“You Undoubtedly Remember Mr. L. E. Feldmahn”: The Bulgarian Dolls of the Near East Foundation

Posted: August 31, 2024 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Economic History, Greek Folk Art, Greek Folklore, History, History of Archaeology, Mediterranean Studies, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism, Uncategorized | Tags: Dolls, Leonty E. Feldmahn, Near East Foundation, Near East Industries, Near East Industries Sofia, Near East Relief Museum, Priscilla Capps Hill, Rockefeller Archives Center 2 CommentsJack L. Davis, Carl W. Blegen Professor of Greek Archaeology at the University of Cincinnati and a former director of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (2007-2012), here contributes an essay about Leonty E. Feldmahn, the man who conceived and produced in the 1930s the Bulgarian dolls of the Near East Foundation.

One rewarding sidelight of researching institutional history is that, from time to time, it affords an opportunity to resurrect once well-known individuals who have been lost to history. Here I call attention to a fascinating man, who, throughout much of his life, made outsize contributions to addressing one Balkan refugee crisis that resulted from the Russian Revolution of 1917. In the years prior to World War II, his activities in Bulgaria were sometimes tangential to those of certain individuals known to readers of this blog through the intermediary of the Near East Industries subsidiary of the Near East Foundation.

I only learned of Leonty E. Feldmahn recently and by accident. I didn’t remember him from any earlier reading. Feldmahn is not mentioned in the standard history of the Near East Foundation, or on the Foundation’s historical web site. He appears only three times in the New York Times: when he was awarded the Bulgarian Cross for Philanthropy from King Boris (he had in 1923 established “a playground and children’s club in Sofia serving 4200 poor children,” December 31, 1935, p. 17); earlier in 1935, when the character of the playground and club was described in detail (April 21, 1935, pp. 78, 80); and in his obituary (January 6, 1962, p. 16).

Do I Really Want to Be an Archaeologist?

Posted: July 7, 2024 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Book Reviews, History of Archaeology, Mediterranean Studies, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism, Uncategorized, Women's Studies | Tags: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Archaeology, Athens, College Year in Athens, Eugene Vanderpool, Franchthi Cave, greece, History, Karen D. Vitelli, Porto Cheli Project, travel 13 CommentsThe first time I heard her name was in 1986 at Tsoungiza, Nemea. I had just been awarded a Fulbright fellowship to go to Bryn Mawr College for graduate school. James (Jim) C. Wright, one of the cο-directors of the Nemea Valley Project and a Fulbright fellow himself extended an invitation to me, Alexandra (Ada) Kalogirou and Maria Georgopoulou, the other two Greek Fulbrighters, to join the excavation, as a way of becoming familiar with the American way of life and education system. Ada was going to go to Indiana University to study Greek prehistory with Thomas W. Jacobsen (1935-2017) and Karen D. Vitelli (1944-2023).

I must have heard about Vitelli on and off over the next 10-15 years, but I never met her in person. I didn’t even know what she looked like. Then, in 2010, as I was preparing an exhibition to celebrate the 130th anniversary of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (the School, hereafter), I sent an email to various people asking for photos from the time they were students at the School. Stephen (Steve) G. Miller, former director of the School and a student at the School in the late 1960’s, sent me a few. One of the photos showed a tall, slim, dark-haired woman, who made an indelible impression on me. Several years later (2013), Kaddee (as she was known to nearly everyone) appeared at Mochlos together with her friend, archaeologist Catherine Perlès, at a wedding party for Tristan (Stringy) Carter, as guests of Tom Strasser, her former student. (By then Vitelli was Professor Emerita of Archaeology and Anthropology from Indiana University, Bloomington.) That was the first and last time I saw her in person.

Becoming: Bert Hodge Hill, 1906-1910 (Part I)

Posted: January 1, 2024 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Crete, History of Archaeology, Mediterranean Studies, Modern Greek History, Uncategorized | Tags: Archaeology, Athens, Bert Hodge Hill, europe, George W. Elderkin, greece, James R. Wheeler, Kendall K. Smith, Mochlos, Richard Berry Seager, Theodore W. Heermance, travel 10 CommentsThe re-discovery of a small cache of old photos depicting students at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or School hereafter) from 1907-08 inspired me to write about the first years of Bert Hodge Hill’s directorship at the School. [1]

