A Journey in the Mediterranean on the Eve of the Great War, 1914.

Posted: November 20, 2022 Filed under: Archival Research, Biography, History of Archaeology, Mediterranean Studies, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism, Uncategorized | Tags: Alice Calvert Bacon, Dardanelles, Delphi, Francis H. Bacon, Great War, Guy B. Pears, Julia Dragoumis, Olympia, Poros Island 6 CommentsOn July 4th, 1914, Francis Henry Bacon (1856-1940) and his wife Alice (née Calvert) departed from New York aboard the S.S. Kaiser Frantz Joseph (the ship would be renamed the President Wilson shortly thereafter). The Dardanelles were their destination, where the Calvert family owned an estate, as well as a farm in nearby Thymbra. This is where Bacon had first met Alice in 1883, when the members of the Assos Excavations received an invitation to dine with Alice’s uncle, Frank Calvert (1828-1908). An amateur archaeologist, Calvert had conducted several excavations in the Dardanelles. Perhaps more importantly, he suggested that Heinrich Schliemann (1822-1890) look for Troy at the site of Hissarlik, not far from Thymbra, in the late 1860s. The Calverts were English expatriates long established in the Dardanelles, who made a living trading commodities with the benefit of consular posts.

The time was not good, however, to travel to Europe and especially to the Balkans and Turkey. Just a few days before, on June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife had been assassinated in Sarajevo. His death sparked a series of events that led Austria with the support of Germany to declare war on Serbia a month later. Within a week, the great powers of Europe were forced to ally with or against the main belligerents. Greece tried to remain neutral until 1917 (in no small part because the Greek King was married to the Kaiser’s sister and thus sympathetic to the German side), but the Ottoman Empire openly supported the Germans.

Retracing his Steps

Bacon, a graduate of M.I.T (1876), first traveled to Greece in 1878, before the American School of Classical Studies was even founded. In 1881 he would join, as chief architect, the Archaeological Institute of America’s excavations at Assos in Western Turkey. Following Assos, Bacon pursued a successful career in interior design on the East Coast of America about which I have written before (Francis H. Bacon: Bearer of Precious Gifts from the Dardanelles). He is also credited with the design of the Shrine of the Declaration of Independence in the Library of Congress. Because of Alice’s attachment to the Calvert house in the Dardanelles, the Bacons frequently crossed the Atlantic. Occasionally, Francis would make a stop in Greece to retrace his steps.

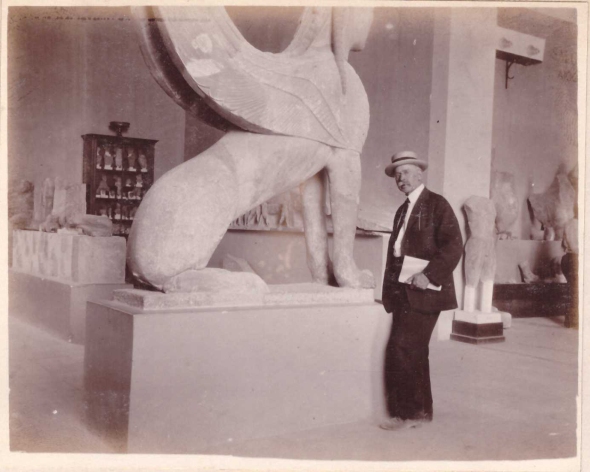

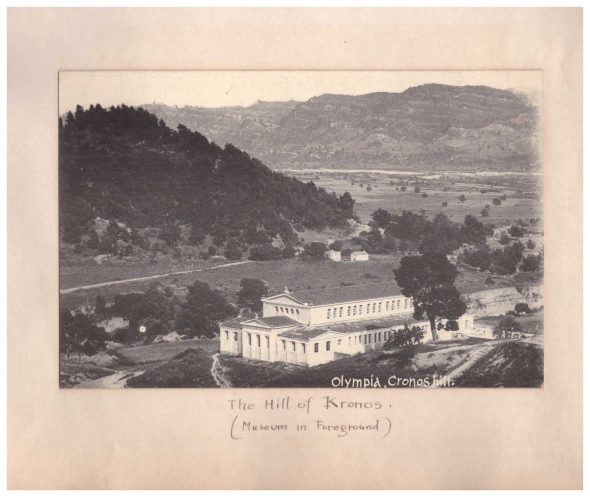

After several stops including the Azores, Algiers, and Naples, the Bacons finally reached Patras on July 16th, where the couple parted. Alice continued on another steamer to the Dardanelles, while Francis planned to spend a week in Greece, starting from Olympia. “Splendid Victory of Paionios, and then the lovely, beautifully finished Hermes of Praxiteles – about the only authentic ancient masterpiece in the world,” Bacon scribbled in his notebook. The authenticity of the statue –whether it was a 4th century B.C. original or a fine Roman copy- had not yet been challenged.

