A Journey in the Mediterranean on the Eve of the Great War, 1914.

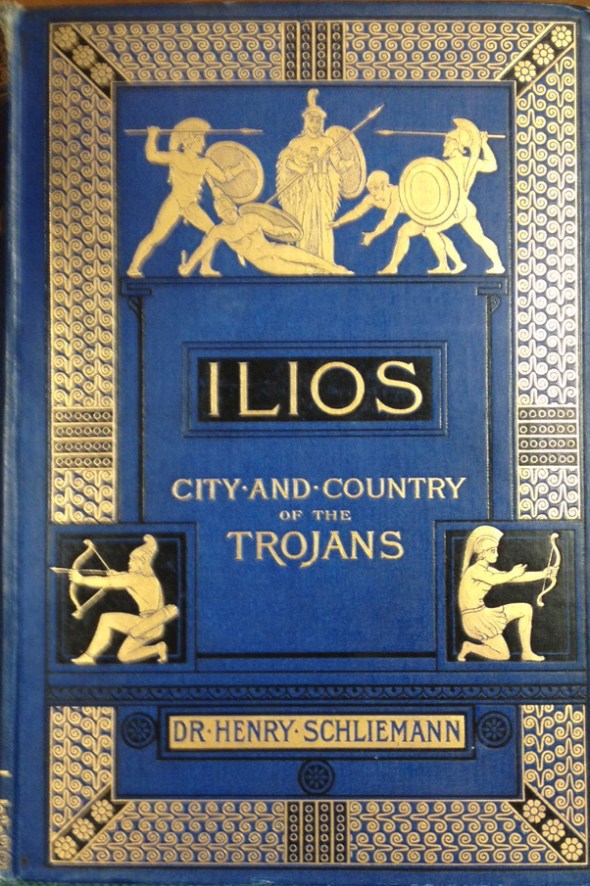

Posted: November 20, 2022 Filed under: Archival Research, Biography, History of Archaeology, Mediterranean Studies, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism, Uncategorized | Tags: Alice Calvert Bacon, Dardanelles, Delphi, Francis H. Bacon, Great War, Guy B. Pears, Julia Dragoumis, Olympia, Poros Island 6 CommentsOn July 4th, 1914, Francis Henry Bacon (1856-1940) and his wife Alice (née Calvert) departed from New York aboard the S.S. Kaiser Frantz Joseph (the ship would be renamed the President Wilson shortly thereafter). The Dardanelles were their destination, where the Calvert family owned an estate, as well as a farm in nearby Thymbra. This is where Bacon had first met Alice in 1883, when the members of the Assos Excavations received an invitation to dine with Alice’s uncle, Frank Calvert (1828-1908). An amateur archaeologist, Calvert had conducted several excavations in the Dardanelles. Perhaps more importantly, he suggested that Heinrich Schliemann (1822-1890) look for Troy at the site of Hissarlik, not far from Thymbra, in the late 1860s. The Calverts were English expatriates long established in the Dardanelles, who made a living trading commodities with the benefit of consular posts.

The time was not good, however, to travel to Europe and especially to the Balkans and Turkey. Just a few days before, on June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife had been assassinated in Sarajevo. His death sparked a series of events that led Austria with the support of Germany to declare war on Serbia a month later. Within a week, the great powers of Europe were forced to ally with or against the main belligerents. Greece tried to remain neutral until 1917 (in no small part because the Greek King was married to the Kaiser’s sister and thus sympathetic to the German side), but the Ottoman Empire openly supported the Germans.

Retracing his Steps

Bacon, a graduate of M.I.T (1876), first traveled to Greece in 1878, before the American School of Classical Studies was even founded. In 1881 he would join, as chief architect, the Archaeological Institute of America’s excavations at Assos in Western Turkey. Following Assos, Bacon pursued a successful career in interior design on the East Coast of America about which I have written before (Francis H. Bacon: Bearer of Precious Gifts from the Dardanelles). He is also credited with the design of the Shrine of the Declaration of Independence in the Library of Congress. Because of Alice’s attachment to the Calvert house in the Dardanelles, the Bacons frequently crossed the Atlantic. Occasionally, Francis would make a stop in Greece to retrace his steps.

