (Blegen UM, hereafter), which prescribes the future of Greece by pointing toward its familiar, revered past. Accounting for the post-war American involvement in Greece, Blegen opens his book with a disclaimer:

“… our purpose in coming to the assistance of Greece at this juncture … was not to promote any imperialistic ambitions nor did it represent desires for territorial aggrandizement. But our action was by no means a purely altruistic gesture … It was a definite notice to the other nations of the world that we believe our own vital interests are bound up with the situation in Greece, and that we are determined to defend our own social order and ideals of government and to safeguard the way of life in which we have faith and which, we realize, is being threatened by international forces eager to destroy it… It has become clear that Greece is the object of pressure and attack by international communist totalitarianism which is seeking to expand its domination step by step, first over Europe and then over the world” (Blegen UM, p. 29).

Undoubtedly, Blegen echoes here President Truman’s speech rhetoric which, in a well-known phrase attributed to Senator Arthur H. Vandenberg, meant “to scare hell out of the country.” Truman’s speech in the Congress in March of 1947, and the passionate discussions that followed it in the Congress and the media, composed the picture of a western world under threat of imminent destruction unless this new form of totalitarianism was contained and countered by the civilizing forces of capitalism and democracy.

In the manuscript, Blegen establishes a precedent for this new economic environment by stressing and rather stretching the importance of U.S. trade with Greece in the 1930s and their assistance towards infrastructure development. Most importantly, however, he focuses on the political history of the Greek state, always with an emphasis on the destabilizing communist threat and after establishing some important connections to the part of Greek history with which the American public imagination was already acquainted: classical antiquity.

Extracting from his extensive knowledge as archaeologist and historian, Blegen would draw a direct line between prehistory, classical antiquity, and medieval Byzantine history, concluding that“… there is no doubt that in the people of modern Greece we must recognize the descendants of the ancient Greeks,” directly objecting to ethnic theories such as those advanced early in the 19th century by Jacob Philipp Fallmerayer (1790-1861), who had claimed that “not the slightest drop of undiluted Hellenic blood flows in the veins of the Christian population of present-day Greece.” Blegen’s linear ascending and descending historicity was, of course, deeply rooted in a particular cluster of European understandings about history, space and time, and in the cultural connotations of the Hellenic ideal for European and even American intellectual origins, which were traced back to the ancient Greeks, since, according to Blegen:

“…it was in the fifth and fourth centuries, the classical period par excellence, that democracy was developed and flourished … and to these two centuries belong many of the names most illustrious in history, philosophy, drama, architecture, sculpture, painting, and the other arts. Greek culture, at this point, reached maturity and the beginning of its decline” (Blegen UM, p. 54).

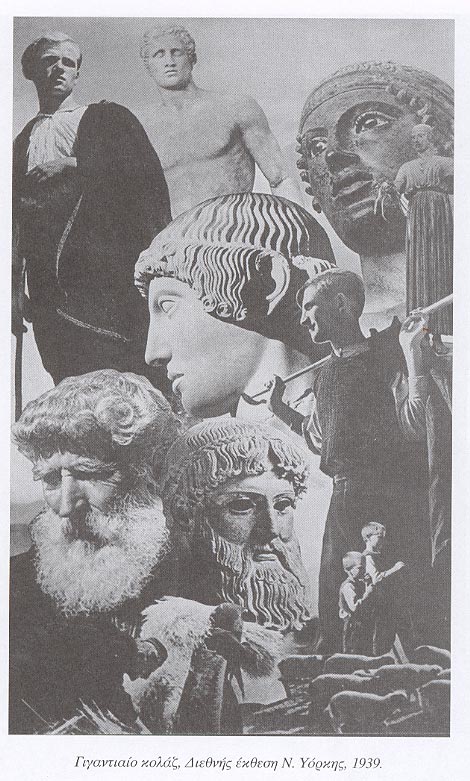

Nelly’s promotional collage for the International Exhibit of 1939 in New York advocating the continuity of the Greek race.

The Greek Zeitgeist and the Communist Philosophy

With a great leap in time, the culmination of this decline would not be difficult for the reader to identify in the next pages with the emergence of communism as a political force in the life of the country, which would constitute a serious threat, if poverty and economic destitution remained unchallenged. In any other case, according always to the author, the Greek character was not susceptible to the core values of the communist ideology and the profile of the communist; “of general intelligence,” which “it sometimes attains to an unusual order… that keen Hellenic preoccupation with telling of all things new is still as intense as it was in the days of St. Paul.” And while explaining the Greek zeitgeist as an unchanging constant throughout the ages, Blegen moves from the Judeo-Christian canon—which the idolatrous Greeks were the first Europeans to explore and engage with in the Athenian Agora, where Paul would first preach to the Athenians—back to Aristotle:

“It shows itself [the Greek alertness of mind] in a lively interest, not to say inquisitiveness, with reference to what is going on about one, and it is particularly concerned with persons and personalities. It leads to what is little short of a passionate interest in politics and political developments, local, domestic, and international. For the Greek pre-eminently fits Aristotle’s definition of man as a “political animal” (Blegen UM, p. 42).