The photos depict four men and one woman: George Wicker Elderkin (1879-1965), Kendall Kerfoot Smith (1882-1929), Charles Edward Whitmore (1887-1970), Henry Dunn Wood (1882-1940), and Elizabeth Manning Gardiner (1879-1958). Of the five, Elderkin, Smith, and Wood were second year students at the School. In 1908, Elderkin, who already held a PhD from Johns Hopkins (1906), succeeded Lacey D. Caskey as Secretary of the School, a position he held for two years (1908-10). Smith came to the School in 1906 holding the Charles Eliot Norton Fellowship, established by James Loeb in 1901 for Harvard or Radcliffe students. Wood, a trained architect with a BS in Architecture from the University of Pennsylvania, was the second recipient of the Fellowship in Architecture (1906-08) that was funded by the Carnegie Institution in Washington.

Of the new students, Whitmore, another Harvard man, was the Charles Eliot Norton Fellow for 1907, and Gardiner, the only woman in the photos, was a graduate of Radcliffe College (1901), with an MA from Wellesley (1906), and a recipient of the Alice Palmer Fellowship that supported female students.

Read the rest of this entry »Disjecta Membra: The Personal Papers of Minnie Bunker

Posted: July 8, 2023 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Classics, History of Archaeology, Mediterranean Studies, Women's Studies | Tags: Agnes Baldwin, Chaironea Lion, Charles Weller, Constitution Square, Πλατεία Συντάγματος, Minnie Bunker, Nancy Perrin Weston 9 CommentsWe have been processing a large shipment of files that the Princeton office of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or School hereafter) mailed to Greece during their relocation in 2021. The files contain many surprises, especially those associated with the production of the School’s Newsletter. There we found a trove of unpublished (and unknown) photos and among other material an envelope with letters, calling cards, and photos that once belonged to Minnie Bunker (1867-1959).

Minnie was a high school teacher and a student at the School in 1900-1901 who returned in 1906-1907 and again in 1911-1912. She also is no stranger to the School’s Archives which already contained a small collection of her water-damaged photographs and letters, as well as an 1894 Baedeker, which her grandniece Nancy Perrin Weston (1922-2011) mailed to Athens in the 2000’s. After her aunt’s death in 1959, Nancy also spent time in Greece, working for renowned architect Constantine Doxiadis and volunteering in the School’s Library from 1963-1964. Minnie must have transmitted her love for Greece and the School to her grandniece because in 2011, the year of Nancy’s death, the School received $25,000 from her estate.

The thrill of archival research is not limited to discovery but encompasses rediscovery. The envelope that we found in 2020 contained another small cache of Minnie Bunker papers that Weston had shipped to the School’s office in New York in 1981, when the School was actively looking for letters and photos of past students and members on the occasion of its upcoming centenary.

A Journey in the Mediterranean on the Eve of the Great War, 1914.

Posted: November 20, 2022 Filed under: Archival Research, Biography, History of Archaeology, Mediterranean Studies, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism, Uncategorized | Tags: Alice Calvert Bacon, Dardanelles, Delphi, Francis H. Bacon, Great War, Guy B. Pears, Julia Dragoumis, Olympia, Poros Island 6 CommentsOn July 4th, 1914, Francis Henry Bacon (1856-1940) and his wife Alice (née Calvert) departed from New York aboard the S.S. Kaiser Frantz Joseph (the ship would be renamed the President Wilson shortly thereafter). The Dardanelles were their destination, where the Calvert family owned an estate, as well as a farm in nearby Thymbra. This is where Bacon had first met Alice in 1883, when the members of the Assos Excavations received an invitation to dine with Alice’s uncle, Frank Calvert (1828-1908). An amateur archaeologist, Calvert had conducted several excavations in the Dardanelles. Perhaps more importantly, he suggested that Heinrich Schliemann (1822-1890) look for Troy at the site of Hissarlik, not far from Thymbra, in the late 1860s. The Calverts were English expatriates long established in the Dardanelles, who made a living trading commodities with the benefit of consular posts.

The time was not good, however, to travel to Europe and especially to the Balkans and Turkey. Just a few days before, on June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife had been assassinated in Sarajevo. His death sparked a series of events that led Austria with the support of Germany to declare war on Serbia a month later. Within a week, the great powers of Europe were forced to ally with or against the main belligerents. Greece tried to remain neutral until 1917 (in no small part because the Greek King was married to the Kaiser’s sister and thus sympathetic to the German side), but the Ottoman Empire openly supported the Germans.