From Patras, Bacon took a little steamer to Itea. At Delphi he was much impressed by the restoration of the Athenian Treasury, which the French had completed a few years earlier (1903-1906.) He only wished that “they had restored the acroteria, two horses with naked riders prancing off the corners of the pediment.” Bacon, an ardent photographer, did not miss a chance to capture monuments and landscape, as well as to experiment with interior photography, which was exceptionally difficult at the time. “Back to the Museum where the Ephor Contoleon is very obliging and invited us to photo and measure anything we like.” I cherish Bacon’s interior photos because we catch glimpses of the old museum displays. To him we owe a partial view of the old Delphi Museum, built in 1903, and several charming photos of the local children who had befriended one of his fellow travelers. See slideshow below.

After two days at Delphi, Bacon headed off for Athens. “Start at Itea at 5 A.M. Steamer at 6:30 for Corinth Canal and Piraeus. There has been a landslide in the canal and the little steamer almost climbs over a pile of clay and earth in the narrow channel. Reach Piraeus at 4 P.M. Drive to Athens over the dusty road. Go to Hotel Minerva where I spent winter in 1883, now rather dirty and forlorn.”

(The Hotel Minerva located at Stadiou 5 operated until 1991. When Bacon first stayed in it in 1883, it was known as Αι Αθήναι. For more information and a photo of the hotel, check out the site of the Greek Literary and Historical Archive.)

Read the rest of this entry »The Forgotten Olympic Exhibition: Georg Alexander Mathéy’s Contribution to the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin.

Posted: August 2, 2022 Filed under: Archival Research, Art History, Biography, Exhibits, History of Archaeology, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism | Tags: Georg Alexander Mathéy, Polyxene Roussopoulos Mathéy, Walter Hege 3 CommentsBY ALEXANDRA KANKELEIT

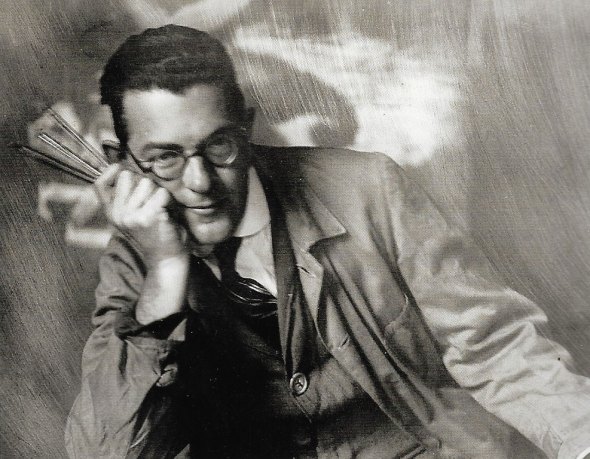

Alexandra Kankeleit is a German-Greek archaeologist and historian. She has been researching German archaeology in Greece during the Nazi period for several years. Since July 2021 she has been working for the CeMoG (Centrum Modernes Griechenland) at the Freie Universität Berlin, where she will teach a seminar on the 1936 Summer Olympics in the upcoming winter semester. Here she contributes an essay about the German artist Georg Alexander Mathéy (1884-1968), who lived in Greece in the 1930s and whose work was displayed in the Summer Olympics of 1936.

The Badische Landesbibliothek in Karlsruhe (BLB) has held a large part of the estate of painter and writer Georg Alexander Mathéy (1884-1968) since 1993. In 2017, the BLB organized an exhibition, titled Sprachbilder – Bildersprache: Die Künstler Helene Marcarover und Georg Alexander Mathéy, to showcase the works of Mathéy together with those of another artist, the painter and poet Helene Markarova (1904-1992). Both artists, whose work was shaped by the two wars, by migration and alienation, were able through literature to transform images into words, and vice versa. A wonderful accompanying publication provides insights into Mathéy’s life and creative work (Axtmann – Stello 2017).