Reassuring his prospective American readers about the deserving character and nature of the Greek people and implicitly eradicating any popular concerns about their dubious ethnic and racial characteristics was Blegen’s main concern. After all, the Immigration Act of 1924, which radically restricted the immigration of Eastern and Southern Europeans to the U.S., out of fear of the ethnic and racial degeneration of the country, was still in place. In addition to the lively intelligence of the modern Greek, Blegen stresses his “highly developed individualism,” “perhaps the most conspicuous of the qualities inherited from his ancient ancestors who invented the concept of democracy.” Intelligent, individualistic, albeit often excessively, and keen to finance and banking, with an “almost universal desire to acquire and hold individual property,” Blegen asserts “the fundamental anti-communist philosophy of the majority of the population. Indeed, in this individualistic and essentially unindustrialized state, the ground is not normally favorable to the sowing of communist seed” (p. 48). The seeds, nevertheless, had found fertile ground in Macedonia and Thrace among the propertyless tobacco workers, the undernourished laborers in the big cities, and among those who harbored resentment “of what they believe[d] to be unjust political discrimination and negligence or incompetence on the part of the government” (p. 48).

The employment of the notion of the “Greek identity” and the ideologism of “Greekness” —embedded in the concept of race and a series of timeless, inalienable idioms of the Greek character as a bulwark against communism—was certainly not Blegen’s invention. This same notion had been taken up by the Greek state, as well as by the Greek liberal intellectuals, to face the labor unrest and the communist ideologisms of internationalism and proletarian solidarity. In fact, the Greek intellectuals found in an idealized and abstract nationism (as opposed to nationalism) of a spiritual and metaphysical kind, the antidote to both the corrupting effects of western modernity and the Marxist historical materialism, which they largely rejected as anti-humanist. Like Blegen, they firmly placed “Greekness” in the Western and European civilizational tradition, advocating for the leading role of Greek culture or “Hellenism” in the revival of humanism.

Blegen does not put his reader at rest. He builds a case for a people whose nature and rich culture should safeguard them in a distinct place among the democratic nations of the world but who, subject to corrupting external powers, are on the verge of collapse under the sheer power of eastern totalitarianism. Blegen’s book is in essence an appeal for a renewal of American philhellenism, which back in the 19th century may not have mobilized the American government to assist the Greek fight against the Ottoman Empire, but did inspire private initiative despite the Monroe Doctrine. Once again, in the name of Greece’s symbolic importance as the cradle of western civilization and, on a more pragmatic level now, on the basis of its strategic significance as the underbelly of western democracy in Southern Europe, the Greek state had to be defended.

American Realpolitik

The book was written in the midst of some of the most extraordinary events in the recent history of Europe. Less than two months after the German troops’ departure from Athens and following the National Liberation Front’s (EAM hereafter) demonstration of December 3, 1944, images of British troops fighting in the streets of Athens against one of the most resilient anti-Nazi movements in Europe caused the rage of the House of Commons, and of the British and American media. Whether the demonstration represented an attempt by EAM to take over power is an issue still fervently debated. The broader role of the USSR in the following years is also a topic not settled in the literature. According to Blegen, the 37-day battle that followed between the British troops, the military of the Greek government and EAM-ELAS, constituted “a carefully laid plan for the seizure of power by the Left,” which the British “were inevitably drawn into … in support of the government, as the legally constituted regime.”

The center of Athens, after the bombing of the city by the British. Photo Gladys Davidson Weinberg, January 1945. Source: ASCSA Archives, Saul and Gladys Weinberg Papers.

