Celebrating Christmas and New Year’s in Athens, 1895-96: From the Letters of Nellie Reed, Student of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

Posted: December 31, 2024 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Greek Folk Art, History of Archaeology, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism, Uncategorized, Women's Studies | Tags: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Benjamin Ide Wheeler, Charles Edward Prior Merlin, Eben Alexander, Merlin House, Nellie Marie Reed, photography, Wilhelm Wilberg 8 Comments

“The American in Athens at Christmas time has a distinct advantage over the rest of mankind for each of his holidays is multiplied by two. He must of course celebrate the day the dear ones at home are enjoying and he is equally desirous of helping the Greeks in their festivities. The heading of his letter, Dec. 25, is contradicted by the postmark Dec. 13, much to his confusion until he finds that in Greece Father Time lags twelve days behind his record in other lands. But one is inclined to doubt even that date, so different is the approach of the sacred festival. Windows flung wide open admit the warm southern sunshine. A walk along the streets is rewarded by glimpses into gardens full of orange trees hung with golden fruit and rose trees covered with fragrant blossoms,” wrote Nellie Marie Reed (1872-1957) sometime in early 1896, after having spent a year at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or the School hereafter).

She was referring to Greece following the old (Julian) calendar, as did other eastern Orthodox countries in the 19th century. Christmas was celebrated on January 6 and New Year’s on January 13. The Gregorian calendar was adopted in Greece only in 1923. (See “An Odd Christmas” or the “Christmasless Year of 1923” in Greece .)

A graduate of Cornell University, Nellie attended the School in 1895-1896. We are fortunate to have in the School’s Archives the letters she sent to her family because they contain valuable information about her Greek experience. They were my main source of information for an essay exploring the close relations between the American School and the German Archaeological Institute in the late 19th century (On the Trail of the “German Model”: ASCSA and DAI, 1881-1918). Without her letters we would not have known that these relations were not limited to an official level but extended to informal, social gatherings between members of the two schools (the so-called “Kneipe” evenings); members of the Austrian Archaeological Station (not yet an Institute) were also part of these meetings.

Do I Really Want to Be an Archaeologist?

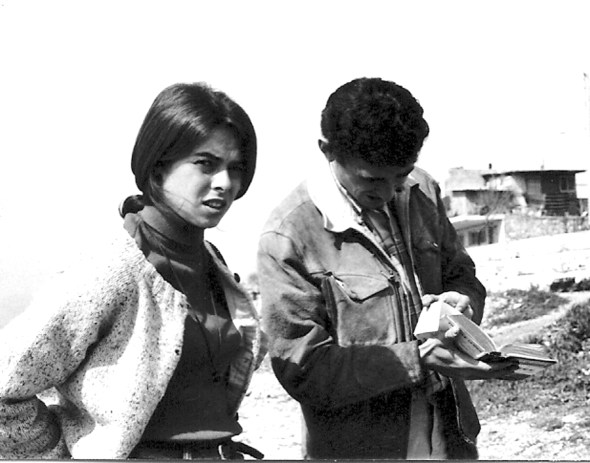

Posted: July 7, 2024 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Book Reviews, History of Archaeology, Mediterranean Studies, Modern Greek History, Philhellenism, Uncategorized, Women's Studies | Tags: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Archaeology, Athens, College Year in Athens, Eugene Vanderpool, Franchthi Cave, greece, History, Karen D. Vitelli, Porto Cheli Project, travel 13 CommentsThe first time I heard her name was in 1986 at Tsoungiza, Nemea. I had just been awarded a Fulbright fellowship to go to Bryn Mawr College for graduate school. James (Jim) C. Wright, one of the cο-directors of the Nemea Valley Project and a Fulbright fellow himself extended an invitation to me, Alexandra (Ada) Kalogirou and Maria Georgopoulou, the other two Greek Fulbrighters, to join the excavation, as a way of becoming familiar with the American way of life and education system. Ada was going to go to Indiana University to study Greek prehistory with Thomas W. Jacobsen (1935-2017) and Karen D. Vitelli (1944-2023).

I must have heard about Vitelli on and off over the next 10-15 years, but I never met her in person. I didn’t even know what she looked like. Then, in 2010, as I was preparing an exhibition to celebrate the 130th anniversary of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (the School, hereafter), I sent an email to various people asking for photos from the time they were students at the School. Stephen (Steve) G. Miller, former director of the School and a student at the School in the late 1960’s, sent me a few. One of the photos showed a tall, slim, dark-haired woman, who made an indelible impression on me. Several years later (2013), Kaddee (as she was known to nearly everyone) appeared at Mochlos together with her friend, archaeologist Catherine Perlès, at a wedding party for Tristan (Stringy) Carter, as guests of Tom Strasser, her former student. (By then Vitelli was Professor Emerita of Archaeology and Anthropology from Indiana University, Bloomington.) That was the first and last time I saw her in person.