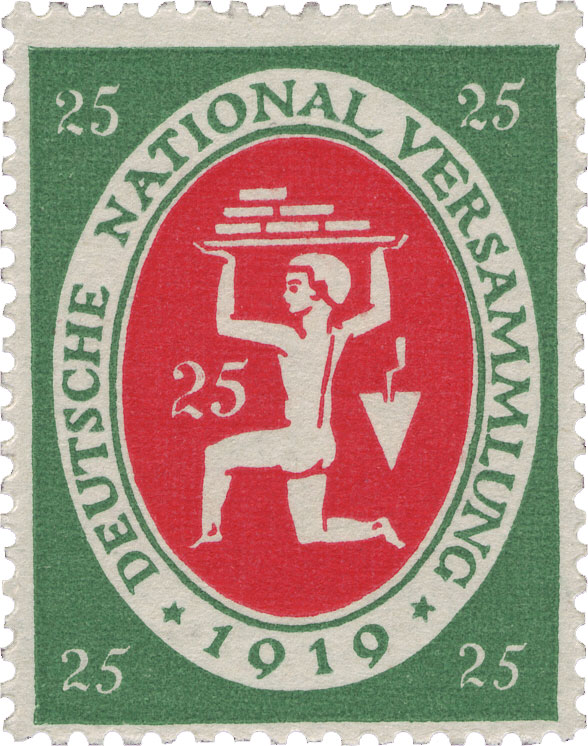

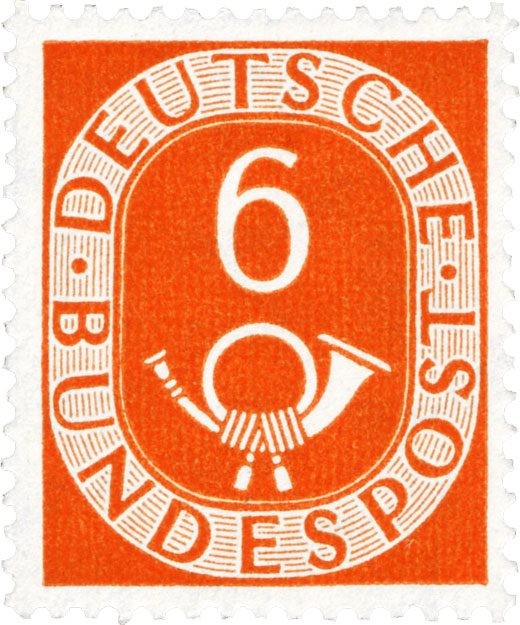

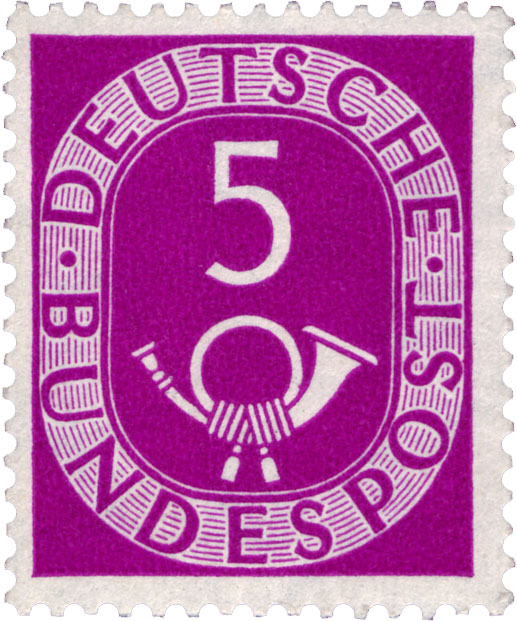

Trained as an architect in Budapest, Mathéy made his name as an illustrator of numerous books and magazines, achieving commercial success already at a young age. He also designed stamps, textiles, and a Rosenthal coffee service. Two of his stamp designs are still remembered today because of their intense colors and memorable motifs: the “bricklayer” (1919) and the “post horn” (1951). They can be described as classics of German stamp design.

In addition to this modern, highly reductivist formal language, Mathéy also mastered other, more traditional media, primarily in his large-scale watercolors and oil paintings.

I became interested in Mathéy’s largely forgotten contribution to the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin. The starting point is material from the archives of the BLB, which provided new and important information about Mathéy. (I would like to thank the director of the BLB, Julia Hiller von Gaertringen, for her interest and active support in my project. A detailed German version of this article can be found on the BLBlog.) Further information can also be found in an unpublished research paper on Georg Alexander Mathéy, which the designer Ulrike Jänichen completed in 2003 under the direction of Professor Mechthild Lobisch at the Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule in Halle. She kindly made her work available to me.