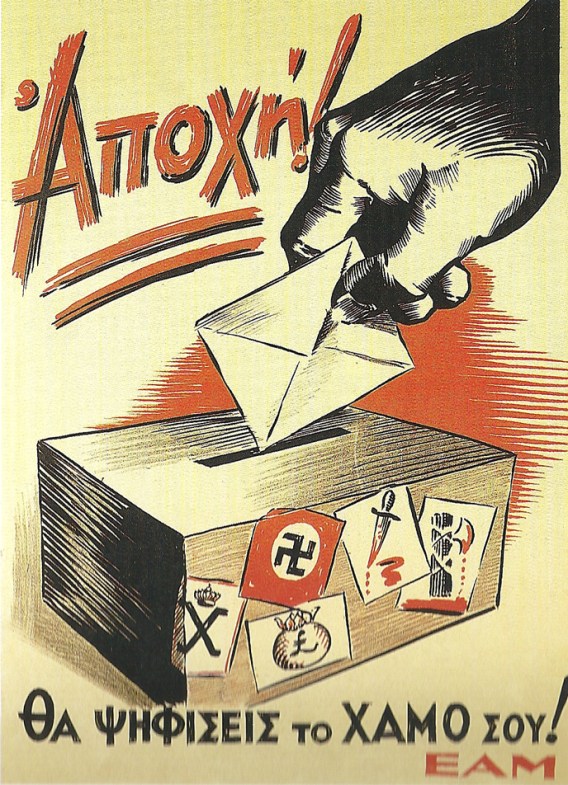

From liberators, the British turned into instigators of a brutal civil war, further inflamed after the elections of March 1946 and the plebiscite in September of the same year, which brought the King back. The issue that had been polarizing Greek society since the early 1920s, and was for years bringing any negotiations between the more moderate political forces to a standstill, was forced upon the Greeks by Winston Churchill’s myopic and colonial nostalgic vision. The American government watched from the sidelines and any criticism, such as that by U.S. Secretary of State Edward R. Stettinius, Jr., was rather subdued and swiftly downplayed.

The topic of the elections and the plebiscite offered to Blegen’s reader further reassurances about democratic procedures and political stability in the country. An Allied Mission for Observing Greek Elections (AMFOGE), comprising British, French and Americans, ensured that “it was unquestionably as fair and honest an election as could be held in a country so recently torn by civil war” (Blegen UM, p. 148). For the plebiscite, which recalled the King to the throne, Blegen was equally cheering and heartening:

“The result unquestionably represented the conviction of the majority of the Greek people that at the time the only possible safeguard against Communist domination lay in rallying about the King and the monarchical form of regime” (Blegen UM, p. 149).

Blegen’s emphasis on democratic processes and further comparisons with Britain and the Scandinavian countries as “some of the most firmly safeguarded and genuine democracies in the world,” were employed to defy America’s aversion to monarchy (pp. 205-206). Alison Frantz (1903-1995), an archaeologist and Blegen’s assistant at the FNB, who had taken part in the AMFOGE and closely followed the events, was less sanguine, however. On August 24, 1946, she wrote to her mother, rather cynically and resignedly:

“The plebiscite is scheduled for a week from today. No one has any illusions about the outcome. It will probably be technically honest, in that the King won’t get 107% of the votes as he did last time, but only the very brave republicans will dare to vote. I’m glad I wasn’t involved in AMFOGE II” (Alison Frantz Papers, Princeton University Library, Box 8, folder 10).

While the emphasis of American policy regarding Europe at large was on reconstruction and economic development, in Greece the problem was primarily political and military. The implementation of the Marshall Plan in Greece was in effect an exercise of Realpolitik which meant to defend the strategic interests of the U.S. in the area. Fearing that the expansion of the Soviet influence in Greece would mean the fall of the whole Middle East, American advisors and administrators brought the whole Greek state apparatus under their direct control, openly maneuvered the Greek government, gave almost absolute control to the military, separating it from the political authority, and tolerated mass executions and the open persecution of the Left by a government which, in the American media, was often compared with the Nazis.

Culture and the Future of Greece

It is only in cultural practices and international scholarship that Blegen will find a fertile ground free of controversy for the cultivation of amiable and cordial relations between the two countries, and will identify the brightest prospects for the future of Greece. He devotes a separate chapter to “Social and Cultural Problems” to explain his faith in culture and in American educational institutions such as the American and the Pierce College in Athens, the Anatolia College and the American Farm School in Thessaloniki, institutions “purely educational in character, patriotic but not propagandistic,” to produce the enlightened leaders of whom the Greek nation was in great need (p. 245). Confident about the strengths of American education and disheartened by the dismal situation of the Greek institutions at the time, Blegen lamented the limited American visas available to Greek students, as well as the lack of foundations interested in the development of close cultural relations between the two countries, not yet assigning much importance to the Fulbright Foundation in Greece, which was just being established with the active assistance of the ASCSA.