On the Trail of the “German Model”: ASCSA and DAI, 1881-1918

Posted: August 10, 2020 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, History of Archaeology, Women's Studies | Tags: Adolf Wilhelm, American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Eugene P. Andrews, Georg Karo, German Archaeological Institute Athens, Germanophilia, Nellie M. Reed, Ruth Emerson Fletcher, Theodore W. Heermance, Wilhelm Dörpfeld 14 CommentsFounded in 1881, the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (hereafter ASCSA or the School) was the third foreign archaeological school to be established in Greece and followed the French and German models. For the first thirty years, the activities of the American School were closely intertwined with those of the German Archaeological Institute at Athens (DAI or German Institute hereafter) and the Austrian Archaeological Institute of Athens (Austrian Institute or Station hereafter).

Eloquent testimony to their informal relationship is found in the ASCSA Annual Reports (AR) from 1887 onwards, where the directors of the American School repeatedly extended their profound gratitude to Wilhelm Dӧrpfeld, Director of the German Institute (1887-1912), Paul Wolters, Second Secretary of the German Institute (1887-1900), and Adolf Wilhelm, Secretary of the Austrian Institute (1898-1905), for allowing American students to attend their weekly seminars and archaeological excursions. Only occasionally, would the ASCSA similarly express its gratitude to a French or British colleague. In fact, the ASCSA relied so heavily on the German Institute that it delayed developing an independent academic program of its own until Dӧrpfeld stopped offering his lectures and tours in 1908.

In order to reconstruct the early decades of the School’s history and its relationship to the German Institute, in addition to the Annual Reports, I have also relied on a second type of primary source: personal correspondence and diaries. Both are rare, however. Unlike official documents that have a greater chance of survival (sometimes in more than one copy) the preservation of family correspondence is a matter of luck. Of the 200 men and women who attended the School’s academic program from 1881 to 1918, the outgoing letters of fewer than a dozen members have survived, and of those only the letters of few have found their way back to the School’s Archives.

By nature, each type of source provides the researcher with different kinds of information, even if both sources refer to the same people or events. Official reports are formal and, to a certain extent, sanitized documents that deliver the governing body’s mindset. I, personally, find private correspondence a more insightful source, although it can be subjective and overstated; nevertheless, it is the best thing that a historian has at his/her disposal for reconstructing the past because its testimonies offer contemporary perspectives. At a time when cell phones, text messages, and social media were not available, a letter was the only way for reporting one’s activities and also for expressing one’s feelings. Glimpses, for example, at the private correspondence of Nellie M. Reed, student of the School in 1895-1896, reveal a continuous stream of informal American-German gatherings during that year, otherwise undocumented in the Annual Reports.

In 2016, I was invited to participate in a conference that explored the early history of the German Archaeological Institute at Athens. I used that event as an opportunity to study and re-write the “German chapter” in the history of the American School.[1] The narrative explores the catalysts that brought these two groups together and asks: Was it simply the vibrant and charismatic personality of Dӧrpfeld, who for three decades dominated the archaeological community of Athens, that was responsible for the rapprochement of the two institutions in the closing decades of the 19th century, or did the School’s close ties with the German and Austrian institutes reflect a larger educational trend that prevailed in American academic circles in the second half of the 19th century?

Forgotten Friend of Skyros: Hazel Dorothy Hansen (Part I)

Posted: April 19, 2020 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, Classics, Greek Folklore, History of Archaeology, Women's Studies | Tags: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, David M. Robinson, Dorothy Burr Thompson, George Mylonas, Hazel D. Hansen, Natalie Murray Gifford, Stanford University 12 Comments“Her main contribution was not destined to be in the field of excavation, but in discovering in dark cellars a good number of broken vases still covered with earth, discovered by others over the years in the island of Skyros. There she collected, cleaned, patched, and provided with a shelter transforming into a small Museum a room in the City Hall of Skyros. For this service to archaeology and the island she was made Honorary Citizen of Skyros,” wrote archaeologist George Mylonas about Hazel Hansen in early 1963, a few months after her death, in the Annual Report of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA or the School hereafter).