Mrs. Jarley’s Waxworks and a Jolly Jumble of Jests, Christmas 1903

Posted: June 19, 2022 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Classics, History of Archaeology | Tags: Edith Hall, Fritz Darrow, Gorham Stevens, Harold Fowler, Katherine Welsh, Lacey Caskey, Theodore W. Heermance, Theosophy 4 CommentsThe story of Mrs. Jarley’s Waxworks forms part of Charles Dickens’s novel The Old Curiosity Shop, published in 1841. Although Mrs. Jarley is a minor character in the plot, her story gained much popularity in British and American amateur theater and was performed widely at private parties in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Inspired by Madame Tussaud’s famous wax models, Dickens’s Mrs. Jarley was the proprietor of a collection of still wax figures which she displayed on a stage protected by a cord.

In 1873, George Bradford Bartlett (1832-1896), an American from Massachusetts, published Mrs. Jarley’s Far-Famed Collection of Waxworks. Enriched with more characters, real and fictitious, Bartlett’s book is essentially a guidebook for staging amateur performances with animated pantomimes, also known as tableaux vivants. Unlike Dickens, Bartlett’s waxworks were fitted with clockworks inside so that they could move and “go through the same motions they did when living.” Louisa May Alcott (1832-1888), the author of Little Women, frequently participated in tableaux vivants, with Bartlett as her stage manager (Chapman 1992).

These kinds of performances were often used as a vehicle for local fund-raising. Socialites such as Mrs. Astor and Mrs. Vanderbilt often hosted tableaux vivants with young, unmarried women of high society performing in various roles (Chapman 1992).

One such performance took place at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or the School hereafter), on Christmas in 1903. It is one of these rare instances, where an event described blow-by-blow in a private letter, has also its visual match. In the School’s large Archaeological Photographic Collection (APC), in addition to photos documenting excavation and other fieldwork, there is a small number of images capturing more private aspects of life at 54 Speusippou (now Souidias).

According to the author of the letter, Theodore Woolsey Heermance (1872-1905), the idea of a party inspired by Mrs. Jarley’s Waxworks belonged to Mrs. Fowler, “who had seen and participated in several such.” Heermance was the new director of the School, having started his term in the fall of 1903. Just a year over thirty, he had studied at Yale and was the grandson of Theodore Dwight Woolsey, President of Yale University from 1846 to 1871. Helen Bell Fowler (1848-1909) was the wife of Harold Fowler, the School’s Professor of Greek Language and Literature for the academic year 1903-1904.

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

If the original idea of a tableau vivant belonged to Mrs. Fowler, it was Edith Hall “who took the matter up with her usual energy and consented to be Mrs. Jarley. Between them and Miss Welch [Welsh] – a member of the British School, who lives at the same pension as Miss Hall- they planned for the different parts,” wrote Heermance to his mother and sister on December 27, 1903. He further described the costumes “as more or less burlesque, otherwise with a limited outfit they would have fallen rather flat.”

Edith Hayward Hall (1877-1943) was the Agnes Hoppin Memorial Fellow and the only female student at the School that year. Having earned a B.A. from Smith College, Hall had enrolled at Bryn Mawr College for graduate school. That Christmas “Miss Hall as Mrs. Jarley was capital and with a big hat on kept up a continuous stream of description of her automations and of banter with the audience” wrote Heermance and went on to describe the wax figures “in the order they were uncovered and set agoing.”

“Darrow was Xerxes in a golden crown and neck ornaments and red robes. His business was to rise from his throne three times as Xerxes is said by Herodotus to have done on one occasion in anger.” Heermance is referring to a passage from Book VII of Herodotus that describes the Battle of Thermopylae: “And during these onsets, it is said that the king, looking on, three times leaped up from his seat, struck with fear for his army” [7. 212].

Front row (l-r): Harold Fowler (Agamemnon), Lacey Caskey (Columbus), William Battle (Baby Heracles), Gorham Stevens (Miss Muffet), Fritz Darrow (Xerxes). Back row (l-r): Edith Hall (Mrs. Jarley), Robert McMahon (Klytaimnistra), Harold Hastings (Lord Byron), May Darrow (Zoe or Maid of Athens), Katherine Welsh (Sappho), and Theodore Heermance (Mrs. Jarley’s Assistant).