In a newly opening international market for national cultural industries, Greece had to offer “the monuments and other physical remains that linger on through the landscape wherever one turns” which, “apart from the biological and linguistic legacy, the classical Greeks have bequeathed to their descendants” (p. 256). Hellenism, which Blegen time and again invokes in his book and which he had scientifically grounded in his archaeological scholarly work, provided the resonance for the country’s ideological orientation but also the means for its economic development. Hellenism, from a force civilisatrice would now be understood as an economic force as well, a cultural commodity in the international tourism and heritage industry:

“For Greece has in abundance what is needed to attract travelers. Islands, seas, narrow coastal plains, and mountains give the scenery an endless variety, ranging from the simple to the majestic; and innumerable historic associations breathe life into every prospect. Incomparable monuments of the past lend distinction to many famous sites still bearing classical names; and museums are filled with treasures of ancient art” (Blegen UM, pp. 230-231).

Not the romantic, classically educated travelers of the 19th century but the “tourists” —a term that Blegen only hesitantly uses, in some cases scribbling “foreign visitors” over it in his manuscript—were destined to be the primary consumers of this new Hellenism in the 20th century. The most recent tourist campaign of the Greek government, more than fifty years later, with slogans such as “Live your myth in Greece,” testifies to the appeal of this latest take on the myth of Hellas.

Classical culture, so often credited as the progenitor of Western civilization, was now subject to the mandates of a new world order which favored the free exchange of cultural, among other, goods, and for that matter Blegen called for some structural transformations: the liberation of the Ministry of Education from its financial servitude to the state and its closer collaboration with the tourism industry, and “some liberalization of the [Archaeological] Service’s attitude toward the export of antiquities,” for as he maintained, “the classical antiquities of Greece, although she naturally has special rights, are in a broad sense not exclusively a national possession of the country in which they happen to be found: they belong to the world, and the whole world is interested in their care (p. 260). The question of to whom a culture belongs or whose heritage it is, whether it is national heritage, world heritage or something else, is being debated and will be debated for some time to come. However what Blegen suggests here, albeit hesitantly and probably inadvertently, is the subjection of an old idea, or better an ideal, to new rules, those of the market—an international market which would appropriate the myth of Hellas in very different ways.

Blegen, clearly in tune with ideas already in circulation at the time, would even recommend a provision for the reconstruction and rehabilitation of museums and monuments as part of the Marshall Plan program for the development of tourism in Greece (ASCSA AdmRec, Box 804/6, folder 11, Memorandum for the Ambassador, August 26, 1948). He would also work hard to include the ASCSA’s project for the reconstruction of the Stoa of Attalos as the Museum of the Ancient Agora in this program (ASCSA AdmRec, Box 318/4, Folder 4). From where Blegen stood, the archaeologists’ and archaeology’s role in the reconstruction of the country was central. The foreign schools of archaeology in Greece produced cultural ambassadors as well as scholars:

“Archaeology seems to offer one of the easiest and most direct channels through which Greece can assure herself a tide of good will, along with moral and material help, from all the enlightened countries of the world” (Blegen UM, p. 257).

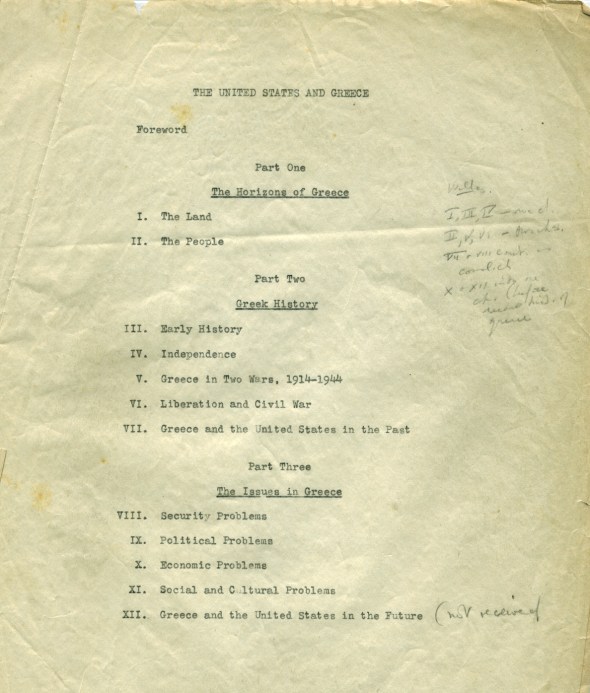

The table of contents in Blegen’s manuscript “The United States and Greece.” Source: ASCSA Archives, Carl W. Blegen Papers

Hellenism as an American Myth

In the aftermath of World War II, the United States, having emerged victorious from its struggle with ultimate evil, had to grapple with its sense of destiny. The myth of the Chosen Nation, a myth which sure enough has fueled the national imagination of other nations as well, was coming back to haunt, if not to dictate, the sense of the U.S.’s responsibility in the opening world arena. As Pulitzer Prize-winning author Lawrence Wright has written: “America had a mission—we thought it was a divine mission—to spread freedom, and freedom meant democracy, and democracy meant capitalism, and all that meant the American way of life.”