I asked several archaeologists of my generation and slightly older if her name or her association with the island of Skyros rang a bell. It did not, although she was known well enough in Greece, for her death to be noted at length in Kathimerini (December 22, 1962), one of the most respected Greek newspapers. «Ηγγέλθη χθες στην Αθήνα ο θάνατος της φιλέλληνος αρχαιολόγου καθηγητρίας του Πανεπιστημίου Στάνφορδ, Χέιζελ Χάνσεν, η οποία είναι ιδιαιτέρως γνωστή δια το σύγγραμμά της περί του αρχαιοτέρου πολιτισμού της Θεσσαλίας…”. In addition to her work in Thessaly and Skyros, the note referred to her participation in the excavations at Olynthus and on the North Slope of the Acropolis. The author of Hansen’s Greek obituary knew her well and wanted to capture the accomplishments of a friend and able colleague. It must have been (again) George Mylonas, whose friendship with Hazel started in the 1920s when they were both at the American School.

Hazel D. Hansen, 1923. ASCSA Archives, Carl W. Blegen Papers.

“From ‘Warriors for the Fatherland’ to ‘Politics of Volunteerism’: Challenging the Institutional Habitus of American Archaeology in Greece.

Posted: February 1, 2020 Filed under: Archaeology, Archival Research, Biography, History of Archaeology, Intellectual HIstory, Mediterranean Studies, Philhellenism | Tags: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Archaeological Institute of America, Colophon Excavations, Edward Capps, Hesperia, Jack L. Davis 3 CommentsDisciplinary history is not a miraculous form of auto-analysis which straightens out the hidden quirks of communities of scholars simply by airing them publicly. But it does force us to face the fact that our academic practices are historically constituted, and like all else, are bound to change.

Ian Morris, Archaeology as Cultural History, London 2000, p. 37.

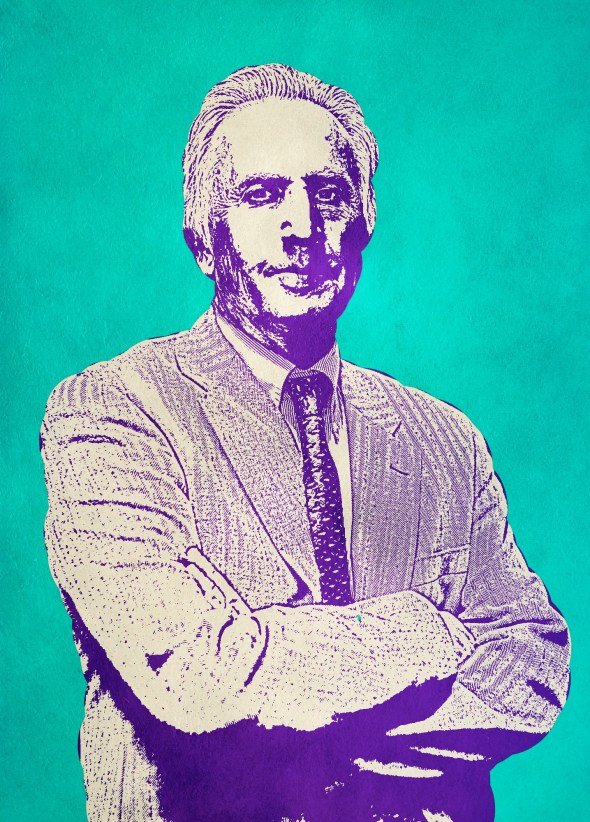

Jack L. Davis. Created by Blank Project Design, 2020.

“Archives may be even more important than our publications” said Jack L. Davis in his acceptance speech on January 4, 2020, at the Annual Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America (AIA) in Washington D.C. Recognizing his outstanding career in Greek archaeology, the AIA awarded Davis, a professor of Classics at the University of Cincinnati and former Director of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (and a frequent contributor to this blog), the Gold Medal Award for Distinguished Archaeological Achievement. Earlier that day, in a symposium held in his honor, eight speakers highlighted Davis’s contributions to the field. Honored to be one of them, I presented a paper about a lesser known aspect of his career: his scholarship concerning the history and development of American Archaeology in Greece. An updated version of my paper follows below.

“Warriors for the Fatherland” (2000)

Jack Davis made his debut as an intellectual historian and historiographer in 2000 when he published “Warriors for the Fatherland: National Consciousness and Archaeology in ‘Barbarian’ Epirus and ‘Verdant’ Ionia, 1912-1922” (Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 13:1, 2000, pp. 76-98). Following “Warriors,” he published more than twenty essays of historiographical content in journals, collected volumes, and online platforms. Today I have chosen to review the ones that, in my opinion, offered counter-narratives challenging the institutional habitus of American archaeology in Greece. Read the rest of this entry »