The Cretan Enigma

Posted: May 20, 2022 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Classics, History of Archaeology, Philhellenism, Uncategorized | Tags: Charles Henry Hawes, Crete, Harriet Ann Boyd 1 CommentBY CURTIS RUNNELS – PRISCILLA MURRAY

In February 2022, Curtis Runnels, Professor of Archaeology at Boston University, and his wife Priscilla Murray, an anthropologist and Classical archaeologist, contributed to From the Archivist’s Notebook a story (The Cretan Idyll of Harriet Boyd and Charles Henry Hawes) about their purchase of a sketchbook from the early 20th century with watercolors depicting places and people on Crete. At the time, they identified Charles Henry Hawes as the owner of the sketchbook. Soon after their essay was published, they received a communication that cast doubt on the identity of the owner. After doing more research, they felt that they should publish an addendum to their previous essay, in order to let people know that they were probably wrong in their identification, and also open the floor for further discussion concerning the ownership of this precious item.

At a dinner in London in the nineteenth century, the social scientist Herbert Spencer is reported to have said that he had once composed a tragedy, to which the biologist Thomas Henry Huxley quickly replied “I know what it was about: an elegant theory killed by a nasty, ugly little fact.” Our blog “The Cretan Idyll of Harriet Boyd and Charles Henry Hawes” is such a tragedy. From circumstantial evidence we had concluded that a sketchbook in our collection was once owned by Charles Henry Hawes. But now archaeologist Vasso Fotou, who has a copy of Henry’s diary for the spring of 1905, has informed us that the dates in our sketchbook for that time period and the ones in Henry’s diary do not match. That fact proves that the sketchbook was not owned by Henry.

On the dates of the paintings and other sketches of the Aegean islands between Siteia and Athens in the sketchbook, Henry was on Crete. He had been on Crete for a few days when a group of attendees of the First International Congress of Archaeology in Athens, including Harriet Boyd, Sir Arthur Evans, and twelve others arrived in Candia aboard the chartered yacht Astrapi on April 13. Henry visited Harriet at Gournia on April 20, however, and not on April 16 as we had thought, and he remained in Crete after the Astrapi returned to Athens.

The dates in the sketchbook for 1905 suggest a short trip to Crete, and we now believe that it belonged to one of the twelve passengers on the Astrapi. The yacht continued on to the Bay of Mirabello and Siteia, allowing some of the passengers to visit the excavations at Gournia and Palaikastro before the yacht returned to Athens via the islands. Who was in that party of travelers and who could have been the owner? And which of these people is also responsible for the paintings, pencil drawings, and other pictures in New England in 1915 and 1916? It should be noted that the artworks in the sketchbook for both periods are of highly variable quality, and two pencil drawings (one of a sculpture of Heracles in the Mykonos Museum dated to April 20, and one undated portrait of the head of a man who might be Henry) are pasted into the sketchbook and are possibly from a different book. Did more than one person paint or draw in the book?

While the sketchbook was not Henry’s, we nevertheless know that the conference visitors were acquainted with Harriet and probably also with Henry whom they would have met on the side trip to Palaikastro where he was excavating. The acquaintance of the sketchbook owner with the Hawes may have been renewed in New England in 1915/1916 and it is possible that some of the portraits in the book are of Henry, Harriet, and their children after all.

We have considered two “suspects,” perhaps Edith Hall or Gisela Richter, both of whom were in Harriet’s circle and both of whom were on Crete in 1905 and who subsequently lived in the U.S. on the east coast in 1915/1916. Unfortunately, in the absence of any evidence tying either one of them to the sketchbook we can only speculate that one of these women, both close friends with Harriet, could be the sketchbook owner.

Recalling a Museum Theft

Posted: April 21, 2022 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Art History, Classics, History of Archaeology, Mediterranean Studies, Philhellenism | Tags: Athenian Agora Excavations, Charles H. Morgan, Christine Alexander, Eugene Vanderpool, Homer A. Thompson, Γιάννης Μηλιάδης, John L. Caskey, John Meliades 4 Comments“Sadly, the best candidate for him, the beautifully carved [head] 3, facing right, was stolen from the Agora’s dig house in 1955, while the Stoa of Attalos was under construction.” This sentence caught my attention while reading “Classical Sculpture from the Athenian Agora, Part 2: The Friezes of the Temple of Ares (Temple of Athena Pallenis),” published in Hesperia 88 (2019) by Andrew Stewart and seven co-authors (E. Driscoll, S. Estrin, N. J. Gleason, E. Lawrence, R. Levitan, S. Lloyd-Knauf, and K. Turbeville). Further below in the catalog entry for the head, the exact date of the theft is also mentioned: August 22, 1955.