After several stops including the Azores, Algiers, and Naples, the Bacons finally reached Patras on July 16th, where the couple parted. Alice continued on another steamer to the Dardanelles, while Francis planned to spend a week in Greece, starting from Olympia. “Splendid Victory of Paionios, and then the lovely, beautifully finished Hermes of Praxiteles – about the only authentic ancient masterpiece in the world,” Bacon scribbled in his notebook. The authenticity of the statue –whether it was a 4th century B.C. original or a fine Roman copy- had not yet been challenged.

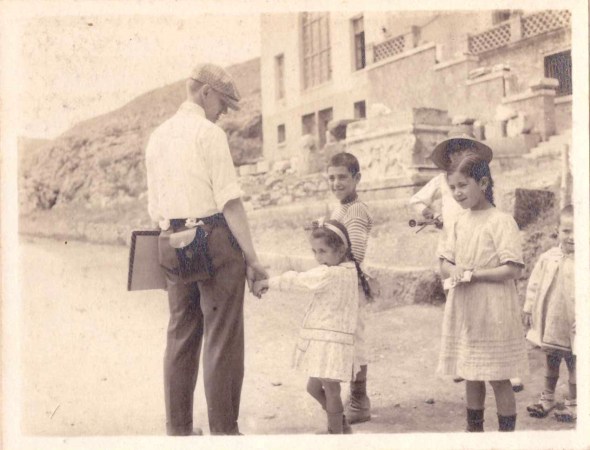

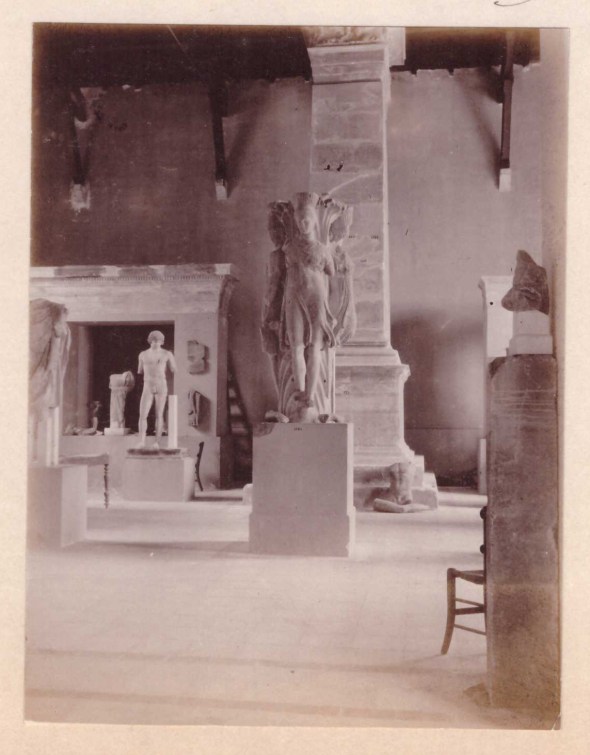

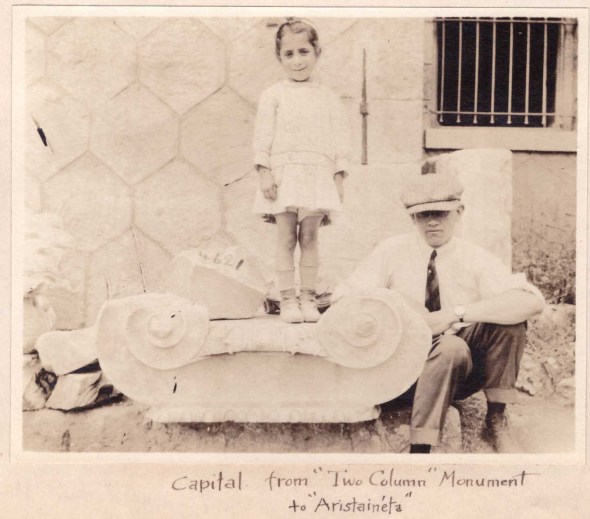

From Patras, Bacon took a little steamer to Itea. At Delphi he was much impressed by the restoration of the Athenian Treasury, which the French had completed a few years earlier (1903-1906.) He only wished that “they had restored the acroteria, two horses with naked riders prancing off the corners of the pediment.” Bacon, an ardent photographer, did not miss a chance to capture monuments and landscape, as well as to experiment with interior photography, which was exceptionally difficult at the time. “Back to the Museum where the Ephor Contoleon is very obliging and invited us to photo and measure anything we like.” I cherish Bacon’s interior photos because we catch glimpses of the old museum displays. To him we owe a partial view of the old Delphi Museum, built in 1903, and several charming photos of the local children who had befriended one of his fellow travelers. See slideshow below.