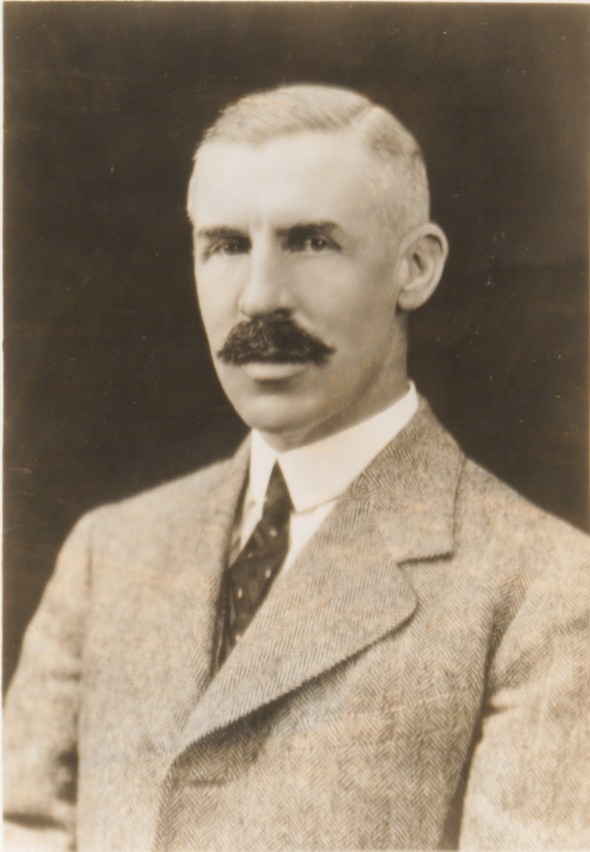

Retracing his Steps

Bacon, a graduate of M.I.T (1876), first traveled to Greece in 1878, before the American School of Classical Studies was even founded. In 1881 he would join, as chief architect, the Archaeological Institute of America’s excavations at Assos in Western Turkey. Following Assos, Bacon pursued a successful career in interior design on the East Coast of America about which I have written before (Francis H. Bacon: Bearer of Precious Gifts from the Dardanelles). He is also credited with the design of the Shrine of the Declaration of Independence in the Library of Congress. Because of Alice’s attachment to the Calvert house in the Dardanelles, the Bacons frequently crossed the Atlantic. Occasionally, Francis would make a stop in Greece to retrace his steps.

After several stops including the Azores, Algiers, and Naples, the Bacons finally reached Patras on July 16th, where the couple parted. Alice continued on another steamer to the Dardanelles, while Francis planned to spend a week in Greece, starting from Olympia. “Splendid Victory of Paionios, and then the lovely, beautifully finished Hermes of Praxiteles – about the only authentic ancient masterpiece in the world,” Bacon scribbled in his notebook. The authenticity of the statue –whether it was a 4th century B.C. original or a fine Roman copy- had not yet been challenged.