Stewart et al. refer to a fragmentary male head of high craftsmanship that was found in the Athenian Agora near the northeast corner of the Temple of Ares in 1933. Carved around 430-425 B.C. and identified as Hermes, the small head (H.: 0.147m) is one of forty-nine half-size marble fragments which once decorated the friezes of the Temple of Ares in the Agora (originally the Temple of Athena Pallenis at Pallene). A plan of the Agora with the findspots of the sculptures is included in the Hesperia article, and is also available at https://ascsa.net.

Thefts occur in even the best guarded museums and libraries. Every institution has its own story (or stories) to share or hide. And at least some thefts are committed by those who have “hands-on” access to the collections. A recent example was the return of two valuable journals of Charles Darwin, which were stolen two decades ago from the library of Cambridge University. Others remain lost–the paintings stolen from the Isabella Gardner Museum in Boston in 1990, or the Telephus head, an original by Skopas, removed from the Tegea Museum in 1992.

But back to the little head of Hermes that was inventoried as S 305. I was curious to discover more about its theft. A search in the Archives of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or the School hereafter) yielded considerable information about the event and its aftermath.

On September 6, 1955, the School’s Director, John L. Caskey, found himself in the unpleasant position of reporting to the Chair of the Managing Committee, Charles H. Morgan, that “one of the fine small marble heads from the Altar of Ares in the Agora was stolen recently. You will remember that a series of these heads was on a window sill in the inner courtyard. The head was twisted out of its plaster base. The loss was reported to the Ephor, the Symvoulion discussed it (not unsympathetically, according to George Mylonas), the police were notified, and small notices appeared in the papers. Modiano, who is very alert, picked it up immediately and put a bit in the Times of London. I wonder whether the story reached America. There’s nothing more we can do except, as Homer [Thompson] says, hurry up and move to the Stoa” (AdmRec Box 318/5, folder 8). [The photo on the left and its title are reproduced from Stewart et al. 2019.]

There was a delay of about two weeks between the theft (August 22) and Caskey’s report to Morgan because the School’s Director was not informed immediately. Apparently the staff members of the Agora were slow to convey the news either to the School’s Director or to the Ephor of the Acropolis, John Meliades. Eugene Vanderpool, who was in charge of the Agora Excavations when its Director Homer Thompson was in America, wrote to Thompson on August 29 (seven days after the theft). “Meliades came down this morning and I told him all the details. He was sympathetic and helpful. Later in the morning I took him a written account of the affair drawn up by Kyriakides [Aristeides Kyriakides was the School’s lawyer]… [and] I enclosed several pictures” (Homer A. Thompson Papers, box 68, folder 4).

Since the head had never been published, Meliades urged Vanderpool “to publish it as soon as possible so as to make public the claim to it.” The next day Vanderpool supplied journalist Makis Lekkas of Vima (BHMA) and Nea (NEA) with a short text and a photo which gave the appearance that the Hermes’ head had just been found during cleaning operations in the area of the Temple of Ares. Vanderpool further suggested to Thompson that the theft should be included in the School’s Annual Report, “so that it will become known in the scholarly world. Then if an attempt is made to sell it to a museum it can be identified. Meliades tells me that if a foreign museum buys it, the Greek Gov[ernmen]t can reclaim it as stolen property under existing international agreements.” As planned, on August 31, a short piece appeared at NEA, titled “Σημαντικά ευρήματα εις την Αρχαίαν Αγοράν” (Important finds at the Ancient Agora).

Meliades immediately reported the theft to the Archaeological Council. An off-the-record note by Mylonas, who was present at the Council’s meeting, suggested that members were understanding and “that while it was too bad, such things do happen occasionally.” The Minister of Education, who presided over the Council, personally telephoned the police and reported the theft (Homer A. Thompson Papers, box 68, folder 4, Vanderpool to Thompson, Sept. 1, 1955).

The Cat’s Out of the Bag

Just as he was about to mail his letter, Vanderpool rushed to add a last-minute postscript: “It looks as though the cat were out of the bag. Today’s NEA reports the theft, having gotten it from police bulletin. Modiano [the Greek correspondent in London] called up at 12.10 for more details… and it will be in London Times.” On September 2, the London Times published a note together with a photo of the stolen head: “500 B.C. Bust Stolen from Museum.” By then the Director of the School must have also found out about the theft although there is no mention of Caskey in the dispatches that Vanderpool sent to Thompson or in all their dealings with the Archaeological service.