Landing on Greece in 1947 as the place to combat communism, the U.S. was acting upon its own values of freedom, individualism, and democracy. To safeguard democracy for the country which had been charged as its first progenitor was the ultimate mission and one which could resonate with anyone who shared this old story. Based on what Richard T. Hughes calls “the myth of the innocent nation”, the U.S. would be thrust upon the world to save it from evil, a battle which continues in our time structured on the same dichotomy, albeit with a different foe. Hence to save Greece was to save the American soul.

Historical “ifs” are not very popular, and it would be hard to speculate on what would have happened with the ideal of Hellas had the communists won the fight. Following the Greek Communist Party’s (KKE) defeat, the prospect of being rehabilitated into the national body gave a new impetus to the intellectuals of the Left to openly subscribe to the logic of historical continuity with classical antiquity, a path which might not have been taken had the civil war ended differently. Blegen’s book would be studied merely as a relic of a vanquished ideal, the carcass of what is no more. In the context, however, of the society that subsequently followed, Blegen’s book can be read as a cultural and ideological roadmap. The book was never published and it can not be studied for its public impact, but read alongside the press of the time—commenting on the correlation between democratic tutelage, economic development and modernization, the invocations of America’s indebtedness to Greece for its gift of civilization and democracy, the subsequent efforts of the Greek government to develop tourism by capitalizing upon the classical past—Blegen’s Hellenism reads as an omen.

One may talk about another instance of “colonization of the ideal,” as Neni Panourgia has succinctly described the European identity formulation process against the cultural prototype of Classical Greece, a process which bears many similarities to subsequent appropriations by the Greek state in its own efforts to articulate an official national narrative. The Americans had wrestled with the ancients as well in their aesthetic and philosophical quests and in their efforts to find the most virtuous political system appropriate for their nation of states, or, as Bernard Bailyn suggests, employed them to window-dress their political thought. However profound or superficial, reflective or opportunistic, insightful or cursory, the American post-war engagement with Hellenism drew from and capitalized upon the indisputable prestige of the ideal and propelled it into the future, providing the subtext for Greece’s place within the post-war world system. It further introduced the Hellenic heritage into the world of free markets as a vehicle for economic development, political stabilization and modernization. Ultimately, purified in the springs of antiquity, both victorious America and civil-war-wrecked Greece re-affirmed their democratic legacies and pledged to combat communism with Doric columns and tourism.

PRIMARY SOURCES CONSULTED

Alison Frantz Papers (C0772), Manuscripts Division, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

Carl W. Blegen Papers, Archives, American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

ASCSA AdmRec: Administrative Records, Archives, American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

REFERENCES

Bailyn, B. 1992. The Ideological Origins of American Revolution, Cambridge, MA.

Hughes, R. T. 2004. Myths America Lives By, Urbana.

Panourgia, N. 2004. “Colonizing the Ideal. Neo-classical Articulations and European Modernity,” Agelaki 9, pp. 165-176.

Thanks for your post, Despina.

It was good to think again about the issues you raised. In regard to your “what if”, it might be interesting to examine more generally which communist countries broke with their nationalist myths of continuity and exceptionalism, and which did not. In the case of Greece I wonder if the Left, had it been victorious in the Civil War, would have broken with the predominant nationalist narratives. Certainly Albania, with an equally strong national myth based on Illyrianism did not reject it; it was too useful. For a good discussion see Miraj and Zeqo, Antiquity 1993, pp. 123-125: also Galaty and Watkinson eds., The Archaeology Under Dictatorship, pp. 8:

“Instead of rejecting [Albania’s] history. Hoxha embraced it …”.

Another thought: I doubt Blegen was ever considering the marketing antiquities, but rather had in mind cultural exchanges of the sort that he and Kourouniotis had brokered between museums and universities in the later 1920s. For example, native American antiquities were sent to the National Museum in exchange for Greek antiquities at that time, and there was briefly a program in place to allow sherd collections to be formed in American universities.

[…] Communism, Hellenism, and Blegen. […]

[…] was rented to the State Department. (An earlier post to this blog by Despina Lalaki, titled “On Communism and Hellenism: An Archaeologist’s Perspective,” examined the role that Carl Blegen played in promoting U.S. policy in the years following […]