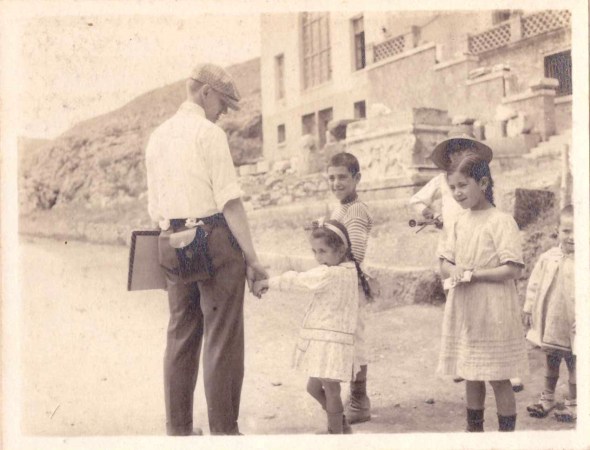

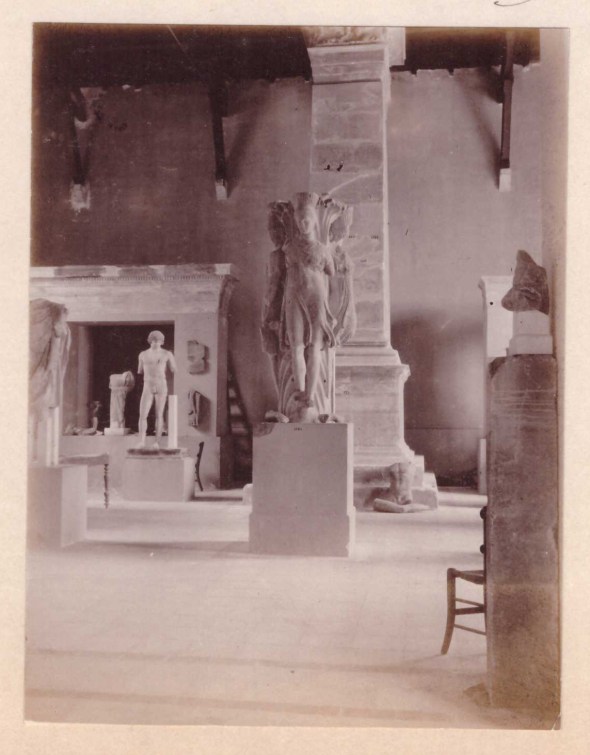

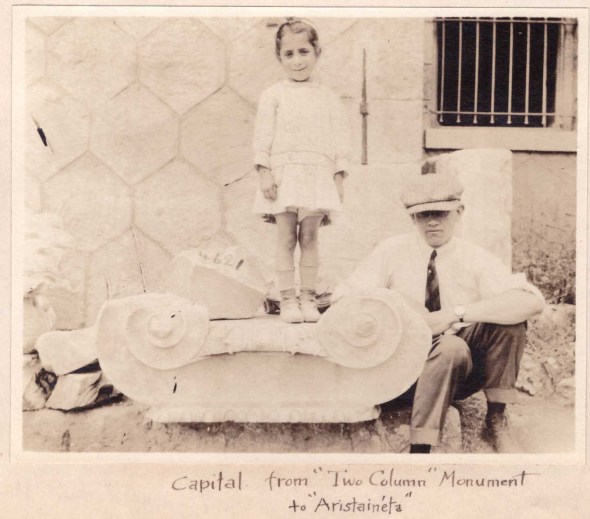

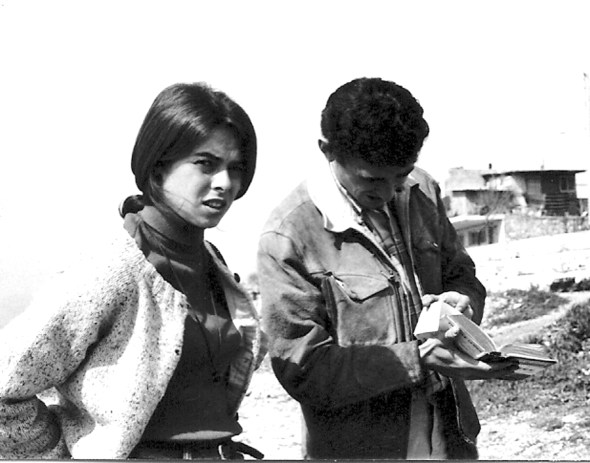

From Patras, Bacon took a little steamer to Itea. At Delphi he was much impressed by the restoration of the Athenian Treasury, which the French had completed a few years earlier (1903-1906.) He only wished that “they had restored the acroteria, two horses with naked riders prancing off the corners of the pediment.” Bacon, an ardent photographer, did not miss a chance to capture monuments and landscape, as well as to experiment with interior photography, which was exceptionally difficult at the time. “Back to the Museum where the Ephor Contoleon is very obliging and invited us to photo and measure anything we like.” I cherish Bacon’s interior photos because we catch glimpses of the old museum displays. To him we owe a partial view of the old Delphi Museum, built in 1903, and several charming photos of the local children who had befriended one of his fellow travelers. See slideshow below.

After two days at Delphi, Bacon headed off for Athens. “Start at Itea at 5 A.M. Steamer at 6:30 for Corinth Canal and Piraeus. There has been a landslide in the canal and the little steamer almost climbs over a pile of clay and earth in the narrow channel. Reach Piraeus at 4 P.M. Drive to Athens over the dusty road. Go to Hotel Minerva where I spent winter in 1883, now rather dirty and forlorn.”

(The Hotel Minerva located at Stadiou 5 operated until 1991. When Bacon first stayed in it in 1883, it was known as Αι Αθήναι. For more information and a photo of the hotel, check out the site of the Greek Literary and Historical Archive.)

Read the rest of this entry »