After two days at Delphi, Bacon headed off for Athens. “Start at Itea at 5 A.M. Steamer at 6:30 for Corinth Canal and Piraeus. There has been a landslide in the canal and the little steamer almost climbs over a pile of clay and earth in the narrow channel. Reach Piraeus at 4 P.M. Drive to Athens over the dusty road. Go to Hotel Minerva where I spent winter in 1883, now rather dirty and forlorn.”

(The Hotel Minerva located at Stadiou 5 operated until 1991. When Bacon first stayed in it in 1883, it was known as Αι Αθήναι. For more information and a photo of the hotel, check out the site of the Greek Literary and Historical Archive.)

Read the rest of this entry »“Who Doesn’t Belong Anywhere, Has a Chance Everywhere”: The Formative Years of Emilie Haspels in Greece.

Posted: November 1, 2020 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, History of Archaeology, Philhellenism, Women's Studies | Tags: Emilie Haspels, Francis H. Bacon, John Beazley, Wilhelm Dörpfeld, Winifred Lamb 3 CommentsBY FILIZ SONGU

Filiz Songu studied archaeology in Izmir and Ankara. As an independent scholar, she works for the Allard Pierson in Amsterdam and is a staff member of the Plakari Archaeological Project in Southern Euboia. She just completed her biographical research into the life and work of Dutch archaeologist Emilie Haspels. In her contribution to From the Archivist’s Notebook, she discusses Haspels’s early formative years in pre-WW II Greece, and the challenges she and other women archaeologists of her time met in a male-dominated field. Since Haspels worked with many foreign archaeological schools in Greece, Songu’s essay is literally a “Who’s Who” of foreign archaeology in interwar Greece.

Caroline Henriëtte Emilie Haspels (1894–1980) was a prominent classical archaeologist in the Netherlands in the decades after WW II. She was the first female professor of Archaeology at the University of Amsterdam and the first female director of the Allard Pierson Museum. Most scholars know her from her study The Highlands of Phrygia. Sites and Monuments (1971), which is still a reference work on the rock-cut monuments in the Phrygian Highlands in central Turkey. For another group of academicians, Emilie Haspels is known for her other classic publication, Attic Black-Figured Lekythoi (1936).

One may wonder what the connection is between these two widely differing fields of specialization. When I started my biographical research into the life and work of Emilie Haspels, my original focus was on her pioneering fieldwork in Turkey. However, when I dug deeper into her personal documents, I discovered more about other significant periods of her life. Her archive provided glimpses of, for instance, her time in Shanghai in 1925–26, and her enforced stay in Istanbul during WW II. It shows how the twists and turns of history affected both her private and her academic life. Key to understanding her archaeological carrier is what I like to call her “Greek period.” The years she spent in Greece in the 1930s doing her PhD research appear to be her formative years as an archaeologist. With the field experience and special skills she acquired in Greece, she paved the way, perhaps unconsciously, to the Phrygian Highlands, which became her life’s work. It was also during her Greek period that she started to build up a wide international network. Haspels’s personal documents and correspondence in various Dutch archives provide complementary information about the scholarly community in pre-WW II Athens and connect with the writings in Natalia Vogeikoff-Brogan’s blog.

Becoming an Archaeologist

Haspels’s Greek period started in the spring of 1929 with her arrival in Athens as a foreign member of the French School. A little about her academic background may be useful here. Haspels had studied Classics at the University of Amsterdam between 1912 and 1923. She minored in Ancient History and Classical Archaeology, attending Jan Six’s classes.