After that initial interest, the press dropped the matter quickly, but not the Archaeological Service. On September 9, Spyridon Marinatos, Director of Antiquities, Christos Karouzos, Director of the National Archaeological Museum, and Ephor John Meliades visited the “scene of the crime” and met with Vanderpool. Three days later Caskey received an official reprimand signed by the Minister of Education, Achilleas Gerokostopoulos. In it, the School was accused of having inexcusably delayed, almost by a week, in informing the Service of the theft. As a result, the police had lost valuable time. The School was also reproached for not storing such a prime piece of sculpture in a safer location; instead it was in an exposed and unsecure location. Finally, by not publishing it for twenty-two years, the School had made repatriation more difficult in case it had already been smuggled outside Greece (Homer A. Thompson Papers, box 111 folder 1, enclosed in a letter from Caskey to Thompson, Sept. 16, 1955).

“The School gets a black eye out of this, which could have been avoided if we had reported the loss to Meliades at once. In the future I’d like to hear from the Agora staff immediately whenever anything happens that may affect our standing or relations with the officials and the local public,” Caskey rebuked Thompson. The rest of Caskey’s letter referred to the animosities between Greece and Turkey “over the Cyprus business,” and the progress that had been made concerning the reconstruction of the Stoa of Attalos: “The fluting of the eight columns is a fine sight.”

Morgan writing to Vanderpool from the other side of the Atlantic was more sympathetic about the theft. “It is a pity it has gone. I remember it well and believed it to be by one of the sculptors of the Parthenon frieze. Unfortunately this is the kind of thing that happens in the best of regulated museums, one of these things that no number of special guards or protective devices can entirely obviate… such as Princeton three years ago with three Rembrandt prints stolen during a commencement exhibition” (AdmRec 318/5 folder 8, September 13, 1955).

There is one last mention of the stolen head in the School’s records. On September 24, 1955, Vanderpool writing again to Thompson referred to some fake news about the missing head: “A clue which led to the Elsa Maxwell cruise proved false. Someone on the cruise had indeed bought a small head but it was not ours. It is a long and rather amusing story. Dick [Richard Hubbard] Howland knows it and would be glad to tell it if he sees you. I may write it someday.” Vanderpool also added that the Agora staff had “closed the courtyard to the general public: too bad, but really much better so” (Homer A. Thompson Papers, box 68, folder 4).

Maxwell (1883-1963) was a famous gossip columnist who was known for entertaining high-society guests at her parties and being friends with celebrities such as the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, Aristotle Onassis and Maria Callas. In late August 1955 Maxwell together with actress Olivia de Havilland organized a 15-day cruise in the Aegean for 113 members of European royalty and other high-society types, aboard the luxury yacht Achilleus, lent by the Greek shipping magnate, Stavros Niarchos. Although Maxwell’s cruise was not connected to the theft, cruise boats or merchant ships were the main vehicles for smuggling antiquities out of Greece before and after WW II, including the famous New York kouros in the Metropolitan Museum.

Eight Months Later and a Riddle

In search of more information about the stolen marble head, I continued to read correspondence between Caskey and Morgan, whose main concern was the progress of work on the Stoa of Attalos and plans for its inauguration in the late summer of 1956. There I came across a letter titled “Confidential” that Morgan sent to Caskey on May 15, 1956 soon after the May Meeting of the School’s Managing Committee (AdmRec 318/5 folder 9). While in New York, Morgan paid a visit to Christine Alexander (1893-1975), Curator of Greek and Roman Art at the Metropolitan Museum. Morgan was on a mission (sent by Caskey) to see Alexander about a delicate matter, the return to Greece of some object. “Not knowing exactly what approach to take I said ‘I am at your service if you need me’.” Morgan was surprised not so much by the position Alexander took but “from the indomitable conviction with which she spoke.” “Her opinion is that the Metropolitan bought the article in good faith, that the Metropolitan’s funds are charitable funds, invested for the benefit of the people of New York, that it would be improper to ask the citizens of New York to pay for the carelessness of a local museum.” For a moment I wondered if they were talking about the Agora marble head.

But then Alexander further pressed her arguments by pointing out “that the figure had not been published in anything that seems to have reached this country [America], that when the figure was stolen, though everyone knows that such material drifts to the New York market, no notification was received by the Metropolitan nor so far she [knew] by any other museum or private collector.” It was obvious that she was talking about something else, a figure, not a head, that had been stolen from a Greek museum.

Morgan tried to counteract her arguments by saying that if he were a Trustee of the Metropolitan faced with such a problem “I would immediately dig into my own pocket and the pockets of my fellow Trustees to reimburse the city for the cost of the figure and restore it to its original position.” He further added that “this was the time for American institutions to make such gestures and [he] would strongly advise that it be done with the greatest possible attendant publicity.

To which Alexander strongly disagreed believing that it would have had the opposite effect. “Well, we made the rascals give up the swag” Morgan quoted her saying. Morgan promised Caskey that he would continue to press the matter: “I will do everything I can to effect what seems to me a solution indicated morally if not legally.”

I found Caskey’s response in Morgan’s files. In a long letter written from Lerna on May 27, 1956, about a host of issues concerning the reconstruction of the Stoa of Attalos, Caskey finally came to the matter of dispute with the Metropolitan Museum.

I consider it of the greatest importance that the piece be returned. I had not supposed for a minute that there could be any doubt about that. It was published in an extensive study with three clear photographs… And if the funds of the people of New York were misspent by accident –for goodness sake that is no reason for being righteous.

AdmRec 310/14, folder 10, Caskey to Morgan, May 27, 1956

The School’s good name was at risk: “… unless the bronze is returned promptly and gracefully, the good name of American archaeologists in Greece, and so of the School, is going to suffer a sharp blow. The French acted just right, asking no credit for returning the bronze that had been stolen (by others, of course) from Samos; and they received a lot of credit and good will from the Greek Ministry, and archaeologists. By contrast, we should look worse than Elgin,” concluded Caskey.

But what was the apple of discord? The only bronze figure that the Met acquired in 1955 was a small Hellenistic statuette of a rider wearing an elephant cap, and this seemed to have originated from Egypt. It does not seem that this was the figure that Greece wanted back and the Met refused to return. I have not been able to solve the riddle of the bronze figure. It also appears that the issue had not been resolved by April 1957, when Caskey, in another letter to Morgan, confessed that “just now I have had to report failure in my attempt to intercede in the matter of the missing work of art, about which you know, and this news of American irresponsibility [Caskey must be referring to the Met] made a really dismal impression on my Greek colleagues” (AdmRec 318/6, folder 2, April 18, 1957).

Afterthoughts

Although seemingly unrelated, the two cases point to the widening gap between art historians staffing American museums and field archaeologists, such as Caskey and Morgan, working in Greece in the 1950s. The former still operated under 19th century colonial terms, while the latter, especially Caskey, understood that following WW II there was a new world order in Greece to be taken into account and respected, despite his father having been Curator of Classical Art at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Although even he occasionally found the situation frustrating, he observed that both leftist archaeologists such as Meliades and conservatives such as Marinatos were justified in their belief that the foreign schools continued to be unreasonably critical of the work of their Greek colleagues.

It is of course easy enough for the [foreign] schools to criticize the Greek service in turn and point out its weaknesses, as well as the good that the foreigners do for Greece. But ultimately the Greeks are right; this is their country and they must make their own decisions.

Caskey confided to Morgan in late 1956 (AdmRec 318/6, folder 1, December 29, 1956)

As for stolen antiquities, such as the Hermes head from the Agora, the more publicity they receive the better it is. It is unclear how widely news of this loss circulated in 1955. Besides the short note in the London Times, I could not find a single reference in the newspapers.com database. The first time that a photo of the Hermes’ head appeared in a scholarly publication was in 1986 (Harrison 1986). Even if some of the large American museums were aware of its theft in the late 1950s, it is almost certain that, as curatorial staff retired or died (and with them institutional memory), the Hermes head moved from the top of the museums’ “hot list” to the bottom, when its photo was transferred to some institutional archive as an inactive record. It is laudable that the authors of the recent Hesperia article flagged its lost status several times in their essay. It remains out there somewhere, waiting to be repatriated to Greece.

References

Chatzi, G. (ed.) 2018. Γιάννης Μηλιάδης. Γράμματα στην Έλλη. Αλληολγραφία με την Έλλη Λαμπρίδη 1915-1937, Athens.

Harrison, E.B. 1986. “The Classical High-Relief Frieze from the Athenian Agora,” in Archaische und klassische griechische Plastik. Akten des internationalen Kolloquiums vom 22.–25. April 1985 in Athen 2: Klassische griechische Plastik, ed. H. Kyrieleis, Mainz, pp. 109–117.

Stewart, A., E. Driscoll, S. Estrin, N.J. Gleason, E. Lawrence, R. Levitan, S. Lloyd-Knauf, K. Turbeville, 2019. “Classical Sculpture from the Athenian Agora, Part 2: The Friezes of the Temple of Ares (Temple of Athena Pallenis),” Hesperia 88:4, pp. 625-705.