Francis H. Bacon: Bearer of Precious Gifts from the Dardanelles

Posted: June 9, 2019 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Art History, Biography, History of Archaeology, Mediterranean Studies, Philhellenism | Tags: Assos Escavations, Francis H. Bacon, Frank Calvert, Stargazer 13 CommentsI first came to know Bacon’s name when, as a student of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or the School hereafter) in 1989-1990, I was asked to report on the Assos Excavations during the School’s trip to Asia Minor. Assos, an affluent, ancient Greek city in the Çanakkale Province and a colony of Lesbos, is known for having erected the only Doric temple in Asia Minor, where the dominant style was Ionic. Francis Henry Bacon (1856-1940) was the architect of the excavations, which were funded by the Archaeological Institute of America (AIA) and took place from 1881 to 1883, as well as one of the three co-authors (with Clarke and Koldewey) of a final publication that was not completed until 1921. Although Bacon’s name appears second, the publication would not have appeared without his dedication and persistence. Joseph T. Clarke (1856-1920) had given up on it long before, and Robert J. Koldewey (1855-1925) had dedicated most of his life to uncovering Babylon.

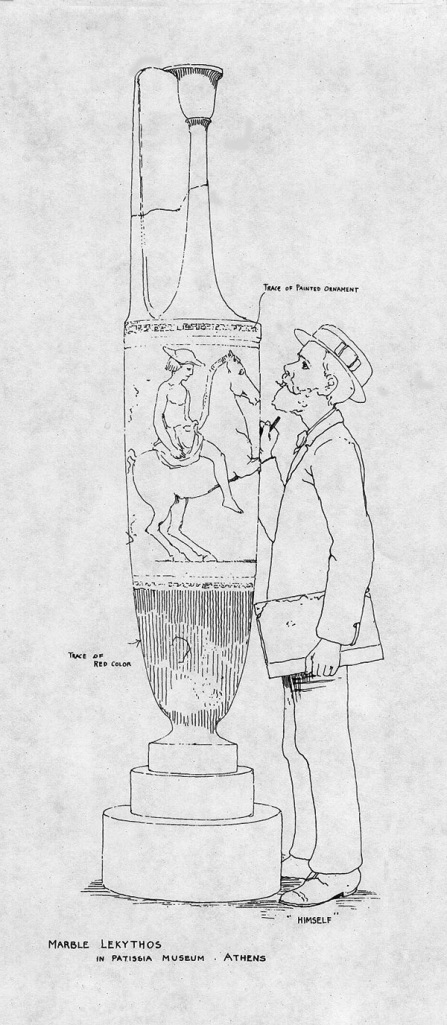

In 1878, Francis H. Bacon and Joseph T. Clarke bought a sailboat, the “Dorian,” in London and sailed to Athens by way of Holland, the Rhine, the Danube, the Black Sea, and the Aegean. Here a self-sketch by Bacon while examining a marble lekythos at the National Archaeological Museum. Source: MIT Libraries, Institute Archives and Special Collections.

“All Americans Must Be Trojans at Heart”: A Volunteer at Assos in 1881 Meets Heinrich Schliemann

Posted: August 1, 2015 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, History of Archaeology, Mediterranean Studies, Philhellenism | Tags: Assos Excavations, Charles Wesley Bradley, Eliot Norton, Francis H. Bacon, Heinrich Schliemann, Mytilene 6 CommentsCurtis Runnels, Professor of Archaeology at Boston University, here contributes to The Archivist’s Notebook a story about the discovery of a personal diary of a young American who participated in the Assos excavations in 1881 and had the opportunity to meet Heinrich Schliemann. In addition to doing fieldwork and publishing extensively on Palaeolithic archaeology in Greece, Runnels is also the author of The Archaeology of Heinrich Schliemann: An Annotated Bibliographic Handlist (Archaeological Institute of America; available also as an ebook from Virgo Books). See also his most recent post about Schliemann, titled “Schliemann Turns Over a New Leaf.”

“He was an American citizen himself—and believed that all Americans must be Trojans at heart.” The line above describes Heinrich Schliemann and comes from the personal diary of a young American who met Schliemann at Assos in 1881. Boston native Charles Wesley Bradley (1857-1884) graduated from Harvard in 1880, having studied classics and philosophy with Charles Eliot Norton, the founder of the Archaeological Institute of America and the driving force behind the first American excavations in classical lands at the site of Assos in northwestern Turkey. Read the rest of this entry »